Dracula by Bram Stoker Summary, Characters and Themes

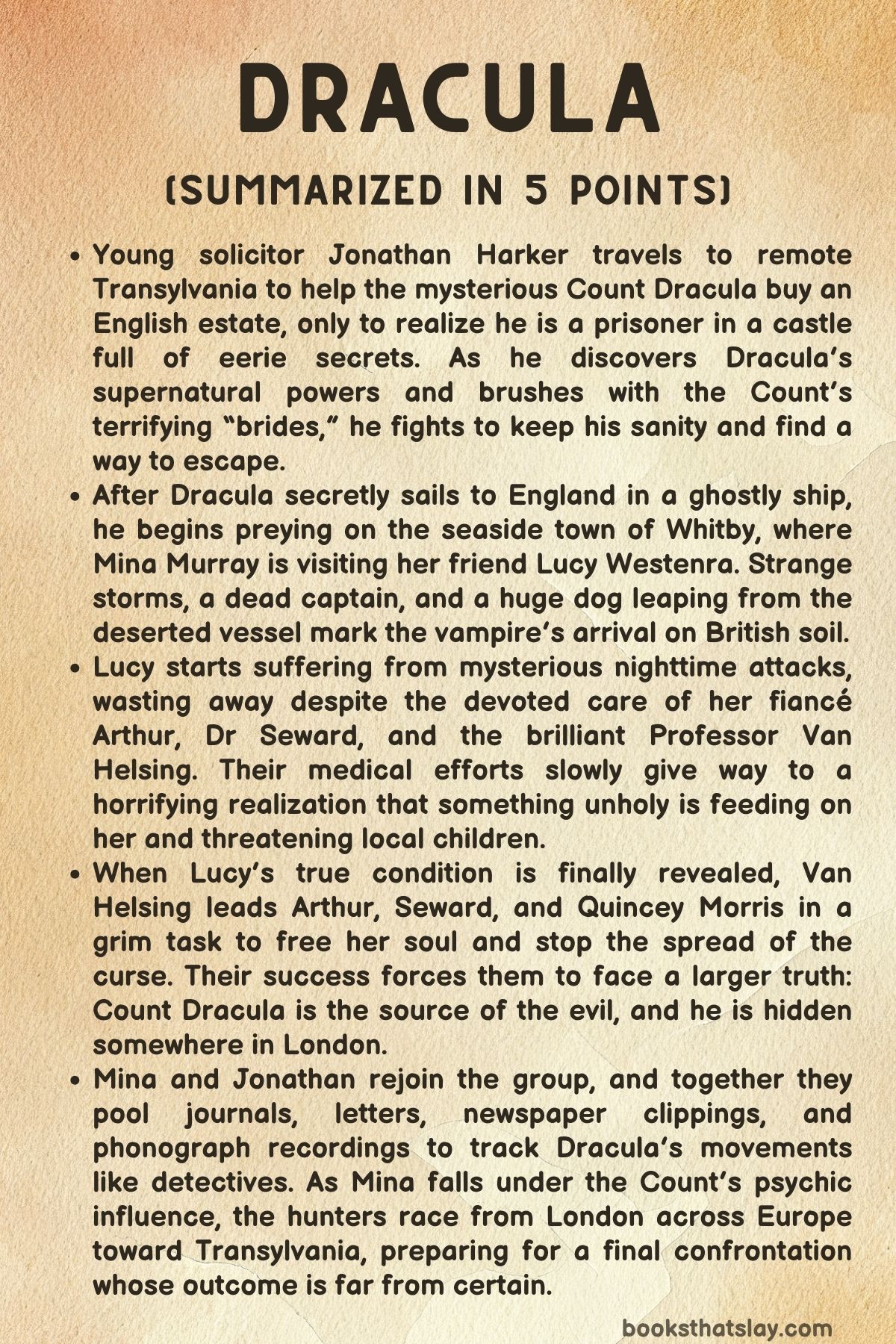

Dracula by Bram Stoker is a Gothic horror novel told through diaries, letters, newspaper clippings, and official documents. This collage of voices follows a group of ordinary people who slowly uncover an ancient, supernatural evil and decide to fight it with courage, faith, and reason.

At its heart, Dracula is about invasion: a foreign, centuries-old vampire comes to modern London, feeding on its people and corrupting its most innocent. Against him stand a devoted young couple, their friends, and a brilliant professor, who turn careful record-keeping into both a weapon and a shield.

Summary

The story opens with Jonathan Harker, a young English solicitor, travelling to remote Transylvania to help a mysterious nobleman, Count Dracula, purchase property in England. As Jonathan moves eastward, locals shower him with charms against evil and whisper of werewolves, witches, and vampires.

At the Borgo Pass he is collected by a terrifying coachman who controls wolves with a gesture and drives him through storm and snow to a ruined castle perched high in the Carpathians.

The host who welcomes him is Count Dracula, an unnaturally strong old man with cold hands, sharp teeth, and no servants. Jonathan soon realizes the Count never eats, appears only at night, and casts no reflection in a mirror.

When a shaving cut makes Jonathan bleed, Dracula reacts with animal hunger, then recoils in fury from the crucifix on Jonathan’s neck. Exploring the castle, Jonathan sees the Count crawl down the walls like a lizard and discovers that he himself is a prisoner.

