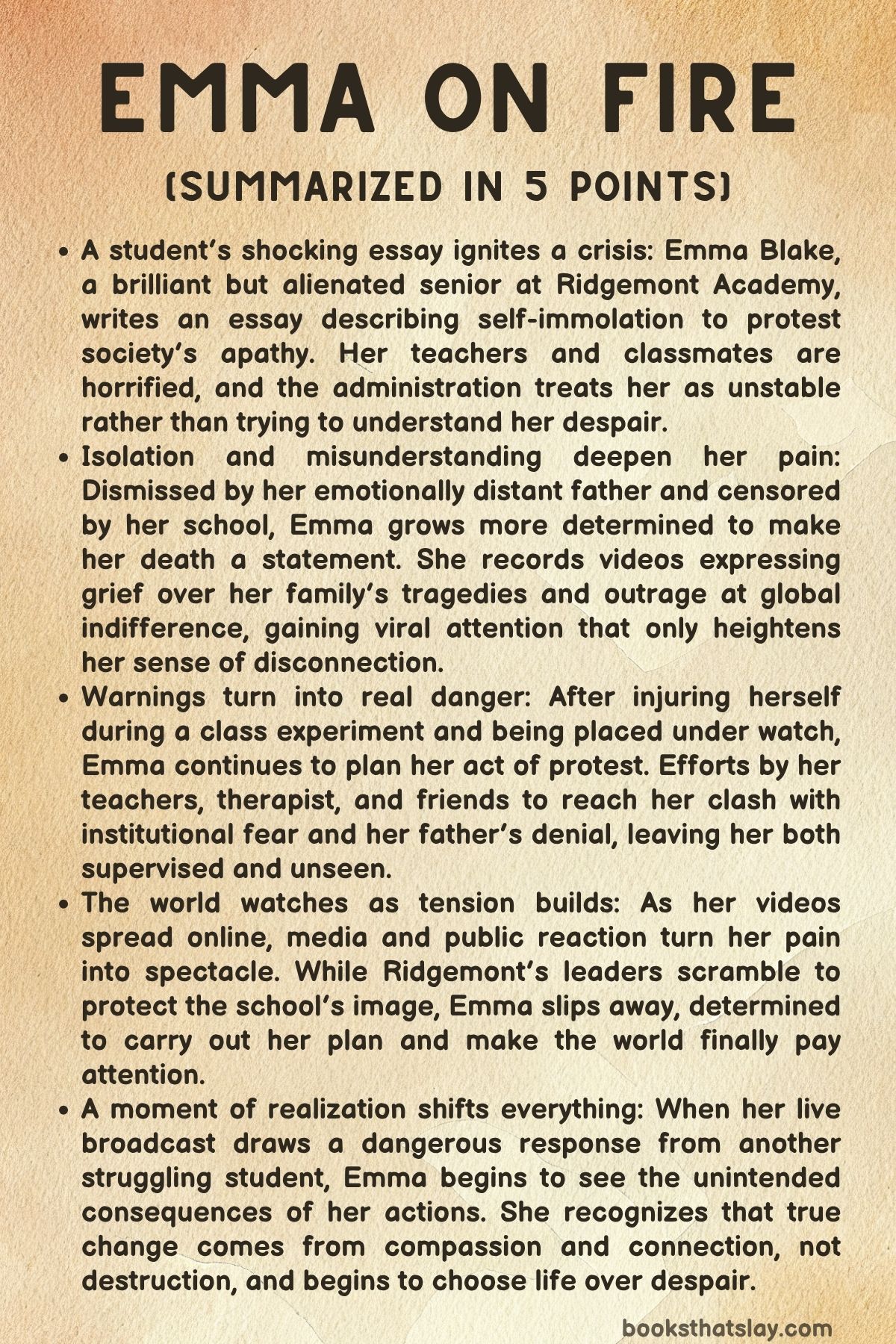

Emma on Fire Summary, Characters and Themes

Emma on Fire by James Patterson is a psychological and social drama that explores the dangerous intersection of grief, privilege, and the desire for meaning. Set in the elite world of Ridgemont Academy, it follows Emma Caroline Blake, a brilliant but tormented teenager determined to make a statement that forces people to wake up from their complacency

After losing her mother and sister, Emma’s pain turns into a plan for self-destruction disguised as protest. Patterson examines how institutions, family, and media respond to a young woman on the edge—raising uncomfortable questions about empathy, attention, and what it really means to be heard.

