Family of Spies Summary, Characters and Themes

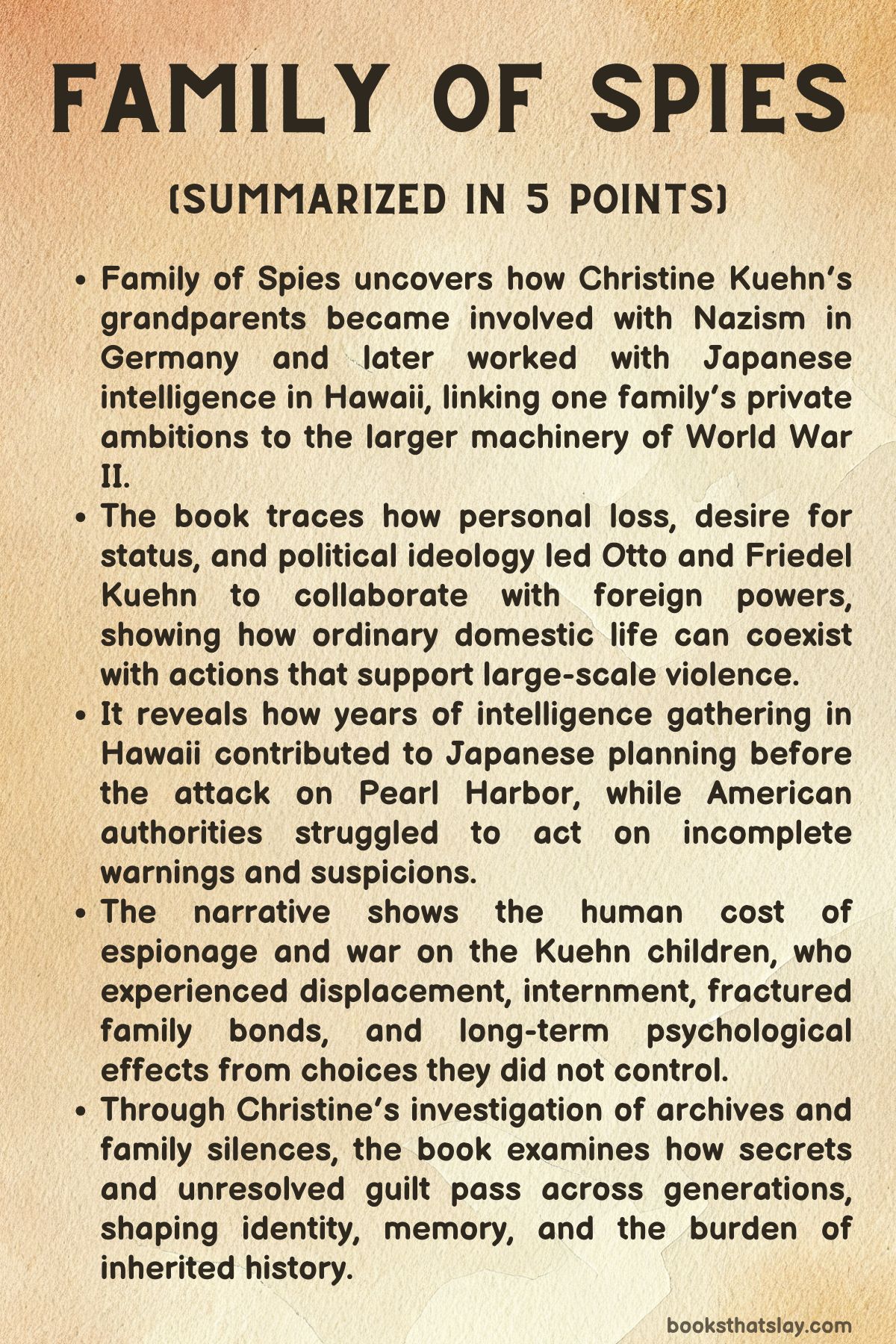

Family of Spies by Christine Kuehn is a work of narrative nonfiction that investigates a buried family history tied to the rise of Nazism and the attack on Pearl Harbor.

Writing as both historian and descendant, Kuehn reconstructs how her grandparents became involved in German and Japanese intelligence networks before World War II, and how those choices reshaped the lives of their children and grandchildren. The book moves between personal memory, archival research, and declassified records to examine how ambition, ideology, and fear led one family into collaboration with violent regimes. At its core, the book is about inherited silence, moral responsibility, and the long afterlife of secrets.

