Freedom by Angela Merkel Summary and Analysis

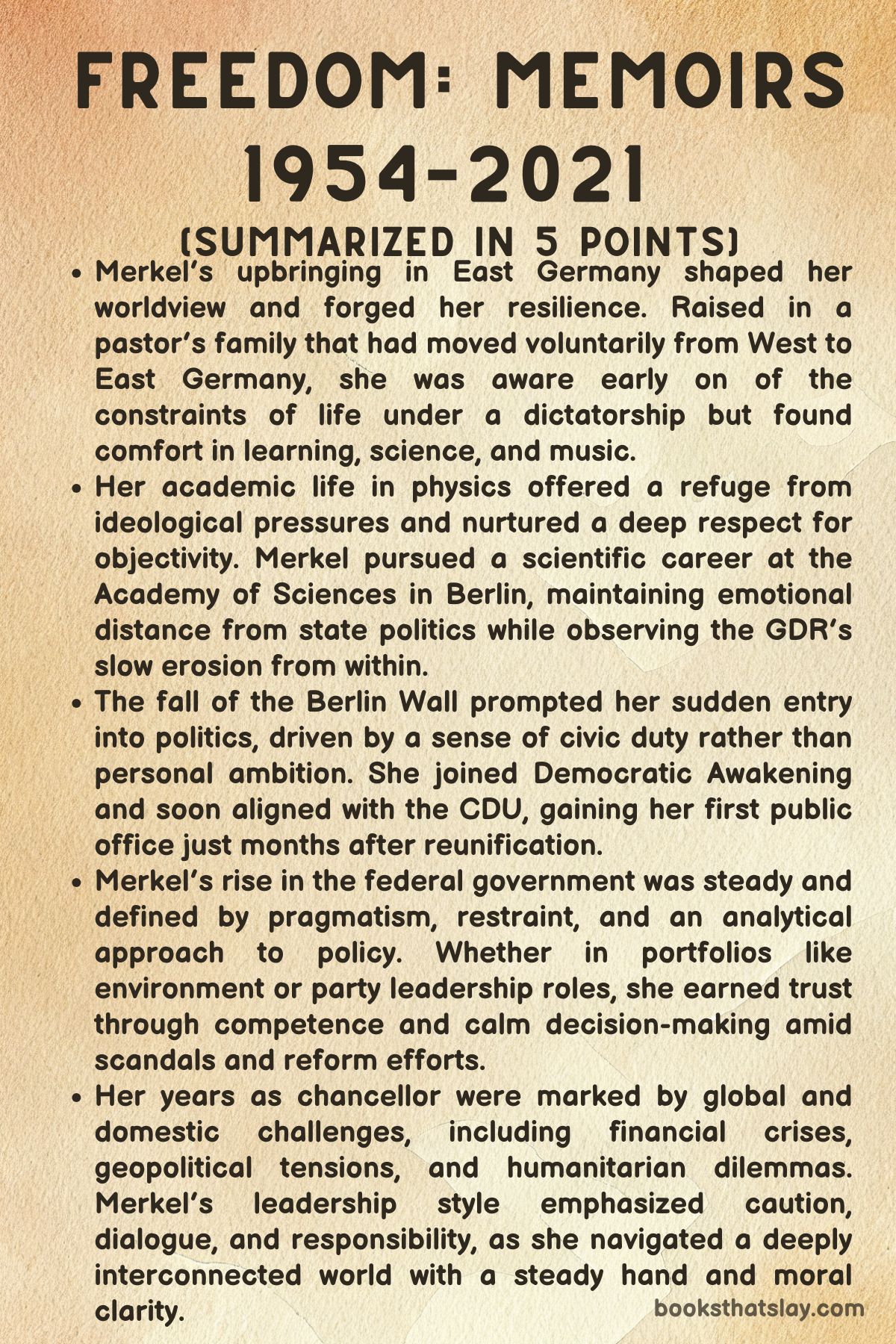

Freedom by Angela Merkel is a deeply introspective memoir chronicling the improbable journey of one of the world’s most influential political leaders. Written with her long-time adviser Beate Baumann, the book explores Merkel’s roots in East Germany, her scientific background, and her transformation into the Chancellor of a reunified Germany.

