Eleanore of Avignon Summary, Characters and Themes

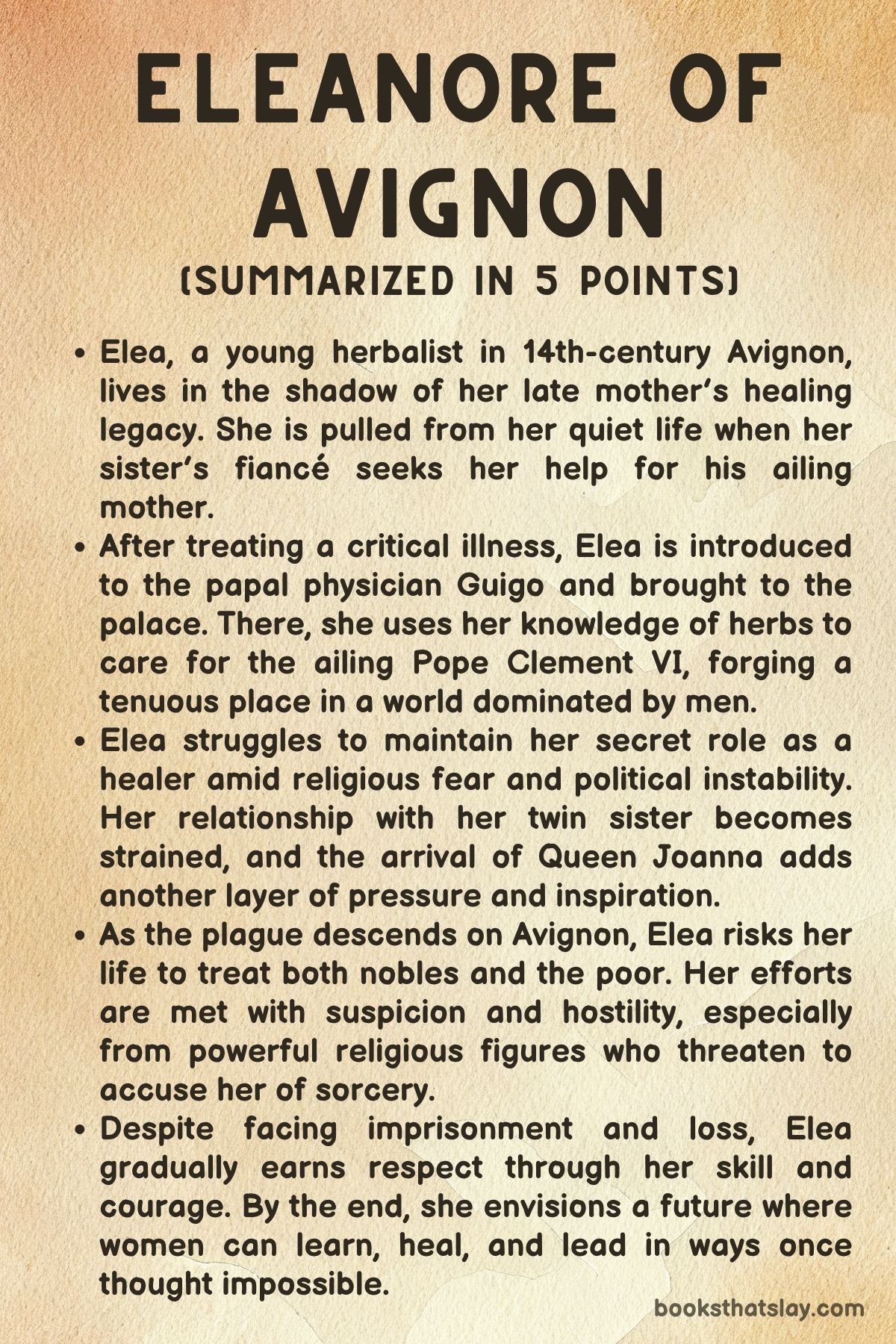

Eleanore of Avignon by Elizabeth DeLozier is a richly imagined historical novel set against the backdrop of 14th-century Avignon at the dawn of the Black Death. The story follows Eleonora Blanchet, a gifted herbalist and daughter of a martyred midwife, as she navigates a world of patriarchal power, religious intolerance, and medical upheaval.

