Finding My Way Summary and Analysis

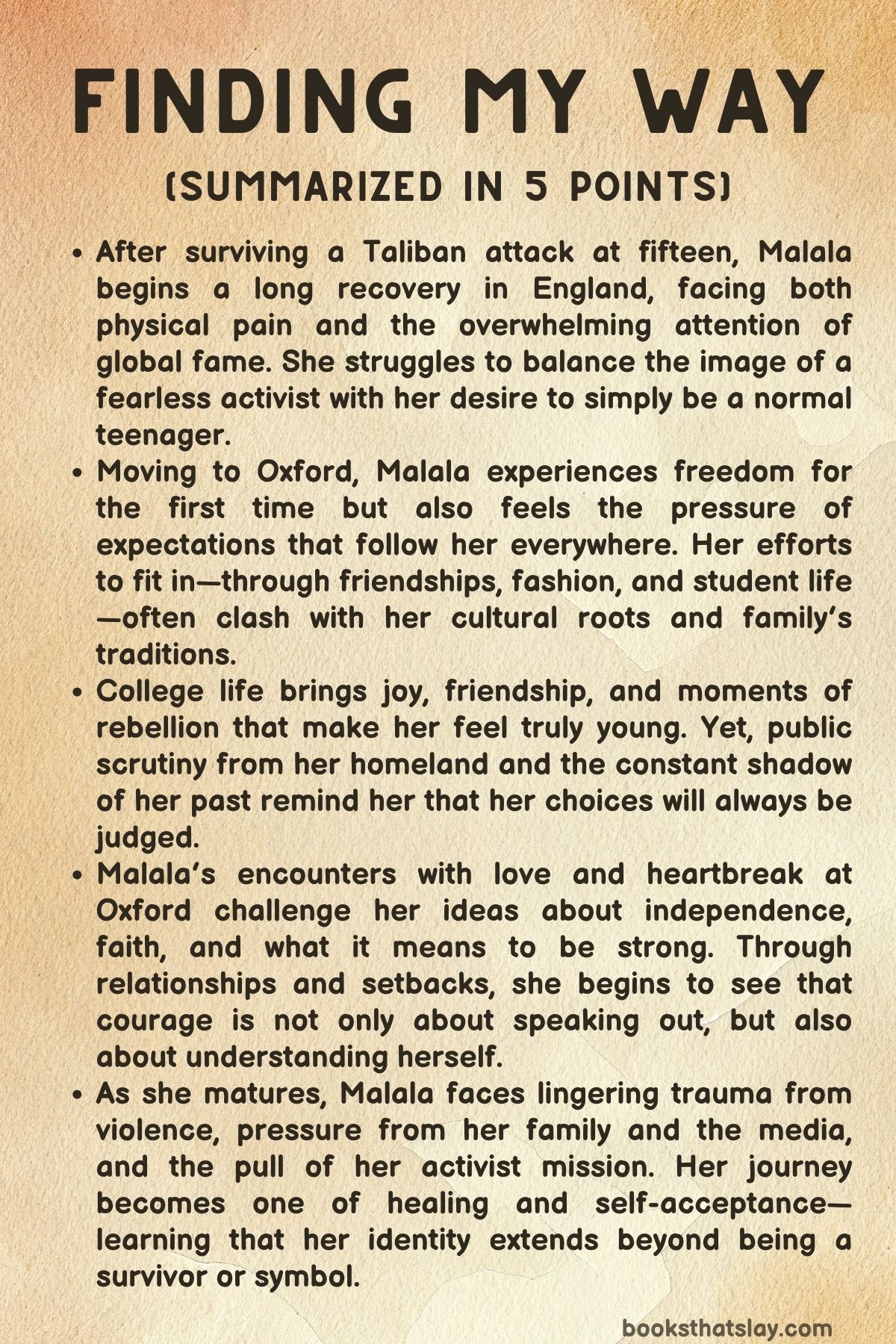

Finding My Way by Malala Yousafzai is an inspiring continuation of her journey beyond the events that first brought her to global attention. Known worldwide as the girl who survived a Taliban bullet and went on to win the Nobel Peace Prize, Malala here offers an intimate, reflective portrait of life after heroism.

