Five Bad Deeds Summary, Characters and Themes

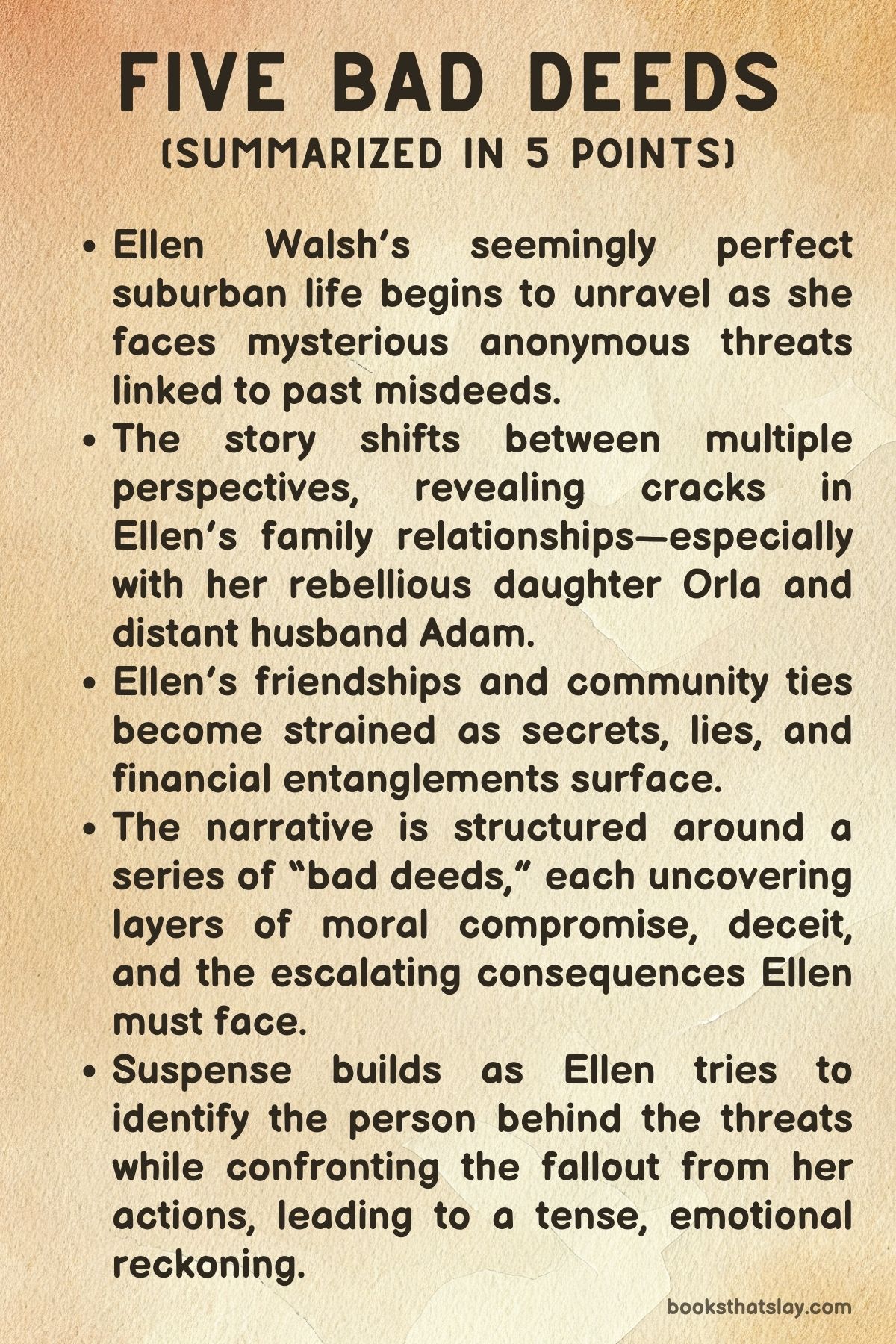

Five Bad Deeds by Caz Frear is a dark, character-driven psychological thriller set in the seemingly placid English suburb of Thames Lawley.

The novel dives beneath the carefully managed exterior of Ellen Walsh—a devoted wife, mother, and friend—revealing a maze of secrets, betrayals, and mounting paranoia. When Ellen begins receiving anonymous, menacing letters alluding to her past misdeeds, the boundaries of her orderly world crumble. Through shifting perspectives and a series of tense revelations, the novel explores the price of maintaining the “perfect” life, the corrosive power of guilt, and how the past inevitably claws its way to the surface.