One night, after ignoring a warning to sleep only in his own room, Jonathan encounters three unnervingly beautiful vampire women who try to drink his blood. Dracula interrupts in rage, claiming Jonathan as his own prey and giving the women a bag containing a child instead.

Forced to write false letters dated ahead to cover his disappearance, Jonathan finally finds the Count lying in a box of earth in a castle crypt, motionless but warm and flushed. Soon carts arrive to carry away fifty such boxes.

Jonathan resolves to risk any escape rather than be left to the vampire women.

The scene shifts to England, where Jonathan’s fiancée Mina Murray exchanges letters with her friend Lucy Westenra. Lucy, staying by the sea at Whitby, receives three marriage proposals in one day—from Dr John Seward, American adventurer Quincey Morris, and Arthur Holmwood, whom she loves and accepts.

Dr Seward, heartbroken, throws himself into his work at a nearby lunatic asylum, where he studies a patient named Renfield, obsessed with consuming smaller lives—flies, spiders, birds—to gain vitality.

Mina joins Lucy in Whitby. A violent storm drives a Russian ship into the harbour; its crew are dead, and a huge dog leaps ashore and vanishes toward the graveyard.

Soon after, Lucy begins to sleepwalk and grow strangely weak. Each night Mina finds her out on the cliff-top, pale, with tiny wounds in her throat, and hears a mysterious flapping figure in the dark.

Lucy’s health declines, and Dr Seward calls in his old teacher, Professor Abraham Van Helsing.

Van Helsing suspects something unnatural. He uses garlic flowers and constant watch to protect Lucy, but his precautions are disrupted by well-meaning relatives and his own absence.

Several men—Seward, Arthur, and Quincey—give Lucy blood transfusions, yet her strength ebbs. Eventually, after a final attack, she dies seemingly peaceful.

Soon reports surface of a “Bloofer Lady” luring children in Hampstead, who are later found with bites on their throats.

Convinced Lucy has become a vampire, Van Helsing leads Seward, Arthur, and Quincey to her tomb. At night they see her walking with a child in her arms, face sensual and cruel.

In daylight they find her body in the coffin, unnaturally preserved and beautiful, with sharp teeth and bloodstained lips. Van Helsing explains the nature of the Un-Dead and persuades Arthur to free Lucy’s soul by driving a stake through her heart.

After the horrific act, her face returns to its former sweetness. Van Helsing and Seward complete the rite by beheading her and filling her mouth with garlic.

Meanwhile, Jonathan, who has escaped to Budapest, returns to England and marries Mina. Van Helsing gathers everyone and shares their diaries, letters, and notes, which Mina carefully types and organizes.

Jonathan has recognized Dracula in London, now a younger, vigorous man buying houses full of earth boxes. By collating all records, the group realize that the Count travelled on the doomed ship to Whitby, has been using the boxes of Transylvanian soil as resting places, and was Lucy’s attacker.

They locate and sanctify most of Dracula’s lairs around London, forcing him to flee from safe house to safe house. Renfield, who has sensed the Count’s presence and alternates between worship, terror, and rebellion, is fatally injured after refusing Dracula entry.

During a final assault on the asylum, Dracula forces Mina to drink his blood, creating a psychic link and threatening to turn her into a vampire. This horror steels the group’s resolve.

Using hypnotism at dawn and sunset, Van Helsing uses Mina’s connection to track the Count’s movements.

With his London refuges disrupted, Dracula escapes by ship back toward his castle, transporting his last box of earth. The hunters pursue.

Mina’s hypnotic visions of water and creaking wood reveal the Count’s route. In Eastern Europe the party splits: Arthur and Jonathan follow the river by steam launch, Quincey and Seward ride along the banks with horses and rifles, while Van Helsing takes Mina by carriage toward Castle Dracula to purify his remaining lairs.

Near the castle, Mina’s condition worsens, and hypnotism fails. Van Helsing protects her within a circle of holy tokens that she cannot cross, revealing her partial contamination yet preserved soul.

He enters the castle alone, discovers Dracula’s three vampire women in their tombs, and destroys them with stake and knife, then seals the Count’s chapel so he can never again rest there.

Out on the snowy plain, the Szgany gypsies hauling Dracula’s box by wagon are intercepted by the others. Wolves gather as the sun sinks and the hunters close in from different directions.

In the brief remaining daylight, Jonathan and Quincey fight through the defenders, drag the heavy box down, and break it open. Inside lies Dracula, eyes kindling with anticipatory triumph.

Jonathan slashes the Count’s throat, and Quincey drives a knife into his heart. The vampire’s body crumbles to dust, and at that same moment the mark on Mina’s forehead vanishes, showing the curse is broken.

Quincey, mortally wounded in the fight, dies surrounded by his friends, content that their mission has succeeded. In an epilogue set years later, Jonathan and Mina revisit Transylvania with their young son, named Quincey in honour of their fallen companion, and reflect on the strange chain of documents and memories that allowed them to defeat the ancient evil of Dracula.

