Floreana by Midge Raymond Summary, Characters and Themes

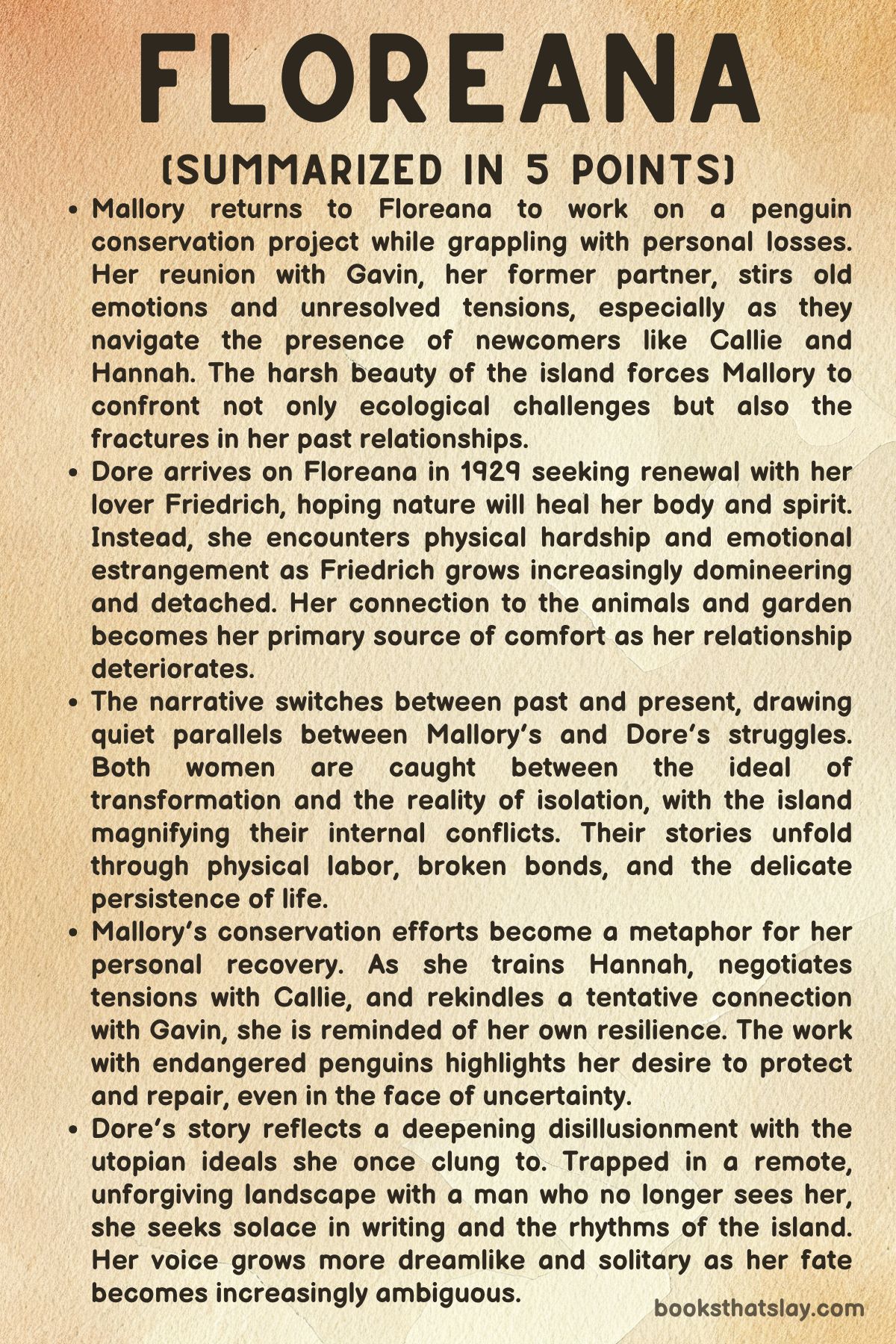

Floreana by Midge Raymond is a deeply immersive dual narrative that captures the haunting echoes between two women separated by a century but united by place and personal struggle. Set on the remote Galápagos island of Floreana, the story juxtaposes Mallory, a modern-day scientist grieving her daughter and unraveling her own fractured identity, with Dore Strauch, a 1920s German settler whose life becomes entwined with a utopian dream gone wrong.