Summary

Christine Kuehn grows up in Florida hearing her father, Eberhard, tell entertaining stories about his youth and military service. He presents himself as a man who left Germany behind and built a quiet American life. What he does not talk about are his parents, his childhood in Nazi Germany, or the circumstances that brought him to Hawaii before the war. When Christine is young, her half brother appears unexpectedly at their home, and her father urgently tells him not to speak about the family. The warning makes little sense at the time, but it signals that something in the family past is being carefully hidden.

Years later, Christine learns that her father had once shared painful details about his upbringing with his first wife. In moments of anger, she threw those details back at him, accusing him of being connected to Nazism. The experience teaches him that speaking about the past brings only harm, and he decides to protect his younger daughter by keeping silent. Christine grows up sensing that there is more to her family story, but she lacks the facts to understand what that might be.

In the 1990s, Christine receives a letter from a screenwriter researching Pearl Harbor. He tells her that historical records identify her grandfather, Otto Kuehn, as a German agent who worked with Japanese intelligence in Hawaii before the attack. Some accounts even suggest that members of the family helped guide Japanese bombers. Alarmed, Christine begins checking history books and archival sources. She finds her grandfather’s name repeated in serious studies of wartime espionage. The realization that her own family appears in these accounts forces her to confront the possibility that the people she thought she knew were involved in catastrophic events.

When Christine confronts her father, he first denies the claims. Over time, he admits that he had tried to bury the truth. He begins to describe his childhood in Germany and Hawaii, and what it was like to grow up inside a family that lived one life in public and another in secret.

Christine decides to investigate the full history of her grandparents, determined to understand how their choices connected her family to the attack on Pearl Harbor.

Otto Kuehn is born into wealth in Germany in the late nineteenth century. As a young man, he serves in the German navy during World War I and survives the sinking of his ship. He spends years as a prisoner of war. When he returns home, he finds his family fortune gone and much of his family dead. The loss of status and security leaves him bitter and restless.

He moves from one business venture to another, rarely succeeding. He marries Friedel, a woman with children from previous relationships, and adopts them as his own. For a time, the family regains prosperity through a coffee-import business in Berlin.

The economic collapse of the late 1920s and the political turmoil of the Weimar years leave Otto receptive to radical promises. He joins the Nazi Party early, drawn by its claims of national renewal and personal advancement. Friedel and the children follow him into the movement.

Their household becomes part of the new political order, and Otto works within Nazi intelligence circles. He navigates internal rivalries and violent purges, learning how quickly favor can turn into danger. The family benefits from the regime’s patronage while also living under constant risk.

One of the most complicated figures in the family is Ruth, Friedel’s daughter, who becomes deeply involved in Nazi youth organizations. She attracts the attention of powerful men, including Joseph Goebbels. At the same time, her background is precarious because her biological father was Jewish, a fact that places her at risk under racial laws.

The family’s position inside the regime is therefore unstable, dependent on secrecy and connections.

As political tensions rise in Europe, Otto’s work brings him into contact with Japanese intelligence. Through these connections, he secures an arrangement to operate in Hawaii, where Japan has a strong interest in U.S. military activity.

Otto and Friedel leave Germany under the cover of business travel and begin preparing to act as agents abroad. Their children are brought out of Germany soon after, escaping an environment that is becoming increasingly violent and dangerous.

In Hawaii, the family presents itself as a group of cultured Europeans adjusting to island life. Otto cultivates friendships with U.S. naval officers, hosting parties and positioning himself as a helpful local businessman.

Friedel and Ruth open a beauty shop and move easily within social circles connected to the military. Behind this social life, they gather information about ship movements, airfields, and base routines. The money that supports their lifestyle comes from Japanese sources, transferred through intermediaries and concealed channels. Over time, the scale of these payments grows, allowing the family to live far beyond what their declared businesses could support.

American authorities grow suspicious of the family’s finances and associations. The FBI monitors their mail, tracks their movements, and attempts to determine whether they are passing information to foreign powers.

The evidence is suggestive but incomplete, and legal limits make it difficult to act decisively. As global tensions escalate, the family remains under watch but continues to operate within a gray zone, benefiting from the openness of American society while quietly serving a hostile power.

At the same time, Japanese intelligence assigns trained officers to Honolulu under diplomatic cover. These agents conduct their own surveillance of Pearl Harbor, observing ship patterns and base defenses from public vantage points and through social contacts.

