Dust Storm Summary, Characters and Themes

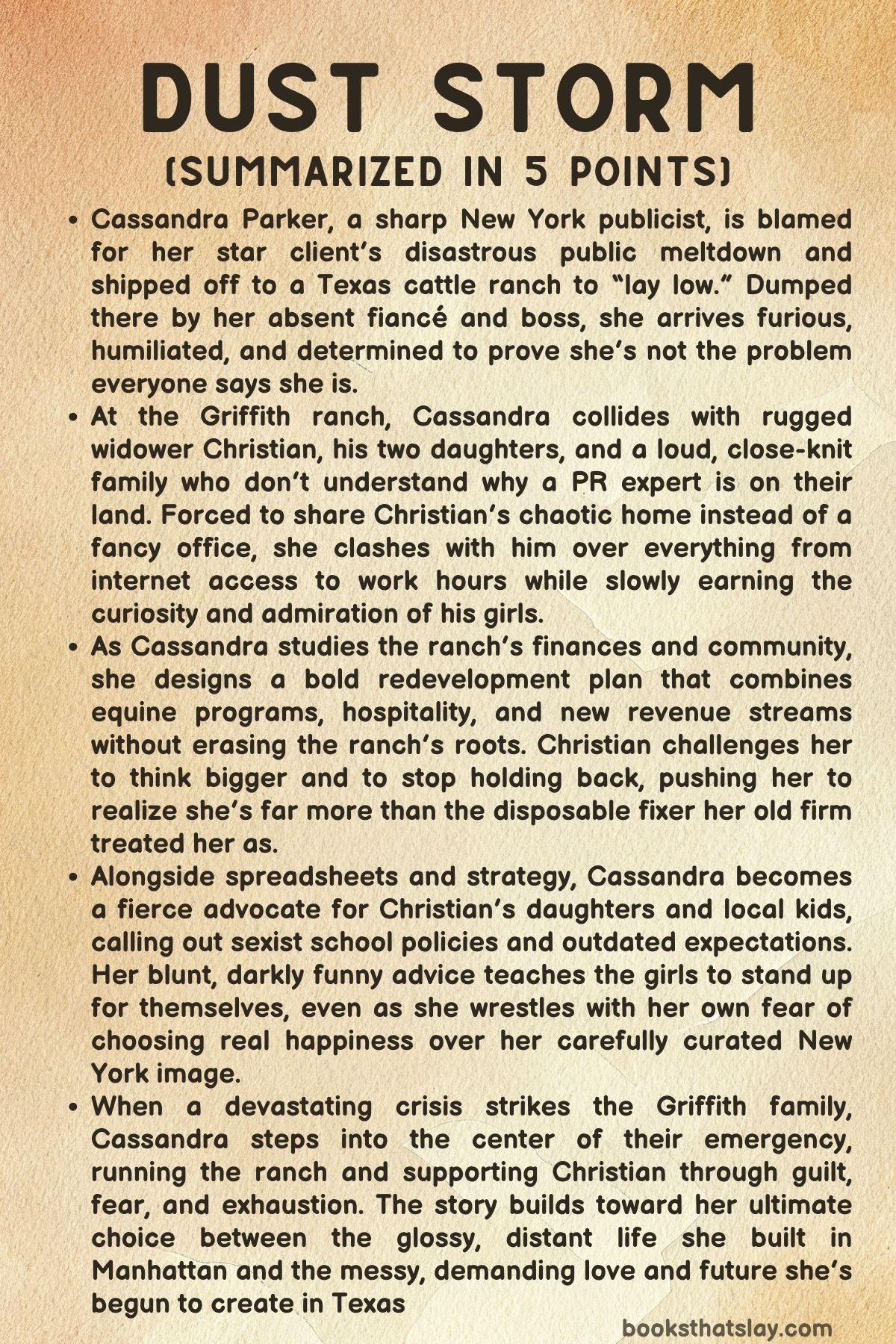

Dust Storm by Maggie C. Gates is a city-girl-meets-cowboy romance about blowing up the life you thought you wanted and building something better from the wreckage. Cassandra Parker is a razor-sharp New York publicist whose career implodes after a client’s public meltdown, and she’s shipped off to a Texas cattle ranch as damage control.

There she crashes into Christian Griffith, a widowed rancher raising two daughters and guarding his heart. Between school fights over sexist dress codes, cattle emergencies, bull riding, and big-money development plans, they slowly create a new family—and a future that finally feels like their own choice.

Summary

In Dust Storm, Cassandra Parker is at the top of the New York PR world when it all caves in. During an awards show, her volatile actress client Lillian Monroe gets drunk and publicly accuses Cassandra of manipulating her, paying off judges, and abusing her power.

The scandal explodes across the media. Instead of backing Cassandra, her fiancé and boss, Tripp Meyers, orders her to leave Manhattan and “lay low” by taking a “business development” project in Texas.

Cassandra recognizes the truth: she’s being exiled to protect the firm, and her three-year engagement is looking more like a branding asset than a relationship.

Cassandra flies to Texas with Tripp and arrives at the Griffith Brothers Ranch, owned by Tripp’s sister-in-law Becks’s family. She meets patriarch Silas Griffith and his son Christian, a widowed rancher and single father.

Tripp immediately insults the rural setting, tries to talk numbers, and behaves like the ranch is a failing account. Christian is unimpressed.

Things get worse when Tripp falls into manure in front of everyone, then marches Cassandra to a long-abandoned cabin that is crawling with dust, a rat snake, and occupied by Gracie Griffith’s pet cow, Mickey. Horrified, Cassandra wants to leave, but Tripp abruptly announces he’s going back to the airport for “work,” abandoning her at the ranch without a second thought.

Stranded, Cassandra reluctantly accepts Christian’s offer to stay at his house “for now.” She’s terrified of his big mare Libby, but he coaxes her onto the horse and takes her home, where she meets his daughters, thirteen-year-old Bree and eleven-year-old Gracie. The girls are instantly fascinated by the glamorous outsider.

Cassandra watches Christian’s nightly chaos—homework, hair brushing, bedtime—and learns his wife died when the girls were small. The house is cluttered but warm, and Cassandra, nursing resentment toward her absentee fiancé, starts to wonder what it would be like to belong somewhere.

The next days are a clash of worlds. Christian wakes before dawn; Cassandra prefers a late start.