The book explores her struggle to reclaim normalcy amid the burden of fame, her experiences as a student at Oxford, her friendships and heartbreaks, and her gradual understanding of identity, love, and purpose. It is a deeply personal narrative of growth, resilience, and the ongoing search for belonging in a divided world.

Summary

The story opens with Malala Yousafzai reflecting on the aftermath of the attack that changed her life. At fifteen, she was shot by the Taliban for standing up for girls’ education in Pakistan’s Swat Valley.

After surviving the near-fatal injury and being taken to Birmingham, she woke up in a foreign country, facing both physical pain and a strange new identity as an international symbol of courage. While the world celebrated her bravery, she struggled internally—caught between being seen as a saintly figure and longing for the simple life of a teenage girl who loved school, friends, and laughter.

In England, Malala faced a new challenge: adapting to a completely different environment. The language, the culture, and her medical recovery made it difficult to fit in.

She felt isolated and often failed in her early school exams. Missing her old classmates and her familiar life in Pakistan, she found the transition harsh.

Over time, through persistence, she made her first real friend, Alice, but still felt out of place. The memories of her old friends and the solidarity they shared under threat of the Taliban haunted her, even as she prepared to move to Oxford University.

At Oxford, Malala began to rediscover herself. She experienced independence for the first time, though still accompanied by security officers for protection.

Determined to make the most of her university life, she joined clubs, met new people, and attended events. She befriended Cora, another student studying Philosophy, Politics, and Economics, who treated her like any other peer.

This friendship gave Malala a rare sense of normalcy. Soon, she expanded her circle with Hen from Zimbabwe, Yasmin from Iran, and Anisa from India.

Together, they formed a close-knit group, sharing meals, laughter, and adventures that helped Malala feel young and free again.

However, freedom came at a cost. When a photo of her in jeans went viral, conservative voices in Pakistan erupted in outrage, condemning her attire as disrespectful to her culture.

Her parents, particularly her mother, were upset, but Malala stood firm, asserting her right to choose her own clothes. She realized that no matter what she did, people would judge her.

This incident deepened her understanding of the double standards women face and strengthened her resolve to live authentically.

Amid her growing independence, academic pressure and activism collided. Between global speaking engagements and her demanding coursework, she found herself exhausted and guilty for missing classes.

Yet, her activism supported her family financially, a responsibility she could not ignore. Even as she advocated for millions of girls’ education, she longed for the simplicity of being just another student.

Within her friend group, she became the one others turned to for advice, even about relationships—despite her own inexperience and insecurities about love and appearance.

Her curiosity about love took shape when she met Tarik, a mysterious Moroccan student known for his troubled past. Drawn to his quiet presence and defiance, she felt an inexplicable connection.

They shared a few intimate moments—late-night talks, secret meetings at the college bell tower—but their relationship was unbalanced. Tarik was distant, unpredictable, and burdened by personal issues, while Malala projected her longing for affection and understanding onto him.

When he eventually disappeared from Oxford, she realized she had been more in love with the idea of rescuing him than with the person himself. This realization helped her confront her loneliness and understand her emotional boundaries.

As she continued her studies, Malala found herself reconnecting with her roots. She began attending gatherings of Pakistani students and rediscovered the joy of her language, culture, and music.

These experiences helped her heal the divide between her Pakistani identity and her life in the West. Overcome by nostalgia, she decided to return home for the first time since the attack.

The visit was both emotional and cathartic. She visited her old house, reunited with her childhood friend Moniba, and met her ailing grandmother.

The trip allowed her to make peace with her past and accept both loss and growth.

Returning to England, Malala continued to balance her activism with her studies. During this time, she met Asser, a compassionate and thoughtful friend who would later become her husband.

Their relationship began quietly, built on trust and mutual respect. After facing anxiety and emotional challenges, Malala confided in Asser, finding in him a sense of safety and understanding she had long craved.

Their bond deepened through shared conversations about faith, love, and purpose.

However, her relationship with Asser also caused conflict at home. Her parents, especially her mother, were uneasy about her dating, fearing it went against their cultural values.

Despite initial tension, Malala stood by her choices, navigating her family’s expectations and her own independence. Their eventual meeting was awkward but marked by mutual respect.

The relationship grew slowly, enduring distance, personal challenges, and public scrutiny.

At the same time, Malala struggled with her mental health. Academic pressure, loneliness, and unresolved trauma from the shooting culminated in severe anxiety and panic attacks.