Characters

Jonathan Harker

Jonathan is our first window into the world of Dracula, and he begins as the model Victorian professional: dutiful, rational, and slightly proud of his efficiency and modern training. On his way to Transylvania he treats the strange food, customs, and superstitions of the locals with amused curiosity, like a tourist confident in Western progress.

That makes his psychological journey in the castle especially striking: as he realizes that the doors are all locked and that he is effectively a prisoner of an inhuman host, his lawyerly rationalism is stretched to the breaking point. The moment he sees Dracula crawl down the castle wall like a lizard marks a turning point, when fear finally overcomes his habit of explaining everything away.

Yet Jonathan never fully collaps; even in terror he keeps writing his diary as “bare fact” to hold onto his sanity, and he repeatedly risks his life, climbing along sheer walls and confronting Dracula in his box, instead of submitting passively. Later in England, his mind is so shaken that he doubts his own memories, which makes Van Helsing’s belief in his journal a kind of emotional rescue.

Once his experience is validated and he knows he is not mad, Jonathan’s courage hardens into a calm, almost grim resolve. By the final pursuit in Transylvania he has grown from naïve clerk to determined vampire hunter, capable of leaping onto a moving cart and cutting the Count’s throat without hesitation.

His character arc shows how terror, love for Mina, and a sense of moral duty can transform an ordinary man into a heroic one, but always with that core of decency and conscientiousness we saw from the beginning.

Count Dracula

Dracula himself is both ancient warlord and cold strategist, a figure who combines aristocratic pride with predatory cunning. In his castle he initially presents himself as a courteous, if unsettling, host who speaks careful English and insists on carrying Jonathan’s bags, but small details immediately suggest something wrong: he never eats, his hand is ice-cold, and there are no servants.

The politeness is revealed as a mask for control. He manipulates Jonathan’s movements, forces him to write misleading letters, intercepts and burns his private correspondence, and systematically strips him of clothes, papers, and even identity so that he can later impersonate him.

Dracula’s relationship with his ancestral land is fierce and almost patriotic: he boasts of the Szekely and the Draculas as frontier defenders and revels in histories of blood and conquest. That pride feeds directly into his plan to colonize England, which he has studied through books until he “loves” it as a field of opportunity.

His supernatural abilities – command of wolves, control over weather and fog, the ability to crawl down walls, survive in a trance-like half-life in boxes of earth, and maintain psychic connections to victims – make him terrifying, but his so-called “child-brain” is just as important. He is clever but repetitive, relying on the same tactics of secrecy, control of transport, and exploitation of legal and social blind spots.

Emotionally, Dracula is strangely underdeveloped: when the three vampire women accuse him of never having loved, his furious denial feels defensive but unconvincing. His most genuine reactions are hunger, wrath, and a kind of wounded pride when his plans are thwarted.

At the very end, when his body dissolves and his face briefly looks peaceful, the novel offers a fleeting suggestion that even this monstrous figure was once human, but it never redeems him; he remains the central embodiment of parasitic, corrupting power that must be hunted down and destroyed.

Mina Murray / Mina Harker

Mina is the moral and intellectual heart of Dracula. Outwardly she fits the ideal of the devoted Victorian wife, constantly described by others as sweet, gentle, and “truer than man” in her loyalty and compassion.

Yet the narrative repeatedly shows that she is also the group’s most capable organizer and analyst. Her shorthand skills, typewriting, and methodical arrangement of letters, diaries, and newspaper articles turn scattered, subjective experiences into a coherent case file on Dracula.

Van Helsing’s delighted reaction to her typewritten diary – calling it “sunshine” that illuminates their confusion – acknowledges that without her, the men’s knowledge would remain fragmented. She is also emotionally perceptive: she consoles Seward, supports Jonathan through his trauma, and quietly takes on painful tasks, such as listening to Seward’s phonograph diary about Lucy’s death and then typing it to spare him repeated grief.

Mina’s own suffering, once Dracula forces her to drink his blood and marks her with the scar on her forehead, deepens her role. She becomes both victim and weapon; the group tries to use Van Helsing’s hypnotism on her to track Dracula’s movements, even while knowing that the connection is slowly killing her.

Mina is painfully aware of this double position. She insists that all records, including her own, be used to defeat the monster, even if that means exposing her shame and fear.

Near the end, when she cannot step out of the protective circle of holy wafers, the horror of her partial contamination is set against Van Helsing’s insistence that her soul remains pure. The disappearance of the scar at the moment of Dracula’s destruction confirms her spiritual innocence and justifies the men’s faith in her.

Through Mina, the novel suggests that courage, intelligence, and selfless love are not exclusively masculine virtues and that true heroism often lies in persistence, empathy, and clear thinking rather than brute force.

Lucy Westenra

Lucy represents both vulnerability and the seductive danger of vampirism in Dracula. At first she is charming, affectionate, and slightly playful, writing to Mina about receiving three proposals in one day with a mixture of guilt and girlish delight.

She is sincerely in love with Arthur Holmwood, and nothing in her character suggests malice or instability. Yet she is also physically and psychologically more porous than Mina: a habitual sleepwalker, easily influenced by the environment, spending long evenings in Whitby’s churchyard under the shadow of the ruined abbey.