Through journal entries, fieldwork, and emotional reckonings, the novel explores how isolation, nature, and memory shape who we are—and who we may yet become—under extreme emotional and environmental pressure.

Summary

In Floreana, Midge Raymond presents two parallel yet intricately resonant narratives centered on the island of Floreana in the Galápagos. The novel shifts between Mallory, a present-day scientist returning to the island after personal and professional upheaval, and Dore Strauch, a German woman who fled to the island nearly a century earlier seeking freedom and renewal.

Through alternating voices and temporal layers, the story explores identity, grief, disillusionment, and the complicated bond between humans and the natural world.

Mallory returns to Floreana after ten years to rejoin a penguin conservation project she once helped build. Her past on the island is tangled with Gavin, a former mentor and romantic partner whose cool demeanor on her return hints at unresolved pain.

Mallory’s decision to leave a decade earlier was driven by a desire for stability, motherhood, and conventional life. Now, estranged from her husband Scott and haunted by the accidental death of her daughter Emily—who died after consuming a peanut-contaminated cookie—Mallory is seeking refuge in the very place she once abandoned.

Her reintroduction to the project, which involves constructing artificial nests for endangered Galápagos penguins, is marked by emotional tension and physical strain. Gavin, still invested in the cause but emotionally distant, has replaced her with Hannah, a young assistant whose family contributes funding.

Mallory’s return is met with cautious accommodation rather than welcome. As she labors in the harsh terrain, carrying lava stones and hollowing out nests, she wrestles with memories of her early passion for science, the thrill of discovery with Gavin, and the series of choices that led her to a life that ultimately broke apart.

Dore’s narrative unfolds through secret journals discovered by Mallory in a cave. Dore arrived on Floreana in 1929, fleeing a repressive marriage and following her lover, Friedrich, in hopes of building a utopian existence.

But the island is less paradise than crucible. Dore’s physical ailments—rheumatism and digestive issues—are exacerbated by Friedrich’s asceticism and emotional detachment.

Once enamored by his philosophical convictions, she now finds them increasingly rigid and punishing. Friedrich refuses basic comforts and demands that their lives adhere strictly to his ideals, even when it causes her suffering.

As Mallory begins translating the journals with Diego, a local translator who becomes her confidant and lover, she grows more entangled in Dore’s past. Through long nights on the beach, she reads Dore’s words aloud and reflects on the eerie similarities between their lives—both women shaped by love that curdled into control, both seeking clarity in isolation, and both forced to confront their own complicity in painful outcomes.

Dore’s journal reveals a slow unraveling of her life with Friedrich. Her emotional solitude becomes profound, especially after a series of miscarriages.

In a desperate effort to find solace, she names animals—her cat, donkey, and chickens—after the children she will never have. These animals become her emotional lifeline.

The arrival of the flamboyant and manipulative Baroness and her entourage further disrupts the island’s already fragile social order. The Baroness steals food, brandishes weapons, and uses sex and spectacle to control those around her.

Dore, drawn to the Baroness’s lover Rudy, finds in him a gentleness she has longed for. Their brief physical connection is more emotional than erotic—a moment of reprieve in a world that has offered little compassion.

Back in the present, Mallory’s emotional journey intensifies. She feels alienated from Gavin and struggles with the implications of her growing relationship with Diego, especially after she discovers he has sold Dore’s journals to a filmmaker named Callie.

Furious and betrayed, Mallory confronts Diego and Callie, only to be caught in a dangerous moment when Callie is stung by a stingray. In the panic that follows, Diego saves Callie’s life and later redeems himself by returning the journals to Mallory.