He uses his dog Sadie to drag her out of bed when she refuses to get up. At the ranch office she recoils from the sight of a cow lounging indoors, while he shrugs and reminds her she’s on a cattle ranch.

He drags her along on an ATV to check calves, and she clings to him as they bounce across the pastures. Meanwhile, some ranch hands resent her presence, especially Jackson, who crudely objectifies her and blames her for their lack of raises.

Christian publicly shuts him down and announces that Cassandra carries the Griffith name while she’s there, warning the crew they’ll answer to him if they disrespect her.

At night Cassandra waits for a call from Tripp, who is in Spain with Lillian. When he finally contacts her, he brushes off the scandal, dodges any real discussion of their relationship, and hangs up.

Hurt and furious, Cassandra eats ice cream spiked with whiskey on the porch until Christian swaps it for real food, fusses over her blistered feet, and gives her socks and boots. Later he takes her on a nighttime ride on Libby, sitting behind her and teaching her how to move with the horse.

Under the stars, their banter turns personal. She admits her engagement is cold and sexless; he bluntly suggests Tripp is cheating.

There is charged tension when they dismount, interrupted only by Mickey clomping onto the porch in pool noodles.

As Cassandra spends more time with the girls, her sharp edges become useful. On the way to school, Gracie explains she’s expected to “help” a disruptive boy stay focused.

Cassandra firmly tells her she’s not responsible for his behavior and coaches her to prioritize her own learning. Christian is surprised but grateful.

In town, he quietly pays for Cassandra’s manicure and new boots, explaining he just wants to make her stay easier, even as he insists he will still push her hard on work.

Cassandra dives into the ranch’s finances and assets and designs a practical plan focused on equine programs: boarding, lessons, camps, and therapy partnerships. Christian reads it and says it’s good—but not ambitious enough.

He wants her to think bigger. Frustrated, she finally admits the truth: after Lillian’s meltdown, the firm gave her a choice between this impossible Texas assignment or being fired.

On the porch that night, she makes him swear to keep her story confidential and describes how she protected Lillian, arranged rehab instead of jail, supervised her at the awards show, and still got framed as the villain. Tripp refused to back her up and instead took Lillian on as his own client overseas.

Christian listens and tells her he sees her value and isn’t just tolerating her.

When Bree is humiliated by a substitute teacher over her blouse being “distracting,” Christian and Cassandra go to the middle school together. Cassandra calmly lets the principal, Beeker, reveal her bias, then dismantles her arguments point by point, accusing her of sexualizing a minor and abusing authority.

She reveals she has been recording the conversation and threatens to take the issue to the school board and beyond. Beeker backs down.

The adrenaline from defending Bree tips Cassandra and Christian over the line. Back at the house, he gives her a clear choice: if she wants him, she has to say so.

She chooses him, and they have intense, consensual sex where Christian is dominant but careful, focused on restoring her sense of desirability after past partners and Tripp’s neglect. Cassandra has already mailed her engagement ring back to Tripp, ending things for good.

After a brief panic and avoidance spiral, Cassandra returns to the ranch and to Christian. He reminds her not to disappear on his daughters, who were counting on her.

Together, they refine her bigger vision: the Griffith Brothers Ranch Revitalization Project. It expands the equine program, leases land for renewable energy and cell towers, and eventually presses into a farm-to-table restaurant, inn, spa, and event venue.

Cassandra uses her contacts to secure a tentative ten-million-dollar investment from Lawson International. Christian, wary of outside money and knowing his brother CJ will resist, nevertheless agrees to move forward.

Cassandra proves equally formidable with local politics. When the mayor shows up fishing for information and dismisses her as window dressing, she meets him on horseback and coolly corners him, tying his support for their project to his own reputation and secrets.

Later she meets Christian’s wild, tattooed brother Ray, who lets the girls color his ink with markers, and sees how fiercely this family loves one another despite their chaos.

The groundbreaking ceremony for the new development becomes Cassandra’s masterpiece. She coordinates sponsors, catering, parking, décor, and transforms the ranch into a showpiece.

Christian finds her hiding in the office checking emails and presents her with handmade heel guards stained to match her shoes so she can walk on the dirt. Touched, she lets herself feel how deeply he sees her.

At the party, Cassandra gives a speech about the future of the ranch and invites the whole Griffith family to turn the first shovelfuls of earth. Afterwards, she tells Christian she has resigned from her New York firm and accepted his job offer at the ranch, housing stipend included.

She is choosing him, the girls, and this life.

Soon after, the family travels to Houston for Ray’s championship bull ride. Cassandra, now in boots and a ranch-logo jacket, is firmly part of the crew.

She is horrified watching the danger of the sport and devastated when Ray is thrown and trampled by the bull Homewrecker. In the chaotic aftermath, Christian rushes into the arena while Cassandra gathers the girls and later shepherds everyone through the hospital ordeal.

As Ray undergoes emergency surgery, Christian drowns in guilt and traumatic memories of past losses. Cassandra makes him eat, walk, talk, and finally accept that he cannot control everything.

In that charged, exhausted space, she tells him she loves him.

Ray survives but is left a quadriplegic. The Griffiths reorganize their world: rotations at the hospital, renovations to house him, and constant medical needs.

While they focus on Ray, Cassandra quietly keeps the ranch running—handling staff, school runs, finances, and emotional triage. She starts doing Bree and Gracie’s hair in the mornings and sinks into a genuine parental role.

One day the girls tell her they love her; she says it back, then nervously reports it to Christian, who confesses they had been practicing how to say it.

News breaks that Tripp has been arrested for embezzling from his celebrity client, confirming his corruption and vindicating Cassandra in the eyes of the wider world. By then, though, she no longer needs New York’s approval.

Her life and loyalty are rooted on the ranch. When Ray finally wakes in ICU, Christian places his championship buckle in his hand and tells him he won the title he fought for.

Christian lists Cassandra as family with the hospital and tells her he is certain of three things: the sun will rise, his girls love her, and she was meant to be part of them.

Months later, in the epilogue, Cassandra is officially a Texas resident living with Christian and the girls. She takes Bree on a trip to New York for Broadway shows and shopping, then brings her “best evil stepmother” self back home.

Christian rides with Cassandra out to the future lodge site at sunset and says the first wedding there should be theirs. He proposes with a sleek ring, repeating his three certainties and asking her to share his name.