The intelligence gathered in Hawaii flows back to planners in Japan who are preparing for a possible conflict with the United States. Despite warnings from informants and intercepted communications, U.S. officials underestimate the likelihood of a direct attack.

In the days before the attack, Japanese diplomatic staff in Honolulu begin destroying sensitive materials. Otto receives instructions to activate a signaling system that could be used to communicate ship movements.

Although there is debate about how effective this system would have been, the overall picture that emerges is one of long-term preparation, with information accumulated over years contributing to Japanese planning.

When the attack on Pearl Harbor begins, it devastates the U.S. Pacific Fleet and kills thousands. In the immediate aftermath, authorities move quickly against suspected enemy agents. Otto, Friedel, Ruth, and their sons are arrested. Searches uncover cash, documents, and materials linked to foreign intelligence.

Otto is interrogated for long periods and eventually confesses to working with Japanese intelligence. Friedel maintains her silence, and the children are left to confront the reality that their father’s actions may have helped enable a disaster.

Otto is tried before a secret military commission. The proceedings are closed to the public, shaped by anger and fear in the wake of the attack. He is found guilty and sentenced to death. The secrecy of the trial and the speed of the verdict raise questions even among those who believe he was guilty.

As the government reviews similar cases involving foreign agents, legal doubts emerge about whether a military tribunal had jurisdiction over acts committed before the formal declaration of war. Otto’s sentence is ultimately commuted to a long prison term.

The family’s suffering does not end with Otto’s imprisonment. Friedel and the children are sent to internment camps as enemy aliens. Their lives are marked by separation, hardship, and stigma. Eberhard, who has grown disillusioned with Nazism, chooses to build his future in the United States.

He becomes a citizen and later serves in the U.S. Army, fighting in brutal campaigns in the Pacific. His service places him in direct conflict with the regime that shaped his childhood and the alliances his parents once served.

Decades later, Christine uncovers trial transcripts and government files that reveal in stark detail what her father and his siblings endured. She reflects on how secrecy shaped her family, how trauma passed silently from one generation to the next, and how personal choices became entangled with vast historical forces.

By reconstructing this history, she confronts the moral weight of her family’s past and the lasting consequences of decisions made in pursuit of power, belonging, and survival.

Key People

Christine Kuehn

Christine Kuehn, the narrator of Family of Spies, stands at the center of the story as both participant and investigator. Her role is defined by the tension between personal loyalty to her family and her commitment to uncovering historical truth. Raised with fragmented stories and deliberate silences, she grows up sensing that her father’s past is guarded by fear and shame.

As an adult, she approaches her family history with the tools of a researcher, consulting archives, trial transcripts, and historical accounts. Her emotional journey is shaped by the painful realization that people she loves are linked to acts of betrayal and violence on a national scale. Christine’s character reflects the burden carried by later generations who inherit unresolved moral questions and must decide whether to protect comforting myths or confront disturbing realities.

Eberhard Kuehn

Eberhard Kuehn, Christine’s father, embodies the long shadow cast by childhood inside a politically compromised family. As a boy, he is uprooted from Germany and carried into an espionage network in Hawaii without agency or understanding. His adult life is shaped by a desire to distance himself from his parents’ ideology and actions, yet he remains trapped by secrecy.

The trauma of having his family’s history used against him during his first marriage teaches him that honesty can be dangerous, leading him to conceal the truth from his younger daughter. His later decision to become an American citizen and fight for the United States reflects a conscious rejection of Nazism and an attempt at moral repair. Still, the silence he maintains within his family reveals how deeply fear and shame persist, even when beliefs have changed.

Otto Kuehn

Otto Kuehn emerges as the most morally fraught figure in Family of Spies, driven by ambition, resentment over lost status, and a desire for power and recognition. His early experiences of war, imprisonment, and financial ruin leave him eager for systems that promise restoration of honor and prosperity.

Nazism offers him both ideological certainty and practical opportunity, drawing him into intelligence work and violent internal politics. His move into espionage in Hawaii reflects not only political allegiance but also personal opportunism, as he accepts large sums of money and constructs a lavish life built on deception.

Otto’s later confession and conviction reveal a man who understands the gravity of his actions yet continues to see himself as acting within a code of loyalty rather than as a criminal. His character illustrates how personal grievance and hunger for status can evolve into collaboration with destructive forces.