Summary

Ellen Walsh has always done what’s expected.

To the world, she’s a model mother, the backbone of her family, and a respected member of her affluent Thames Lawley community.

She and her husband Adam, a lawyer often away for work, have a daughter, Orla, who’s teetering on the edge of teenage rebellion.

Their twin boys, Max and Kian, bring boisterous energy that constantly tests Ellen’s patience.

Ellen’s existence, though exhausting, feels secure—until a chilling letter arrives, upending everything she thought she controlled.

The letter’s message is clear: someone knows about Ellen’s “bad deeds,” and they plan to expose her.

The warning triggers Ellen’s deepest fears.

Paranoia mounts as more messages arrive, each referencing a specific past action and each more invasive than the last.

Ellen, who’s long considered herself above reproach, is forced to reflect on the choices she’s made to get where she is.

The story unfolds through multiple viewpoints—Ellen’s, but also Orla’s, Adam’s, and those of friends and neighbors like Gwen, Nush, Kristy, and Jason.

Each character brings their own secrets, perspectives, and judgments, highlighting the intricate social web of their community.

Ellen’s estranged sister, Kristy, has returned from a self-imposed exile, haunted and secretive, adding to Ellen’s anxiety.

Orla, struggling to find her identity, feels increasingly alienated from her mother’s relentless need for control.

As the letters escalate, so do Ellen’s suspicions.

Could Gwen, her once-best friend, be behind them?

Gwen’s demeanor has shifted, their friendship now brittle and loaded with passive-aggression.

Or is it Nush, whose resentment over a past incident lingers beneath polite smiles?

Jason, the local police officer and Gwen’s brother, also emerges as a wildcard, especially after a humiliating public incident involving Ellen and a breathalyzer.

Interspersed with these escalating present-day tensions are flashbacks and narrative interludes labeled by Ellen’s “bad deeds.”

These are moments where she manipulated, lied, or outright harmed those around her.

The first involves betraying a friend by passing on a harmful message.

The second unearths financial duplicity—a desperate act she justified as protecting her family.

Each new section peels back another layer, making clear that Ellen’s quest for perfection has come at a significant moral cost.

At home, the strain shows.

Adam withdraws, using work as both shield and escape.

Orla’s behavior grows more volatile; her mother’s suffocating grip drives her to riskier choices and emotional distance.

Kristy, fragile and volatile, threatens to unearth long-buried family secrets.

As the web tightens, Ellen finds herself isolated, her allies slipping away, her ability to manage the crisis crumbling.

Through each perspective, the reader glimpses how Ellen’s actions have shaped the people around her.

They, in turn, carry their own regrets and resentments.

The Meadowhouse, Ellen’s prized home, becomes a symbol—a beautiful façade hiding rot, built on choices that can no longer be ignored.

With each deed revealed, the anonymous tormentor’s motivations come into sharper focus, escalating Ellen’s dread.

She becomes obsessed with uncovering their identity, her thoughts spiraling with paranoia as her relationships fracture.

The book deftly maintains suspense, exploring the corrosive effects of guilt, the complexity of female friendships, and the dangers of self-deception.

As the reckoning approaches, Ellen is forced to confront uncomfortable truths about herself, her family, and the cost of her so-called “perfect” life.

This sets the stage for a devastating confrontation where no secret can remain buried.

Characters

Ellen Walsh

Ellen Walsh stands at the center of the novel as both protagonist and unreliable narrator. She is presented outwardly as the model suburban wife and mother, but her inner life is a tangle of anxieties, resentments, and unresolved guilt.

As the anonymous threats begin to infiltrate her life, Ellen’s facade slowly unravels. This reveals a person who is deeply insecure, often judgmental, and capable of self-deception.

Her relationships are fraught with manipulation and passive aggression, particularly with her husband Adam and her daughter Orla. Ellen’s past “bad deeds,” ranging from dishonesty to outright betrayal, stem from a complex mix of fear, entitlement, and a desperate need to protect her image.

She justifies her actions as survival tactics, yet the narrative exposes how these choices have isolated her from genuine intimacy. By the novel’s end, Ellen is forced to reckon not just with the consequences of her actions, but with the reality of her own character.

Orla Walsh

Orla, Ellen’s teenage daughter, embodies the turbulence and vulnerability of adolescence. She lives within a home shadowed by secrets and emotional neglect.