With the help of therapy, she began to process her experiences, learning to manage her fears and understand her emotional triggers. Through counseling, she rebuilt her sense of self and found renewed strength.

Her journey through Oxford concluded during the COVID-19 pandemic, which forced her to finish her degree from home. The lockdown rekindled family tensions but also brought moments of warmth and rediscovery.

When she graduated with a degree in Philosophy, Politics, and Economics, she felt she had achieved something extraordinary—not just academically but personally. The girl who had once been silenced by violence had reclaimed her voice on her own terms.

Asser’s family later met hers, and after much reflection, Malala agreed to marry him in a simple ceremony at home in 2021. Despite cultural criticism and social media backlash, she embraced her decision, sharing her happiness openly.

Married life brought her contentment and balance. She continued her advocacy for girls’ education, supporting Afghan women during the Taliban’s return to power and visiting the school she built in Shangla.

Standing before hundreds of girls learning freely, she felt her mission had come full circle.

In the end, Finding My Way captures Malala’s evolution from survivor to woman, from a global icon to a person still discovering her place in the world. Through pain, faith, love, and resilience, she learns that true freedom lies not in escaping her past, but in embracing every part of it.

Key People

Malala Yousafzai

In Finding My Way, Malala Yousafzai emerges as a deeply introspective narrator, navigating the complex intersection between public heroism and private identity. Once a symbol of global courage after surviving the Taliban’s attack, she now confronts the suffocating expectations that fame imposes.

Beneath her public image as a Nobel laureate and advocate lies a young woman longing for ordinary experiences—friendship, love, and freedom. At Oxford, Malala learns independence and self-expression, confronting societal judgment and internalized fear.

Her evolution is both emotional and philosophical: she questions tradition, love, faith, and self-worth while balancing her family’s dependence and her personal desires. Through heartbreaks, cultural dilemmas, and mental health struggles, she matures into a woman who claims ownership of her narrative.

By the end of the book, Malala achieves peace—a harmony between her Pashtun roots and her Western education, between advocacy and individuality. She embodies resilience not just as a survivor of violence, but as a seeker of self-acceptance and balance.

Ziauddin Yousafzai

Ziauddin, Malala’s father, is portrayed as both an inspiring figure and a source of emotional conflict. A teacher and activist himself, he instills in Malala the belief that education is sacred and that equality must be fought for.

Yet, as her fame grows, his protective instincts clash with her desire for autonomy. His pride in his daughter’s success coexists with cultural conservatism that often limits her independence, especially regarding her social life and romantic choices.

When Malala begins exploring her individuality—wearing jeans, forming friendships with boys, or expressing doubts about marriage—Ziauddin’s idealism is tested by paternal concern. Despite disagreements, his love remains steadfast, and his eventual acceptance of Asser shows his willingness to evolve.

Ziauddin represents a bridge between tradition and progress, a man caught between the values of his homeland and the freedom his daughter embodies.

Toor Pekai Yousafzai

Malala’s mother, Toor Pekai, provides a strong emotional anchor in the narrative. Deeply rooted in Pashtun culture, she embodies faith, humility, and devotion to family.

However, her traditional worldview often collides with Malala’s liberal environment in England. Her insistence that her daughter wear shalwar kameez and marry a Pashtun man reflects her fear of losing cultural identity.

Yet she also undergoes transformation—discovering her own independence in Birmingham, learning English, and embracing a more confident self. Her relationship with Malala oscillates between tenderness and tension, mirroring the generational and ideological gap between them.

Ultimately, Toor Pekai’s love transcends disagreement; she becomes a quiet force of acceptance, illustrating that motherhood, like freedom, evolves through understanding.

Tarik

Tarik serves as an emotional catalyst in Malala’s journey toward self-awareness. Mysterious and self-destructive, he represents both danger and vulnerability—a mirror to Malala’s suppressed longing for emotional connection.

Her attraction to him is less romantic and more symbolic: she is drawn to his brokenness, believing she can heal it, much like she wishes to heal the world. Tarik’s instability—his rumored involvement in drugs, his isolation, his anger—contrasts with Malala’s discipline and compassion.

