Ghosts by Dolly Alderton Summary, Characters and Themes

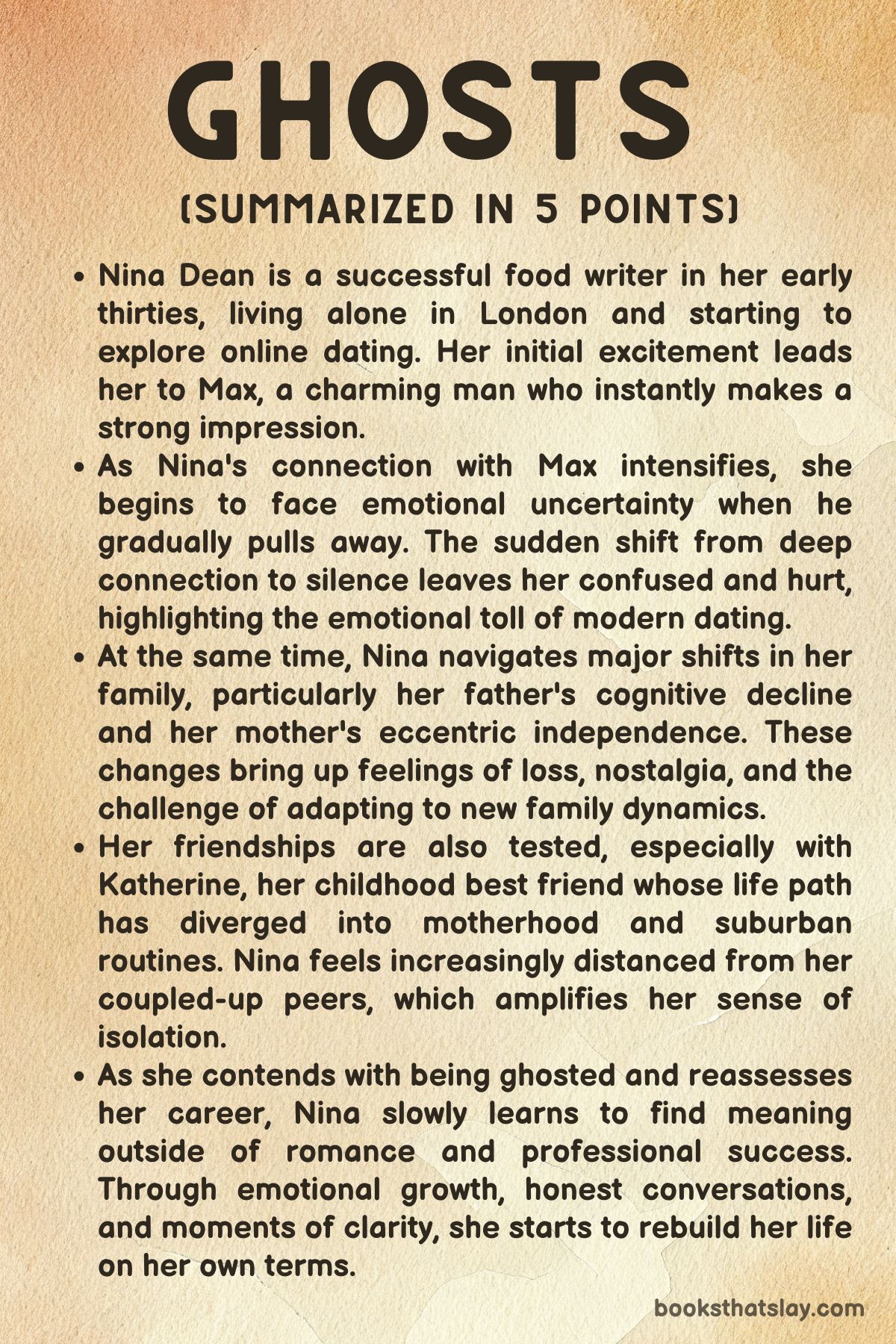

Ghosts by Dolly Alderton is a perceptive and poignant contemporary novel that explores the emotional complexities of modern womanhood, particularly in the context of love, loss, friendship, and personal evolution. Set in present-day London, the story centers around Nina Dean, a successful food writer in her early thirties whose life appears stable from the outside but is quietly undergoing transformation.

Through Nina’s introspective and often humorous lens, the novel examines the subtle grief of ghosting, the slow shift in long-standing friendships, the disorientation of online dating, and the unspoken labor of caregiving for aging parents. With sharp wit and emotional intelligence, Alderton paints a deeply relatable picture of a woman coming to terms with the impermanence and unpredictability of life’s most important relationships.

Summary

Nina Dean is a 32-year-old food writer whose life in North London is filled with comforting rituals and a sense of quiet achievement. Her birthday, typically a time of tradition and joy, now brings with it a twinge of disconnection.

Although she has a well-regarded career, a cozy flat, and supportive friends, she begins to feel out of sync with her social circle, especially as many of her peers enter into marriage and parenthood. At her birthday party, this distance becomes apparent.