Cassandra accepts, fully committed to the ranch, the project she helped build, and the family who chose her as much as she chose them.

Characters

Cassandra Parker

Cassandra begins Dust Storm as a quintessential big-city power player: ruthless, polished, and used to controlling every narrative in the room. Professionally, she is razor-sharp and highly competent; the entire scandal with Lillian Monroe shows how good she is at anticipating crises, crafting image, and thinking strategically under pressure.

The tragedy is that her competence is weaponized against her: she is scapegoated by her client, abandoned by her own firm, and dispatched to Texas under the guise of “business development.” This forced exile becomes the crucible that burns away the illusion of her old life. At first she clings to the trappings of that life—designer clothes in a dusty cabin, the gaudy engagement ring, the belief that success means staying in Manhattan no matter the cost—but the longer she’s on the ranch, the more her values shift.

Her defining trait is not actually ambition but protectiveness. Cassandra’s “bitch” persona is a shield she uses both professionally and emotionally, and Texas exposes how much of that armor hides a deep sense of responsibility and justice.

She defends Bree from sexist dress-code policing, teaches Gracie not to shoulder boys’ misbehavior, dismantles the powerful mayor when he tries to reduce her to eye candy, and stands up to Principal Beeker with meticulous legal and rhetorical precision. These moments show the core of who she is: someone who uses her skills to protect people who haven’t learned how to fight back yet.

That same protective instinct is what made her so effective with high-risk celebrity clients—and what made the Lillian situation so devastating, because she was betrayed by the very people she tried to save.

Emotionally, Cassandra’s arc is about shifting from performance to authenticity. In New York, her engagement to Tripp is mostly optics, a performance of “having it all” that never quite matches her private doubts.

The ring, the endless postponed wedding, and his constant prioritization of work or image over her feelings reflect a life where she is always a supporting act in someone else’s brand. At the ranch, she is forced into messy intimacy: living with Christian and his kids, dealing with cows and snakes, sharing bathrooms and kitchens and late-night porch talks.

She cannot curate her life there; the girls see her before coffee, Christian sees her vulnerable, and the family sees her fail and try again. By the time she mails back the engagement ring and quits her old firm, Cassandra has redefined success: not as status and optics, but as meaningful work, chosen family, and a love that actually shows up.

Romantically, she undergoes a shift in what intimacy means. Tripp’s neglect has left her convinced she is demanding or unlovable when she needs more than simple convenience.

Christian’s approach to domination in bed is a powerful reversal: he insists that control means prioritizing her pleasure and her trust, not erasing her. The book uses their sexual chemistry to underline a deeper emotional truth: Cassandra learns she is allowed to want, to take up space, and to be cherished rather than tolerated.

By the epilogue, when she stands as Christian’s partner, stepmother to the girls, and co-architect of the ranch’s new future, she isn’t a “reformed” city woman so much as a woman finally aligned with her own values—still sharp, still ambitious, but now using those traits in a life she deliberately chose.

Christian Griffith

Christian is introduced in Dust Storm as a widowed rancher and father, someone who carries both responsibility and grief like a second skin. His daily routine—making breakfast, braiding hair, juggling paperwork, worrying about bills and livestock—presents him as a man whose identity is built on caretaking.

He is reliable to an almost punishing degree, shouldering the ranch, his daughters, and the legacy of the Griffith name while quietly internalizing every misfortune as a personal failure. His suspicion of Cassandra and corporate “solutions” at the start is not simple narrow-mindedness, but the weariness of someone who has seen quick fixes come with strings attached and who knows that one mistake can ripple through generations of family land.

Underneath his gruff, practical exterior, Christian is intensely nurturing and observant. The way he defends Cassandra publicly when Jackson objectifies her, tells the ranch hands she carries the weight of his name, and insists they treat her like family, reveals his moral code: protection, respect, and loyalty.

He may not trust her expertise at first, but once he accepts her as part of his orbit, he will put his own authority behind her safety. The same protective instinct shapes his parenting.

He learns to curl Bree’s hair, negotiates Gracie’s school issues, and implements “five-day rules” for hairstyles because he has carefully studied what makes his girls feel secure. He is not a flawless saint; he can be controlling and stubborn, and his fear of losing people can translate into overprotective behavior.

But his rigidity comes from a place of fear, not arrogance, and Cassandra helps him differentiate between protecting his family and stifling them.

Christian’s emotional arc centers on guilt and letting go of the belief that he must personally absorb every blow life throws at the people he loves. Nate’s war injury, Gretchen’s death, failed crops, and finally Ray’s catastrophic bull-riding accident all feed into an unhealthy pattern: if he were just better, faster, stronger, maybe the bad things wouldn’t happen.

Cassandra’s steady presence at the hospital, her insistence that Ray’s injuries are not Christian’s fault, and her encouragement to consider therapy confront that narrative head-on. When he lists his three certainties—the sun will rise, Ray will wake up, and Cassandra will one day have his last name—he is not just making romantic promises; he is choosing hope and trust over fear and self-blame.

In love, Christian is both cautious and all-in. He genuinely tries to respect Cassandra’s engagement, telling himself he won’t cross that line even as the attraction between them grows.

When the dam finally breaks after the dress-code confrontation, his approach to sex reveals how he views power: he is physically dominant but emotionally careful, constantly checking in with her, tending to her afterward, and using that intimate space to show her a different model of partnership. His willingness to accept the massive redevelopment plan and bring in outside investors shows another growth point: he learns that true leadership can mean asking for help and trusting someone else’s expertise.

By the end of Dust Storm, Christian has not transformed into a new man so much as expanded into a fuller version of himself—still rooted, still responsible, but no longer trying to carry everything alone.

Bree Griffith

Bree, at thirteen, stands at a crossroads between childhood and adolescence, and Dust Storm uses her as a lens on how girls are policed and shaped by the adults around them. Early on, she is depicted as sensitive and eager to please: she adores her father, idolizes Cassandra’s glamour, and is easily rattled by authority figures like Principal Beeker.

The dress-code incident becomes a formative moment. Being told that her blouse is “distracting” and inappropriate because of her developing body threatens to embed shame and self-consciousness at an early age.

Instead, Cassandra and Christian together rewrite that script. Christian validates her truth and refuses to let the principal call her a liar; Cassandra challenges the sexualization of Bree’s body and frames the situation as an abuse of power rather than a failing in Bree.