Yet, his presence exposes her naivety, teaching her painful lessons about boundaries, illusion, and the futility of rescuing those unwilling to change. When Tarik disappears, Malala is left with introspection rather than heartbreak, realizing that love must begin with self-respect.

Through Tarik, she confronts her vulnerability and learns to navigate desire without losing herself.

Asser

Asser enters the narrative as a source of steadiness, empathy, and equality—the antithesis of Tarik. Intelligent, kind, and progressive, he treats Malala not as a symbol, but as a woman with fears, flaws, and emotions.

Their relationship grows through emotional honesty, built on shared values rather than infatuation. Asser’s patience and humor balance Malala’s intensity, helping her rediscover trust and joy.

Yet, their love also tests her autonomy; cultural and familial expectations resurface, forcing her to reconcile personal freedom with commitment. Asser’s genuine affection, his support during public controversies, and his understanding nature make him both partner and ally.

Their eventual marriage represents not submission to tradition, but the evolution of love on her terms—a partnership rooted in equality and mutual respect.

Cora, Hen, Yasmin, and Anisa

These friends collectively symbolize Malala’s re-entry into ordinary youth and companionship. Cora’s warmth and acceptance allow Malala to feel seen beyond her fame.

Hen’s boldness and humor challenge her to loosen control and embrace spontaneity. Yasmin’s shared refugee identity creates a bond of empathy and shared resilience, while Anisa’s intellect and assertiveness push Malala to question her assumptions about success and privilege.

Together, they form the emotional tapestry of Oxford life, offering both comfort and conflict. Through laughter, misunderstanding, and reconciliation, they reflect Malala’s gradual transformation from isolation to belonging.

Their friendships ground her humanity, reminding her that growth often comes through connection rather than solitude.

Farida

Farida, Asser’s mother, is portrayed as graceful, articulate, and emotionally perceptive. Her elegance and warmth disarm Malala’s initial anxiety, and their meeting foreshadows a nurturing, rather than controlling, maternal presence in Malala’s married life.

Farida’s stories about Asser’s childhood and her emotional openness humanize her, breaking Malala’s preconceived notions about in-laws and traditional expectations. She represents maternal love free from rigidity—embodying a blend of cultural pride and modern empathy.

Her relationship with Malala offers a glimpse into intergenerational understanding and compassion.

Evelyn

Evelyn, Malala’s therapist, plays a quiet yet transformative role in the latter part of Finding My Way. She helps Malala confront the unspoken trauma of violence, fame, and emotional repression.

With patience and wisdom, Evelyn provides the tools Malala needs to reclaim control over her mental health—breathing exercises, grounding techniques, and emotional validation. More than a therapist, she becomes a symbolic figure of healing, teaching Malala that vulnerability is not weakness but courage.

Through Evelyn, Malala learns to face her anxiety without shame, marking a crucial step in her journey toward inner peace.

Themes

Identity and Self-Discovery

In Finding My Way, the journey toward self-understanding forms the emotional backbone of Malala Yousafzai’s story. The narrative moves beyond her identity as a global icon to reveal her personal search for authenticity and belonging.

After surviving an event that catapulted her into international fame, Malala struggles to reconcile the public image of an unshakable activist with her private desire to be an ordinary young woman. This tension follows her through her education in England, where she navigates two worlds: the expectations of a Nobel laureate and the insecurities of a teenager seeking acceptance.

The early sections highlight her discomfort with constant attention, showing how fame becomes a prison that isolates her from peers. Yet this struggle also becomes the foundation for her self-awareness.

At Oxford, she begins to reclaim control over her identity—not as a symbol created by others but as a person learning, laughing, and making mistakes. Her clothing choices, friendships, and even romantic experiences serve as acts of self-definition, challenging both cultural and societal constraints.

By the book’s end, Malala’s sense of identity matures into a confident synthesis of her heritage, faith, and independence. She learns that being true to herself does not require rejecting her past but embracing it on her own terms.

Her growth is not about becoming someone new but about learning to inhabit every version of herself—student, activist, woman, and survivor—with integrity and grace.

Freedom and Control

Freedom in Finding My Way exists as both a privilege and a burden. Malala’s entire life revolves around the pursuit of freedom—first the right to learn, later the right to live without being defined by trauma or politics.

Yet true freedom proves elusive. After the attack, her physical liberation from danger coincides with a new confinement under global scrutiny.

