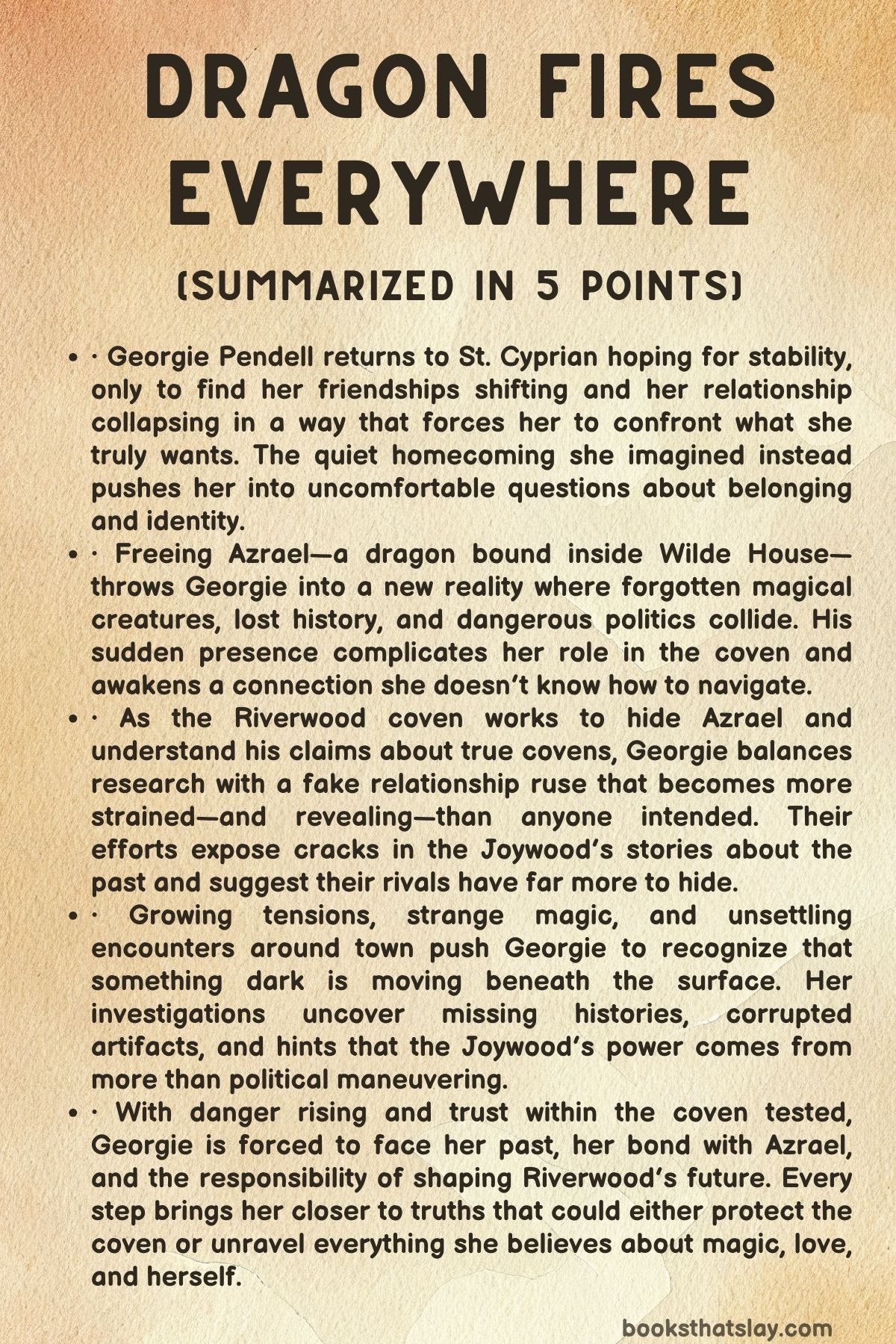

Dragon Fires Everywhere Summary, Characters and Themes

Dragon Fires Everywhere by Hazel Beck continues the story of Georgie Pendell, a young witch stepping into her role as a future Historian of the Riverwood coven. After returning home from a demanding mission, Georgie is thrown into turmoil—emotionally, politically, and magically.