These traits make her an ideal target for Dracula’s predation. The sequence of her illness, with unexplained blood loss, strange punctures in her throat, and cycles of apparent recovery followed by relapses, shows how thoroughly she is being drained, not only physically but socially and spiritually.

After her death and transformation into the “Bloofur Lady” who preys on children, Lucy becomes a dark mirror of herself. The maternal, affectionate young woman is twisted into a voluptuous, cruel figure who lures a child and then tries to seduce Arthur with perverse intimacy, calling him her husband and inviting him into her arms.

The men’s horror is sharpened because they remember her innocence, and Arthur’s agony at having to drive a stake through her heart embodies the cruel necessity of confronting evil even when it wears a beloved face. When Lucy’s features soften after the staking and she looks once more like the “sweet” woman they had known, the narrative insists that the vampiric Lucy and the human Lucy are morally distinct.

Her arc thus dramatizes the consequences of Dracula’s intrusion into England: he turns a model young woman into a predator on the most vulnerable, and only violent, quasi-ritual “mutilation” can restore her to peace.

Professor Abraham Van Helsing

Van Helsing is the intellectual and spiritual leader of the anti-Dracula campaign, a man of vast learning, deep feeling, and occasionally maddening secrecy. Trained in medicine and science but also open to folklore, religion, and the supernatural, he serves as a bridge between modern rationalism and the ancient beliefs necessary to understand vampires.

His relationship with Seward reveals a mentor who deliberately challenges his pupil’s scepticism, citing examples like hypnotism, monstrous animals, and long-lived creatures to widen the boundaries of what science should consider. Van Helsing’s emotional range is wide: he weeps openly over Lucy, blessing her and Arthur; he exults with almost childlike delight when Mina’s documents clarify a puzzle; and he expresses fierce moral conviction when insisting that the Un-Dead must be destroyed to free their souls and protect the living.

Yet he can also be manipulative in a paternalistic way, withholding information “for their own good” and orchestrating events so that Arthur will accept the necessity of staking Lucy by seeing her vampire form with his own eyes. His determination at Lucy’s tomb, directing the gruesome work of staking, decapitation, and filling the mouth with garlic, shows a man capable of doing terrible things in the service of a higher good.

With Mina, he becomes almost chivalric, calling her “Madam Mina,” praising her courage and intelligence, and feeling profound gratitude for her records. In the final journey back to Transylvania, he plays the role of both scholar and warrior-priest: arranging timetables, explaining Dracula’s “child-brain,” and personally entering the castle to sanctify the lairs and destroy the three vampire women.

Van Helsing embodies the novel’s ideal of a modern hero who uses both science and faith, and who accepts that fighting a supernatural evil requires ugly, bloody acts carried out with reverence and compassion.

Dr John Seward

Seward is a complex figure, caught between scientific detachment and emotional turmoil. As a doctor and head of a lunatic asylum, he prides himself on classification and observation, which is evident in his detailed notes on Renfield’s behaviour.

His initial response to mysteries is always to seek rational explanations, and he clings to this even when confronted with increasingly bizarre evidence. At the same time, Seward is personally wounded: his love for Lucy and her rejection in favour of Arthur leave him heartbroken, and he tries to sublimate that pain by throwing himself into work.

This emotional wound makes Lucy’s illness and death even more devastating for him, and his phonograph diary becomes both scientific record and confession of grief. When Van Helsing first suggests that Lucy has become a vampire and that she is responsible for the children’s injuries, Seward reacts with anger and disbelief, protesting that such notions are “outré.” His gradual acceptance of the supernatural is one of the novel’s key psychological transformations.

Once convinced, he commits himself wholeheartedly to the hunt, using his medical expertise to assist Van Helsing, his asylum as a base of operations, and his diary as part of the shared archive. Seward’s interactions with Mina further reveal his decency: he worries about subjecting her to the horrors of Lucy’s fate, but he respects her insistence on knowing everything and is moved by her courage in typing out his most painful memories.

In the final chase, Seward rides with Quincey along the river, enduring physical hardship alongside emotional scars. He never becomes the central hero, but as a loyal, intelligent, and increasingly open-minded companion, he represents the best of late Victorian scientific humanity learning to face realities beyond its old categories.

Arthur Holmwood / Lord Godalming

Arthur begins as the handsome, wealthy aristocrat whose proposal Lucy accepts, and his role at first appears almost decorative compared to Seward’s scientific mind or Quincey’s frontier bravado. Yet as the story unfolds, Arthur becomes a symbol of emotional suffering, duty, and the transformation of grief into resolve.

Lucy’s illness affects him deeply; he oscillates between hope and helplessness, trusting the doctors but unable to comprehend the real cause. After her death he is left in a state of raw grief, and Van Helsing’s request that he enter the tomb and countenance the “mutilation” of her body strikes him as almost sacrilegious.

The scene in which Arthur must drive the stake through Lucy’s heart is one of the most emotionally charged in Dracula. He trembles and turns pale, but accepts the task as the one who loved her most.

The act itself, the horror of the body’s convulsions and scream, followed by the transformation of her face back to sweetness, both traumatizes and heals him. It allows him to believe that her true self has been saved.

After this, Arthur, now Lord Godalming following his father’s death, brings his social status, wealth, and quiet bravery to the group. He finances parts of their operations, uses his title when helpful, and joins the final pursuit without hesitation.