This moment, and others like it, show Bree learning to navigate the conflicting expectations placed on young girls: to be modest but not prudish, confident but not “too much,” responsible but not taken advantage of. Cassandra becomes a crucial role model in this space, offering Bree an example of a woman who is unapologetically assertive.

Bree’s fascination with Cassandra’s clothes and hair gradually shifts from pure admiration of aesthetics to a deeper respect for her attitude and independence. At the same time, Bree’s love for Christian and her desire to protect her younger sister show that she has inherited the family’s loyalty and caretaking instinct.

By the epilogue, Bree’s relationship with Cassandra has evolved into a genuine stepmother–stepdaughter bond grounded in shared adventures and mutual respect. Their girls’ trip to New York, full of Broadway shows and shopping, becomes a merging of Cassandra’s old world with her new family.

Bree’s joking description of Cassandra as the “best evil stepmother” reveals how secure she now feels: she can play with the trope because it no longer threatens her. She is no longer simply Christian’s daughter watching adults make decisions over her head; she is an active participant in a family that listens to her and validates her experiences.

Gracie Griffith

Gracie, at eleven, brings a lighter, more chaotic energy to Dust Storm, yet she also represents another dimension of how young girls are socialized. Initially she seems like a classic younger sibling—chatty, imaginative, delighted by Cassandra’s sparkly presence, completely unfiltered when she tells Cassandra to “have a day as pretty as you are.” But the conversation about her science class, where she has been told it is her “job” to help Dylan focus, reveals how early girls are encouraged to manage and absorb the emotional labor of boys.

Cassandra’s fierce pushback, telling Gracie she is not responsible for Dylan’s behavior unless she is being paid to be his teacher or babysitter, gives Gracie language and permission to set boundaries. Her gleeful repetition of the idea that she’ll “let him run around on fire” if he chooses to be a problem is both funny and empowering.

Gracie’s relationship with Christian shows his gentlest side: he detangles her hair, negotiates pajama day logistics, and responds to her relentless chatter with patience. Her openness toward Cassandra helps smooth the stranger’s integration into their household; Gracie’s unfiltered affection breaks down some of Cassandra’s emotional defenses more quickly than any adult conversation could.

When Gracie and Bree both tell Cassandra “I love you,” Gracie is part of the emotional tipping point that solidifies Cassandra’s sense of belonging. Gracie’s acceptance is instinctive rather than deliberated; she loves Cassandra not because Cassandra proves herself on paper, but because she shows up, listens, and becomes part of their daily life.

Through Gracie, the novel highlights how environment can shape a child’s worldview. She is raised on a ranch where hard work and family loyalty are core values, but through Cassandra she also learns about personal autonomy, urban possibilities, and a broader sense of what women can be.

Gracie embodies the hope that the next generation will grow up with healthier boundaries and more expansive options than either Cassandra or Christian had in their youth.

Tripp Meyers

Tripp embodies the darker side of ambition and image management in Dust Storm. On the surface, he is everything Cassandra is supposed to want: a handsome, successful boss and fiancé in a prestigious New York firm, someone who can match her in ambition and status.

In reality, he is the personification of performance without substance. His abandonment of Cassandra at the ranch—leaving her in a dilapidated cabin with wildlife, driving off covered in manure, and then barely contacting her—sets the tone for his role in the story.

Work is his perpetual excuse, a shield he uses to avoid emotional accountability and to prioritize optics and client relationships over his partner.

The Lillian Monroe scandal crystallizes his moral bankruptcy. Tripp witnesses firsthand that Cassandra did her job correctly, but when her reputation comes under attack, he refuses to defend her because “it would look bad” for her fiancé to be the only one in her corner.

This choice reveals his core value: self-preservation and brand management over loyalty, truth, or basic decency. He not only fails to protect Cassandra; he actively benefits from her downfall by taking over Lillian as a client and jetting off to Spain.

Later, his arrest for embezzlement confirms that his disregard for ethical lines is systemic, not situational.

Tripp’s significance in the narrative goes beyond simple villainy; he is a mirror for who Cassandra might have become if she continued to prioritize image over integrity. Their engagement, with its endless delays and emphasis on how the ring “looks,” functions as a metaphor for a life built on optics.

Her ultimate decision to mail back the ring and resign from the firm is not just a breakup but a repudiation of the entire value system he represents. Tripp shows us what success without conscience looks like—and why Cassandra must walk away from it to find real happiness.

Lillian Monroe

Lillian Monroe, although not physically present in most of Dust Storm, exerts enormous influence over Cassandra’s life. As a high-profile actress with multiple DUIs, she is the kind of client Cassandra has built her career managing: volatile, fragile, but professionally valuable.

Cassandra’s efforts to secure a rehab deal, craft a sober public reentry, and control every detail of Lillian’s comeback demonstrate how far she will go to protect a client. Lillian’s drunken onstage tirade, accusing Cassandra of getting her drunk, paying off judges, and controlling her life, is both a professional catastrophe and a personal betrayal.

Lillian represents the way powerful systems—celebrity culture, media narratives, legal bargains—can weaponize a vulnerable but privileged person against the very professionals trying to help her. Whether Lillian consciously lies or genuinely misperceives events is almost beside the point; her words become truth in the public arena, and Cassandra’s reputation is destroyed.

Tripp’s decision to side with Lillian, taking over as her publicist, underscores how Lillian is not held accountable for her behavior in the same way Cassandra is. In the end, Lillian’s role is that of a catalyst: she exposes the fragility of Cassandra’s standing at the firm and forces Cassandra onto a path that eventually leads to the ranch.

Without Lillian’s meltdown, Cassandra might never have had the opportunity—or the push—to question whether her environment valued her as a person or just as a convenient shield.

Rebecca “Becks” Griffith

Becks is the bridge between Cassandra’s old world and Christian’s. As the pregnant sister-in-law whose family owns the ranch, she is both insider and critic of ranch life.

The flooding of Becks’s spare room is the logistical reason Cassandra ends up living with Christian, but Becks’s emotional role is much deeper. She quickly sees through Cassandra’s defenses and is one of the first to openly question whether Cassandra is truly happy with Tripp or merely performing happiness.