Her life unravels in a single evening, setting the stage for the emergence of an ancient dragon, a corruption spreading through St. Cyprian, and a battle against hidden histories that threaten everything she loves. The book blends romance, mystery, and magic as Georgie discovers the truth about her coven, her past, and her future. It’s the 4th book in the Witchlore series by the author.

Summary

Georgie Pendell returns to St. Cyprian after weeks spent retrieving keys scattered worldwide, a final task before the Riverwood coven can fully assume power.

Though she’s been away, the familiar streets still feel slightly strange, as if she’s reentering a life that once belonged to her but no longer fits perfectly. Arriving at Wilde House, the home she has lived in for years, Georgie feels a growing sense of displacement.

The rooms are too empty, her friends are mostly living with their partners, and the idea of moving in with her boyfriend Sage lingers unpleasantly in her mind.

Seeking comfort, she flies to Jacob’s farmhouse, where the coven is gathered for Thanksgiving. Through the window she sees her friends in warm pairs—each settled, each content.

Her own familiar lies comfortably among them, yet Georgie hesitates, suddenly certain she will disturb their peace. She turns away and instead tries to surprise Sage with an uncharacteristically spontaneous visit.

What she finds is a betrayal delivered with a smile: Sage laughing with Cailee Blanchard, fully entangled in an affair. Georgie ends the relationship immediately, more angry with herself than with him, ashamed she ignored her instincts for so long.

Returning to Wilde House in tears, Georgie discovers something impossible—a children’s fairy-tale book from her past lying on the stairs. Drawn to it in her vulnerable state, she reads her favorite vow aloud.

As the final words leave her lips, the staircase shakes and the carved dragon at the base cracks open, releasing smoke and light that form first a massive dragon and then a striking man with dragon features. He calls himself Azrael and claims to have been trapped within the wood for more than a century, fully conscious the entire time.

The coven arrives in a panic, finding Georgie standing beside a dragon turned man. The encounter becomes even more tense when Azrael and Frost instantly recognize each other as enemies.

Azrael accuses the former Joywood coven of destroying magical creatures so they alone could maintain power. He reveals that every ruling coven needs a magical creature as a member, and that the Joywood eliminated nearly all of them to ensure no other coven could ascend.

Some survivors, like Azrael and a mermaid named Melisande, were cursed into objects—hidden in plain sight.

The Riverwood coven is shaken by these revelations. Though they refuse to let Azrael dictate their choices, they acknowledge the danger he faces if the Joywood learn he is free.

To protect him, Georgie proposes creating a powerful glamour with Frost’s help so Azrael can move through town undetected. Ellowyn suggests a cover story: Azrael will pretend to be Georgie’s new boyfriend.

Georgie reluctantly agrees, still hurt from her breakup but understanding the necessity.

Azrael quickly disrupts Georgie’s sense of stability. He appears in her room without invitation, carries her through the night sky in dragon form, and reveals he has been quietly protecting and comforting her for years from within the newel post.

Confused by her connection to him, Georgie throws herself into research, discovering evidence that covens were originally meant to include a magical creature. With the glamour spell cast successfully, Azrael begins appearing in town under the name Pete, drawing attention everywhere he goes.

His bold, unfiltered nature clashes with Georgie’s desire for privacy, especially when he pressures her publicly about her breakup. This leads to a painful confrontation, and Georgie temporarily distances herself from him.

She confides in her friends, receives their support, and dives deeper into uncovering truths about the Joywood. At the Cold Moon Ball, Azrael apologizes and gives her a necklace.

Their plan for ascension is jeopardized when Azrael learns that the Joywood expect the Riverwood to fail without a magical artifact tied to a creature. Since Azrael must remain hidden, he sets out to secure one before the ritual.

But the danger soon turns deadly. A strange melody near the river lures Georgie into a trap of black water and mud that nearly kills her.

Azrael rescues her in dragon form, but the Joywood use the chaos to turn the crowd against him, claiming he is the threat. Despite Georgie’s protests, Azrael agrees to imprisonment, insisting this will prevent further conflict.

He is confined to the cemetery, where he can appear but cannot leave. There, he warns Georgie that dark magic remains active and that her crystals have been corrupted.

Her mother’s involvement is uncertain, deepening Georgie’s unease.

The archives finally open to Georgie again once the cursed objects are purged. She learns through a past-life ritual that she and Azrael have been linked for centuries, always ending in death.