Although less vocal than others, he stands as a figure of noble suffering and steady loyalty, a man who has confronted the worst imaginable act and still chooses to go on fighting.

Quincey Morris

Quincey, the Texan adventurer, adds an element of rugged individuality and cheerful courage to the otherwise very English ensemble. He is energetic, straightforward, and generous, taking Lucy’s refusal with good grace and offering Arthur and Seward lifelong friendship instead of resentment.

His skill with weapons and horses makes him especially valuable during the more physical parts of the hunt, such as riding along the river with Seward to track the box of earth. Emotionally, Quincey often plays the role of morale booster, refusing self-pity and lightly masking his own disappointments.

His American background suggests a different, more frontier-facing kind of masculinity, one that is comfortable with danger and used to improvisation. This culminates in the final battle at the wagon: Quincey fights through the gypsy ring, suffers a mortal wound, and still helps Jonathan open the box and stab Dracula.

His death scene is poignant because it is both tragic and serene. He dies outdoors, under the last rays of the sun, satisfied that the mission has succeeded and pointing to Mina’s healed forehead as proof that their sacrifice was not in vain.

Quincey’s willingness to give his life for friends and for a woman who could never be his makes him an idealized chivalric hero in a Western key, and his memory lingers as part of the price paid to defeat the vampire.

Renfield

Renfield is one of the most disturbing and fascinating characters in Dracula, serving as a kind of dark echo of the Count’s philosophy. As Seward’s “zoophagous maniac,” he fixates on ingesting life in progressively larger forms: flies, spiders that eat the flies, then sparrows, which he ultimately consumes himself.

This grotesque chain is driven by a belief that life can be accumulated, stored, and used, which parallels Dracula’s parasitic immortality. Renfield’s apparent madness is not simply random; it has its own logic rooted in power and survival.

His behaviour shifts in tandem with Dracula’s presence and movements, making him a sort of barometer of the vampire’s influence. Unlike Dracula, however, Renfield is capable of remorse and moral struggle.

At key moments he seems to grasp the horror of what he is involved in and tries to warn the others, showing flashes of lucidity and compassion. His obsession with life turns into fear of his own damnation and of the suffering of others.

In some versions of the story, his attempt to resist Dracula has tragic consequences for him, underlining the difference between a human being ensnared by evil and the inhuman source of that evil. Renfield’s presence in the asylum also serves to highlight Seward’s initial limits: the doctor interprets his patient’s behaviour through the lens of pathology rather than supernatural influence, delaying recognition of the larger pattern.

As a character, Renfield sits uneasily between comic grotesque and tragic victim, illustrating how thin the line can be between rationality and madness, and how a human thirst for power can shade into monstrousness.

Mr Swales

Mr Swales is a minor but telling character in Dracula, grounding the Whitby scenes in local colour and scepticism. As an old sailor, he speaks bluntly and irreverently, mocking superstitions, poking fun at the false inscriptions on tombstones, and dismissing tales of ghosts.

His initial role is almost comic, a gruff contrast to the romantic setting of ruined abbey and cliff-top graveyard where Lucy and Mina talk. However, as the ominous storm approaches and the strange Russian ship draws near, Mr Swales’s tone shifts.

He grows sombre, speaks of his own nearness to death, and confesses a sense of doom in the wind. This change lends weight to the coming disaster, as if even the hardened sceptic can feel the approach of something beyond ordinary experience.

Mr Swales thus functions as a barometer of atmosphere and a bridge between everyday coastal life and the incursion of the supernatural. His arc from mockery to unease mirrors, on a small scale, the novel’s larger movement from rational dismissal of superstition to terrified belief.

The Szgany, Slovaks, and Other Human Agents

The Szgany gypsies, Slovak wagoners, ship’s crew of the Czarina Catherine, and minor figures such as Immanuel Hildesheim and Petrof Skinsky collectively show how Dracula relies on human networks to extend his power. Many of these people do not understand the true nature of the cargo they transport; they are motivated by money, habit, or fear.

The Szgany who serve Dracula at the castle and later guard his box near the end demonstrate fierce loyalty to their employer, fighting with knives to protect the cart even against armed gentlemen. Hildesheim and Skinsky in Galatz appear as familiar shady intermediaries, used to handling suspicious goods and operating on the fringes of legality.

The Czarina Catherine’s captain is another telling figure: he ties himself to the wheel with a rosary in hand, symbolizing both professional duty and religious desperation as he steers a cursed ship through storm and fog. These characters do not receive long psychological development, but their actions show that supernatural evil rarely operates in isolation.

It uses existing social structures – shipping routes, peasant labour, grey-market agents – to move across borders and hide in plain sight. In this way, the novel hints that everyday complicity, ignorance, or moral indifference in human beings can help monstrous forces thrive.

Themes

Fear, Imprisonment, and Psychological Terror

Jonathan’s stay in the Carpathian castle turns the idea of imprisonment into a sustained torment that shapes the whole of Dracula. At first he believes he is an honored guest, treated to rich food and courteous conversation, but little details unsettle him: the absence of servants, the locked doors, the sheer drops under every window, and the fact that his host never seems to eat.

