Final Cut by Olivia Worley Summary, Characters and Themes

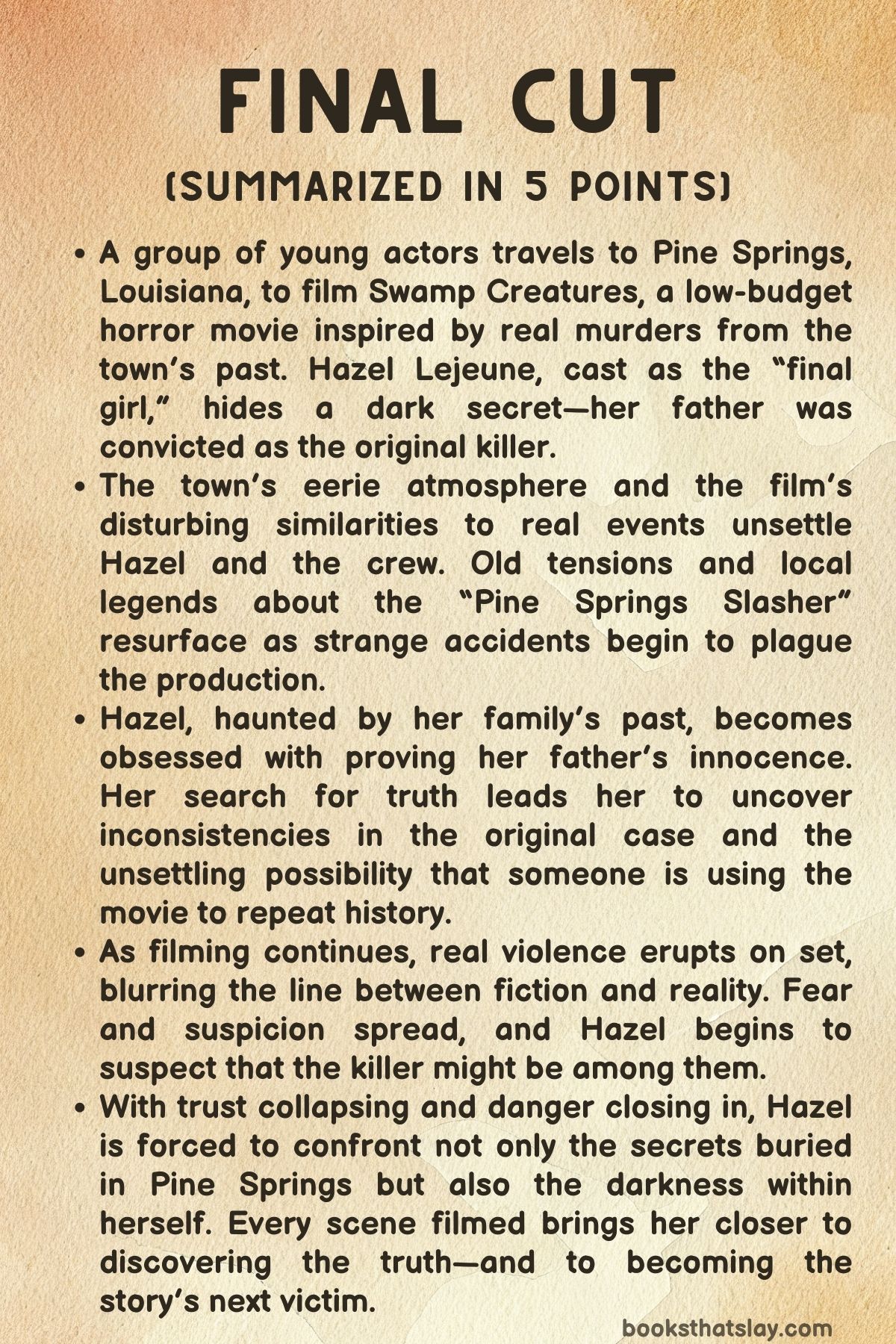

Final Cut by Olivia Worley is a chilling psychological thriller that blends the conventions of slasher cinema with the tension of true-crime mystery. Set in the eerie Louisiana town of Pine Springs, the story follows Hazel Lejeune, a young actress cast in a low-budget horror film based on real murders committed by her father years earlier.

As the production unfolds, life begins to imitate art—actors vanish, fake blood turns real, and Hazel must confront the truth behind her family’s past. Through shifting suspicion, meta-horror commentary, and a slow-burning unraveling of secrets, the novel explores guilt, identity, and the dark allure of storytelling.