Torn between duty and personal longing, Eleonora’s journey blends scientific curiosity, spiritual resilience, and the complexities of love in a society gripped by plague and fear. DeLozier’s narrative balances emotional intimacy with sweeping historical detail, giving readers an immersive look at the trials and transformations of a woman ahead of her time.

Summary

In the year 1347, in the walled city of Avignon, Eleonora Blanchet lives in the shadow of her late mother Bietriz—a skilled midwife and herbalist who died in disgrace, condemned as a witch by the Church. Eleonora, or Elea, inherits her mother’s talents but not her recognition.

Haunted by grief, guilt, and an unresolved rift with her twin sister Margot, Elea leads a life of quiet survival. Her world begins to shift the day she rescues a wounded dog from the forest, naming him Baldoin and forming a bond that rekindles memories of her mother’s affinity for animals.

Tensions mount in Elea’s family as Margot prepares to marry Erec Dupont, a wealthy suitor whose mother, Mathilde, once betrayed Bietriz. Elea is summoned to treat Mathilde, whose condition has deteriorated due to negligent care.

Using her mother’s remedies, Elea manages to stabilize her, but Mathilde, in a delirious state, accuses Elea of murder. The encounter reignites Elea’s anger and solidifies her distrust of the Duponts.

Meanwhile, the streets of Avignon erupt in hysteria with the arrival of flagellants led by Father Loup—the same priest who denied Bietriz her last rites.

Amid rising tensions, Elea meets a stranger in the forest: a physician named Guigo, later revealed to be Guy de Chauliac, the pope’s medical advisor. He is struck by her herbal knowledge and invites her to the papal palace.

There, Elea discovers her patient is none other than Pope Clement VI. Despite her lack of formal training, she administers a tonic passed down from her mother, offering him temporary relief.

Guigo, initially skeptical, agrees to mentor her, and Elea becomes his apprentice.

As Elea immerses herself in professional medicine, her skills grow. She diagnoses ailments missed by others, treats conditions from minor skin infections to kidney issues, and even participates in a pig dissection—a substitute for human autopsy banned by the Church.

Guigo grows to respect her intuitive grasp of anatomy and care. The looming threat of plague becomes real when reports confirm its arrival in Marseille.

The city braces for devastation.

Back home, Elea’s relationship with Margot deteriorates. Erec’s family collapses into financial ruin, ending the engagement.

Elea offers comfort, but their bond remains strained. At court, Queen Joanna is exonerated in a controversial trial for her husband’s murder and soon requires a midwife.

Elea is appointed, entering a world of royal rituals and political games. There, she befriends Paolo, a witty musician, and navigates the queen’s complex moods.

As the plague’s second form devastates Avignon, Elea splits her time between court duties and plague work. A critical moment arises when David, the Jewish nephew of a doctor, contracts the disease and volunteers for an experimental surgery.

Elea assists in the high-risk operation, which succeeds—an unexpected glimmer of hope. Her bond with David deepens into a quiet romance, but their relationship is forbidden and dangerous.

Margot warns her of the risks, especially with Father Loup stoking anti-Semitic fears.

Despite the emotional weight, Elea pushes forward. She dissects the corpse of Mathilde, confronting her past and doubts.

Overwhelmed by guilt and fear, she briefly flees her duties but returns with renewed purpose, empowered by her mother’s memory and her own moral compass. As Queen Joanna nears childbirth, Elea negotiates to continue her plague work.

Joanna, moved by Elea’s appeal to maternal duty, agrees.

Peace returns briefly after Elea successfully delivers the queen’s daughter, Princess Catherine. She also helps nurse Guigo through the plague, deepening their mutual respect.

David confesses his love and invites her to flee to Granada, but Elea declines, tethered by duty to her city and sister. Joanna offers her a position in Naples, which she also declines, choosing purpose over prestige.

The queen sends her generous parting gifts in gratitude.

Tragedy strikes when Elea is tricked into leaving the palace and captured by Father Loup. Framed for witchcraft using her medical notes and drawings, she is publicly humiliated and sentenced to death.

In her prison cell, she dreams of her family and prepares to die. But salvation arrives in the form of Paolo and Brother Remy, who, along with Guigo and others, orchestrate a daring rescue.