Her bluntness about wanting to hit Tripp with a dump truck is both comic and revealing—Becks has little patience for men who fail the women in her family.

In her interactions with Cassandra, Becks embodies a mixture of warmth, practicality, and mischievous insight. She recognizes the chemistry between Christian and Cassandra long before they are willing to name it, and her amused reaction when Christian cages Cassandra between his arms in the office doorframe shows that she is watching their slow-burn romance with interest.

Becks is also a reminder that rural women are not simple caricatures: she is managing pregnancy, family, and the demands of ranch life while still making time to walk five miles to try to induce labor and to nudge Cassandra toward self-reflection. She helps normalize the idea that ambition, motherhood, and partnership can coexist in varied forms.

Silas Griffith

Silas, the ranch patriarch, represents the older generation’s commitment to land, legacy, and family reputation in Dust Storm. He initially seems like a traditional authority figure, the one who has long carried responsibility for the ranch’s survival.

When Tripp arrives with his corporate mindset and disdain for the rural setting, Silas’s choice to direct business questions to Christian signals a deliberate transfer of authority: he trusts his son to lead and wants others to recognize that leadership. This is a quiet but powerful vote of confidence in Christian.

Silas’s attitude toward Cassandra is also instructive. He never dismisses her outright, even though he might be skeptical about what a New York publicist can offer a cattle ranch.

Instead, he lets the younger generation test new ideas while remaining a steady presence in the background. In the face of Ray’s catastrophic injury, Silas becomes part of the family’s support network, participating in hospital rotations and the eventual plan to bring Ray home with full-time care.

He represents the continuity that allows the Griffith family to absorb shocks and keep going, even as the ranch evolves into something new.

Nate Griffith

Nate, one of Christian’s brothers, is more in the periphery of Dust Storm, but his presence helps flesh out the family’s history of sacrifice and trauma. He is a veteran with war injuries, and Christian’s guilt over what happened to Nate feeds into his broader pattern of internalizing every bad outcome as his personal responsibility.

Nate’s experience underscores the theme that danger and loss are not confined to the ranch; they are woven into the family’s past on multiple fronts.

In lighter moments, Nate participates in the teasing and gossip that swirl around Christian and Cassandra, especially when Christian shows up in town with a woman in his truck. This combination of camaraderie and history makes Nate part of the emotional fabric that Cassandra chooses when she decides to stay.

The Griffith brothers are not interchangeable; each has his own history and scars, and Nate’s particular mix of injury and humor contributes to the sense that this is a real, lived-in family rather than a backdrop for romance.

Carson “CJ” Griffith

CJ serves primarily as a foil to some of the more risk-tolerant members of the family and to the ambitious redevelopment project Cassandra proposes. He is the brother most likely to resist outside investors and large-scale changes, reflecting a cautious, perhaps skeptical perspective on growth.

His anticipated dislike of bringing in Lawson International shows a legitimate fear many family businesses have: that corporate money will erode their independence and cultural identity.

CJ’s presence in Dust Storm gives weight to the internal debates about the ranch’s future. The novel does not present Christian and Cassandra’s vision as unanimously celebrated; instead, CJ reminds readers that not everyone in a community wants or benefits from the same kind of progress.

By engaging with his resistance, the story acknowledges that modernization is complex and that even positive change can be painful for those who worry about what might be lost.

Ray Griffith

Ray is the dramatic embodiment of the risks that come with the ranch-adjacent lifestyle. As the tattooed, “Funcle Ray” bull rider, he brings chaotic humor and danger into the story.

Early on, his tradition of letting Bree and Gracie color in his tattoos with markers illustrates his role as the fun uncle who offers the girls a different kind of adult presence: less structured, more rebellious, but still deeply loving. His easy banter with Cassandra and acceptance of her into the family circle signal his openness and charm.

The bull-riding accident upends this dynamic and becomes one of the novel’s most intense emotional pivots. Ray’s brutal injuries—spinal damage, broken ribs, internal bleeding—and the likelihood of permanent paralysis force the entire family to confront the limits of bravery and the price of risk.

For Christian, Ray’s near-death experience amplifies old guilt; for Cassandra, it is a test of whether she will truly integrate into the family or retreat to the safety of distance. Her choice to run ranch operations, manage the girls’ routines, and show up daily at the hospital marks her as indispensable.

Ray’s eventual awakening and the reveal that he won the championship with a 91.9 score provide bittersweet triumph. He has achieved his dream but at an enormous cost.

His anger, grief, and long recovery are not glossed over, and the family’s decision to bring him home with full-time care reinforces the novel’s emphasis on communal responsibility. Ray’s arc underscores that love sometimes means accepting a future radically different from the one you imagined and that heroism can look like surviving and adapting, not just riding the meanest bull.

Gretchen Griffith

Gretchen, Christian’s late wife, is a ghostly but important presence in Dust Storm. She appears only in memories and photographs, yet her absence shapes much of Christian’s behavior.

The careful routines he maintains with his daughters, his reluctance to risk his heart again, and his compounded guilt over every subsequent tragedy are rooted in the loss of Gretchen. When Cassandra notices her in family photos and Christian acknowledges her death plainly, the book invites both Cassandra and the reader to understand that he is not an untouched bachelor but a widower who has already endured profound grief.

Gretchen’s memory also influences the girls, even if indirectly. The way they cling to Christian, the family’s emphasis on stability, and the significance of Cassandra stepping into a maternal role are all colored by the fact that they once had a mother who is gone.

The narrative is careful not to frame Cassandra as a replacement but as a new chapter; Gretchen’s existence does not diminish Cassandra’s importance, nor does Cassandra’s presence erase Gretchen. Instead, Gretchen’s role is to highlight that love can exist more than once in a life, and that moving forward does not dishonor what came before.

Claire Griffith

Christian’s mother, later named as Claire, is part of the quiet backbone of the Griffith family in Dust Storm. She is the one who helps with school runs, who shows up to support Christian and the girls, and who participates in the extended rotations at the hospital after Ray’s accident.

Her suggestion that Cassandra stay in Christian’s spare room is one of the practical decisions that push Cassandra deeper into the family’s daily life, accelerating the intimacy that eventually leads to romance.

Claire represents generational continuity and the strength of matriarchs in rural families. She does not dominate scenes with dramatic speeches; instead, she contributes through consistent presence and practical solutions.