Summary

The novel opens with a chilling prologue: a woman posing as a film crew member lures a man into the woods under the guise of signing paperwork, then films his brutal murder. She coolly remarks that breaking genre rules is the way to master them.

This sets the tone for a story where cinema and reality bleed together.

Soon after, an audition notice appears for Swamp Creatures, a horror film about teens hunted by a masked killer in a Louisiana swamp. Among the applicants is Hazel Lejeune, a young woman desperate to escape her past.

Fifteen years earlier, her father, Cal Dupre, was convicted as the “Pine Springs Slasher” for murdering five students. The tragedy destroyed Hazel’s family and turned their names into a local legend.

Determined to reclaim her identity, Hazel accepts the lead role of Sam—the film’s “final girl”—even though filming takes place in Pine Springs, the town she vowed never to return to.

Upon arrival, Hazel checks into a decrepit motel whose flickering sign eerily reads “WELCOME GHOSTS.” The locals treat her with unease, and though no one recognizes her, the town’s dark memory hangs heavy. Her fellow cast members include Cameron, her on-screen boyfriend; Nina, an upbeat horror enthusiast; Brooke, the confident “mean girl”; and Lucas, the excitable film buff.

The production’s director, Autumn Smith, and her girlfriend, Wren, insist on secrecy about the script’s ending—no one knows who the killer is, even within the movie.

The first day of filming at Pine Springs High School—the real site of the original murders—rekindles Hazel’s buried trauma. The building’s halls are frozen in time, echoing the crimes her father supposedly committed.

During shooting, the crew discovers a mutilated rabbit in the hallway, an omen that unsettles everyone. Hazel hides her panic, confiding only in Nina, who becomes her closest ally.

That evening, the cast visits the Pine Springs Mystery Museum, run by an eccentric curator named Claude. Among dusty relics and swamp folklore, Claude reveals an exhibit about the Pine Springs Slasher.

To Hazel’s horror, the victims’ names and faces mirror the characters in Swamp Creatures. The parallels suggest the film’s script was inspired directly by the murders.

Claude hints that Cal Dupre’s confession was suspicious and possibly coerced, sparking Hazel’s doubt about her father’s guilt.

Back at the motel, Hazel secretly researches her father’s case, uncovering inconsistencies but no clear answers. The next day, filming resumes, but danger creeps closer.

During a classroom scene, a light fixture nearly crushes Nina, narrowly missing her. The incident is dismissed as an accident, yet Hazel senses deliberate malice.

Her unease deepens when she receives mysterious phone calls from an unknown number.

The production moves to the swamp, where the atmosphere thickens with dread. While filming a death scene, Brooke, one of the actresses, is stabbed for real.

The crew descends into chaos as Hazel realizes the prop knife was swapped with a real one. Though Brooke survives, the police investigation yields no suspects, and the shoot continues under dubious explanations.

Hazel confides in Cameron and Nina, suspecting someone on set is reenacting the original killings. The three, joined by Lucas, begin investigating on their own, discovering rumors about another suspect—a janitor named Skeet Bergeron—who still lives in the swamp.

The townspeople warn them to stop digging, but their curiosity only grows.

Soon after, tragedy strikes again. The makeup artist, Tammy, is found dying in the woods with her throat slashed.

Moments later, Hazel and Cameron stumble upon the butchered remains of Harry, another crew member. The horror intensifies when news breaks that Brooke, recovering in the hospital, has been murdered.

The police suspect the killer is among the film crew. Hazel’s worst fears come true when Officer West, assigned to protect them, and another crew member are also found dead.

As panic spreads, Hazel confesses to her friends that she is Cal Dupre’s daughter. Shocked but loyal, they agree to help her uncover the truth.

Soon they receive a blood-stained copy of the Swamp Creatures wrap-party invitation—scheduled for the anniversary of the original murders. A video camera found at a crime scene shows one of their missing crew members, Kyle, bound and terrified in Skeet Bergeron’s swamp house.

Despite the risks, Hazel and Cameron decide to rescue him, rowing through the misty bayou while Nina and Lucas wait for help. But before they can reach the boat, the killer ambushes the group, attacking Nina and Lucas.

In the final act, Hazel awakens bound inside a decrepit shack. Standing before her is Evan, the film’s cinematographer.

He reveals himself as the true killer and mastermind. Evan explains his twisted past: years ago, he was one of Cal Dupre’s students and film-club members.