During their escape, Elea learns the final and most devastating truth: Margot, dying of plague, willingly took her sister’s place at the stake to protect her. Margot’s selfless sacrifice breaks Elea’s heart and becomes the spiritual climax of her journey.

The novel closes with Elea aboard a ship bound for Granada, accompanied by David. Though scarred by loss and grief, she moves forward with a sense of fragile hope.

A letter from Guigo expresses his healing and longing for her return. Margot’s final words—“You are myself”—linger as a haunting and loving echo of the bond that shaped Elea’s destiny.

Through pain and persecution, Elea emerges not just as a healer, but as a survivor. She embodies the fusion of science and empathy, resilience and love, in a world struggling to reconcile old superstitions with emerging knowledge.

Eleanore of Avignon is a powerful testament to the courage of women who fight to heal in a world that would rather see them silenced.

Characters

Eleanore Blanchet

Eleanore Blanchet emerges as the soul of Eleanore of Avignon, a woman whose journey from herbalist to political and medical savior is shaped by trauma, resilience, and conviction. Deeply rooted in the teachings of her mother Bietriz, Elea channels a generational wisdom of healing, using knowledge that society often associates with witchcraft.

Her early struggles center on familial tensions, particularly with her twin sister Margot, and a deep-seated mistrust of the Dupont family—emotions that intensify when she treats Mathilde Dupont, the very woman who once betrayed her mother. Eleanore’s dual commitment to science and compassion is further tested when she accepts Guigo’s invitation to treat the gravely ill Pope Clement VI, revealing her innate diagnostic brilliance and instinctual healing.

Despite lacking formal education, she quickly adapts, mastering anatomy and medicinal practice through sheer will and observational acuity. As the plague descends upon Avignon, Elea straddles two worlds—the gilded halls of Queen Joanna’s court and the bloody, fetid plague wards—never losing her moral compass or her empathetic touch.

Her romantic entanglement with David, a Jewish man, becomes a symbol of defiance in a time of prejudice and spiritual panic. Ultimately, Eleanore’s arc is one of sacrificial growth, culminating in false accusations of witchcraft, imprisonment, and near execution.

Yet she survives due to loyalty from allies and the love of her sister, whose death scars her. Eleanore’s legacy is that of a woman who, in choosing healing over vengeance and duty over comfort, rises to embody the essence of strength in a collapsing world.

Margot Blanchet

Margot, Eleanore’s twin sister, is portrayed as a tragic foil—defined not by her lack of strength but by how differently that strength manifests. Early on, Margot chooses conformity and societal security, aligning herself with Erec Dupont and seeking stability through marriage.

Her relationship with Elea is marred by resentment, emotional distance, and conflicting worldviews, particularly regarding their mother’s memory and the dark legacy of the Duponts. Margot’s judgment of Elea’s relationship with David—rooted in fear more than hatred—illustrates the constraints placed upon women who choose survival over idealism.

Yet, as the story unfolds, Margot transforms in quiet but profound ways. After her engagement dissolves, she begins to comprehend the cost of compromise, and her emotional rigidity softens.

Her final act—taking Elea’s place on the pyre—is the ultimate gesture of love, sacrifice, and absolution. In that selfless moment, Margot not only redeems their fractured bond but also elevates herself as one of the novel’s most heroic figures.

Her death, though heart-wrenching, is not in vain; it leaves behind a spiritual imprint that reshapes Elea’s understanding of familial love and resilience.

Guigo de Chauliac

Guigo, later revealed as the famed physician Guy de Chauliac, represents the tension between empirical science and inherited folk knowledge. Initially appearing enigmatic and cautious, he becomes one of Eleanore’s greatest mentors and defenders.

What makes Guigo compelling is not just his medical brilliance but his capacity to evolve—he begins with skepticism toward Elea’s untrained methods but grows to respect her intuition and learn from her. Their professional partnership is defined by mutual admiration, intellectual synergy, and emotional complexity.

Guigo’s quiet advocacy, whether in dissecting pigs to teach anatomy or fighting to save the Pope, reinforces his role as both educator and ally. Even after Elea’s escape, his letters reveal a continued emotional attachment, tinged with paternal warmth and collegial pride.

Guigo’s presence anchors the novel in the broader history of medical transformation, bridging superstition and science in a time of societal collapse.