Orla feels misunderstood and often dismissed by her mother, which leads to a widening gulf between them. Her behavior—rebellious, secretive, and sometimes self-destructive—is both a cry for independence and a reaction to her environment.

Throughout the book, Orla’s perspective serves as a counterpoint to Ellen’s. It reveals the pain and confusion of growing up under the weight of adult mistakes and half-truths.

Her interactions, including a flirtation with an older barman, are attempts to find validation and control where she feels none. Ultimately, Orla’s arc is one of seeking truth and authenticity, as she tries to disentangle herself from her mother’s web of secrets.

Adam Walsh

Adam, Ellen’s husband, is portrayed as emotionally distant and preoccupied. He is more engaged with work and external validation than with his family.

His detachment is both a comfort and a frustration for Ellen. He allows her autonomy but also leaves her feeling unsupported and invisible.

Adam’s own moral ambiguities are hinted at but rarely explored in depth. His relationship with Ellen appears to be built more on shared history and convenience than on genuine partnership.

As Ellen’s secrets begin to surface, Adam’s role shifts from passive observer to a man forced to confront uncomfortable realities. His responses, marked by disbelief and resignation, mirror the broader theme of denial in the Walsh household.

Kristy

Kristy, Ellen’s younger sister, arrives with her own emotional wounds and a history in Ibiza that has clearly left scars. The black eye she sports and her cagey explanations signal that she, too, is running from something.

Kristy’s relationship with Ellen is complicated by childhood resentments and adult disappointments. She serves as both a reminder of Ellen’s responsibilities and a judge of her failures.

Kristy’s struggles with addiction, self-worth, and her own “bad deeds” make her both a mirror and a foil to Ellen. She is less concerned with appearances and more openly self-destructive, which brings both conflict and a strange kind of honesty to their interactions.

Nush

Nush, one of Ellen’s friends, is both confidante and eventual adversary. Their friendship, while initially supportive, is exposed as transactional and filled with unspoken competition.

Nush’s own struggles, especially with money and self-esteem, are exacerbated by Ellen’s manipulations and half-truths. When Ellen’s misdeeds begin to directly affect Nush’s life, the friendship fractures.

This highlights the fragility and superficiality of Ellen’s social bonds. Nush represents both the dangers and the inevitability of secrets coming to light, serving as a catalyst for Ellen’s unraveling.

Gwen

Gwen, another friend in Ellen’s suburban circle, initially appears supportive. However, she is gradually revealed to be harboring her own suspicions and grievances.

Her loyalty is conditional, and as the anonymous threats escalate, Gwen’s attitude shifts from empathy to distance. Beneath her smiles lie judgments and a readiness to protect herself.

Gwen’s eventual withdrawal underscores the theme of isolation. It also demonstrates the collapse of carefully constructed social facades.

Jason

Jason, Gwen’s brother and a local police officer, begins as a peripheral figure but grows in importance as Ellen’s life unravels. His authority—both as a policeman and as someone connected to the group—positions him to observe and judge the chaos.

Jason’s interactions with Ellen are layered with both official duty and personal history. This creates tension and uncertainty throughout the narrative.

As Ellen’s misdeeds come to light, Jason becomes both a potential protector and a threat. His presence underscores Ellen’s increasing sense of paranoia and the precariousness of her situation.

The Messenger

The anonymous sender of the threatening notes, eventually revealed as someone intimately familiar with Ellen’s past, acts as both antagonist and avenger. This character’s actions drive the plot and force Ellen to confront the impact of her past deeds.

The reveal is both shocking and inevitable, tying together the various strands of betrayal and hurt. The Messenger’s motivations stem from genuine pain and a desire for justice.

This makes them a complex figure, rather than a simple villain. Their presence is a constant reminder of the story’s central question: whether anyone can truly escape the consequences of their actions.

Themes

The Disintegration of the Suburban Ideal: How the Pursuit of Perfection Conceals Rot and Breeds Destruction

At the center of Five Bad Deeds lies a ruthless examination of the suburban dream—a meticulously constructed façade that promises safety, harmony, and self-fulfillment. Ellen’s life in Thames Lawley, surrounded by manicured lawns, competitive mothers, and the aspiration for domestic bliss, initially appears enviable.

Yet, as the narrative peels back the layers, it exposes the rot festering beneath the surface: marital estrangement, fraught parent-child relationships, and corrosive secrets. The Meadowhouse itself becomes emblematic—a coveted trophy whose very acquisition is mired in deceit and manipulation.