This act softens Mallory’s heart and renews their connection, though the trust between them remains fragile.

Meanwhile, Mallory’s bond with Dore deepens. The journals reveal that Dore eventually poisons Friedrich in an act of desperation but later reverses her decision, saving him and choosing to live.

She escapes the island on a yacht, possibly pregnant with Rudy’s child. This revelation leads Mallory to believe that she herself may be descended from Dore, through Dore’s daughter Johanna.

This potential genealogical connection transforms Mallory’s understanding of her place on the island—not merely as a scientist or visitor, but as someone whose roots may reach back through time to the very story she’s been uncovering.

This recognition reframes Mallory’s entire experience. She donates the journals to Gavin, both as an offering of peace and as a gesture toward legacy and understanding.

The contribution benefits the penguin conservation project, symbolically mending the rupture between their past and present selves. Their renewed alliance is quiet and cautious, but meaningful.

Together, they aim to restore not just nests for birds, but a sense of shared purpose.

Mallory begins to see that healing comes not from escape, but from integration—from accepting the messy coexistence of past and present, loss and survival. She reaches out to Scott, opening a door that had long been closed, and agrees to return to Floreana for another research season.

The decision is not about fleeing grief but about embracing the complexity of who she is: mother, scientist, partner, and descendant of women who also tried, failed, and tried again.

Floreana closes with Mallory standing not at a point of conclusion, but at a threshold. The island, once a symbol of disappointment and hardship, becomes a site of personal reckoning and possible redemption.

As she steps into her future, the echo of Dore’s past lingers—not as a ghost, but as a guide. Their stories, bound by landscape and longing, affirm the resilience of women who seek not just to survive, but to understand and reclaim their own voices.

Characters

Mallory

Mallory is the emotional and thematic anchor of Floreana, embodying the modern tension between personal ambition, motherhood, and grief. A field researcher who once found joy in ecological work, she returns to Floreana to participate in a conservation project involving endangered Galápagos penguins.

Her arrival, however, is not only professional—it’s deeply personal. Haunted by the death of her daughter Emily, whose severe peanut allergy led to a fatal oversight during a sleepover, Mallory carries immense guilt.

This grief has fractured her marriage to Scott and left her emotionally adrift. Her identity is in flux; she is no longer the daring scientist who swam with penguins nor the vigilant mother who tried to protect Emily from the world.

Her time on the island becomes a journey of reconciliation between these fragmented selves. The physical labor of creating artificial nests mirrors her internal efforts to rebuild her identity.

Through her interactions with Diego and Gavin, two men who represent different facets of her emotional history, Mallory is forced to examine not only her romantic past but also her future possibilities. Her discovery of Dore’s journals becomes transformative, allowing her to process her own pain through another woman’s forgotten voice.

The eventual realization that she might be Dore’s descendant solidifies her emotional investment in the island and its history, giving her a sense of continuity and belonging. Mallory’s arc is one of layered healing—not a return to who she was, but an embrace of who she is becoming.

Dore Strauch

Dore is a haunting, fiercely human presence in Floreana, offering a raw and intimate account of early twentieth-century life on the island. Fleeing a repressive life in Berlin, she arrives on Floreana with Friedrich, her lover, in search of a utopian rebirth.

Yet her dream of spiritual and romantic freedom quickly deteriorates. Floreana, with its brutal terrain and harsh isolation, becomes the crucible that reveals Friedrich’s controlling nature and emotional detachment.

His Nietzschean worldview, once intellectually alluring, proves devastating in practice—devoid of tenderness, riddled with rigidity, and ultimately oppressive. Dore’s physical ailments and emotional vulnerabilities are treated with dismissiveness, and her existence is reduced to a subordinate role in Friedrich’s grandiose ideals.

However, she resists erasure in quiet but potent ways: tending to her animals, planting flowers, and maintaining her vegetarianism despite hunger. These acts become forms of autonomy and spiritual rebellion.