Through candid storytelling, Merkel not only reflects on her personal evolution but also engages critically with major global events during her tenure—ranging from the refugee crisis to the COVID-19 pandemic and Russia’s escalating aggression. This is more than a political memoir; it is a reflection on moral responsibility, resilience, and the fragile nature of democratic governance.

Summary

Freedom begins with Angela Merkel acknowledging the extraordinary arc of her life. Born in West Germany in 1954, her family moved to East Germany soon after her birth, drawn by her father’s pastoral calling.

From this beginning, she lived under the scrutiny and pressure of a regime that shaped every part of daily life, and she emphasizes early on that the unique trajectory of her life—from physicist in the GDR to Chancellor of a unified Germany—could not be replicated. The book opens with a reflection on her 2015 decision to allow Syrian refugees into Germany, a deeply controversial yet humane move that shaped her later years in office and prompted her to document her motives and legacy in her own voice.

The narrative then moves into her childhood in Quitzow and later Templin, depicting an upbringing shaped by rural life, a morally upright family, and the ideological controls of East Germany. She describes a close-knit household led by parents who modeled ethical responsibility.

Her father’s unwavering principles and her mother’s strength in managing the household shaped Merkel’s inner fortitude. Despite ideological pressures, their home remained a haven of intellectual freedom and emotional support.

Merkel portrays herself as a quiet observer who adapted, withheld opinions strategically, and learned how to navigate a rigid system without fully yielding to it.

She recalls her academic years and scientific pursuits in the late 1970s, particularly her work at the Central Institute for Physical Chemistry in Berlin. Life in East Germany was marked by technological scarcity, ideological conformity, and the quiet oppression of the Stasi.

Even within a state-run research institution, she found ways to engage with her colleagues and remain intellectually curious. Her work on quantum chemistry involved outdated equipment and complex bureaucracy, but she thrived in the camaraderie of informal gatherings and interdisciplinary exchanges.

Merkel also sheds light on her growing discomfort with ideological indoctrination, especially as she was required to take courses in Marxist-Leninist thought. While never openly rebellious, she began to question the regime’s constraints.

An incident involving a fellow student who criticized Soviet actions and faced harsh consequences deeply affected her. These moments solidified her belief in pragmatism over protest and in preserving her ability to think freely by staying out of overt political confrontations.

Parallel to her professional life, Merkel narrates personal experiences that further reveal the complexities of East German life. Her marriage to Ulrich and its quiet dissolution are recounted with honesty.

When she moved into a vacant apartment illegally, she again showed her tendency toward practical, low-profile defiance of the system. She managed to legalize her residency through bureaucratic maneuvering, demonstrating her skill in navigating a system built on surveillance and control.

Churches played an important role in Merkel’s personal growth. As semi-autonomous spaces, they allowed for political discourse disguised as religious discussion.

Merkel was drawn to circles of young people and intellectuals who discussed peace, environmental issues, and the constraints of East German society. These forums allowed her to test ideas and beliefs without attracting the attention of the state.

Her interactions with scientists from Poland and Czechoslovakia broadened her understanding of resistance and reform across the Eastern Bloc. Watching Poland’s Solidarność movement, and seeing the brutal suppression of reform efforts in neighboring countries, gave her a sobering perspective on the limitations of change under authoritarian rule.

Encounters with Western scientists also offered her glimpses of a freer intellectual culture. These experiences further nudged her toward a philosophy grounded in patience, persistence, and internal strength.

In 1987, Merkel was granted permission to travel to West Germany for the first time. By then, her attitude toward the GDR had hardened into quiet disillusionment.

The most striking moment comes when she recounts the fall of the Berlin Wall. She did not experience it as a revolutionary but as a citizen returning from work.

She casually joined the crowds crossing into West Berlin, treating it as a spontaneous exploration rather than a political event. This humble, almost passive engagement reflects her personality and leadership style—rational, composed, and free from dramatization.

The memoir transitions from personal recollection to global geopolitics in later chapters. Merkel reflects on the evolving relationships between the European Union, Ukraine, and Russia.

She articulates the dilemma of whether Ukraine should have been offered NATO’s Membership Action Plan, noting that such moves risked further provoking Russia. Instead, she favored closer EU alignment through programs like the European Neighborhood Policy and the Eastern Partnership.