Cal encouraged his obsession with horror, but their mentorship turned sinister when Cal accidentally killed a student named Susie Trahan. Evan helped him cover it up by murdering other students to frame a slasher narrative.

Cal, guilt-ridden, took the blame and confessed, shielding Evan. Abandoned afterward, Evan devoted his life to recreating their “story,” seeking vengeance by drawing Hazel into his final film.

Evan’s accomplice, Lucas, reappears alive, admitting he helped orchestrate the murders. Together, they plan to film Hazel’s death as the finale of their masterpiece.

Evan hands Hazel a knife, demanding she kill her surviving friends for the camera. Pretending to obey, Hazel instead frees Nina and fights back.

In a brutal struggle, Hazel kills Evan while Nina shoots Lucas. As Evan dies, he smirks, declaring Hazel his true “final girl.”

Afterward, Hazel is questioned by Detective Jones, the same officer who once arrested her father. Lucas confesses to everything, and the police confirm Evan’s elaborate deception.

Hazel secretly erases the final footage of Evan’s death, unwilling to let anyone exploit it again. Her mother, Sadie, arrives, revealing that she always suspected Cal’s guilt but urged him to confess to protect Hazel.

Sadie admits Cal’s abuse and manipulative nature, helping Hazel finally understand the full truth.

In the aftermath, Hazel visits Nina, Autumn, and Wren at town hall, where they reflect on the horror they’ve survived. Autumn confesses her own guilt—she once threatened to expose Cal years ago, triggering events that spiraled into tragedy.

Despite everything, Hazel realizes she’s broken the cycle of silence and fear. As she prepares to leave Pine Springs with her mother, she receives a call from her father in prison.

This time, she answers, ready to face him—not as a victim or an actress, but as someone who’s taken control of her own story.

Characters

Hazel Lejeune

Hazel Lejeune is the emotional and moral center of Final Cut—a young woman haunted by the crimes of her father, Cal Dupre, the infamous “Pine Springs Slasher.” Her journey is one of reclamation and confrontation: she returns to the town that destroyed her family, not merely to act in a film based on its tragedy but to rewrite the narrative that has defined her life. Haunted by inherited guilt and the public’s fascination with her father’s sins, Hazel embodies the archetype of the modern “final girl”—a survivor not just of external horror but of internalized trauma.

Her obsession with slasher films reflects her desire for control over chaos; she sees survival as a form of authorship. As events spiral and the killings begin again, Hazel’s resilience, intelligence, and compassion come to the forefront.

Her eventual confrontation with Evan reveals the depths of her courage—facing not only physical danger but the psychological inheritance of violence. By the novel’s end, Hazel has embraced her complexity: she is neither victim nor villain but a flawed, fierce young woman reclaiming her agency from her father’s shadow.

Cal Dupre

Cal Dupre, once a beloved teacher, becomes a haunting symbol of corruption, secrecy, and generational trauma. Though imprisoned for years as the “Pine Springs Slasher,” his guilt remains shrouded in ambiguity until the horrifying truth emerges: his accidental killing of Susie and his complicity in Evan’s crimes.

Cal’s duality—mentor and monster, father and killer—casts a long shadow over every aspect of Hazel’s life. His manipulation of Evan, born from his own warped fascination with horror and voyeurism, reveals a mind drawn to the performance of violence as much as to the act itself.

Cal’s eventual exposure does not redeem him; rather, it humanizes the terror he represents. Through Hazel’s reckoning with her father, the novel examines how evil often thrives in ordinary forms and how the line between influence and indoctrination can blur dangerously.

Evan

Evan is both the physical antagonist and the thematic embodiment of obsession in Final Cut. A former student of Cal Dupre, he becomes a chilling reflection of what happens when fascination with violence turns into identity.

Evan’s admiration for Cal mutates into imitation and vengeance; he crafts his own “film” of death to immortalize himself and punish those who abandoned him. His self-perception as an artist—“directing” real murders as cinematic acts—blurs morality and artifice in a deeply unsettling way.

Yet, beneath his bravado lies profound emptiness: a child molded by neglect and twisted mentorship. His fixation on Hazel is both revenge and perverse homage, seeing her as the ultimate proof of his—and Cal’s—legacy.

His death at Hazel’s hands completes the cycle he began, transforming her unwillingly into the final girl he idolized.

Nina Rivera

Nina Rivera stands as Hazel’s emotional anchor and moral counterpoint. Passionate about horror films but grounded in empathy, she offers warmth and humor that contrast sharply with the bleakness around them.