Summary

Seventeen-year-old Emma Blake is a senior at Ridgemont Academy in New Hampshire, an exclusive prep school filled with privilege and pressure. Once one of its brightest students, Emma has grown disillusioned after losing her mother to illness and her sister Claire to suicide.

Alienated by the school’s shallow environment and her father’s emotional neglect, she becomes consumed by anger at humanity’s indifference—especially to the planet’s collapse. This fury takes shape when she writes a shocking essay about burning herself alive as a form of protest against complacency.

When Emma reads her essay aloud in AP English, the explicit imagery horrifies her teacher, Mr. Montgomery, who stops her mid-sentence and sends her to Headmaster Peregrine Hastings.

Emma defends her essay as legitimate art, arguing that true writing should wake people up. Hastings and Montgomery are disturbed by her insistence that she intends to carry out the act.

They try to frame her behavior as unresolved grief over her mother’s death, but Emma rejects their euphemisms and hypocrisy. When they ask her to rewrite the essay on a more “acceptable” topic, she refuses, saying polite essays don’t change the world.

She leaves the office frustrated, convinced that Ridgemont cares more about appearances than truth.

Hastings worries privately that Emma’s talk may not be a bluff. He calls her father, Byron Blake, a cold and distant attorney.

Byron brushes off concerns, describing Emma as dramatic but strong. He refuses to visit her, insisting she’s “too tough to break.

” Hastings, powerless and uneasy, senses that Emma is completely alone.

That night, unable to sleep, Emma records a video titled “Fire Video #1,” announcing her intention to set herself on fire to protest humanity’s apathy toward global crises. She uploads it to YouTube, and the video begins to spread.

The next morning, Emma, exhausted, stares blankly through her classes. In chemistry, she holds her arm over a Bunsen burner, enduring the pain until her partner knocks her away, sparking a small fire.

Her injury leads to another meeting with Hastings and Montgomery, where she claims it was just an “experiment. ” Her father’s only comment is that pain is “weakness leaving the body.” Gossip soon spreads across campus, branding her a lunatic. Even so, some students—like Rhaina, a quiet classmate—see her distress and try to reach out, though Emma dismisses them.

The school sends her to counseling with Lori Bly, the academy therapist. Emma mocks the process but admits to both physical and emotional pain.

Lori senses her despair but cannot break through her sarcasm. That evening, Emma shares with her friends Jade and Celia an unpublished letter she wrote for the school paper, blaming Ridgemont’s perfection culture for her sister’s death.

When she borrows Celia’s car, she secretly plans to use it to buy gasoline.

Later, she records “Fire Video #2,” a detailed manifesto listing the world’s crises and setting the date of her self-immolation. By morning, the video has gone viral, making her an online sensation.

Reporters arrive, and the administration panics. Headmaster Hastings and the therapist decide to isolate her in a secure guest room for “rest,” removing her phone and computer.

Emma calls it a “gilded cage” but complies outwardly while plotting her escape. She’s visited by her old teacher, Ms.

Reddington, who shares memories of Emma’s mother and urges her to live. Emma listens politely but remains committed to her plan.

Her ex-boyfriend, Thomas Takeda, later visits. For a moment, Emma feels the pull of love and normalcy, but the heaviness of grief wins out.

When he confesses that he still loves her, she pushes him away. The next day, her father arrives, more irritated than concerned.

Emma confronts him about Claire’s death, but he retreats into cold rationality. The gulf between them widens, reinforcing her conviction that no one understands.

Meanwhile, the Boston Globe publishes an article about her videos, framing her as unstable rather than prophetic. Hastings, under pressure from the board, decides to hospitalize her.

But Emma leaves campus before they can act, walking miles to buy gasoline and hiding at a motel under her late sister’s ID. As her story floods social media, she’s both enraged and hollow—her message has turned into memes and mockery.

After a painful call with her father, in which both confront their guilt over Claire’s death, Emma cuts him off and prepares for her final act.

At dawn, she returns to campus, evading security. A student spots her drenched in gasoline, holding a lighter.

She runs to the journalism room, barricades the door, and starts a live stream titled “Emma On Fire. ” Thousands tune in as she speaks about grief, environmental collapse, and society’s moral decay.