These approaches were designed to pull Ukraine and Georgia toward European standards without direct military alliances.

However, Russia perceived any Western influence in its former sphere as a threat. This hostility erupted in Georgia in 2008 and intensified in Ukraine after the 2013 Maidan protests.

Merkel chronicles how Ukrainian ambitions toward the EU met fierce Russian resistance—culminating in the annexation of Crimea and the support for separatist movements in Eastern Ukraine. These events, she explains, fractured post-Cold War stability and pushed Europe into a more defensive posture.

Merkel played a pivotal role in diplomatic responses to the crisis, particularly the Minsk negotiations of 2015. Alongside French President Hollande, she participated in grueling talks with Ukrainian President Poroshenko and Russian President Putin.

Though agreements were signed, implementation remained elusive, and she portrays Putin as a leader determined to destabilize Ukraine to prevent its Western alignment. Merkel’s depiction of this period is marked by frustration, realism, and a sense of moral obligation to protect European peace through diplomacy, even as she confronted its limits.

Another significant portion of the memoir details her relationship with Israel and her concept of “reason of state”—Germany’s moral commitment to Jewish remembrance and the defense of Israel. Her 2008 visit to a kibbutz and her historic speech at the Knesset underscore her sincere engagement with these themes.

Merkel balanced support for Israel with critiques of policies she found troubling, particularly the settlement expansions under Netanyahu.

Toward the end of the book, she reflects on her decision to step down from political life. Embracing the Greek idea of “Kairos”—the right moment—Merkel concluded that leadership is not just about persistence but knowing when to pass the baton.

Her final years in office were consumed by the COVID-19 pandemic, which tested her scientific instincts and moral compass. She implemented unprecedented lockdowns, promoted mask-wearing and vaccination, and addressed the nation with rare, emotional televised appeals.

Her ability to blend rationality with empathy helped steer Germany through the crisis, even as political divisions deepened.

In her closing reflections, Merkel underscores the fragility of democracy, the weight of history, and the imperative of ethical leadership. Her memoir closes not with triumphalism but with a steady assertion of responsibility.

Freedom is not just a personal chronicle—it is a guide to leadership shaped by humility, discipline, and an unwavering commitment to the common good.

Key People

Angela Merkel

Angela Merkel stands as the central figure of Freedom, not only as its author but as its subject and moral compass. Her portrayal is grounded in personal vulnerability, intellectual clarity, and ethical resilience.

Raised in the GDR, Merkel’s early life in a constrained, authoritarian system instilled in her a profound sense of caution, pragmatism, and internal resistance. Her youth was shaped by the interplay of intellectual inquiry and state-imposed limitations, a tension she navigated with quiet determination rather than overt rebellion.

Merkel’s reflections on her education and early career reveal a young woman deeply committed to scientific inquiry, even as she subtly questioned the ideological premises of the state. Her resistance was never theatrical—it lay in her insistence on self-determination, her refusal to become ideologically compliant, and her tactical choice to prioritize her education and mental wellbeing over party conformity.

As a professional scientist, Merkel emerges as a disciplined, intellectually curious, and quietly rebellious individual. Her work at the Central Institute for Physical Chemistry and her candid reflections on the frustrations of GDR bureaucracy reveal a personality shaped by both humility and steely resolve.

Her early marriage, subsequent separation, and discreet independence in Berlin add emotional nuance to her character, showcasing a woman who evolved through introspection and personal accountability rather than dramatics.

Merkel’s ascent to political prominence is prefaced by a gradual ideological awakening. She presents herself as a reluctant but deeply responsible leader, whose motivations stem from a sense of duty rather than personal ambition.

Her response to the refugee crisis in 2015, her stewardship during the COVID-19 pandemic, and her approach to EU-Russian tensions reflect her deeply held belief in moral responsibility, constitutional fidelity, and diplomatic patience. Throughout the memoir, Merkel’s character is defined by her synthesis of scientific rationalism with ethical governance, her deep belief in democratic moderation, and her capacity to lead through consensus and restraint rather than charisma or populism.