She’s the only single woman among a crowd of exhausted parents and distracted spouses. The event is both celebratory and isolating, underscoring her emotional solitude.

Nina’s closest friendships are evolving. Her dynamic with Lola, a glamorous and chaotic single friend, reflects both deep love and mounting tension.

Lola is increasingly desperate to find lasting love, and her emotional highs and lows dominate their conversations. Nina also feels strain with Katherine, her oldest friend, who is now a mother and often misinterprets Nina’s lifestyle as a criticism of her own.

These interactions demonstrate how friendships once built on shared experiences can fray when life paths begin to diverge.

Nina’s romantic life takes a promising turn when she meets Max through a dating app. Their connection is immediate and electric, filled with flirtation, shared interests, and emotional intimacy.

Max charms her with bold declarations, even telling her early on that he plans to marry her. Their relationship blossoms quickly, offering Nina a renewed sense of hope.

They share domestic joys, romantic adventures, and deep conversations. Yet, despite the euphoria, there are hints of emotional unavailability in Max.

He withholds information about his life, such as his father’s illness, and doesn’t fully engage with Nina’s work or her past. These omissions foreshadow the fragility of their connection.

Parallel to this budding romance is Nina’s enduring relationship with her ex-boyfriend Joe. They have transitioned into friendship, but emotional residue lingers.

Conversations with Joe about his upcoming wedding stir conflicting feelings in Nina—gratitude for their shared past, but also melancholy for what’s been lost. Their interactions are filled with nostalgia and quiet longing, illustrating how past loves can remain deeply embedded even after romantic ties are severed.

Family life brings its own challenges. Nina’s father is experiencing early-onset dementia, and her once-stable image of her parents is shifting.

Her mother is reinventing herself with youthful hobbies and even a new name, while Nina tries to hold onto the past. Visits home are increasingly heavy with sadness, especially as Nina watches her father forget once-cherished memories.

Still, there are moments of levity and connection that preserve a sense of familial warmth.

As the months pass, Max suddenly disappears from Nina’s life without explanation. The heartbreak is immediate and profound.

She is haunted by his absence, trying to piece together what went wrong. This emotional ghosting triggers a period of intense self-reflection.

Nina examines her capacity for belief, vulnerability, and the way hope can be manipulated. The disappearance undermines her sense of security and leaves her questioning the validity of their shared experiences.

The emotional toll of ghosting is contrasted with another social engagement: a hen do for Lucy, Joe’s fiancée. Nina, accompanied by Lola, reluctantly attends.

The event is filled with infantilizing games, forced camaraderie, and shallow bonding exercises that highlight her discomfort with performative femininity. The hen do becomes a microcosm for Nina’s deeper frustrations with societal expectations placed on women—particularly the assumption that romantic coupling is the ultimate goal.

Back in her personal life, Nina’s relationship with her neighbor Angelo becomes unexpectedly intimate after months of tension. When he barges into her flat over a misunderstanding, their anger turns into an impulsive, unromantic sexual encounter.

The act is raw and real, born of mutual loneliness rather than affection. In the aftermath, they share stories of heartbreak and loss, forming a quiet camaraderie.

Angelo, too, is grieving a past love, and their brief connection provides a strange but comforting kind of closure.

Lola, meanwhile, is reeling from her own heartbreak after being ghosted by a man she thought she’d marry. Nina, in a moment of fierce loyalty, confronts Lola’s ex to demand accountability, expressing the emotional damage done when men walk away without explanation.

This confrontation speaks to a broader truth within the novel: that emotional cowardice has real consequences, especially for women who invest time, energy, and love into relationships that evaporate without warning.

As Nina continues to navigate her new normal, she finds herself becoming a source of support for others. Katherine reappears one night in emotional distress, overwhelmed by motherhood and seeking solace.

Their night together is messy, honest, and healing. Katherine admits to her struggles with postnatal depression and the fear of losing herself in domestic life.

Their reconnection is a reminder that even strained friendships can be revived through vulnerability and empathy.

The novel concludes on Nina’s next birthday, now a marker of growth rather than loss. She hosts a picnic with friends—Lola, Katherine, Joe, and Lucy—each bringing food and stories that reflect their ongoing bonds.

Her father’s memory continues to decline, but Nina begins to find peace in the fragments he remembers, treating them like abstract but beautiful relics. She and Angelo exchange banter about meat curing and idioms, signaling a new phase of neighborly respect.

Though Max’s disappearance remains unresolved, Nina has grown. She acknowledges the uncertainty of the future, but with renewed clarity about what she values: the constancy of friendship, the small joys of independence, and the resilience of hope.

She no longer needs definitive answers to feel whole. As she blows out her candles, surrounded by chosen family, she embraces the idea that life’s ghosts—whether in love, memory, or identity—may never leave completely, but they don’t have to haunt her.