She insists her death will be a wake-up call, unlike her sister’s. Meanwhile, Hastings and Thomas rush to find her while police surround the building.

As Emma speaks, a message appears from Rhaina: “You can be the first. I’ll go next.” The words stun Emma. She realizes her actions are inspiring others to die, not to live.

The chat fills with despairing messages, and Emma sees how her protest could unleash a wave of suicides. Understanding the weight of her influence, she changes course.

She tells her viewers she no longer wants to die, that her message was never meant to cause more pain. She urges everyone to look after one another, to choose hope over despair, and to keep fighting for the planet and for themselves.

“We may feel hopeless,” she says, “but we aren’t helpless.

She ends the stream and opens the barricaded door. Hastings and Thomas rush in.

Thomas hugs her tightly, while Hastings takes the lighter from the floor. Emma pleads for help for Rhaina and her roommate Olivia, realizing now that small acts of care matter most.

Hastings promises to act, and Emma breaks down, surrounded by people who won’t let her face the darkness alone.

The next morning, after a night in the hospital with her father at her side, Emma walks through campus under the blooming magnolias. For the first time, she feels life’s quiet beauty instead of its futility.

When reporter Rachel Daley asks for a comment, Emma refuses to let her story become another tragedy. “The story,” she says, “is that I’m still here.” Later, she writes a letter to her late sister Claire, recalling a childhood memory and promising to keep living for both of them. The book closes on Emma’s decision to begin again—scarred, but alive, and finally choosing hope over fire.

Characters

Emma Caroline Blake

Emma Blake is the complex and emotionally volatile protagonist of Emma on Fire. A brilliant and introspective senior at Ridgemont Academy, Emma’s character embodies the deep conflict between youthful idealism and personal despair.

Her intelligence is both her gift and her curse—she perceives the hypocrisy of her privileged world with painful clarity and refuses to accept the shallow complacency around her. Haunted by the deaths of her mother and sister, Emma channels her grief into a desperate search for meaning.

Her essay on self-immolation serves as both a cry for help and a statement of rebellion, revealing her yearning to shake people from moral apathy.

Emma’s psychological unraveling is portrayed through her isolation and obsessive focus on global suffering. Her protest against climate change and societal numbness becomes a projection of her own internal agony.

The school’s failure to understand her, along with her father’s cold detachment, drives her to the edge. Yet, beneath her defiance lies a longing for connection and recognition of pain.

When she finally realizes that her death could inspire others to self-destruction rather than awareness, Emma’s evolution becomes clear. She chooses compassion over martyrdom, rediscovering the will to live and understanding that true change comes from empathy, not self-sacrifice.

Peregrine Hastings

Headmaster Peregrine Hastings is portrayed as a man torn between institutional duty and genuine concern for Emma. Initially, he represents the embodiment of Ridgemont’s rigid decorum—a leader obsessed with reputation, procedures, and the appearance of stability.

However, as Emma’s crisis escalates, Hastings transforms from a bureaucratic figure into a conflicted human being who recognizes the depth of her pain. His character illustrates the limits of authority when faced with moral and emotional chaos.

Hastings’ internal conflict—between protecting the school’s image and protecting Emma’s life—mirrors the novel’s central tension between public perception and private suffering. Despite his administrative caution, he grows increasingly compassionate, coordinating efforts to find and save Emma during her livestream.

In the end, his decisive actions and willingness to confront Emma’s father show his moral growth. Hastings becomes a quiet symbol of responsibility and care within a system otherwise paralyzed by formality and fear.

Byron Blake

Byron Blake, Emma’s father, represents emotional sterility and the damaging legacy of denial. A high-powered attorney, Byron is consumed by ambition and control, using work as armor against grief.

His interactions with Emma are marked by emotional distance and dismissiveness, revealing his inability—or refusal—to engage with her suffering. His repeated phrase, “Pain is weakness leaving the body,” encapsulates his worldview: strength through suppression, not understanding.

Byron’s indifference toward both of his daughters’ psychological struggles exposes the toxic masculinity underlying his character. He mistakes Emma’s brilliance and stubbornness for resilience, failing to see her unraveling.

However, his late arrival at the hospital and quiet presence after her rescue suggest the faintest stirrings of paternal remorse. Byron is not a villain but a tragic embodiment of a generation that equates emotional avoidance with strength, leaving destruction in its wake.

