Eve by Cat Bohannon Summary and Analysis

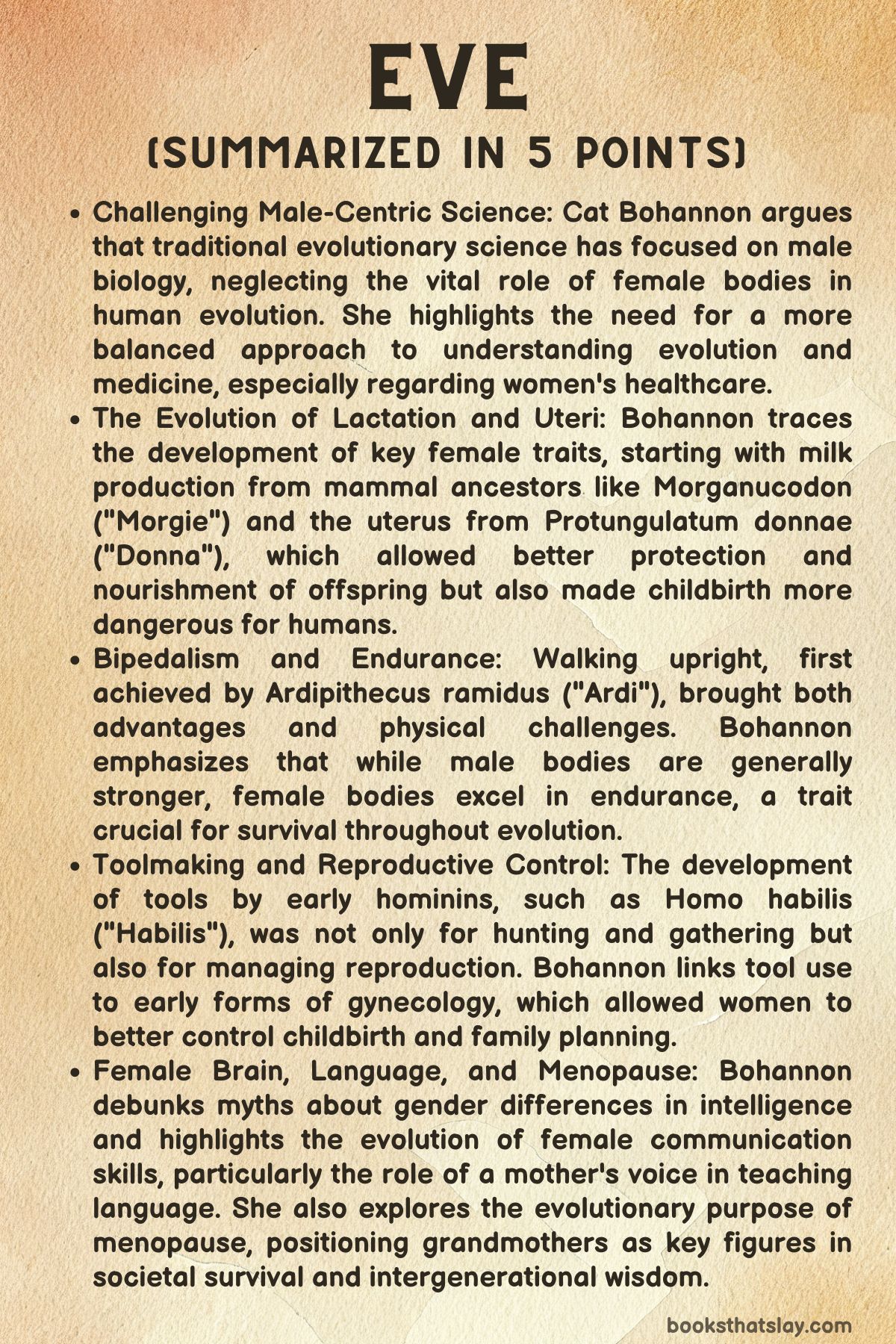

“Eve: How the Female Body Drove 200 Million Years of Human Evolution” by Cat Bohannon is a groundbreaking work that explores the often-overlooked role of female bodies in shaping human evolution. Bohannon, a scientist, challenges the male-centric bias in evolutionary science, emphasizing how traits like lactation, pregnancy, bipedalism, and menopause have been critical to the development of humans as a species.

By tracing the evolutionary journey through various “Eves” – key female ancestors – Bohannon demonstrates how female biology has shaped not only human survival but also societal structures, and offers a fresh perspective on women’s vital contributions to our shared history.

Summary

In Eve, Cat Bohannon presents a compelling argument that evolutionary science and medicine have traditionally prioritized the male body, leading to a knowledge gap in understanding female biology.

Her response is a thorough exploration of the female body’s influence on human evolution, tracing it through critical evolutionary stages by focusing on a series of female ancestors she calls “Eves.”