Azrael demands she stop risking herself, which leads to a bitter argument. Georgie refuses to abandon her coven to spare herself—and refuses to let him dictate her choices.

As the Riverwood prepare for Emerson and Jacob’s winter wedding, Emerson proposes using the ceremony as a magical broadcast, believing that vows spoken aloud might free other cursed creatures just as Azrael was freed. Georgie agrees, though she prepares contingencies.

The coven soon learns that many Joywood members are dead and that Carol—the remaining leader—is dangerously powerful.

During the wedding, Carol unleashes a monstrous, stitched-together creature and a tornado of black magic. Meanwhile, Georgie sneaks into Carol’s home to search for answers and discovers the truth: Carol murdered her own coven, corrupted their magic, and created the monster now attacking the town.

Controlled through Desmond Wilde, she nearly kills Georgie. Azrael breaks free just long enough to save her, and together they destroy Carol’s black-magic library and escape.

Returning to the wedding, Georgie rides Azrael into battle. The fight becomes desperate until Emerson and Jacob complete their vows.

The magic spreads through St. Cyprian, releasing every remaining magical creature.

United, witches and fabulae drive Carol into the center of town. She dissolves into black ooze, which is sealed into a gem within the public dragon statue.

Peace slowly returns.

A year later, the Riverwood coven has rebuilt a better world—archives open, magical history restored, new beings living openly among witches. Georgie and Azrael build a life together in Wilde House, working alongside their coven and their newly freed allies.

They end the year flying over their home, hopeful and finally free to live the love that once cost them everything.

Characters

Georgie Pendell

As the future Historian of the Riverwood coven, Georgie stands at the emotional and narrative core of Dragon Fires Everywhere. Her character carries the weight of legacy, duty, and identity, yet she begins the story feeling displaced—wandering the world retrieving keys, returning to a home that no longer feels wholly hers, and navigating a relationship that never truly fit.

She is brilliant, deeply intuitive, and fiercely loyal, but struggles with vulnerability, especially in the presence of those she loves. Her breakup with Sage exposes her fear of settling for less than she deserves, while her interactions with the coven reveal her chronic tendency to shoulder burdens alone.

Georgie’s relationship with Azrael awakens a part of her that has been dormant—instinctive, brave, and emotionally open—but their bond also forces her to confront the cost of love and the cycles of loss embedded in their past lives. Through heartbreak, betrayal, responsibility, and destiny, Georgie evolves from a self-doubting young witch to a formidable leader who chooses courage and unity over fear.

Her arc is about reclaiming her story, rewriting history—not only for witchkind, but for herself.

Azrael

Azrael, the dragon cursed into the Wilde House newel post, arrives in the narrative as an overwhelming force—dangerous, magnetic, ancient, and impossibly intertwined with Georgie’s life. His personality marries arrogance with devotion; he is protective to the point of recklessness and confident to the edge of infuriating, but underneath lies centuries of loneliness and trauma inflicted by the Joywood.

His deep resentment toward Frost and enduring disdain for ruling covens underline his history as a victim of magical oppression. Azrael’s connection to Georgie is not merely romantic—it is cosmic, forged across lifetimes, and fraught with repeating tragedy.

Despite his power, he grapples with fear: fear of losing her again, fear of the curse returning, and fear that destiny will always demand sacrifice from him. His growth emerges through learning to trust Georgie and her coven, accepting that unity—not solitary strength—is what breaks the cycles of destruction.

By the end, Azrael becomes not only her lover but her partner in leadership and hope, embodying the restored bond between witches and fabulae.

Emerson Wilde

Emerson is the heart-steadying force of the Riverwood coven: grounded, warm, and resolute. As a natural leader, she balances compassion with pragmatism, often guiding the coven with a clear-eyed sense of what must be done.

Her relationship with Jacob roots her even further, and their wedding becomes a magical turning point for the entire magical world. Emerson’s ability to pivot from domestic details—organizing a town-wide ceremony in days—to wartime strategy underlines her exceptional adaptability.

She is the first to see the symbolic and literal power of love as magic, transforming her wedding vows into a revolutionary tool. Emerson’s strength lies not in grand displays of power but in her unwavering belief in unity, community, and the emotional ties that bind people together.