The shift from polite visit to captivity happens quietly, almost bureaucratically, as Jonathan notices that every possible exit has been controlled. This gradual realization produces a specific kind of fear: not sudden shocks, but the dawning understanding that he has been enclosed inside someone else’s will.

When he sees the Count crawling down the wall like a lizard, the castle stops being just a remote building and becomes a kind of living trap, a place that obeys the vampire’s unnatural laws rather than human ones.

That sense of entrapment spreads beyond Jonathan. The gypsies who serve the Count do so within a network of loyalty and intimidation that makes them extensions of his power, turning the landscape around the castle into a wider prison yard.

In England, the same dynamic reappears in a modern setting: Lucy sleepwalks, children are lured away, and later Mina is psychically linked to the vampire. None of them are chained in a literal sense, yet their bodies and wills are overridden.

Terror arises not just from physical danger but from the feeling that one’s mind, one’s movements, even one’s letters home can be manipulated. The fake letters Jonathan is forced to write, and the way Dracula intercepts and burns his private correspondence, show how thoroughly the Count controls communication as well as space.

By the end of the novel, the hunters’ pursuit of the box across land and water is shaped by the memory of that earlier confinement. Jonathan’s desperation to risk death rather than remain in the castle is echoed in the later decision to ride into snow, rapids, and ambushes rather than let Dracula slip away.

Fear has taught them that passivity means being caged. The final confrontation around the wagon is not simply a battle with a monster; it is a struggle to prevent the prison of the castle from expanding across continents and turning English streets, churches, and homes into new cells in Dracula’s domain.

Modernity, Science, and Ancient Superstition

The novel consistently stages encounters between modern methods and ancient beliefs, showing neither as sufficient by itself. Jonathan travels with railway timetables, legal documents, and guidebooks, bringing the mindset of a trained English professional into a region defined in his reading as backward and superstitious.

The peasants’ charms, crucifixes, and whispered words—“vampire,” “werewolf,” “Satan”—initially strike him as quaint or irrational. Yet once he sees Dracula’s reflection absent from the mirror and witnesses the Count crawling down the castle wall, he is forced to admit that the local folklore provides the only language that fits what he has observed.

His legal training and rational habits help him record events precisely, but they do not explain them.

In England, Dr Seward represents the medical and psychiatric world at its most self-confident. He has a phonograph diary, runs a modern asylum, and studies Renfield with clinical terminology such as “zoophagous maniac.” At first, he looks for a pathological explanation for everything, including Lucy’s symptoms and the children’s wounded throats.

Van Helsing, though also a scientist and physician, keeps one foot in a broader tradition that includes theology and folklore. His lectures to Seward about hypnotism, long-lived creatures, and unexplained phenomena are meant to stretch the younger man’s sense of what counts as “possible” within a scientific worldview.

The novel does not frame this as a simple victory of superstition over science; instead, it portrays an expanded science that makes room for realities that Victorian rationalism prefers to ignore.

The tools of modernity—typewriters, telegrams, phonographs, trains, and steam launches—become essential weapons once the characters accept the existence of the supernatural. Mina’s typewritten documents, the rapid exchange of telegrams tracing the Czarina Catherine, and the expert use of railway timetables show modern infrastructure working in tandem with consecrated wafers, crucifixes, and stakes.

Van Helsing sanctifies the castle’s lairs with holy objects, while the others rely on engines and schedules to intercept the box. Through this combination, Dracula suggests that modern progress is not meaningless, but dangerous when cut off from older forms of wisdom.

Scientific arrogance leaves gaps through which something like Dracula can enter; mature science, willing to admit what it cannot fully explain, becomes part of the resistance instead of part of the problem.

Gender, Sexuality, and the Threat of the “New” Woman

The women of Dracula expose Victorian anxieties about female desire, agency, and virtue. Jonathan’s encounter with the three vampire women is described through his own conflict between dread and a “wicked, burning” attraction.

The fair woman’s approach, with her lips on his throat and her slow enjoyment of the moment, reverses the usual dynamics of Victorian courtship: he becomes passive, she becomes the predator. The scene has the structure of seduction, but the object is not mutual pleasure or marriage; it is the draining of his blood and his transformation into prey.

That mixture of erotic suggestion and horror reflects a fear that female sexuality, freed from traditional restraints, could become consuming and destructive.

Lucy dramatizes this fear in a more socially acceptable form at first. Her three proposals in one day, and her light-hearted joking about how she wished she could marry all three men, hint at a woman whose charm and romantic imagination stretch the boundaries of conventional modesty.

Once she is bitten, her sleepwalking, night wanderings, and later her predatory visits to children show a darker version of that earlier openness. As a vampire she becomes voluptuous, cruel, and manipulative, trying to lure Arthur with the language of wifely intimacy while using a child as a discarded toy.

The transformation can be read as Victorian patriarchy’s nightmare: the loving fiancée turned into a figure of unrestrained appetite who threatens men and children alike. The violent “cure” for this is telling: Arthur must drive a stake through her heart, and Van Helsing must cut off her head and fill her mouth with garlic, literally stopping that dangerous mouth forever.

Only then is she allowed to appear once more as the sweet, chaste woman they remember.