Her journals chronicle a descent into despair, catalyzed by the violent arrival of the Baroness and the complexities of her attraction to Rudy. Her complicity in the disposal of the Baroness’s body and eventual poisoning of Friedrich reflect a profound moral and emotional unravelling.

Yet Dore survives, escaping Floreana after saving herself from the consequences of her own actions. Her writings—kept secret from the public version of her story—offer a brutally honest window into the cost of idealism, the hunger for love, and the endurance of the feminine spirit against psychological and environmental brutality.

Gavin

Gavin serves as a mirror to Mallory’s past and a representation of the professional and personal world she left behind. A conservationist devoted to Floreana’s penguin population, Gavin is stoic, methodical, and emotionally guarded.

Once Mallory’s mentor and lover, his initial coldness upon her return reflects the unresolved tension and betrayal he still harbors. Their past relationship had been rooted in shared passion—for science, for each other, and for the island—but Mallory’s decision to leave him for a more conventional life left a wound that has not healed.

Despite his outward detachment, Gavin remains committed to the mission, even when faced with the bureaucratic compromises that come with funding, such as accepting Hannah’s participation due to her family’s donations. His willingness to take the journals for preservation at the end of the story suggests a reconciliation, not necessarily romantic, but one rooted in mutual respect and a shared purpose.

Gavin is a figure of steadiness and principle, embodying the continuity of the island’s scientific legacy even as personal histories shift around him.

Friedrich

Friedrich represents the darker edge of idealism in Floreana—a man whose philosophical convictions obliterate empathy and human connection. Initially portrayed as Dore’s intellectual partner, he soon emerges as a cold and authoritarian figure.

His rigid adherence to Nietzschean principles strips their life of compassion and comfort, framing survival and suffering as necessary virtues. His refusal to share a bed, his rejection of sweetness in food and life, and his emotional unavailability reveal a deeply self-absorbed worldview.

While Dore longs for partnership and understanding, Friedrich reduces her to a tool in his philosophical experiment. His transformation from charismatic thinker to tyrannical survivor mirrors the island’s effect on human aspirations—it lays bare the inadequacies of ideology when confronted with lived experience.

Friedrich’s ultimate fate—being poisoned by Dore, then nursed back to health—highlights both his vulnerability and the fraying power dynamics in their relationship. He is both victim and villain, a tragic figure of intellectual hubris undone by his refusal to see others as whole beings.

Diego

Diego is a symbol of possibility and moral ambiguity in Mallory’s story. A local translator who aids Mallory with Dore’s journals, he becomes both a romantic interest and a point of ethical tension.

Their initial connection is grounded in shared curiosity and empathy, particularly in scenes where Diego helps Mallory with tasks like relocating the predatory cat threatening penguins. His emotional sensitivity provides a foil to Gavin’s aloofness, and their growing intimacy offers Mallory a brief reprieve from grief.

However, Diego’s betrayal—selling the journals to Callie—reveals his own vulnerability to temptation and pressure. His eventual return of the journals, particularly after the chaos of the stingray incident, is a quiet redemption arc.

He embodies the complexities of trust and the fragility of connection in isolated settings. Diego is not just a love interest but a conduit for Mallory’s transformation—his imperfections forcing her to confront not only others’ betrayals but her own capacity for forgiveness and growth.

Rudy Lorenz

Rudy is a fleeting but pivotal figure in Dore’s life, representing the emotional intimacy she desperately seeks. As one of the Baroness’s lovers, Rudy’s presence on the island introduces chaos but also the potential for tenderness.

Dore is drawn to him not only because of his physical presence but because of the humanity and gentleness he exhibits in contrast to Friedrich. Their brief kiss becomes a moment of defiance for Dore, a gesture toward reclaiming her own desire and agency.

Yet Rudy’s loyalty to the Baroness, and later his tragic demise, underscores the futility of these brief connections in such a merciless setting. Rudy’s role, though limited in duration, is emotionally significant—he is both a symbol of what could have been and a casualty of the island’s corrosive environment.