Lori Bly

Lori Bly, the school therapist, stands as one of the few adults who genuinely attempt to reach Emma. Her patient, empathetic demeanor contrasts with the cold pragmatism of other faculty members.

Lori’s own grief over her brother’s suicide allows her to understand Emma’s anguish, but her professional boundaries limit her effectiveness. Despite recognizing the danger, she must operate within institutional constraints that prioritize documentation and containment over emotional healing.

Lori’s role highlights the novel’s critique of systems that medicalize pain rather than address its causes. Through her sessions with Emma, the reader glimpses the possibility of understanding and recovery, though this hope is constantly thwarted by bureaucracy.

Lori’s compassion humanizes the story’s adult figures and underscores the tragic gap between empathy and institutional power.

Thomas Takeda

Thomas, Emma’s ex-boyfriend, represents the voice of reason and love amidst the chaos. His reappearance in Emma’s darkest moment serves as a mirror to her humanity.

Thomas’s calm, grounded presence contrasts sharply with Emma’s spiraling despair. He embodies the theme of genuine connection—the antidote to isolation.

His persistence in trying to reach Emma emotionally, even after their breakup, reveals his enduring affection and moral courage.

Thomas’s confession that he still loves Emma rekindles a fleeting spark of hope within her. His intervention helps her see herself not as a symbol but as a person worthy of care.

Thomas symbolizes the power of empathy to cut through despair; his emotional authenticity reminds Emma—and the reader—that love and understanding are the truest forms of resistance to a broken world.

Rhaina

Rhaina’s character, though secondary, becomes pivotal in Emma’s transformation. A quiet, artistic student, she initially appears as a concerned classmate but later emerges as the unexpected reflection of Emma’s despair.

When she messages Emma during the livestream—“You can be the first. I’ll go next.

”—she forces Emma to confront the devastating consequences of her intended protest. Rhaina personifies the unseen suffering of others, revealing that Emma’s radical act could perpetuate harm rather than healing.

Through Rhaina, the story explores the contagion of hopelessness in the digital age, where one person’s pain can quickly inspire others to self-destruction. Her presence transforms Emma’s perception of her mission—from self-immolation as protest to life as activism.

Rhaina becomes the quiet savior who, through her own despair, saves Emma from hers.

Rachel Daley

Rachel Daley, the journalist, embodies the ethical ambiguity of modern media. Initially portrayed as opportunistic and exploitative, Rachel views Emma’s crisis as a sensational story that could captivate the public.

Her intrusion into Ridgemont reflects society’s voyeuristic fascination with tragedy. However, Rachel’s later attempt to retract her article and connect with Emma on a more human level adds nuance to her character.

Rachel symbolizes the broader theme of truth versus exploitation. While she seeks to control Emma’s narrative, she ultimately becomes a catalyst for Emma’s final assertion of agency.

When Emma tells Rachel that the real story is not her death but her choice to live, Rachel’s role completes its transformation—from manipulator to witness. Through Rachel, Emma on Fire critiques the media’s power to distort human suffering while acknowledging its potential to spread awareness.

Olivia

Olivia, Emma’s roommate, represents the self-absorbed superficiality that Emma despises at Ridgemont. Engrossed in her online persona and OnlyFans content, Olivia symbolizes a generation obsessed with visibility but devoid of depth.

Her detachment from Emma’s turmoil underscores the alienation that fuels the protagonist’s despair. Yet, Olivia is not malicious; she is simply emblematic of a world too distracted to notice real pain.

By the novel’s end, when Emma asks Hastings to look after Olivia, the gesture signifies her newfound empathy. Emma no longer condemns others for their flaws but sees them as part of a shared human struggle.

Through Olivia, the story closes the circle—from judgment to understanding, from isolation to compassion.

Themes

Alienation and the Search for Meaning

In Emma on Fire, alienation forms the emotional center of Emma Blake’s crisis. Isolated in the elitist corridors of Ridgemont Academy, she confronts an environment obsessed with image, grades, and appearances, yet devoid of empathy or authenticity.

Her essay on self-immolation becomes both a cry against this spiritual emptiness and an act of rebellion against a society that rewards conformity. Emma’s estrangement deepens with every interaction—her teachers interpret her pain as disciplinary trouble, and her father reduces her anguish to “drama.