Mina, by contrast, is praised for her intelligence and energy but constantly framed as “good” because she uses those qualities in service of men and moral order. She is the “train fiend,” the organizer of documents, the person who masters shorthand, typing, and research, yet she remains self-sacrificing and obedient.

Even when she insists that all records must be shared and that she should hear the painful details of Lucy’s end, she presents her determination as a wifely and friendly duty. The novel rewards her with survival and motherhood, but only after a period in which she becomes marked by Dracula and must be carefully protected.

Through these contrasting figures—vampire women, Lucy, and Mina—Dracula explores the possibilities of changing gender roles while reaffirming a conservative ideal of virtuous femininity that helps restore order once the threat has been destroyed.

Faith, Sacred Objects, and Spiritual Warfare

Religious symbols, especially Christian ones, are not decorative in Dracula; they operate as real forces within the story’s logic. The old woman at the inn who hangs a crucifix around Jonathan’s neck acts from simple piety and fear, yet that gesture repeatedly saves him.

Dracula’s violent recoil when his hand touches the crucifix after lunging at Jonathan’s bleeding throat signals that the battle is not only physical but spiritual. The peasants crossing themselves, the roadside shrines, and the captain of the doomed ship lashed to the wheel with a rosary and crucifix all point to a worldview in which evil is understood as more than a metaphor and must be resisted with more than courage.

Van Helsing’s methods intensify this spiritual dimension. He uses consecrated wafers to seal Lucy’s tomb, to bar the Un-Dead from their resting places, and later to protect Mina by drawing a circle she cannot cross.

That moment near the Borgo Pass, when Mina discovers she is unable to step outside the circle, is especially striking: she is in some sense already touched by vampirism, yet the holy boundary both prevents her from wandering into danger and confirms that her soul remains aligned with the sacred. The wafers and crucifixes work not because people believe in them but because, within the novel’s world, they participate in a larger divine order that opposes Dracula’s parasitic existence.

The act of destroying vampires is framed as a grim religious duty rather than simple monster-hunting. Van Helsing insists that Lucy’s staking and decapitation are necessary to free her soul from the curse of the Un-Dead, and Arthur’s final kiss on her now-restored face reads as a farewell ritual as much as a personal goodbye.

In the castle, Van Helsing’s solitary mission to stake the three vampire women and sanctify Dracula’s tomb echoes a priest cleansing a defiled temple. Even the final destruction of the Count, though carried out with knives rather than holy water, is described in terms of release: his face is momentarily peaceful as his body collapses to dust, as if the spiritual order has been restored by his annihilation.

The novel thus presents faith not simply as comfort or superstition, but as a structured set of practices that can counteract evil when combined with human resolve.

Information, Records, and Collective Intelligence

The epistolary form of Dracula is not just a stylistic choice; it expresses a theme about the power of information and organized record-keeping. Jonathan, Mina, Seward, Van Helsing, and others all keep journals, letters, telegrams, newspaper clippings, and phonograph recordings.

At first these are private or professional habits: Jonathan’s travel notes, Seward’s psychiatric observations, Mina’s personal diary. Once the nature of the threat becomes clearer, Mina recognizes that scattered accounts are not enough.

Her decision to type and collate everything into a coherent chronology transforms the group’s personal experiences into a shared resource. Facts that looked meaningless in isolation—Renfield’s patterns, shipping news, a report about children with throat wounds—turn into evidence once viewed side by side.

The Count understands this threat to his secrecy and repeatedly attacks the flow of information. He forces Jonathan to write misleading letters with future dates, tries to dictate what news reaches England about his guest, and destroys documents when he can.

His attempt to cut off Mina’s access to knowledge appears again in the later chapters, when he tries to control her through the psychic connection, prompting Van Helsing and the others to treat her both as a victim to protect and as a source of intelligence. Her hypnotic trances, describing sounds of water and creaking wood, give the hunters partial insight into the Count’s movements, while her analytical memoranda help them anticipate his likely route toward the Borgo Pass.

The group’s success by the end depends less on individual heroism than on a system of collection, verification, and strategic planning. Telegrams fly between ports, shipping agents are questioned, timetables are consulted, and multiple teams coordinate by land and river.

This suggests that, in a modern world, evil can move quickly using the same networks humans build—but it can also be tracked and opposed through disciplined information work. Mina’s typewriter and Seward’s phonograph stand alongside crucifixes and stakes as essential tools.

The novel therefore hints at an early form of collective intelligence: a community able to overcome a radically individual predator because it can share, preserve, and act on knowledge more effectively than he can conceal his trail.

Invasion, Empire, and the Foreign “Other”

Count Dracula’s journey from Transylvania to England gives the story an unmistakable pattern of invasion. Early on, Jonathan’s travel notes mark a border crossing from West to East, from familiar cities like Vienna into a region presented as wild, backward, and haunted by past wars.

The blue flames over buried treasure and the long history of conflict that Dracula recounts paint his homeland as a frontier saturated in blood. When he studies English law, customs, and language in his castle library, he is not simply pursuing curiosity; he is preparing a covert entry into the heart of a global imperial power.

His chosen property, an old estate next to a lunatic asylum and near multiple routes into London, becomes a base of operations inside Britain.