She becomes a mirror to Georgie, showing what leadership grounded in love and partnership can look like.

Rebekah Wilde

Rebekah is sharp, perceptive, and fiercely protective of the people she loves. Her wariness around Azrael reflects both historical trauma and her keen instincts.

She is one of the first to caution Georgie that dragons are unpredictable, not out of malice but out of a grounded desire to safeguard her friend and the coven. Rebekah’s connection to Frost adds complexity to her role—she sees both his successes and shadows, pushing him toward accountability and growth.

Beyond her relationships, she serves as a researcher and strategist, bridging the emotional and intellectual needs of the coven. Her resilience and clarity make her one of the most formidable witches in Riverwood.

Ellowyn Pendell

Ellowyn’s presence brings gentleness, insight, and quiet strength to the coven. Her pregnancy during much of the story highlights her bravery—navigating danger while nurturing new life and preserving her optimism.

She often acts as Georgie’s emotional anchor, offering kindness without judgment and supporting her even when Georgie refuses to ask for help. Ellowyn has a subtle but profound connection to magic and intuition, seen when she receives the fairy-tale book and when she felt the early clues of the true coven structure.

Her ability to balance familial love, personal vulnerability, and coven duty enriches the emotional tapestry of the story.

Zander

Zander is gentle-hearted and steady, contributing quiet wisdom and emotional grounding to the coven. His talents are less flashy but deeply essential—he assists in rituals, supports Ellowyn, and acts as a stabilizing presence during escalating conflict.

As the coven navigates threats from Carol and the Joywood, Zander becomes an integral emotional counterweight, ensuring the group remains interconnected and compassionate during crisis.

Jacob

Jacob’s combination of practicality, loyalty, and bravery makes him a pillar of reliability within both the coven and the broader community. His partnership with Emerson showcases him as someone who nurtures strength in others while standing steadfast in moments of danger and instability.

His medical and magical skills save lives, including during the black-magic attack on his sister. Jacob’s unwavering moral compass and devotion to Emerson embody the theme of love as magic.

Nicholas Frost

Frost is one of the most complex figures in the narrative—a former immortal Joywood member seeking redemption. He carries the weight of past atrocities, including the believed death of a unicorn, and his guilt shapes his interactions with the coven and Azrael.

Frost’s sharp intellect and strategic thinking make him indispensable, but his stoicism often masks deep emotion and regret. Through supporting the Riverwood coven and working tirelessly to dismantle the Joywood’s lies, Frost demonstrates that redemption is not achieved through denial but through active, ongoing atonement.

His uneasy history with Azrael gives the story tension, but their eventual alignment in purpose reflects the larger theme of unity overcoming legacy.

Sage

Sage serves as Georgie’s symbolic starting point—a reminder of what love should not be. His infidelity is not merely betrayal but a revelation: he was a relationship she forced herself to maintain out of expectation, habit, and fear of loneliness.

His controlling demeanor and emotional disconnect stand in stark contrast to the passion, honesty, and instinctive connection Georgie later experiences with Azrael. Sage embodies complacency, stagnation, and the danger of settling for less than one’s truth.

Carol

Carol is the chilling embodiment of corrupted leadership, obsession with power, and the destructive nature of fear. As the last surviving force of the Joywood coven, she clings to control with increasingly unstable magic, manipulating memories, people, and entire histories to uphold her authority.

Her descent is marked by desperation—evident in the weakening of her magic, her attempts to manipulate Georgie, and her creation of monstrous constructs to maintain dominance. Carol’s villainy lies not only in her dark magic but in her unyielding belief that she alone deserves power.

Her final dissolution into black ooze symbolizes the collapse of a legacy built on deception, cruelty, and fear.

Melisande

Melisande, once trapped as a chandelier, brings wit, mystery, and depth to the world of fabulae. Her freedom reveals her resilience and strategic intelligence—she moves in secrecy, gathering information and waiting for the right moment to act.

Her loyalty to Georgie and the Riverwood coven, as well as her broader commitment to freeing her people, underscores the central theme of interspecies unity. She is a reminder that the Joywood’s tyranny extended far beyond witches and that the future of magic depends on cooperation between all magical beings.

Stanford Pendell

Stanford represents unconditional love, chosen family, and moral clarity. Though not Georgie’s biological father, he chose her fully and continues to stand beside her even when confronted with dangerous truths.