Horst Kasner (Angela Merkel’s Father)

Horst Kasner, Merkel’s father, looms large in her moral and intellectual formation. A Protestant pastor who willingly moved his family from West to East Germany, Kasner embodied an unflinching moral compass.

His decision placed his family under an authoritarian regime, yet it also placed them at the intersection of faith, service, and resistance. Kasner’s principled stance on ethics, paired with a contemplative lifestyle centered around the Waldhof estate, formed the bedrock of Merkel’s internal value system.

He did not resist the GDR regime through public outcry, but through an unwavering dedication to spiritual and intellectual autonomy. Through his sermons and church-led community, Kasner modeled a kind of quiet defiance that deeply shaped Merkel’s later ability to withstand external pressure and to govern without seeking public approval.

He was, in her eyes, both a shelter and a compass—both emotionally and intellectually.

Herlind Kasner (Angela Merkel’s Mother)

Herlind Kasner, a teacher and mother, is portrayed as the emotional linchpin of Merkel’s early life. Though not “officially” employed in a regime that often defined worth by state participation, Herlind managed the family’s domestic world with integrity and grace.

She was Merkel’s first educator, introducing her daughter to the value of learning, language, and order. Herlind’s navigation of the practical difficulties of East German life—scarcity, surveillance, and social scrutiny—offered Merkel a model of emotional intelligence and perseverance.

She was both practical and intellectually oriented, reinforcing values of self-sufficiency, empathy, and resilience. Herlind’s influence is evident in Merkel’s later approach to leadership—her ability to balance empathy with practicality, and her tendency to speak sparingly yet substantively.

Ulrich Merkel

Ulrich Merkel, Angela’s first husband, represents a brief but revealing chapter in her personal journey. Their marriage, which ultimately ends in divorce, underscores the emotional and existential uncertainties that Merkel faced in her young adulthood.

The dissolution of their relationship, portrayed without bitterness or sensationalism, mirrors Merkel’s evolution from dependence to autonomy. The emotional ambivalence of their separation becomes a pivotal moment for Merkel, pushing her into a phase of self-reliance.

Squatting in a vacant apartment and managing the bureaucratic complexities of her living situation, she reasserts her independence in both symbolic and practical terms. Ulrich’s presence in the narrative serves as a counterpoint to Merkel’s development—a chapter closed with quiet dignity rather than dramatic upheaval.

“Antarctic Man”

“Antarctic Man,” a fellow student and colleague, is an anonymous but symbolic character representing the peril of dissent in East Germany. His story—a promising academic career curtailed after he spoke out against martial law in Poland—profoundly affects Merkel.

He becomes a figure of cautionary consequence, a living reminder of the risks associated with ideological noncompliance. His punishment crystallizes for Merkel the stakes of open resistance and underscores her own strategy of strategic silence and pragmatic conformity.

While she empathizes with his courage, she also recognizes the need for calibrated rebellion—choosing survival and long-term change over immediate protest. In this way, “Antarctic Man” serves as a moral foil, casting Merkel’s approach in sharper relief and reinforcing the internal balancing act that defined her early years.

Vladimir Putin

Though not a character in the conventional sense, Vladimir Putin’s presence in the narrative is profoundly influential. Merkel portrays him not merely as a geopolitical antagonist but as a shrewd and manipulative actor who operates according to a fundamentally different set of assumptions.

Her reflections on their numerous encounters, especially during negotiations over Ukraine and the Minsk agreements, highlight the challenges of engaging with a leader driven by historical revisionism and realpolitik. Putin becomes a symbol of the broader authoritarian impulses Merkel spent her career resisting—not just in Russia, but as echoes within European democracies.

Her handling of Putin is emblematic of her leadership style: firm, methodical, and grounded in the belief that diplomacy must be both principled and realistic.

Benjamin Netanyahu

Netanyahu, the Israeli Prime Minister, appears in Merkel’s narrative as a figure of political friction. Their ideological differences, especially over the feasibility of a two-state solution, underscore Merkel’s enduring commitment to diplomacy and peacebuilding.

While she maintains respect for Israel’s right to self-determination and sovereignty, Merkel’s narrative reflects her discomfort with the hardline settlement policies pursued by Netanyahu’s government. Their relationship is characterized by mutual respect but strained values, offering insights into Merkel’s balancing act between historical responsibility and contemporary ethical positions.