The pattern of his movements in England echoes the fears of a late nineteenth-century empire anxious about threats from the periphery. Dracula arrives as a “huge dog” leaping from a ship in a storm, dodging controls and paperwork.

The Russian schooner brings him under a foreign flag, without a surviving crew to explain what happened. Once ashore, he circulates at night, infiltrates homes, and preys on vulnerable bodies—first Lucy, then children, then Mina.

The fact that his victims become, in turn, potential spreaders of his condition mirrors the fear that a single foreign contaminant could undermine the strength and purity of the nation. The child attacks in Hampstead, reported in the popular press, have the tone of an urban panic: unseen danger touching ordinary families.

Yet Dracula complicates a simple xenophobic reading. The Count is also a product of older European wars and aristocratic violence; his own story casts him as a defender of his land against invaders.

The hunters chasing him back to Transylvania reenact a kind of reverse campaign, using modern imperial mobility—trains, steam launches, consular help—to carry their power into his territory. The final pursuit along rivers and over mountain passes feels like a small expeditionary force operating on foreign soil.

The novel registers both the fear of invasion and the aggressive confidence of an empire that believes it can project force anywhere. In destroying Dracula in sight of his castle, the group asserts a reassuring fantasy: that the empire, armed with modern tools and guided by moral certainty, can confront and eliminate the monstrous “Other” it imagines lurking beyond its borders.

Death, the Un-Dead, and the Boundary of the Self

Vampirism in Dracula is a condition that blurs the line between life and death, self and other. The Un-Dead are not ghosts or simple corpses; they are animated bodies with distorted personalities, driven by hunger and a twisted memory of human feeling.

Lucy’s transformation demonstrates how disturbing this state is for the living. Her friends and fiancé witness her decline through illness and blood loss, then encounter her again as a vampire who retains enough of her former appearance to be recognizable but whose expressions and behavior are horribly altered.

Her sharpened teeth, bloodstained mouth, and seductive cruelty show a self that has been taken over by an alien will while still wearing a familiar face.

Renfield’s case offers another version of this porous boundary. He obsesses over absorbing life by consuming creatures in a chain of increasing size, as if by swallowing other beings he could stave off death or share in Dracula’s strange vitality.

His behavior anticipates the vampire’s method: taking life into oneself through blood. Renfield also reacts directly to Dracula’s presence, suggesting that his mind has become a kind of spiritual sensor.

He exists on a threshold between madness and insight, humanity and something else. The novel uses him to hint that the Count’s influence reaches beyond physical bites, infiltrating minds as well as bodies.

Mina’s mark on the forehead, her psychic link to the Count, and her partial exclusion from holy protections place her in a troubling in-between state. She is neither fully victim nor fully transformed, and the group’s moral struggle includes a terrifying possibility: that they might have to kill her to prevent further evil.

Van Helsing and Seward silently watch her teeth for signs of change, ready to “take steps” if necessary. Her eventual release, signaled by the disappearance of the scar at the moment of Dracula’s destruction, affirms the hope that the self can be restored after corruption.

At the same time, the novel insists that such restoration requires extreme, even brutal actions. Stakes through hearts, severed heads, and sanctified tombs are the price of drawing firm boundaries around life and death again.

The concluding image of Mina as a mother, with a child named after the fallen Quincey, suggests that the human community has reclaimed its continuity from a being who tried to build his own form of immortality out of stolen lives.

Sacrifice, Loyalty, and Redemptive Violence

The band that forms around the fight against Dracula is bound together less by social ties than by shared commitment and sacrifice, and this gives the novel a moral center amid its horrors. Arthur, Seward, and Quincey accept the painful reality of Lucy’s condition and consent to an act that feels, on the surface, like desecration.

Arthur’s willingness to drive the stake through the heart of the woman he loves is framed as an act of love itself: he is freeing her true self from the monster her body has become. The others support him, pray with him, and then complete the grim work of decapitation and purification.

This scene presents violence as morally justified when it restores a victim’s soul and protects the innocent.

Quincey’s death near the castle is the clearest example of heroic sacrifice. He fights through armed guards in hostile terrain, knowing that the odds are against him, and receives a mortal wound in the process.

The group’s reaction to his final moments emphasizes loyalty and shared purpose rather than despair. Quincey himself dies content, pointing to Mina’s unmarked forehead as proof that their mission has succeeded and that his blood has helped redeem her from the curse.

The child later named after him stands as a living memorial, linking his loss to the future of the Harker family and turning individual death into communal continuity.

Mina’s efforts, though less physically violent, are also sacrificial. She works tirelessly, typing painful accounts, forcing herself to confront horrors that others would rather shield her from, and offers her own mind as a channel for information through hypnotic trances, despite the terror it causes her.

Van Helsing, for his part, accepts the burden of performing the most disturbing rituals, from Lucy’s decapitation to the extermination of the vampire women, sparing his companions where he can but never shrinking from what he believes must be done. Together, these acts form a picture of a community willing to endure grief, risk, and moral strain to oppose an enemy who preys on isolation and self-preservation.

By ending with Dracula’s body reduced to dust and the survivors gathered around a dying friend, Dracula suggests that evil can be defeated only at a cost—but that such costly loyalty is precisely what proves the value and resilience of human bonds.