His presence grounds Georgie emotionally, giving her courage to face the ghosts of her past—both literal and metaphorical. Stanford’s support during the infiltration of Carol’s house demonstrates his bravery and the depth of his devotion.

He is a reminder that love—non-magical, quiet, steadfast love—is a power of its own.

Desmond Wilde

Desmond is a tragic casualty of Carol’s manipulation. Once a respected member of the magical community, he is reduced to a puppet through dark magic, forced into violence that is not his own.

His possession represents the ultimate violation of autonomy and the Joywood’s disregard for life. His role in the story emphasizes the stakes of Carol’s domination and the cruelty inherent in her pursuit of power.

Themes

Love, Soulmates, and the Choice to Live Rather Than Die for Love

Georgie and Azrael’s connection in Dragon Fires Everywhere is framed from the beginning as the kind of once-in-a-hundred-lifetimes bond that fairy tales promise. The fairy-tale book she rereads on the stairs, the vow she recites, and the dragon bursting from the newel post all signal a story that has already been written for them many times over.

The past-life regression confirms this: in life after life, they are pulled together in sweeping romance, only for one of them to die violently. Love in this world has literally been scripted as a sacrifice.

That pattern is reinforced by the Carol/Joywood legacy, where love, loyalty, and coven bonds are tools to be weaponized and consumed.

What makes this book’s treatment of love striking is the way Georgie repeatedly refuses the idea that a soulmate bond automatically deserves obedience. She rejects Sage the moment his cheating is revealed, refusing to let history with him or his demands for a conversation give him power over her.

Later, with Azrael, she pushes back even harder. When he tries to protect her by demanding she prioritize survival over confronting the Joywood curse, she calls him selfish and cowardly, not because she doubts his love, but because she will not accept a love that requires her to betray her sense of responsibility.

Their relationship only stabilizes when he starts treating her choices as equal in weight to his fears.

Love, then, is not portrayed as a force that absolves anyone of accountability. It can empower, heal, and quite literally reshape magic, but only when it respects autonomy.

Emerson and Jacob’s wedding is the turning point: their vows, drawn from the fairy-tale book, send a wave of love through St. Cyprian that frees magical creatures, not because it is sentimental, but because their relationship model is grounded in partnership, consent, and mutual risk.

That wave of love is not about dying for someone; it is about standing beside them. The final scene, with Georgie and Azrael flying over the town having chosen to live their love instead of die for it, marks a radical revision of the fairy-tale script.

Love stops being the tragic climax and becomes a long, sustained act of living together.

Power, Governance, and the Ethics of Leadership

From the opening, Georgie’s unease about stepping into her role as Historian of the Riverwood coven sets up a constant examination of what it actually means to hold power. The Joywood’s reign is a cautionary example: a ruling coven that literally slaughtered or cursed magical creatures in order to monopolize immortality, altered historical records to hide their crimes, and used dark magic and mind control to keep their status unchallenged.

They have power for its own sake, and every system around them—archives, memories, even family bonds—is bent toward keeping them in place. Carol is the distilled form of that abuse: she kills her own coven, harvests their power, commands constructs like the stitched-together monster, and even uses Desmond’s body as a mouthpiece.

For her, leadership means consumption, control, and terror.

Against that backdrop, Riverwood governance is messy, slow, and full of dissent. They argue over Azrael’s place, debate how to handle Joywood aggression, and vote repeatedly on his imprisonment and release.

Emerson’s editorial a year later reads almost mundane—school wings, hospitals, editorials, collaborative projects with crows—but that mundanity is exactly the point. Ethical leadership in Dragon Fires Everywhere is shown as administrative, collaborative, and often unglamorous.

Georgie, Emerson, Frost, and the others constantly have to consider unintended consequences: hiding Azrael with a glamour might protect their advantage but also risks repeating Joywood secrecy; involving fabulae in ascension could recreate the old pattern of using magical beings as tools.

Power here is at its best when it is shared and transparent. The true-coven diagram that expands membership to eight—including a fabulae—redefines leadership as something larger than a tight inner circle.