Cameras, bodyguards, and expectations create invisible walls around her, turning even ordinary choices—such as wearing jeans—into public controversies. Her move to Oxford symbolizes a reclamation of personal liberty.

The university environment allows her to explore independence, make friends, and experience moments of rebellion that her childhood never permitted. However, these glimpses of autonomy come with backlash from conservative voices in Pakistan and tension within her family.

The conflict between external judgment and internal freedom exposes how control persists in new forms even after escaping oppression. The book also explores emotional freedom—her ability to love, to express vulnerability, and to confront mental health challenges without shame.

Therapy becomes a vital space where she learns to free herself from trauma’s grip. In the end, Malala discovers that freedom is not the absence of constraint but the power to define herself in spite of it.

Her choice to live boldly, marry on her own terms, and continue her advocacy work reflects a mature understanding that control and freedom can coexist when rooted in self-acceptance.

Resilience and Healing

Resilience shapes every aspect of Finding My Way, but its portrayal transcends mere survival. Malala’s recovery from physical injury is only the beginning; the deeper challenge lies in healing from emotional scars and reclaiming joy.

The narrative follows her evolving understanding of what it means to be strong. Early in her journey, resilience is synonymous with endurance—the ability to continue studying, working, and speaking even under pressure.

But as she matures, she realizes that strength also involves acknowledging pain and seeking help. Her therapy sessions mark a turning point where resilience becomes an act of compassion toward herself.

The exploration of PTSD, panic attacks, and anxiety gives depth to her public persona, showing that courage includes vulnerability. The love she receives from friends and family, and later from Asser, becomes another form of healing—proof that connection can mend what violence once tried to destroy.

Resilience in her story also operates on a collective level. Her advocacy for Afghan girls and her return to Pakistan reflect a shared strength rooted in solidarity and memory.

By confronting trauma, not denying it, she redefines resilience as an ongoing process rather than a final triumph. Her eventual peace comes from integrating her pain into purpose, allowing her to move forward with empathy and balance.

Gender, Culture, and Autonomy

The question of gender and cultural identity runs throughout Finding My Way, shaping Malala’s internal and external battles. Raised in a society that polices women’s choices, she grows up understanding that autonomy must be fought for at every level—from attending school to choosing what to wear.

Even after moving to England, these expectations follow her through family and social pressures. Her mother’s insistence on traditional clothing and her community’s judgment over jeans symbolize the lingering grip of patriarchal norms.

Yet Malala’s resistance is neither defiant nor dismissive; it is grounded in an effort to harmonize respect for her culture with her belief in equality. Her relationship with Asser further complicates this theme, exposing the tensions between love, independence, and societal approval.

Through these experiences, Malala examines how womanhood is shaped by both cultural inheritance and personal agency. Her refusal to apologize for her Vogue interview or conform to prescribed gender roles highlights her determination to define her life beyond binary expectations.

By the end of the book, her marriage becomes an act of equality rather than submission—a partnership rooted in respect and shared values. Malala’s journey reclaims autonomy not just for herself but as a statement for women everywhere: that faith, culture, and feminism need not be opposing forces but can coexist in harmony when chosen freely.

Belonging and Exile

Belonging forms one of the most poignant emotional currents in Finding My Way. The experience of exile—both physical and emotional—permeates Malala’s life after her forced departure from Pakistan.

Disconnected from her homeland, she grapples with an enduring sense of displacement, yearning for the familiarity of the Swat Valley even as she thrives abroad. Her reflections on home are haunted by nostalgia and guilt, intensified by online hatred and conspiracy theories that paint her as a traitor.

This estrangement deepens her loneliness, but also propels her toward a new understanding of belonging. At Oxford, friendship becomes her substitute for home—a circle of women who anchor her during times of uncertainty.

Yet her eventual return to Pakistan transforms the idea of belonging from nostalgia into acceptance. Standing in her childhood home, she recognizes that places change, but connection endures through memory and purpose.

The school she builds in Shangla stands as a living expression of her reconciliation with her roots—a bridge between who she was and who she has become. By the end, belonging is no longer tied to geography or public approval; it resides within her capacity to love, to serve, and to remember.

Through this realization, Malala affirms that exile may fragment one’s sense of identity, but it cannot erase the ties that bind the heart to its origins.