Queen Joanna of Naples

Queen Joanna, both controversial and charismatic, is portrayed as a figure of political intrigue, emotional volatility, and hidden strength. Her trial for her husband’s murder exposes the duality of public perception and private anguish—she wins acquittal not through innocence, but through persuasive power.

Joanna’s relationship with Elea is initially transactional, but it deepens into a complex mentorship fraught with jealousy, admiration, and strategic manipulation. While she can be capricious and demanding, Joanna reveals a core of maternal resolve and political acumen.

Her eventual acceptance of Elea’s dual responsibilities reflects a buried empathy and acknowledgment of their shared burdens as women in patriarchal systems. Joanna’s arc concludes with a gesture of magnanimity, offering Elea title and reward, demonstrating her capacity for generosity and transformation.

She is not a moral figurehead, but rather a survivor, navigating a treacherous court with grace and steel.

David Farissol

David, the Jewish nephew of Dr. Farissol, functions as both Elea’s love interest and moral compass.

Intelligent, kind, and brave, David’s role expands far beyond romantic subplot. As a plague patient who volunteers for an experimental procedure, he embodies the novel’s theme of sacrifice in the name of knowledge.

His relationship with Elea is tender yet subversive, crossing religious and social boundaries in a climate of growing intolerance. David is fully aware of the risks but pursues both science and love with unwavering integrity.

His proposal to Elea—to flee together to Granada—offers a glimpse into a possible utopia, but Elea’s refusal and his understanding response highlight the maturity of their bond. His final presence beside her on the ship represents more than escape; it signifies hope, renewal, and the merging of intellect with compassion.

Father Loup

Father Loup is the novel’s embodiment of fanaticism, patriarchal oppression, and religious hypocrisy. From the moment he refuses Bietriz last rites, he casts a shadow over Elea’s life.

Loup’s resurgence during the plague—spearheading flagellant movements and inciting public hysteria—demonstrates how spiritual zeal can be weaponized. His targeting of Elea, manipulation of her writings, and orchestration of her public humiliation and near execution reveal the chilling power of institutionalized misogyny.

Loup does not merely fear Elea’s intellect—he seeks to extinguish it. His eventual failure, countered by the solidarity of allies like Paolo and Remy, underscores the strength of community against tyranny.

Though defeated, his impact lingers as a reminder of the cost of silence and the importance of resistance.

Mathilde Dupont

Mathilde is a haunting figure whose decline parallels the collapse of old social orders. Once the symbol of betrayal and oppression—instrumental in Bietriz’s downfall—she is found deranged and physically decaying when Elea is called to treat her.

The encounter is as much exorcism as it is medical intervention. In her delusions, Mathilde confuses Elea for Bietriz and confesses imagined crimes, allowing Elea to confront her mother’s ghost, both literally and metaphorically.

Her later autopsy becomes a pivotal moment in Elea’s medical and emotional development, symbolizing the reclaiming of agency from a legacy of guilt and shame.

Paolo and Brother Remy

Paolo, the court musician, serves as a playful but surprisingly resourceful figure. His charm masks a deep loyalty, and his role in Elea’s escape marks him as a hero in his own right.

He understands court dynamics and uses wit to navigate its dangers. Brother Remy, by contrast, is a symbol of quiet resistance within the Church.

His support in Elea’s darkest hour—joining her rescuers despite the risk—cements him as a figure of moral clarity. Together, they show how unlikely alliances can challenge and dismantle oppressive power structures.

Themes

Gender and Medical Authority

The narrative of Eleanore of Avignon sharply critiques the limitations placed on women in the medieval world, particularly within the field of medicine. Eleanore’s vast knowledge—gleaned from her mother Bietriz and honed through observation and intuition—is persistently undermined by her lack of formal education and societal status.

Despite repeatedly saving lives and succeeding where male physicians fail, she is viewed with suspicion and hostility, especially by those invested in maintaining patriarchal structures. The novel juxtaposes institutional medicine, symbolized by Guigo and the papal court, with folk healing, embodied by Eleanore.

Through her journey, the story illustrates how misogyny not only sidelines women but also stifles potentially life-saving knowledge. The societal refusal to legitimize female healers leads directly to persecution, as seen in Eleanore’s arrest and trial for witchcraft—an echo of the tragic fate of her mother.