Even the final battle showcases a new model: witches, ghosts, humans, and freed magical creatures all contribute to defeating Carol, and the spell that locks her away uses Joywood methods repurposed under community consent. Georgie’s sword of unity is not a token of solitary rule; it is a reminder that leadership is an ongoing agreement between many parties.

The book suggests that real power does not rest in the ability to control others but in the willingness to spread authority, tell the truth about history, and accept that leadership is always accountable to those it serves.

History, Memory, and Who Controls the Story

As future Historian, Georgie sits at the heart of the book’s obsession with who records events and whose version of reality becomes law. The Joywood coven has literally rewritten the past: they hide records of their atrocities, erase the existence of dragons, mermaids, and other fabulae from mainstream witch knowledge, and lock their darkest texts in Carol’s private library rather than in public archives.

This manipulation is not just academic. It shapes what witches believe is possible, what they consider mythical versus real, and how they interpret their own magic.

When witches grow up thinking dragons are fairy tales, they cannot imagine a world where fabulae have rights, agency, or a place in leadership.

Georgie’s relationship with the archives dramatizes the tension between truth and censorship. When her crystals are corrupted by dark magic, the archives refuse to cooperate, as though the institution itself recognizes it has been compromised.

Only after she destroys those tainted items does the archive open to her again, offering books about dragons, black magic, and, tellingly, past-life regression instead of direct Joywood lore. Even the way information arrives—an unexpected book, a fairy-tale retelling, a twisted story buried in Carol’s hidden chamber—shows how truth has to be recovered piece by piece, often from sources disguised as fiction.

The fairy-tale book itself, with its changing cover and shifting illustrations, is a physical reminder that stories can be altered to either hide horror or expose it.

When Emerson and Jacob turn their wedding into a broadcast of love-based vows from that same book, they essentially overwrite Joywood’s revisionist history. The words echo through witchdom, not as propaganda but as a public, magical record of what love and unity can accomplish.

The final editorial Georgie reads a year later—the true-history textbook, Lillian’s fairy tale in print, open archives—signals that the Riverwood coven understands that governance without honest history is just another form of tyranny. Dragon Fires Everywhere insists that memory is a battleground: whoever controls the narrative controls what future generations think is normal, inevitable, or impossible.

Georgie’s arc as Historian is not about dusty books; it is about protecting the right of everyone to know what really happened and to imagine something better.

Identity, Self-Worth, and Claiming One’s Own Power

Georgie’s personal journey begins with a quiet dissonance: she has helped save St. Cyprian, is about to become Historian, yet she stands outside Jacob’s farmhouse window convincing herself she is a seventh wheel who might upset the warmth inside.

That sense of not quite belonging radiates through many aspects of her life—her strained intimacy with Sage, her uncertainty about moving out of Wilde House, her complicated feelings about being Stanford’s daughter but not by blood, and her anxiety about stepping into a position that requires confidence in her own judgment. Her first instinct after being cheated on is not heartbreak over the relationship but shame that she “settled for a man beneath her,” which reveals how low her expectations for herself have been.

Azrael’s appearance tests and reshapes her self-worth in several directions. On one hand, he has literally watched her grow up, secretly providing crystals after hard nights, charmed by her long before she freed him.

That devotion could easily have turned into a dynamic where his adoration defines her value. Instead, the story keeps showing Georgie pushing for her own agency: she sets boundaries after he invades her bedroom space, challenges his decisions, refuses to keep secrets about Sage when he pressures her, and ultimately confronts him when he demands she avoid danger for his peace of mind.

Her decision to undergo past-life regression, even knowing it might reveal terrifying patterns, is a declaration that she will not let anyone else decide what she can handle.

The revelations about her mother’s role in the corrupted crystals and the necklace add another layer. Georgie has to face the possibility that even those who were supposed to protect her may have been compromised, intentionally or not.

Rather than collapse, she widens her definition of family to include Stanford, who chose her knowing she was not biologically his, and her coven, who stand beside her in battle and in research. By the end of Dragon Fires Everywhere, Georgie’s identity is not limited to titles or bloodlines.

She is Historian not because of a job description, but because she insists on truth; she is a partner to Azrael not because fate says so, but because she demands respect and equality; she is a daughter because love was chosen and sustained. Her sense of self grows from someone who watches through windows to someone whose choices shape the future of an entire world.