As Ellen’s grip on her family and social standing slips, the illusion of the idyllic suburb unravels, revealing the psychological toll of living for appearances. Five Bad Deeds suggests that the relentless pursuit of perfection does not just mask imperfection—it actually breeds it, as individuals compromise their morals, fracture their relationships, and make increasingly desperate choices to maintain the lie.

In this way, the novel indicts the myth of suburban invulnerability and exposes how conformity and material ambition can serve as incubators for alienation, anxiety, and moral failure.

The Banquet of Consequences

A central, haunting motif in the novel is the idea that “sooner or later, everyone sits down to a banquet of consequences.” This theme extends far beyond simple comeuppance; it interrogates the ways in which guilt accumulates, festers, and ultimately demands payment, often in forms both expected and unforeseen.

Each of Ellen’s “bad deeds” initiates a ripple effect, implicating not just herself but her family, friends, and wider community. The narrative structure—divided into discrete acts of wrongdoing—mimics the relentless, recursive nature of guilt and retribution.

The anonymous threats and the incremental unveiling of Ellen’s past betrayals heighten the sense of inevitability: there is no erasing, only postponing, the moment of reckoning. Even as Ellen rationalizes or attempts to contain the fallout, the consequences of her actions prove inescapable, manifesting as both external judgment and internal torment.

In the end, the most punishing sentence is not legal or social sanction, but the corrosive self-awareness of one’s own moral decay. The novel thus explores the existential weight of responsibility—how even the smallest betrayals, left unacknowledged, will eventually demand to be reckoned with.

Surveillance, Paranoia, and the Erosion of Trust in Intimate Communities

Five Bad Deeds thrives on a pervasive atmosphere of surveillance and suspicion, highlighting the dangers of living within tightly-knit, ostensibly supportive communities. Ellen’s paranoia is stoked not just by the threatening letters but by the constant scrutiny of neighbors, friends, and even family members.

Thames Lawley is depicted as a panopticon, where everyone is both observer and observed, and social capital is weaponized through gossip, judgment, and passive aggression. As the narrative shifts through various perspectives, the reader witnesses how quickly trust can curdle into suspicion—how the very intimacy that holds a community together can become a vector for betrayal.

The “messenger’s” campaign of psychological terror amplifies these dynamics, exposing the fragility of social bonds built on secrecy and performance.

In Frear’s vision, the dangers of being known are as acute as the dangers of being alone; the gaze of others is both a source of validation and a tool of punishment, and ultimately, no secret can withstand the relentless pressure of collective surveillance.

The Fragmentation of Identity Under Pressure

One of the novel’s most challenging and poignant themes is the way in which Ellen’s sense of self fractures under the relentless pressures of motherhood, marriage, and societal expectation. Ellen is constantly negotiating conflicting roles—nurturing mother, dutiful wife, loyal sister, trustworthy friend—and finds herself failing in all of them as the crisis deepens.

The novel refuses to present Ellen as a simple villain; rather, it interrogates the impossibility of living up to competing, often contradictory demands. The narrative’s shifting points of view, particularly from the perspectives of Orla, Kristy, and the other women in Ellen’s orbit, highlight the different ways women internalize guilt, competition, and resentment.

The unraveling of Ellen’s identity becomes both a personal tragedy and a commentary on the structural forces that set women up to fail: the pressure to “have it all,” the demand for self-sacrifice, the fear of judgment, and the shame of imperfection. As her world collapses, Ellen’s journey is not just about the exposure of her secrets, but about the existential disintegration—and possible reassembly—of her selfhood.

The Weaponization of Intimacy

Five Bad Deeds masterfully explores the dark potential of intimacy—the ways in which those closest to us have both the knowledge and the motive to hurt us most deeply. Ellen’s relationships with Kristy, Nush, Gwen, Adam, and Orla are shaped not only by love, but by complex undercurrents of jealousy, competition, unresolved trauma, and mutual dependence.

As Ellen’s secrets are revealed, the people she once relied upon for support become agents of her undoing, willingly or otherwise. The identity of the “messenger” is a devastating twist precisely because it emerges from within her inner circle, underscoring the theme that our greatest vulnerabilities are known not to strangers, but to those we let closest.

In the world of the novel, intimacy is a double-edged sword: it is the source of connection, but also the arena where power is asserted, grievances are tallied, and retribution is enacted.

The ultimate tragedy, then, is not just Ellen’s loss of reputation or stability, but the irrevocable shattering of trust and love in the spaces where she once felt most secure.