The journey begins with Morganucodon, whom Bohannon refers to as “Morgie,” a mammal from whom we inherited lactation. Bohannon discusses how milk evolved as a critical survival tool, allowing mammals to nourish and protect their young from external dangers.

Breast milk, she explains, not only provides sustenance but also boosts the immune system and helps babies adapt to their environment. The ability to produce milk, she suggests, paved the way for larger communities and, eventually, urbanization.

Wet nursing practices further enabled human populations to grow, as mothers could share the responsibility of feeding.

The narrative then shifts to “Donna,” an early mammal named Protungulatum donnae, from whom the uterus evolved. The development of internal gestation was revolutionary, allowing better protection for offspring from external threats.

Yet, this also made childbirth far more dangerous for humans as their brains and bodies evolved. Bohannon links this back to menstruation, which emerged as a biological adaptation to handle the complexities of pregnancy. Following the catastrophic Chicxulub event, the pressures on mammalian ancestors led to the emergence of primates like Purgatorius, nicknamed “Purgi,” the Eve of perception.

This early primate adapted to life in trees, developing sharper senses necessary for survival, which, as Bohannon highlights, have persisted in modern women, who statistically have superior senses of smell, sight, and hearing compared to men.

Bohannon then introduces Ardipithecus ramidus, or “Ardi,” the Eve of bipedalism, who was among the first hominins to walk upright. However, walking on two legs came at a physical cost, particularly for women, who are more prone to foot and knee issues.

This section includes a reflection on the endurance of female bodies, arguing that while men may have greater strength, women excel in endurance—a trait that has been vital for survival throughout human evolution.

As toolmaking becomes a significant evolutionary marker, the book introduces Homo habilis, or “Habilis,” the creator of early tools and possibly the first to practice gynecology, enabling women to manage reproduction more effectively.

Bohannon draws a striking parallel between Habilis’s tool use and Stanley Kubrick’s famous film 2001: A Space Odyssey, implying that the mastery of tools was pivotal for human advancement.

In the final stretch, Bohannon delves into the evolution of the human brain, language, and communication.

She dismantles gendered stereotypes about intellectual ability, suggesting that brain differences between men and women are often exaggerated or misinterpreted due to social factors.

She also emphasizes that female voices, although softer and less powerful than male voices, have evolved to communicate more precisely, particularly between mothers and their babies.

Bohannon concludes with a thought-provoking discussion on menopause, love, and sexuality, examining the evolutionary role of grandmothers in human society and the shifting dynamics between the sexes.

Ultimately, she challenges patriarchy and calls for a more equitable society where the contributions of women are fully recognized and valued.

Analysis

The Female Body as a Central Driver of Evolutionary Development

Cat Bohannon’s work places the female body at the heart of human evolutionary progress, challenging the traditional male-centric narratives of science.

Her exploration begins with the premise that evolutionary science has often treated the male body as the biological default, an oversight that not only skews our understanding of human evolution but also has far-reaching implications for healthcare and society.

By reconstructing an evolutionary timeline that prioritizes the female body, Bohannon asserts that many of the defining characteristics of Homo sapiens—including lactation, childbirth, sensory perception, and brain development—were driven by the unique biological needs and adaptations of female ancestors.

She contends that the ability to lactate, as seen in early mammalian ancestors like Morganucodon, was not a trivial byproduct of evolution but a fundamental force that shaped the survival and social structures of early humans.

The development of breasts and milk, for example, did more than just feed offspring; it helped create early social systems, teaching young mammals about their environment and laying the groundwork for human urbanization through the advent of wet nurses.

Bohannon’s reframing of evolution forces us to reconsider the essential role of female biology in the survival and flourishing of the human species.

Female Endurance, Bipedalism, and the Evolutionary Costs of Strength

Bohannon’s narrative highlights a critical theme often overlooked in evolutionary discourse: the unique strength of female bodies, particularly their capacity for endurance over raw physical power. Through the example of Ardipithecus ramidus, she demonstrates that while bipedalism was a transformative evolutionary step, it also came with significant physical costs—especially for women.

The shift to walking on two legs introduced strain on the legs, feet, and hips, which, Bohannon argues, disproportionately affects female bodies due to their different biomechanical structure. Yet, she positions this not as a disadvantage, but as a key to understanding female strength.

The capacity for endurance, both physical and emotional, becomes a recurring motif in the evolutionary tale she weaves. Bohannon uses the story of Captain Griest’s training as an Army Ranger to illustrate that although male bodies are often physically stronger, female bodies have evolved to withstand immense endurance challenges—whether through childbirth or survival under extreme conditions.

This endurance is evolutionary in nature, a trait passed down from ancestors who had to persevere in dangerous and demanding environments.

The Intersection of Toolmaking, Reproductive Control, and Female Agency

Bohannon delves into the transformative relationship between toolmaking and reproductive control, tracing it back to early hominins like Homo habilis. She argues that toolmaking was not just about survival in terms of hunting or gathering, but also about gynecology—an essential, often overlooked form of technological advancement.