Her willingness to treat Cassandra as someone who belongs, from early dinners to crisis logistics, makes a powerful statement about inclusion. By the time Christian lists Cassandra and Claire as family for ICU access, the reader understands that Cassandra has been woven into the same circle of trust and care that Claire anchors.

Jackson

Jackson, the ranch hand who crudely objectifies Cassandra, serves as a localized embodiment of misogyny and entitlement within the workplace. His comments about Cassandra being the reason they cannot get raises reduce her to a scapegoat and sexual object, ignoring both her expertise and her humanity.

The confrontation Christian stages—grabbing Jackson by the shirt, publicly asking if he would talk that way about Christian’s daughters or mother, and making it clear that Cassandra carries the weight of the Griffith name—turns Jackson into a teaching moment for the entire crew.

Jackson’s role in Dust Storm is to highlight the gap between the ranch’s stated values and the behavior of some of its workers. By making Cassandra’s status explicit and tying it to consequences (Jackson will be fired if she wants him gone), Christian sends a message that the old boys’ club mentality is no longer acceptable.

Jackson may be one man, but the scene around him marks a turning point in how the ranch as a workplace will function under Christian and Cassandra’s joint leadership.

Principal Beeker

Principal Beeker is one of the most overtly antagonistic figures in Dust Storm, not because she is violent or criminal but because she uses institutional power to shame and control a teenage girl. Her dress-code enforcement against Bree, framed as protecting boys from distraction due to Bree’s “developed womanly features,” reveals a deeply ingrained bias that polices girls’ bodies instead of boys’ behavior.

She attempts to frame Bree as dishonest, suggests she changed clothes at school, and asserts the right to “interpret” dress-code guidelines based on her personal judgments.

Cassandra’s methodical dismantling of Beeker—recording the conversation under Texas one-party consent laws, explicitly labeling the behavior as sexualization of a minor, and threatening to escalate the issue to the school board and even into politics—turns Beeker into a case study in accountability. Beeker’s eventual retreat and Bree’s return to class show that institutional bullying can be confronted when someone is willing and able to challenge it.

Beeker’s early retirement, implied later through the mayor’s reference, marks a small but significant victory against the everyday injustices that shape young girls’ experiences.

Mayor Charles Getty

Mayor Getty appears in Dust Storm as a polished local power broker, more concerned with image and gossip than with ethical leadership. When he approaches Cassandra at the ranch gate, fishing for information about the Griffiths’ plans and implying that she is just something “nice to look at,” he underestimates both her intelligence and her capacity for retaliation.

Cassandra’s quick deduction of his affair—lipstick on his collar, the scent of a local woman’s perfume—and her promise to force him into public support for the groundbreaking ceremony reveal how vulnerable he really is to the same kind of narrative manipulation she used to deploy in New York politics.

Getty’s role underscores one of the book’s recurring themes: corruption and hypocrisy are not confined to big-city elites. Small towns have their own power games and secrets, and Cassandra’s skills translate seamlessly into this environment.

By compelling the mayor to attend and publicly back the ranch’s redevelopment, she not only punishes his sexism but also secures political cover for the Griffiths’ ambitious future. Getty is a reminder that local politics and personal morality often clash, and that someone like Cassandra can tilt that balance when she is on the side of those she cares about.

Mike and the Carrington Group

Mike, Cassandra’s boss at the firm, and the Carrington Group overall stand in for corporate culture in Dust Storm. Mike’s treatment of Cassandra after the Lillian scandal—offering the “choice” between taking the Texas assignment or being fired—shows how little loyalty or justice exists in that world.

The firm is more concerned with appeasing a volatile celebrity and protecting its own reputation than with investigating the truth of Cassandra’s actions. Mike embodies a managerial style that dresses up punishment as opportunity, repackaging exile as “business development” and hoping Cassandra will be grateful.

When Cassandra finally calls Mike from the ranch, submits the final projections, and then resigns, it is a pivotal act of self-definition. She is no longer willing to be the firm’s shield or scapegoat, nor is she willing to trade her integrity for proximity to power.

Mike’s presence in the story emphasizes what Cassandra is giving up: not just a job but an entire network of influence and prestige. Her willingness to walk away from that environment underscores the depth of her transformation and reinforces the idea that true power comes from choosing your own values, not from clinging to toxic institutions.

The Ranch Animals: Sadie and Mickey

Although not human, Sadie the Australian shepherd and Mickey the cow function as minor but memorable characters in Dust Storm, shaping Cassandra’s early experience of ranch life. Sadie is Christian’s unexpected weapon against Cassandra’s desire to sleep in, barreling into the bedroom and jumping on her until she gets out of bed.

This scene is comedic but also symbolic: on the ranch, life does not conform to Cassandra’s preferred nine-to-five schedule. Sadie embodies the relentless, chaotic energy of the environment Cassandra must adapt to, and her immediate obedience to Christian’s whistle also reinforces his quiet authority.

Mickey, Gracie’s beloved cow with pool noodles on his horns, is a gentler form of chaos. His presence in the cabin, on the office couch, and even on the porch during a charged romantic moment constantly undermines Cassandra’s attempts at control and composure.

He is a walking reminder that this is a working cattle ranch, not a curated PR event, and that real life here will never fully bend to her aesthetic standards. Together, Sadie and Mickey soften the tone of the book, adding humor and warmth while symbolizing the unruly, living reality of the world Cassandra ultimately chooses to call home.

Themes

Reinvention and Self-Definition

Cassandra’s story in Dust Storm runs on the engine of reinvention, but not the glossy kind she sells as a publicist. At the beginning, her life is built on image management: curated clients, a picture-perfect engagement, the “right” ring, the right job title, the right New York address.

When Lillian’s public meltdown destroys her reputation, she is pushed into a kind of forced exile rather than a glamorous brand refresh. Texas is framed as punishment, a dumping ground for liabilities, yet it becomes the setting where Cassandra finally asks who she is when there is no red carpet, no firm, and no fiancé using her as a prop.

The early days at the ranch show her clinging to old markers of identity: designer clothes in the dust, horror at snakes and cows, demands for WiFi and a landline as though connection to Manhattan will keep her real life intact. Over time, the book follows how those markers lose their grip.