Found Family, Community, and Belonging

The Riverwood coven is introduced as a cozy domestic scene Georgie observes from the outside: couples at dinner, familiars curled contentedly, laughter and warmth spilling through a farmhouse window. That image crystallizes both the comfort of found family and the pain of feeling excluded from it.

Georgie’s decision to turn away rather than knock captures how belonging is not only about whether others will welcome you, but whether you believe you deserve to be inside. The narrative keeps returning to shared spaces—Wilde House, the tea shop, the bookstore, the archives, Main Street during the wedding—as places where community is built through everyday rituals, not just big magical moments.

At the same time, the book does not pretend that community is frictionless. Georgie hides Sage’s betrayal from her friends, fearing their pity; when Azrael forces the issue, it blows open a wound in her relationship with them.

The coven disagrees about Azrael’s presence, his imprisonment, and how much risk they should assume for him. Georgie’s mother is chosen to help imprison Azrael, a choice that slices through Georgie’s loyalty to both family and coven.

Even the vote to free Azrael is agonizingly slow, reflecting how fear, past trauma, and differing priorities complicate solidarity. Yet conflict never erases the underlying commitment these witches have to one another.

When Georgie finally confesses the truth about Sage, her friends’ immediate outrage on her behalf reaffirms that she is not alone; when the cemetery statue becomes Azrael’s boundary, they still gather there, strategizing together.

The final battle is the community’s ultimate test. Carol uses fear to fracture the town, blaming the dragon and trying to resurrect the old Joywood hierarchy.

Riverwood responds not with a single hero but with a network: Emerson organizing defenses, Jacob healing, Zander carrying news, Melisande bringing river allies, ghosts stepping into the fray, human townsfolk refusing to accept Carol’s narrative. Belonging expands beyond coven lines to include freed fabulae, crows, centaurs, and more.

A year later, the editorial listing hospitals, schools, and cooperative projects makes clear that the victory was not a one-night event but the start of a long-term communal project. Dragon Fires Everywhere treats found family not as a soft background detail, but as the bedrock that allows individuals like Georgie to risk themselves, challenge each other, and still trust that they have a place to return to.

Prejudice, Otherness, and Justice for the Fabulae

The treatment of dragons, mermaids, unicorns, and other fabulae exposes a deep history of prejudice running through witch society. The Joywood coven’s strategy depended on framing magical creatures as extinct, mythical, or dangerous.

By cursing or slaughtering them, binding survivors into objects, and then erasing them from official histories, they ensured that witches would see fabulae as either legends or threats rather than as people with their own cultures and rights. Azrael’s accusation that Frost belonged to the coven that hunted fabulae forces the Riverwood witches to confront not only external enemies but complicity and inherited guilt.

Frost’s belief that he killed a unicorn in his quest for immortality shows how deeply the old system convinced even individuals that monstrous acts were necessary.

Once Azrael is freed, his very existence destabilizes ingrained prejudices. Witches instinctively fear him in dragon form, even when he has just saved Georgie’s life.

Carol and the Joywood exploit that fear, urging the townspeople to see him as a menace rather than a protector. The cemetery imprisonment decision, with its requirement for “neutral” witches from both covens, reflects a community still half-trapped in old assumptions about what safety means.

Even Georgie’s initial plan to keep Azrael hidden under glamour so he can pose as her human boyfriend is shaped by the belief that the world will not yet accept a dragon openly among them.

Justice for fabulae emerges slowly and is tied to visibility and participation. Melisande’s admission that she was freed when Azrael was but chose to remain quietly active reveals how survival sometimes requires hiding even after chains fall away.

Her promise that river creatures will stand with Riverwood if her people are freed reframes fabulae as allies, not tools. The true-coven diagram formally includes a fabulae among the leaders, challenging centuries of exclusion.

In the final battle, the moment when freed creatures flood into the conflict alongside witches and humans acts as both reparation and revolution: they are not reinforcements summoned at the last second, but co-owners of the world being rebuilt. By the time a fabulae school and hospital wing exist, Dragon Fires Everywhere shows that justice is more than rescue.

It is structural change—education, healthcare, shared governance—that acknowledges fabulae as essential members of the magical community rather than footnotes in someone else’s story.

Generational Harm, Corruption, and the Seduction of Dark Magic

Carol is the obvious face of corruption, but the roots of dark magic in Dragon Fires Everywhere extend far beyond one villain. The Joywood model of immortality demands that each generation commits atrocities to maintain its power.