Nina’s friendship with Hazel deepens through shared curiosity and fear, evolving into sisterly loyalty. Unlike Hazel, Nina approaches horror as entertainment, not therapy, yet her courage during the climax reveals unexpected depth.

She not only fights back but helps Hazel break free from the destructive legacy that traps her. Nina’s survival is a quiet triumph—proof that kindness and courage can coexist even in the darkest settings.

Cameron Cormier

Cameron Cormier, Hazel’s co-star and love interest, serves as both emotional catalyst and tragic mirror. His connection to the original victims—being Reeve’s brother—ties him to Hazel in a web of inherited trauma.

Their relationship blurs the line between performance and reality, forcing both to confront pain disguised as art. Cameron’s initial skepticism evolves into genuine belief and loyalty; his near-death experience underscores the randomness of survival in horror, but his ultimate endurance provides hope.

Through Cameron, the novel explores love as both vulnerability and defiance—a rare tenderness amid exploitation and death.

Wren Olivera

Wren Olivera, the assistant director and Autumn’s partner, represents the pragmatic side of filmmaking and the moral uncertainty of art inspired by tragedy. Dedicated and composed, she initially appears as a stabilizing force, but her insistence on continuing production despite danger reveals the industry’s dark allure—the prioritization of story over safety.

Wren’s relationship with Autumn adds emotional texture, showing how creative ambition can both bond and blind. She becomes a subtle symbol of complicity, embodying how people rationalize horror when it serves their art.

Autumn Smith

Autumn Smith, the director of Swamp Creatures, is a complex figure burdened by guilt and artistic obsession. Her decision to make a film based on the Pine Springs murders stems from a desire to atone—having anonymously threatened to expose Cal years earlier—but also from a fascination with tragedy as art.

Autumn’s secrecy, intensity, and drive blur ethical boundaries; she both exploits and mourns the past. By the novel’s end, her confession reframes her motives, revealing that creation and confession can be two sides of the same need: to control what once terrified you.

Sadie Lejeune

Sadie, Hazel’s mother, embodies the long-term cost of surviving proximity to evil. A woman who has spent years fleeing her husband’s legacy, she represents the silent victims left behind after public horror fades.

Her relationship with Hazel is strained but deeply loving; she hides truths to protect her daughter, even convincing Cal to plead guilty to end the cycle of exposure. Sadie’s late confession—that Cal was abusive long before the murders—redefines the story not as one of mystery alone but of domestic violence and endurance.

Her final reconciliation with Hazel marks the emotional resolution of Final Cut, grounding its blood-soaked narrative in maternal love and resilience.

Chief Amos Carpenter

Chief Carpenter personifies the institutional blindness that allows horror to persist. His quick dismissal of evidence and reliance on old conclusions reveal the town’s unwillingness to confront its own complicity.

Though not a villain in the traditional sense, his complacency and adherence to myth perpetuate injustice. Carpenter represents the broader societal instinct to simplify evil—to name one monster and move on, rather than examine the rot beneath.

Lucas Murphy

Lucas Murphy, the young actor turned accomplice, is a study in manipulation and moral decay. Initially portrayed as an eager film buff, his transformation into Evan’s ally exposes the seductive nature of narrative control—how easily fascination with violence becomes participation in it.

Lucas’s confession to killing his father and aiding Evan underscores the theme of generational corruption and the fragility of morality when identity is built around horror. His final capture contrasts sharply with Hazel’s survival, illustrating the diverging paths of those drawn to darkness: one consumed by it, the other mastering it.

Themes

Identity and Legacy

Hazel’s journey in Final Cut is rooted in her struggle to define her own identity while bearing the shadow of her father’s legacy. Branded as the daughter of Cal Dupre—the infamous Pine Springs Slasher—she is trapped between inherited guilt and the yearning to reclaim control over her narrative.

Her decision to return to Pine Springs and act in a movie inspired by her father’s crimes is both an act of defiance and reclamation. She seeks to rewrite the story that has haunted her life, yet her immersion in a world built on performance and imitation blurs the boundaries between who she is and who others perceive her to be.

Hazel’s internal conflict illustrates the heavy burden of lineage and the difficulty of separating oneself from a family’s sins. Her discovery of Cal’s true involvement in the murders—his guilt and his silence—deepens her crisis.

She must confront the uncomfortable reality that evil may not be a simple inheritance but a reflection of human weakness and choice. Her final confrontation with Evan and her moment of violent survival serve as a painful assertion of identity.