Female hominins learned to manipulate their reproductive systems, controlling fertility and childbirth, thus granting themselves greater agency in deciding when and how to bear offspring.

This represents a fundamental shift in how we understand toolmaking, moving away from the stereotypically male-dominated narrative of primitive weapons and toward a recognition of women’s influence on technological progress.

By managing their reproduction, female hominins contributed to healthier offspring and longer lifespans, which in turn catalyzed the social and cognitive evolution that would follow. Bohannon’s comparison of this evolutionary leap to the iconic scene in 2001: A Space Odyssey underscores the profundity of this moment—it was not just the use of tools, but the evolution of human agency and control over biology itself.

Female Sensory Perception and Cognitive Evolution as Adaptive Strategies

Another central theme Bohannon addresses is the advanced sensory perception that evolved in female primates, particularly in relation to hearing, smell, and sight. Through the lens of Purgatorius, the first primate ancestor to develop these heightened senses, Bohannon connects the evolutionary significance of perception to survival in early environments.

She argues that female individuals, driven by the need to protect their offspring and gather food, developed keener sensory abilities, which gave them an evolutionary edge. These abilities, Bohannon suggests, are still present in modern women, who statistically outperform men in certain sensory-based tasks.

By emphasizing this aspect of evolutionary history, she challenges the modern gendered assumptions about cognitive and sensory abilities.

Her argument implies that the traditional narrative of male dominance in cognitive faculties is misguided, overlooking the evolutionary importance of female-perception abilities that played a crucial role in the survival and success of early humans.

Bohannon also examines how female primates’ enhanced perception facilitated communication, social bonding, and the early development of language—a capacity that would later shape human culture and intellectual development.

Brain Development, Motherhood, and the Female Contribution to Language

The evolution of the human brain, according to Bohannon, is deeply entwined with motherhood and female linguistic contributions.

She takes a unique stance by arguing that the development of language, one of the most distinctive human traits, was likely driven by mothers communicating with their babies.

This maternal relationship, Bohannon suggests, was the first source of storytelling, a medium through which early humans made sense of their world and passed on crucial survival information. The nurturing brain, shaped by the pressures of motherhood, was a significant factor in the cognitive leap that allowed Homo sapiens to dominate the planet.

Bohannon confronts the conventional wisdom that men are biologically more intelligent or emotionally stable, instead arguing that social pressures, environmental factors, and entrenched gender roles skew these perceptions.

The evolutionary significance of motherhood in shaping the brain reveals that maternal care was more than a nurturing act—it was an essential force driving human intelligence, creativity, and the ability to communicate complex ideas.

Thus, female brains, shaped by the pressures of care and communication, contributed fundamentally to the evolution of speech, storytelling, and culture.

Menopause, Post-Reproductive Life, and the Evolution of Wisdom

Menopause, often seen as a biological disadvantage, is reinterpreted by Bohannon as a crucial evolutionary adaptation that granted older women the role of wisdom keepers within early human communities.

She posits that menopause evolved because female bodies, which are more likely to survive to old age, provided indispensable guidance and knowledge for their descendants.

Bohannon links this phenomenon to the “grandmother hypothesis,” which suggests that post-reproductive women played a pivotal role in increasing the survival rates of their grandchildren by offering care and imparting wisdom.

This knowledge, passed down across generations, likely included crucial information about childbirth, survival tactics, and environmental adaptation.

Bohannon’s narrative also explores the emotional complexity of menopause, framing it as a period in which women confront loss—particularly the loss of male partners due to shorter male lifespans—while simultaneously gaining independence and social authority.

This recontextualization of menopause challenges contemporary views that see it as a biological endpoint, presenting it instead as a key stage in the life cycle of human evolution.

The Evolutionary Role of Patriarchy, Love, and the Subversion of Gender Power Dynamics

Finally, Bohannon offers a thought-provoking analysis of how patriarchy evolved as a survival mechanism but has since become maladaptive and harmful.

She theorizes that early human societies were likely matriarchal, with female individuals forming cooperative groups for the protection and care of offspring.

However, as societies became more complex, female hominins formed monogamous relationships with males, which eventually led to the establishment of patriarchal structures.

These patriarchies, while perhaps beneficial in early human history, now inhibit societal progress by stifling female autonomy and hindering the potential of future generations.

Bohannon warns that modern gender inequalities, rooted in these ancient structures, have harmful consequences for women’s health, children’s development, and societal prosperity.

Her call for a reimagining of power dynamics suggests that humanity must confront the legacy of patriarchal systems in order to fully realize the potential of both genders.

By framing patriarchy as an evolutionary byproduct rather than a natural order, Bohannon invites readers to consider how gender roles have evolved and how they might be reshaped to promote equality and progress in a modern context.