The use of her anatomical drawings and herbal records as damning evidence reflects a systemic fear of educated women. Even her eventual recognition and minor professional victories cannot entirely offset the personal cost of working in a male-dominated world.

The theme underscores the paradox of a society that demands healing yet punishes the healers when they don’t conform to sanctioned roles.

Faith, Superstition, and the Church

Religion plays a dual role in Eleanore of Avignon, functioning as both a source of comfort and a weapon of persecution. Characters like Father Loup embody the Church’s darker tendencies—zealotry, misogyny, and the manipulation of doctrine to serve power.

His refusal to grant Bietriz her last rites and his public condemnation of Eleanore underscore the Church’s capacity for cruelty, especially when confronted with knowledge or behavior that challenges orthodoxy. Meanwhile, the papal court’s embrace of medical experimentation, especially in times of crisis, reveals the Church’s contradictions.

It seeks healing and practical wisdom but is quick to brand that same wisdom as heresy when convenient. The arrival of the flagellants, the Queen’s politically controversial absolution, and the frequent invocation of divine punishment all suggest a populace trapped between spiritual need and institutional oppression.

Eleanore, though not irreligious, must navigate this treacherous landscape, where her every action is scrutinized through a lens of suspicion and superstition. Her ability to maintain moral clarity and a sense of spiritual purpose without succumbing to dogma speaks to a personal faith rooted in empathy rather than fear.

Love, Loyalty, and Sisterhood

Eleanore’s emotional arc is defined by her intense relationships, particularly with her twin sister Margot. Their bond is strained by grief, misunderstanding, and diverging values, yet it remains central to Eleanore’s identity.

Margot represents a life Eleanore might have had—conventional, protected, rooted in marriage and societal norms. That Margot ultimately sacrifices herself to save Eleanore is not only a tragic twist but a profound testament to the strength of their bond.

Her final message—“You are myself”—reverberates with meaning, affirming that sisterhood transcends betrayal, fear, and even death. Eleanore’s love for David, though tender and passionate, is fraught with peril due to his Jewish identity.

Their connection, marked by shared idealism and mutual respect, challenges the era’s strict social boundaries. Yet Eleanore’s repeated refusal to abandon her obligations for romantic fulfillment reflects a broader theme: love must coexist with duty.

She consistently chooses service over sanctuary, a choice that defines her not only as a healer but as a hero.

Plague, Suffering, and the Ethics of Care

The looming presence of the Black Death is not just a historical backdrop in Eleanore of Avignon, but a philosophical and ethical crucible. Eleanore’s decision to continue her work amidst growing danger is a moral stand against despair and abandonment.

Her participation in experimental procedures, her care for the disfigured and dying, and her capacity for compassion under duress underscore an ethical framework rooted in sacrifice and hope. The juxtaposition of her tender treatment of the injured dog Baldoin with her clinical, precise medical work highlights a holistic view of care—one that encompasses emotional and physical well-being.

The plague amplifies existing inequalities, magnifying the suffering of the poor, the Jewish, and the marginalized. Eleanore’s refusal to look away, even when offered escape, signals a belief that care must be radically inclusive.

Her efforts—often unrecognized or punished—are acts of resistance against a society paralyzed by fear and consumed by scapegoating.

Legacy, Memory, and Female Lineage

At its heart, Eleanore of Avignon is a story about a woman trying to reclaim and preserve the legacy of another. Bietriz’s presence permeates the novel—not just as a memory but as a guiding force.

Her teachings, methods, and philosophy live on through Eleanore, who struggles to protect them from erasure. The theme of legacy is embodied in every choice Eleanore makes: her insistence on using hawthorn, her drive to prove her intuition against academic skepticism, and her defense of knowledge even under threat of death.

The patriarchal systems around her attempt to erase Bietriz’s name, distort her work, and vilify her daughter, but Eleanore’s survival and eventual success ensure that memory persists. Even the Queen’s acknowledgment and eventual rewards serve as institutional recognition of a female lineage that was once scorned.

The final voyage, with David at her side and her sister’s voice in her heart, frames the continuation of that legacy—not as a quiet preservation but as a forward-looking reclamation. It is a call to future generations of women to remember, to resist, and to rebuild.