By killing him, she does not merely avenge the past; she symbolically ends her father’s legacy. Yet her fear that she might share his darkness lingers, demonstrating that identity, especially one born from trauma, is a continuous process of negotiation rather than resolution.

Performance and Reality

The film’s production acts as a mirror through which Final Cut examines the blurred lines between performance and reality. The set of Swamp Creatures is not just a backdrop for horror but a metaphor for how people construct and consume narratives.

The characters—actors playing victims—are unwittingly reenacting real murders, turning art into a grotesque echo of life. Hazel, as both an actress and a survivor of her father’s crimes, exists in a constant state of duality; her performances are indistinguishable from her real fears.

Olivia Worley uses the filmmaking process to critique the entertainment industry’s obsession with true crime and the exploitation of tragedy for spectacle. Each scene filmed becomes an uncanny repetition of trauma, forcing Hazel to question whether truth can ever exist in a world obsessed with retelling and dramatizing horror.

The murderer, Evan, takes this obsession to its extreme—he treats murder as art, seeking to immortalize himself through film. His desire to capture death on camera exposes the disturbing intersection of creation and destruction.

In contrast, Hazel’s final act of destroying the footage is a reclamation of agency, rejecting the commodification of pain. Through this theme, the novel questions authenticity, morality, and the human impulse to mask truth behind performance.

Guilt and Redemption

Guilt permeates every character in Final Cut, shaping their decisions and relationships. Hazel carries generational guilt, haunted by her father’s crimes and her mother’s secrecy.

Her mother’s silence, born from shame and fear, mirrors Hazel’s own self-imposed isolation. As the narrative progresses, guilt transforms from a passive burden into a motivating force that drives Hazel toward the truth.

Her quest is not only to prove her father’s innocence but to free herself from the emotional paralysis of inherited sin. When she learns that her father did commit part of the crimes and shielded the real killer, Evan, her sense of guilt morphs into anger and betrayal.

The revelation forces her to confront the complexity of morality—people can be both victims and perpetrators. Redemption, for Hazel, comes not from forgiveness but from choice.

She decides to confront violence rather than run from it, and her survival becomes an act of moral clarity. Her mother’s confession that she encouraged Cal’s guilty plea “to protect Hazel” adds another layer—redemption is often tainted by sacrifice.

By the end, Hazel’s decision to destroy the footage and face her father’s call represents her acceptance of imperfection and her refusal to let guilt define her future.

The Exploitation of Violence

A central tension in Final Cut lies in its portrayal of how violence is consumed, replicated, and exploited. The film crew’s willingness to reenact real murders for entertainment exposes a disturbing fascination with death.

Through the fictional movie Swamp Creatures, the novel critiques the commodification of human suffering and society’s desensitization to brutality. Hazel’s discomfort with the project stems not only from personal trauma but from an ethical awareness that art can easily cross into exploitation.

Evan, who manipulates the production to stage real killings, embodies this perverse fascination—he sees murder as performance, the ultimate form of artistic control. His obsession reveals how easily aesthetic ambition can devolve into moral decay.

By turning the camera into a weapon, Worley underscores how recording transforms violence into something palatable and permanent. The story ultimately condemns this exploitation by contrasting Evan’s desire for cinematic immortality with Hazel’s refusal to let tragedy become spectacle.

In destroying the film, Hazel rejects the voyeuristic consumption of pain and reclaims ownership of her story. The theme extends beyond the characters, challenging readers to reflect on their own complicity in a culture that glamorizes horror.

Trauma and Survival

Trauma operates as both a haunting and a catalyst in Final Cut. Hazel’s life is built upon suppressed memory, inherited fear, and the scars of public judgment.

Her return to Pine Springs reopens emotional wounds, forcing her to relive the site of her father’s crimes. Yet, through this confrontation, trauma evolves into resilience.

Each terrifying incident on set—the knife attack, the murders, the revelations—forces Hazel to navigate fear not as a victim but as a survivor reclaiming her agency. Olivia Worley portrays trauma as cyclical, reemerging through reenactment, memory, and even art.

The film production acts as a symbolic therapy session gone wrong, where buried emotions manifest through horror. Hazel’s transformation into the “final girl” is more than genre convention; it is a psychological evolution.

She learns that survival is not the absence of pain but the decision to continue despite it. The story closes with Hazel accepting the full truth of her father’s crimes, confronting his call, and choosing to live with knowledge rather than denial.

Her survival does not erase trauma—it integrates it into a new sense of self. The theme ultimately speaks to endurance: the ability to rebuild meaning from the ruins of violence and fear.