Friedel Kuehn

Friedel Kuehn is portrayed as fiercely loyal to her husband and deeply committed to the ideological world that promises her family protection and importance. Her willingness to follow Otto into Nazism and later into espionage reflects a blend of belief, dependence, and survival instinct.

She plays an active role in sustaining the family’s operations in Hawaii, participating in social networks that facilitate intelligence gathering while maintaining the appearance of domestic normalcy. Friedel’s emotional rigidity becomes most visible after Otto’s arrest, as she refuses to accept responsibility or doubt the cause they served.

Her faith in Germany’s eventual victory and her pressure on her children to remain aligned with that vision reveal a woman who clings to ideology as a source of meaning, even when it brings suffering to her family.

Ruth Kuehn

Ruth Kuehn represents the contradictions and vulnerabilities within the family’s story. Raised within Nazi structures, she is socialized into a culture that rewards loyalty and punishes deviation, yet her own heritage places her in danger under the very laws she lives by.

Her involvement in gathering information through social relationships with military officers shows how personal charm and intimacy become tools of political work.

Ruth’s earlier relationship with a powerful Nazi official highlights how proximity to power offers temporary protection while also exposing her to manipulation and risk. Her later life, marked by fractured relationships and public exposure of her family’s role in espionage, reveals the personal cost of growing up in a world where identity, survival, and ideology are tightly bound together.

Hans Kuehn

Hans Kuehn’s character reflects the experience of a child shaped by circumstances far beyond his control. Growing up within a family embedded in espionage and later facing internment, he experiences instability, illness, and neglect. His vulnerability is intensified by the collapse of normal family life after Otto’s arrest, as caretaking arrangements fail to provide safety or consistency.

Hans’s suffering highlights how the consequences of political choices made by adults fall heavily on children, who bear emotional and physical costs without understanding the forces at work. His story adds a human dimension to the broader historical narrative, showing how state actions and family ideology translate into intimate harm.

Leopold Kuehn

Leopold Kuehn, the son who remains in Germany, represents the branch of the family that fully commits to Nazism. His rise within the Nazi hierarchy and his enthusiastic expressions of loyalty to Hitler contrast sharply with Eberhard’s eventual rejection of the regime.

Leopold’s character underscores how the same upbringing can produce radically different outcomes depending on temperament, opportunity, and belief. His continued identification with the regime, even as it becomes increasingly brutal, illustrates how ideological commitment can harden into identity, making moral reversal difficult.

Leopold serves as a reminder that the family’s story is not only about coercion and survival but also about active participation in a system of persecution.

Takeo Yoshikawa

Takeo Yoshikawa functions as a professional intelligence officer whose actions reveal the disciplined, methodical side of wartime espionage. Unlike Otto, whose motivations are entangled with personal grievance and financial gain, Yoshikawa operates within a strict military and cultural code.

His careful observation of Pearl Harbor, use of public vantage points, and cultivation of information networks reflect a strategic mindset focused on preparation rather than improvisation. Yoshikawa’s character illustrates how individual operatives fit into larger state machinery, translating everyday observations into data that feed strategic decisions.

His role emphasizes that the attack on Pearl Harbor was not the product of a single betrayal but of sustained, organized intelligence work.

Robert Shivers

Robert Shivers, the FBI agent assigned to monitor espionage activity in Hawaii, represents the limits of law enforcement in the face of political constraints and incomplete evidence.

His growing suspicion of the Kuehn family and Japanese diplomatic staff shows a perceptive understanding of the threat environment, yet he is constrained by legal standards and institutional caution.

Shivers’s frustration reflects the broader failure of U.S. intelligence agencies to act decisively on warning signs before the attack. His character highlights the tension between vigilance and proof, illustrating how bureaucratic processes and underestimation of risk can blunt even serious concerns.

Analysis of Themes

Silence, Secrecy, and the Inheritance of Trauma

Silence operates as both a shield and a wound throughout Family of Spies, shaping relationships across generations and determining how pain is transmitted within families. The older generation hides its past not simply to avoid legal consequences but to protect itself from shame, fear, and social ruin.

Otto and Friedel’s choices require secrecy to survive, and that secrecy becomes a family practice long after the war ends. For Eberhard, silence becomes a survival strategy in the United States, where his family’s history threatens his identity and safety. His reluctance to speak is rooted in direct experience: when he once shared the truth, it was used against him in moments of conflict.