” Her alienation is not merely social but existential; she feels unanchored in a world where material comfort coexists with moral decay. This emotional disconnection mirrors the modern crisis of purpose, where digital validation replaces human understanding.

Emma’s alienation pushes her toward the illusion of control through destruction—believing that setting herself on fire will finally make her visible. Yet, as the novel unfolds, this alienation becomes the very force she must transcend.

When Emma finally confronts the realization that others might die following her example, she recognizes the futility of isolation. Her decision to live redefines meaning as an act of connection rather than spectacle.

Through her awakening, James Patterson portrays alienation not as an end but as a crucible—an agonizing phase that precedes empathy and self-discovery.

Grief and Psychological Disintegration

The novel presents grief as both a personal and generational affliction. Emma’s descent begins not with her essay but with the compounded loss of her mother to cancer and her sister Claire to suicide.

Ridgemont’s sterile response to these tragedies—labeling them “life challenges”—exposes the institutional discomfort with grief, a reflection of society’s refusal to engage with pain. Emma internalizes this avoidance, carrying unspoken guilt and anger that distort her perception of the world.

Her self-destructive impulses are less about death itself and more about transforming her unbearable sorrow into something meaningful. Grief becomes a silent contagion: her sister’s suicide opens a wound that the family never closes, and her father’s emotional absence reinforces her conviction that suffering is invisible unless dramatized.

Patterson’s portrayal of Emma’s mental unraveling is relentless yet humane, tracing how grief erodes boundaries between moral protest and self-destruction. The novel’s climax—Emma’s livestream confrontation with Rhaina—exposes grief’s ripple effect, where one person’s pain can endanger others.

In choosing life, Emma does not erase her grief but learns to coexist with it, transforming it from a source of annihilation into a foundation for empathy. The narrative suggests that healing does not lie in forgetting loss but in reengaging with life despite its persistence.

Hypocrisy of Institutions and Moral Cowardice

Ridgemont Academy functions as a microcosm of societal hypocrisy—a place where prestige masks decay. The school’s leaders, especially Headmaster Hastings, claim to care for students but act primarily to protect reputation and donor relations.

Their responses to Emma’s crisis—containment, censorship, and legal consultation—expose the bureaucratic instinct to manage optics rather than confront truth. The institution’s moral cowardice extends beyond the school walls; it mirrors the larger world that Emma condemns in her videos.

The adults around her interpret sincerity as instability and rebellion as pathology. This hypocrisy feeds Emma’s disillusionment, convincing her that authenticity has no space in systems built on denial.

Even the media, represented by reporter Rachel Daley, exploits Emma’s suffering for sensational headlines, proving that the hunger for narrative eclipses compassion. Patterson uses these interactions to critique how institutions sanitize tragedy, converting it into administrative data or public relations strategy.

Emma’s final confrontation with these forces—her insistence that the “real story” is her choice to live—becomes an indictment of moral evasion. The hypocrisy theme thus evolves into a test of integrity: whether individuals and systems can value truth over image, empathy over control.

In the end, Emma’s survival stands as both a rebuke and a fragile hope against institutional indifference.

Activism, Despair, and the Ethics of Protest

Emma’s planned self-immolation raises difficult questions about activism and morality. Her conviction that personal sacrifice can awaken a numb world draws from historical acts of protest, yet Patterson complicates this idealism by exposing its psychological and ethical costs.

Emma’s plan is born not from pure courage but from despair—an attempt to make meaning in a world that ignores suffering. Her reasoning reflects a generational exhaustion with performative activism: petitions, hashtags, and “Earth Day” slogans that fail to address systemic collapse.

Yet the novel warns that transforming activism into martyrdom risks replicating the violence one seeks to oppose. When Rhaina declares she will follow Emma into death, the moral paradox crystallizes: an act meant to awaken conscience instead spreads destruction.

Emma’s realization that true change begins with compassion, not spectacle, becomes the novel’s moral hinge. Her closing plea—“Take care of each other”—reframes activism as relational rather than sacrificial.

Patterson suggests that despair and hope coexist within the same impulse to resist. By rejecting death and choosing to live responsibly, Emma redefines protest as endurance, courage, and care.

The narrative ultimately affirms that the most radical form of rebellion in a dying world is not self-destruction but the persistent will to nurture life.