Her worth stops being tied to Tripp’s approval or the firm’s metrics and starts tying itself to things that feel quietly radical for her: a teenager looking at her with real admiration, a widowed father trusting her with his children, a ranch family listening seriously to her ideas. Reinvention here is not a makeover montage but a series of choices where Cassandra stops performing “successful woman” for an audience and starts living it on her own terms.

When she resigns from her firm, it is not just a career pivot; it is a rejection of fear-based decision-making. By the time she returns from New York as a Texas resident running operations and sharing a home with Christian and the girls, her identity is no longer a branding exercise.

It is grounded in competence, affection, and a willingness to risk vulnerability instead of constantly protecting the façade that once defined her.

Power, Reputation, and Who Controls the Story

From the first red-carpet ambush, Dust Storm is obsessed with who gets to tell the story and how power operates through narrative. Cassandra’s professional life has been built on controlling perception: crafting statements, redirecting scandals, negotiating deals that keep destructive truth just manageable enough to preserve careers.

Lillian’s live tirade shatters her illusion that skill alone can protect her; the actress’s lies go viral while Cassandra’s careful work evaporates, and the firm chooses the more profitable narrative over the true one. Tripp’s refusal to defend her in that meeting, despite knowing the facts, shows how power aligns with whoever brings more leverage, not whoever is right.

Exiled to Texas, Cassandra initially views the ranch as a new “project” to spin into something profitable for distant investors. Yet the ranch environment forces her to confront power on a smaller, more intimate scale.

She recognizes the same dynamics of control and narrative in the school’s dress code incident: a principal labeling Bree “distracting” and then insisting on her authority to “interpret” rules. Cassandra’s recording of that meeting and sharp use of Texas law turn the tables, using the tools of PR not for celebrity damage control but to protect a child from institutional humiliation.

Her confrontation with Mayor Getty shows again how she wields information like a weapon, exposing his hypocrisy and forcing him to behave publicly in ways that align with the ranch’s goals. The crucial shift is that she stops using narrative tools to prop up entitled people like Tripp and starts using them to defend vulnerable people and build something communal.

By the end, when she gives the groundbreaking speech and frames the Griffith project as a shared future between family, community, and investors, the story is finally hers to shape. Her name, once synonymous with scandal, becomes attached to a tangible, hopeful venture, showing that power in this world lies not just in who speaks loudest, but in who is willing to speak for the right reasons.

City and Country, Class Clash, and Respect

The contrast between Cassandra’s Manhattan life and Christian’s Texas ranch is more than aesthetic; it exposes class assumptions and different value systems. At first, Cassandra views the ranch through the lens of inconvenience and hazard: no decent office, no reliable internet, wild animals occupying cabins, and a wardrobe utterly unsuited to manure and fire ants.

Christian, meanwhile, looks at her as a high-maintenance outsider imposed on him by distant people who neither understand nor respect the demands of the land. Tripp embodies the worst of urban condescension, treating the ranch like a primitive inconvenience while tracking flights on his phone and using “deliverables” language on a porch where boots and mud tell a different story about what work means.

His fall into manure and scramble for cell reception functions as a sharp comic image of a worldview collapsing under real-world conditions. As Cassandra spends time on the ranch, the book traces how her assumptions about rural life begin to shift.

She sees the complexity of Christian’s responsibilities: veterinary emergencies, financial juggling, staff management, and the emotional weight of keeping multigenerational land afloat. The ranch is not some quaint backdrop; it is a demanding enterprise that requires intelligence and constant adaptation.

At the same time, she brings a new perspective that the Griffith family needs: the ability to translate their strengths into sustainable revenue streams, to negotiate with investors, and to confront small-town power structures that would rather keep them boxed in. The class clash gradually transforms into mutual respect.

Cassandra learns that sophistication is not measured by zip code, and Christian realizes that corporate skills and strategic thinking can coexist with calloused hands and early mornings. The final vision of a luxury lodge, equine programs, and community-focused facilities sitting on land that still functions as a family ranch embodies a reconciliation of those worlds.

Rather than one side conquering the other, city and country create a hybrid life where espresso, Broadway trips, and cattle drives can all belong to the same story.

Family, Care, and Chosen Belonging

Family in Dust Storm is loud, complicated, and constantly present, whether Cassandra wants it or not. Christian’s household is a whirlwind of school runs, dance classes, tangled hair, grieving hearts, and ranch obligations.

From the moment Bree and Gracie barrel into the story, Cassandra is pulled into a web of relationships that do not respect the professional distance she is used to maintaining. Initially, she keeps insisting she is “just there to work,” but everyday domestic scenes chip away at that claim: watching Christian carefully curl Bree’s hair, seeing Gracie light up at a simple compliment, noticing how the Griffith siblings tease and support one another at family dinners.

The ranch presents a form of care that is unpolished but relentless; everyone shows up for births, emergencies, meals, and later for Ray’s catastrophic injury. Cassandra, who has built her life around high-functioning independence, is both unnerved and drawn to this environment where people assume they will be part of each other’s problems.

Her shift from guest to family member happens almost by stealth. She starts by offering advice about school politics and gender expectations, then takes a more hands-on role during the hospital rotation, managing schedules, finances, and child care when everyone else is exhausted.

The moment Bree and Gracie tell her they love her and she says it back marks a deeper commitment than any professional contract. The novel suggests that belonging is less about legal titles and more about consistent presence: who shows up at the hospital with food, who braids hair at seven in the morning, who answers panicked phone calls.

By the time Christian lists her as family at the hospital and gives her a jacket with the ranch logo, that belonging has been formalized in both paperwork and daily habit. The final proposal does not create the family; it confirms a structure of care that has already formed around shared responsibility, affection, and the conscious choice to stay even when things are hard and messy.

Gender, Misogyny, and Bodily Autonomy

Across its romantic and comedic surface, Dust Storm keeps returning to the ways women’s bodies and behavior are policed, dismissed, or exploited—and how Cassandra refuses to let that stand, even when she underestimates her own worth. Lillian’s meltdown is rooted in a warped power dynamic where a troubled actress can rewrite history by painting Cassandra as a sinister handler who starves, controls, and manipulates her body and image.

The public is quick to believe the narrative of a ruthless female publicist abusing another woman, exposing how easily misogynistic stereotypes attach themselves to successful women in power. Cassandra loses her career standing not because she did anything wrong, but because her existence as a sharp, uncompromising professional makes her an easy villain.