The Baroness

The Baroness is a force of disruption and manipulation in Dore’s narrative, embodying the colonial fantasy of domination dressed in theatrical flair. Her arrival shatters the fragile equilibrium of Floreana, injecting volatility into the already tense atmosphere.

Armed, dramatic, and ruthlessly self-serving, she seizes resources, intimidates fellow settlers, and blurs the lines between performance and power. She is a provocateur whose presence exposes the simmering resentments and hypocrisies of the island’s inhabitants.

Yet even in her cruelty, the Baroness is a fascinating figure—someone who dares to live outside societal norms, even if at others’ expense. Her mysterious death and the subsequent disposal of her body by Dore and Rudy serve as a climax of the narrative’s moral ambiguity.

The Baroness’s life and demise encapsulate the dangerous allure of charisma unmoored from empathy.

Callie

Callie is a minor but impactful character in the present-day storyline, representing the modern commodification of history and trauma. A filmmaker interested in Dore’s story, Callie is willing to manipulate and exploit others to achieve her goals.

Her involvement with Diego and the journals brings her into direct conflict with Mallory, culminating in the stingray incident—a moment that borders on life-threatening chaos. Callie’s character is less about depth and more about function: she is a foil to Mallory’s evolving integrity, a reminder that not all quests for truth are rooted in respect or responsibility.

She embodies opportunism in contrast to the more reflective arcs of Mallory and Dore.

Emily

Though deceased, Emily casts a long emotional shadow over Floreana. Her presence is felt through Mallory’s memories, regrets, and dreams.

Emily represents both innocence and the unbearable weight of parental guilt. Her death due to a preventable allergy incident becomes the crucible of Mallory’s psychological collapse and transformation.

She appears in dreams and recollections not just as a lost child but as a symbol of Mallory’s lost self. The bedtime story about mermaids and sea turtles, shared with Emily, becomes a meta-narrative that reflects Mallory’s inner longings and her eventual journey toward healing.

Emily’s role is ghostly yet profound, shaping every choice Mallory makes on the island.

Scott

Scott, Mallory’s estranged husband, exists primarily in the background of Floreana, yet his absence is as resonant as any character’s presence. His failure to prevent Emily’s death and the dissolution of his marriage with Mallory reflect the crushing weight of shared trauma.

Scott symbolizes the emotional chasm that can emerge when grief is handled in isolation rather than partnership. Mallory’s eventual decision to reach out to him suggests a willingness to rebuild or at least find peace.

While he is never physically present on Floreana, Scott remains integral to Mallory’s emotional landscape, serving as both a reminder of what was lost and a question mark over what might be reclaimed.

Themes

Reinvention and the Illusion of Escape

Both Mallory and Dore arrive on Floreana with the conviction that a new location can offer a new self. This desire to escape—from professional burnout, familial estrangement, or oppressive relationships—initially carries the allure of freedom and control.

However, the island’s harsh conditions and emotional isolation reveal the fallacy in believing that reinvention is a clean break from the past. For Mallory, the physical act of returning to Floreana under the guise of scientific purpose brings her face to face with unresolved personal wounds, including the loss of her daughter and the collapse of her marriage.

Similarly, Dore’s romanticized vision of island life with Friedrich is quickly dismantled by the unrelenting physical hardships and emotional neglect she endures. In both narratives, the island does not grant rebirth through erasure, but instead forces a confrontation with what was left behind.

The attempt to start anew is portrayed not as a leap into freedom but as a grueling negotiation with memory, expectation, and consequence. Reinvention, the novel suggests, must be rooted in integration rather than abandonment—an acknowledgment that no matter how remote the destination, one’s inner struggles cannot be left at the shoreline.

Female Agency and Emotional Repression

Dore and Mallory both experience relationships that initially seem collaborative or supportive but gradually expose power imbalances. Friedrich’s philosophical rigidity and Gavin’s professional detachment mask emotional indifference that undermines the women’s sense of self-worth and voice.