Her steady support for Israeli security, framed within the context of Holocaust remembrance and “reason of state,” contrasts with her simultaneous insistence on human rights and diplomatic dialogue.

Shimon Peres

Shimon Peres emerges as a deeply respected statesman in Merkel’s reflections, a figure who aligns with her ideals of visionary yet pragmatic politics. Their meeting at Sde Boker leaves a lasting impression on her, symbolizing the fusion of innovation, moral responsibility, and civic duty.

Peres’s ideas about trilateral cooperation on water desalinization resonate with Merkel’s vision for international partnerships rooted in sustainable development and diplomatic goodwill. His gentle idealism and historical gravitas provide Merkel with both inspiration and reassurance, anchoring her policy toward Israel in a framework that is forward-looking yet respectful of the past.

Angela Merkel’s Scientific Mentors

Figures like Reinhart Ahlrichs and Nick Handy, Western scientists Merkel encounters during her academic career, represent beacons of intellectual freedom and collaborative spirit. These mentors serve as windows into a world beyond the ideological rigidity of the GDR, offering Merkel not only professional guidance but a glimpse into what science can be when unfettered by political control.

Their mentorship reinforces Merkel’s commitment to empirical inquiry and methodical reasoning, traits that later define her political leadership. Their inclusion in the narrative also speaks to Merkel’s lifelong orientation toward cooperation, evidence-based decision-making, and quiet ambition.

analysis of Themes

Life Under Authoritarianism and the Complexity of Adaptation

Angela Merkel’s formative years in East Germany underscore the psychological and sociopolitical complexity of life within an authoritarian regime. The environment she describes is not only marked by state surveillance and ideological rigidity but also by a strange duality of normalcy and constraint.

Children play in fields, intellectual life thrives in private circles, and families build tight-knit, morally grounded communities—all within a system that simultaneously seeks to monitor, restrict, and manipulate its citizens. Merkel’s childhood and early professional years reflect how individuals learn to adapt to the confines of state control, balancing compliance with internal resistance.

Her decision to censor her speech to preserve educational and professional opportunities illustrates the quiet, calculated decisions that define life under such a regime. The East German state’s bureaucratic density and suspicion toward independent thought demanded a kind of coded behavior—pragmatic, restrained, and deeply self-aware.

Merkel’s experience shows that adaptation is not synonymous with surrender. Rather, it is a deeply personal strategy to maintain one’s identity, integrity, and intellectual curiosity.

Even in the face of political indoctrination, such as mandatory Marxism-Leninism training, she found mental refuge in scientific inquiry and informal social interactions. The emotional sanctuary provided by her family and the Waldhof estate highlights how physical and spiritual spaces can offer resilience and dignity under repressive systems.

Through her life, Merkel demonstrates how people can inhabit authoritarian systems without being defined by them—emerging, in some cases, with an even greater capacity for prudence, empathy, and rational autonomy.

Ethical Responsibility and the Weight of Leadership

Throughout Freedom, Merkel reflects on leadership not as an entitlement, but as an ethical burden carried with clarity, conscience, and consistency. Her choice in 2015 to allow Syrian refugees into Germany, despite political backlash, stands as a pivotal instance of leadership shaped by moral imperatives rather than political convenience.

This decision, made in the context of a continent grappling with rising nationalism and xenophobia, reflects Merkel’s understanding of humanitarian obligation as an intrinsic part of democratic responsibility. Her leadership style—marked by caution, calculated compromise, and quiet resolve—is not shaped by charisma or ideology but by a deeply internalized commitment to doing what is right, even when unpopular.

This extends to her management of the COVID-19 pandemic, where she anchored public communication in scientific evidence and constitutional values, choosing to address the nation in an extraordinary televised speech only when it became absolutely necessary. Merkel does not frame her actions in terms of heroism; rather, she portrays them as the result of ethical reasoning grounded in lived experience and civic duty.

Her conceptualization of “reason of state” is not abstract—it is emotional, historical, and anchored in Germany’s past. Her historic address at the Knesset and her unwavering support for Israel’s security represent a continuation of this principle: that leadership requires moral clarity in both domestic and international contexts.