That expectation filters into individual choices: Frost believes he killed a unicorn, Joywood witches participate in mind control or look away from what they suspect, and even well-meaning characters carry objects tainted by black magic without realizing it. The corrupted crystals Georgie has relied on for comfort, including the necklace from her mother, show how easily care can be tangled with harm when a system is steeped in secrecy and compromise.

Her mother’s participation in the spell that imprisons Azrael deepens this tension; love and complicity sit side by side in the same person.

Dark magic itself is shown as seductive not only in power but in clarity. Carol’s vision of the world is simple: strength comes from domination, and fear keeps order.

The stitched-together monster and the black tornado at the wedding are expressions of that philosophy—terrible, but straightforward. By contrast, the Riverwood approach is slower and full of uncertainty: they argue, second-guess, and repeatedly rewrite plans.

It would be easy, the book suggests, to fall back into Joywood methods under the justification of “using their own spells against them. ” In fact, Georgie and Azrael do repurpose a Joywood containment spell to seal Carol’s essence into the public dragon statue, but they do it openly and with collective consent, turning a tool of oppression into a safeguard watched by many eyes.

Generational harm is finally confronted when Georgie chooses to see the whole picture, even when it implicates people she loves. Her past-life regression reveals cycles where she and Azrael have been caught in scripts that end in death.

The black water attack by a stitched-together horror that combines Felicia and Maeve reveals Joywood’s willingness to weaponize the dead. By naming these patterns and refusing to accept them as destiny, Georgie and her coven break the chain.

Emerson and Jacob’s vows, the freeing of cursed fabulae, and the public acknowledgment of Joywood crimes mean a new generation will grow up with full knowledge rather than inherited silence. Corruption does not vanish overnight, but the book ends with a community that has chosen difficult honesty over comforting lies, making it much harder for dark magic to masquerade as tradition again.

Truth, Transparency, and Emotional Honesty

Secrets haunt nearly every relationship in Dragon Fires Everywhere. Georgie hides Sage’s cheating from her friends, ashamed and afraid of pity.

Azrael lurks in her bedroom and in her life with a century’s worth of unspoken knowledge about her family and Wilde House, offering crystals anonymously and deciding when to interfere. Georgie’s parents withhold the full truth of her parentage, and her mother unknowingly—or perhaps knowingly—arms her with corrupted crystals.

The Joywood coven builds its entire rule on half-truths and omissions, using erased history and controlled narratives to keep witches compliant. Even the archives participate in this pattern by withholding information when tainted items are present.

The story repeatedly shows how secrecy warps connection. Georgie’s silence about Sage isolates her at the very moment she needs support; when Azrael forces the issue in public, she feels betrayed even though his goal is to push her toward honesty.

Their own bond is strained when he insists she trust his warnings without explaining the full scope of his fears. The coven’s delay in voting to free Azrael stems partly from a lack of full knowledge—about Joywood decline, about the true nature of fabulae, about the history bound up in Carol’s house.

Carol herself remains powerful as long as the town accepts her version of events at face value.

Healing begins whenever someone chooses to speak fully. Georgie’s confession to Emerson, Rebekah, and Ellowyn about Sage transforms her breakup from a private humiliation into an occasion for shared anger and solidarity.

Stanford’s conversation with Georgie outside Wilde House, where he states plainly that he chose to love and raise her even knowing she was not his biological daughter, stabilizes her sense of being wanted. The archives opening once the corrupted crystals are destroyed reinforces the idea that transparency—being willing to see what is contaminated and remove it—is a prerequisite for real knowledge.

Emerson and Jacob’s wedding, with its publicly broadcast vows and visible use of fairy-tale text, turns intimacy into a communal affirmation rather than a hidden ritual.

By the end of Dragon Fires Everywhere, emotional honesty is as vital as magical skill. Georgie and Azrael can only step into their shared future once he respects her autonomy enough to stop making unilateral decisions in the name of protection and once she trusts him enough to share the burden of her visions and fears.

The coven’s governance relies on open editorials, accessible textbooks, and shared archives rather than private whispers. The book suggests that truth, while often painful, is the only ground on which enduring love, ethical power, and a just community can stand.