For Dore, this imbalance manifests in her diminished agency within her partnership, as Friedrich’s intellectual ideals consistently override her physical and emotional needs. His coldness and refusal to compromise push her into silence, except in her private journal entries, which become the only space where her truth exists.

Similarly, Mallory’s relationship with Gavin, once a partnership of scientific curiosity and romantic promise, devolves into a space of emotional unavailability and suppressed desire. Both women begin to reclaim their agency not through dramatic rebellion but through quieter, internal acts—Dore through nurturing animals and writing, Mallory through acknowledging her grief and allowing new intimacy with Diego.

The novel critiques the emotional repression women often endure under the guise of rationality or ambition and underscores the necessity of reclaiming voice, both literal and metaphorical, to assert autonomy in environments that seek to suppress it.

The Burden of Motherhood and Grief

The theme of motherhood in Floreana is not framed around idealized care but around its emotional weight, its impossibility, and its losses. Mallory’s identity as a mother is fractured by guilt over her daughter Emily’s death, which was rooted in a preventable but fatal oversight.

Her hypervigilance as a parent—stemming from Emily’s severe allergies—becomes a double-edged sword: while it reflects her deep care, it also alienates her from her husband and contributes to her eventual isolation. Her grief is not simply about loss, but about self-judgment, failure, and the impossibility of ever doing enough.

For Dore, the absence of children is a silent wound that echoes throughout her island life. Miscarriages and unfulfilled maternal desires lead her to project nurturing instincts onto animals, which she names after the children she lost.

These creatures become emotional surrogates, filling a void that Friedrich neither acknowledges nor shares. The narrative reveals that grief in motherhood is often invisible, socially unrecognized, and deeply internalized.

Both women live with maternal ache—one from having lost a child, the other from never having had one—and this shared experience becomes a powerful undercurrent linking their lives across generations.

Isolation as Mirror and Catalyst

Floreana is not merely a backdrop but a mirror reflecting each woman’s internal landscape. The island’s physical remoteness amplifies emotional isolation, acting as both punishment and purification.

The absence of modern comforts or social structures means that there is no external distraction from inner turmoil. For Mallory, the silence of the caves and the solitude of the terrain force her to engage with her pain, not avoid it.

Her rediscovery of Dore’s journals provides not just historical insight but a form of communion, as though the island is guiding her through its ghosts. Dore, in her own time, experiences this isolation more viscerally, with her deteriorating health and Friedrich’s emotional abandonment driving her further inward.

Yet in both cases, isolation becomes a crucible for transformation. It strips away pretense, tests resilience, and demands clarity.

The island teaches that healing does not come through escape from others, but from learning to sit with oneself, however fractured that self may be. Isolation in Floreana becomes a spiritual reckoning, where the absence of noise allows buried truths to rise and demands that the women either break or rebuild.

Legacy, Memory, and the Power of Narrative

The uncovering of Dore’s private journals acts as a counterweight to the sanitized, public version of her life that had previously circulated. This tension between public narrative and private truth speaks to the broader theme of who controls memory and legacy.

Dore’s journals contain confessions, desires, and emotional truths that were never meant to be seen, and yet they become instrumental in Mallory’s own reckoning with the past. By reading them, Mallory confronts not only Dore’s experiences but her own emotional realities.

The act of writing and reading becomes a transgenerational bridge, where hidden stories resurrect the forgotten voices of women. Dore’s decision to record her truths in secret reflects the limited spaces women are often given to express dissent or dissatisfaction.

Mallory’s decision to preserve those journals and share them with Gavin for conservation purposes becomes a redemptive gesture, one that honors truth over mythology. In this way, Floreana highlights the immense power of narrative—not just as documentation, but as a reclamation of agency and a reshaping of historical memory.

The novel insists that private stories, even if uncomfortable or inconvenient, are the ones that truly carry the soul of a life lived.