On the ranch, similar dynamics play out in more intimate settings. Principal Beeker’s treatment of Bree is a textbook example of how institutions sexualize girls and burden them with responsibility for male distraction.

The accusation that Bree’s blouse is “too low” even when it fits the dress code places blame on a thirteen-year-old’s developing body instead of on boys or teachers who choose to objectify her. Cassandra’s furious, strategic defense of Bree reframes the issue: the problem is not the child’s neckline but the adult’s gaze and misuse of authority.

Her conversation with Gracie about Dylan in science class carries the same message in a subtler form—girls are not default caregivers for disruptive boys, and their emotional labor is not owed just because someone else cannot manage themselves. Cassandra also confronts sexual objectification among the ranch hands when Jackson talks about her in crude terms; Christian’s public defense, explicitly linking her respect to that of his daughters and mother, reinforces that women’s value is not negotiable based on who they are to men.

Even in her sexual relationship with Christian, questions of autonomy and respect are central. His dominance is framed not as control over her body but as an earned trust to prioritize her pleasure and boundaries, a corrective to earlier partners and to a fiancé who treated her body like another piece of his professional image.

Grief, Guilt, and the Work of Healing

Christian’s calm competence hides a long trail of grief and survivor’s guilt, and Dust Storm repeatedly brings these buried wounds to the surface. The loss of his wife left him a single parent to two young girls, forcing him to absorb both parental roles while still running a demanding ranch.

Nate’s war injury adds another layer of “what if I had done more,” and the unpredictable disasters of ranch life—failed crops, medical emergencies with livestock, financial strain—train him to assume that everything that goes wrong is somehow his fault. Cassandra arrives in the middle of this emotional terrain and gradually learns to read the signs: the way he mutters about always waiting for the next bad thing, the way he shoulders responsibility for every crisis.

Ray’s bull-riding accident intensifies this pattern into something almost unbearable. Watching his brother crushed in the arena and then lying in a hospital bed with catastrophic injuries triggers a spiral of self-blame.

Christian sees Ray’s profession, their family culture around risk, and even the timing of events as things he should have prevented. The book treats healing not as a dramatic single revelation but as a series of conversations, small acts of care, and steady presence.

Cassandra’s role in this process is less about magical comfort and more about refusing to let his guilt go unchallenged. She makes him eat when he is running on adrenaline, forces him to sit and walk instead of pacing himself into collapse, and uses her own experience of having her life shredded by forces outside her control to argue that loving someone does not make you responsible for every way they can be hurt.

Therapy is mentioned, not as a punchline but as a practical tool, and Christian’s willingness to talk about his feelings in front of Cassandra shows progress from stoic isolation to shared burden. Ray’s ultimate survival as a quadriplegic underlines that healing is not about restoring things to how they were, but about learning to live in a changed reality without letting guilt dictate every decision.

Love as Partnership, Not Performance

The contrast between Cassandra’s relationship with Tripp and her partnership with Christian forms one of the clearest emotional arcs in Dust Storm. Tripp represents a love that looks impressive from the outside: a powerful boss-turned-fiancé, a ring chosen for “optics,” an engagement that fits seamlessly into society pages and investor meetings.

Yet every detail of that relationship reveals hollowness. He fails to show up for a courthouse wedding he himself suggested, abandons her at the ranch without basic courtesy, refuses to defend her when her career is on the line, and treats her exile as a minor scheduling inconvenience while he wines and dines her former client in Spain.

Their intimacy has withered to the point where distance and excuses stand in for actual connection. Cassandra initially clings to this relationship because it symbolizes safety and status, not because it offers genuine emotional support.

Christian offers a starkly different model. His affection is expressed through daily actions rather than grand gestures: teaching her to ride, paying for her nails and boots without making her feel indebted, defending her in front of his workers, trusting her with major financial and strategic decisions.

When he does make a dramatic move—such as telling her she can either undress him or walk away from their mutual attraction—it comes with clarity and a commitment to her consent, not manipulation. Sex between them becomes a space where she can rewrite narratives about her desirability and worth; he listens to her insecurities and frames dominance as a responsibility to prioritize her needs.

Their emotional partnership deepens through crisis rather than collapsing under it. The hospital weeks show them dividing roles, sharing fears, and acknowledging dependence.

By the time Christian tells her that one day she will have his last name, it is not a claim of ownership but a statement of intention grounded in everything they have already survived together. Her choice to resign from her job, move to Texas permanently, and accept his proposal at the future lodge site marks love not as a prize she won, but as a mutual decision to build a life that honors both their strengths and vulnerabilities.

Community, Risk, and Building a Shared Future

The development project at the heart of Dust Storm transforms the ranch from a private family struggle into a focal point for the broader community’s hopes, fears, and gossip. At first, the Griffith ranch is simply trying to stay afloat: aging infrastructure, unreliable revenue streams, and internal disagreements about how much change is acceptable.

Cassandra’s initial revenue plan is sensible but cautious, and Christian’s refusal of that “not big enough” version pushes the story into a larger conversation about risk. Accepting Lawson’s ten-million-dollar investment ties the family’s future to corporate interests that could easily undermine them if mishandled.

The book tracks their attempt to navigate this tension, balancing ambition with a refusal to become a hollow tourist spectacle. Cassandra positions the lodge, restaurant, and equine programs as extensions of what the ranch already represents rather than replacements for it.

Community interactions reinforce that this is not just about the Griffiths. The mayor, the principal, local businesses, and even the nail salon staff all respond to rumors and changes, reacting with skepticism, curiosity, or opportunism.

The groundbreaking event stands as a symbolic turning point: the tent, the freshly painted fences, the gathered investors and townspeople all signal that the ranch’s future is now publicly shared. Cassandra’s decision to resign from her firm right after this event shows that she understands the stakes; she is not just consulting on a project but tying her livelihood and identity to this place and its people.

Ray’s accident and the hospital rotation make clear that the community they are building is not only economic but relational, dependent on networks of care, time, and labour. By the epilogue, when Cassandra rides with Christian to the marked lodge foundation and agrees to marry him there, the risk has transformed into commitment.

The future they are constructing is not guaranteed, but it belongs to them, to the girls, and to the wider circle that has watched the ranch change. The novel closes on the idea that shared risk—financial, emotional, physical—is the price of a meaningful communal future, and that stepping into that risk together is itself an act of hope.