Her decisions are not reactive; they are deeply deliberated responses to crises, and in that sense, they reflect a rare kind of political integrity that values responsibility over reward.

Personal Identity and Self-Determination

Merkel’s memoir places considerable emphasis on the development of selfhood within constrained systems, portraying personal identity as a continuously evolving construct shaped by both external limitations and internal convictions. As a young scientist in East Berlin, Merkel’s pursuit of knowledge becomes her most radical act of self-definition.

She remains committed to intellectual rigor and ethical conduct even as she is subjected to ideological education, professional surveillance, and state conformity. The evolution of her identity is particularly striking in her recounting of the dissolution of her marriage and her quiet rebellion—squatting in an empty apartment, navigating residency bureaucracy—not as grand political acts but as acts of personal necessity and resolve.

These decisions illustrate a pattern of self-assertion that remains consistent throughout her life: to make meaningful choices within the options available, even when those options are severely limited. The fact that Merkel never saw herself as destined for power—hence the title “I Wasn’t Born Chancellor”—reinforces the memoir’s core message that identity is shaped by experience and choice rather than prophecy or privilege.

Her calm persistence in carving out spaces of freedom, thought, and principle within an authoritarian state formed the bedrock of a political identity rooted not in ambition but in authenticity. This thematic arc, from reluctant dissident to global stateswoman, underscores the idea that identity is not fixed by circumstance but can be reclaimed through consistent, deliberate action—even in the most inhospitable environments.

Historical Memory and Collective Responsibility

In Freedom, historical memory functions not just as background but as a guiding force for Angela Merkel’s worldview and policy priorities. Her reflections on Germany’s Nazi past, particularly during her visit to Yad Vashem and her speech in the Israeli Knesset, reveal how memory serves as both a personal and political compass.

For Merkel, the Holocaust is not a closed chapter but an ever-present moral imperative that informs Germany’s “reason of state” and justifies ongoing support for Israel. This commitment to remembrance is not ceremonial—it is active, reflected in diplomatic decisions, defense policies, and even in humanitarian initiatives aimed at altering the global perception of Israel from one of conflict to one of innovation and partnership.

Merkel’s approach to memory is also pragmatic; she understands the risks of historical amnesia and the seductive narratives of revisionism, especially as witnessed in Vladimir Putin’s justifications for aggression in Ukraine. Her engagement with Eastern European histories—Poland’s Solidarność, Czech dissidents, and the traumatic legacy of the Soviet sphere—demonstrates how personal memory interlocks with larger narratives of European unity, sovereignty, and democratic resilience.

Memory, in this context, is not only a means of reconciliation but a tool for anticipating threats and guiding diplomatic integrity. Merkel’s understanding of collective responsibility goes beyond national borders, extending to humanitarian crises, climate action, and pandemic responses.

In shaping her legacy, she insists that remembering well is not only about the past but about ensuring a future grounded in justice, accountability, and solidarity.

Pragmatism, Rationalism, and Emotional Restraint

One of the most defining features of Merkel’s personal and political identity, as revealed in Freedom, is her embrace of rational pragmatism—an approach that privileges deliberation over drama, restraint over reaction. This mode of thinking is deeply rooted in her background as a scientist and molded further by her life in East Germany, where impulsivity could be dangerous and strategic thinking was essential.

Merkel’s belief in the importance of timing, as exemplified by her metaphorical invocation of Kairos, is not just a reflection on political exit strategies but a governing principle. She values the calibration of action—knowing when to speak, when to wait, when to compromise.

This rationalism is not devoid of emotion; rather, it is a disciplined emotional intelligence that enables her to make hard choices under extreme pressure, whether during the refugee crisis, Brexit, or the pandemic. Her public demeanor—often criticized for being too reserved—is part of this ethic of emotional restraint, a protective layer that enables her to lead amid volatility without being consumed by it.

Merkel’s leadership during the pandemic epitomizes this quality. While others resorted to populism or performative politics, she opted for science-based policies and transparent, if sometimes unpopular, decisions.

Her humility in admitting missteps, such as the Easter lockdown plan, further illustrates that her pragmatism is not rooted in ego but in outcome-oriented governance. In an era often dominated by spectacle and sentiment, Merkel’s quiet rationalism stands as a compelling model of effective and principled leadership.