As a result, silence hardens into habit, and habit becomes inheritance. Christine grows up sensing gaps in her family narrative, absorbing unease without understanding its source. This shows how trauma can pass through generations not only through stories told but through stories withheld. The absence of truth shapes emotional life just as strongly as disclosure might have.

Silence also creates distortions of identity, forcing descendants to construct themselves around partial narratives. When Christine finally uncovers the full history, the emotional impact is not limited to learning facts; it lies in recognizing how much of her family’s emotional world was organized around avoidance.

The theme highlights how secrecy offers temporary protection while creating long-term harm, leaving later generations to face the consequences of choices they did not make but must still carry.

Moral Complicity and Personal Responsibility

Moral responsibility in Family of Spies is presented as a series of choices made within constrained circumstances, rather than as abstract alignment with ideology alone. Otto’s involvement with Nazism and later with Japanese intelligence is shaped by ambition, resentment, and the promise of restored status.

These motives do not excuse his actions, but they complicate any attempt to portray him as a simple villain. Friedel’s loyalty to her husband and belief in the regime’s future reveal how complicity often grows out of emotional dependence and a desire for stability. The family’s participation in espionage demonstrates how ordinary domestic life can coexist with acts that contribute to mass harm. Hosting parties, running small businesses, and maintaining social ties become part of a structure that feeds military intelligence.

The book also raises questions about responsibility for those who grow up within such systems. Ruth’s involvement in gathering information and Eberhard’s childhood exposure to the family’s work show how young people are socialized into moral frameworks before they can fully assess them. Later, Eberhard’s rejection of Nazism and service in the U.S. Army suggests that moral agency can reassert itself, even after formative years shaped by harmful ideologies.

The theme insists that responsibility is neither erased by circumstance nor easily assigned in neat categories. It examines how people justify actions to themselves, how loyalty to family can conflict with loyalty to broader moral principles, and how accountability remains even when individuals act within powerful political currents.

Identity, Belonging, and the Pressure of Ideology

Identity in Family of Spies is shown as unstable under the pressure of ideology, nationality, and shifting political realities.

Otto’s sense of self is tied to lost status after World War I, making him susceptible to movements that promise renewal and recognition. Nazism offers him not only political alignment but a restored sense of belonging and purpose. Friedel adopts this identity alongside him, finding meaning in loyalty to a cause that claims to elevate the nation and, by extension, their family. For Ruth, identity is more conflicted.

Raised within Nazi culture yet carrying a background that places her in danger under racial laws, she lives with constant tension between who she is told she should be and who she is in the eyes of the regime. This conflict exposes how ideological systems create rigid categories that can trap individuals in impossible positions. Eberhard’s experience in the United States adds another layer to the theme. As a German-born child raised in an espionage household, he later attempts to construct an American identity that distances him from his family’s past.

Citizenship and military service become tools for self-definition, yet the shadow of his origins continues to shape how he sees himself and how others might see him if the truth were known. Christine’s later investigation reflects a search for identity through history, as understanding her family’s past becomes part of understanding her own place in the world.

The theme shows how belonging is often negotiated under pressure, with ideology offering certainty while demanding conformity that can fracture personal identity.

The Collision of Private Lives and Global History

Private family life in Family of Spies unfolds within the force field of global conflict, demonstrating how large historical events invade intimate spaces and reshape personal destinies. The Kuehn household is not merely affected by war; it becomes one of the small sites through which war is prepared.

Social gatherings, romantic relationships, and business ventures serve as channels for intelligence work, turning everyday interactions into acts with geopolitical consequences. This collision between private and public worlds reveals how history is not only made by generals and politicians but also by families whose choices accumulate into broader outcomes.

The children experience the effects of these choices in deeply personal ways, through displacement, internment, and the breakdown of family bonds. After the attack on Pearl Harbor, state power enters the family’s life through arrests, secret trials, and detention camps, replacing the illusion of control with abrupt vulnerability. The theme also extends across time, as Christine’s contemporary life is shaped by archival discoveries and long-hidden records.

Her present is altered by events that occurred decades before she was born, showing how historical actions continue to structure personal realities long after the immediate crisis has passed. The book thus frames global history not as a distant backdrop but as a force that rearranges family structures, relationships, and self-understanding. It presents history as something that enters living rooms, marriages, and childhoods, leaving marks that endure across generations.