Characters

Nina Dean

Nina Dean is the emotional and intellectual anchor of Ghosts, navigating the intricacies of adulthood with a mixture of self-awareness, vulnerability, and sharp observational wit. As a thirty-something food writer in London, Nina is successful in her career, introspective about her past, and quietly yearning for stability and love in a world increasingly marked by emotional ambiguity.

She is deeply nostalgic, valuing traditions like birthday rituals and childhood comforts, which serve as a means to hold onto a sense of continuity amid the unpredictable shifts in her life. Nina’s internal world is rich and turbulent; she is constantly balancing her external composure with internal anxieties.

Her relationships define her character arc: the ghosting by Max destabilizes her confidence, her enduring but complicated friendship with Lola reflects her compassion and patience, and her care for her father reveals a deep emotional maturity rooted in love and grief. Through her candid narration, Nina emerges as a woman caught between independence and the longing for connection, deeply aware of life’s absurdities, and yet still capable of hope.

Lola

Lola is Nina’s closest friend and emotional counterpart—flamboyant, chaotic, and fiercely romantic. Where Nina tends toward intellectual analysis and emotional restraint, Lola moves through the world with an open heart, eager for love and meaning in a culture that often dismisses such longing as foolish.

She is frequently embroiled in intense but unstable romantic affairs, driven by her yearning to be seen and valued. Her spirituality, belief in cosmic signs, and obsession with dating app interactions serve both as coping mechanisms and expressions of her emotional excess.

Lola’s vulnerability is disarming, and her insecurities around being single reveal the social pressures placed on women to find fulfillment in romantic partnership. Despite her own heartbreak, Lola is unwavering in her support for Nina, offering levity, loyalty, and a safe space for shared grief.

She embodies the emotional labor and resilience of women who continue to believe in love despite repeated disappointments, and her arc underscores the book’s exploration of the delicate power of female friendship.

Max

Max, the elusive romantic interest, is at once charming, magnetic, and frustratingly unreadable. His initial appearance in Nina’s life is marked by intensity and apparent sincerity, declaring on their first date that he intends to marry her.

This boldness sweeps Nina into a passionate romance that feels like the answer to her long-held hopes. However, Max’s emotional opacity soon becomes evident.

He withholds personal details, avoids vulnerability, and ultimately disappears without explanation, embodying the very phenomenon the book is titled after—ghosting. Max’s disappearance is not just a plot device but a profound emotional rupture that calls into question Nina’s understanding of love, trust, and modern masculinity.

He becomes a symbol of unaccountable behavior and the consequences of emotional evasion, highlighting how men are often permitted to retreat from intimacy without explanation or remorse. Max is not just a failed relationship but a catalyst for Nina’s deeper reckoning with loneliness and resilience.

Joe

Joe, Nina’s ex-boyfriend, represents a different kind of romantic loss—one that is conscious, mutual, and ongoing. Their relationship ended amicably after seven years, yet the emotional tether between them remains.

Joe’s new life with Lucy, including marriage and fatherhood, contrasts sharply with Nina’s continued singlehood and introduces complex feelings of comparison, regret, and lingering affection. Despite their efforts to remain friends, their interactions are often loaded with subtext and the unspoken ache of shared history.

Joe embodies the path not taken—a life of stability and traditional milestones that Nina once envisioned for herself. His presence in the novel offers a foil to Max’s ghostliness: where Max disappears, Joe is physically present but emotionally out of reach.

Nina’s conversations with Joe force her to confront not just what she has lost, but also what she has consciously chosen to forgo in pursuit of personal freedom and authenticity.

Katherine

Katherine, Nina’s childhood friend, provides a window into the isolating and often unspoken realities of motherhood. Initially appearing as the archetype of domestic success—married with children and a home—Katherine’s emotional breakdown reveals the cracks beneath the surface.

She is overwhelmed, disillusioned, and disconnected from the identity she once shared with Nina. Their overnight reunion becomes a reckoning, exposing the silent competition and mutual judgment that have crept into their friendship.

Katherine’s vulnerability and honesty allow the two women to reconnect on deeper terms, showing how friendship can evolve through honesty and forgiveness. Her story highlights the societal expectation for women to find total fulfillment in motherhood, while ignoring the personal toll it often takes.

Katherine’s emotional complexity adds depth to the novel’s exploration of friendship, showing how even the most established bonds must be renegotiated as life changes.

Angelo

Angelo, Nina’s downstairs neighbor, initially appears as a figure of annoyance and mystery. His unneighborly behavior and emotional aloofness create a backdrop of simmering tension, which explodes in a surprising moment of emotional and physical intimacy.

Their unexpected sexual encounter, grounded in mutual loneliness and grief, provides a raw and unromantic but deeply human connection. Angelo’s story of lost love and his attempt to preserve his past through meat-curing rituals serves as a poignant metaphor for memory, mourning, and identity.

His interaction with Nina becomes one of mutual recognition—two solitary people attempting to find meaning and relief in a disjointed world. Angelo is not a traditional romantic figure but a symbol of the strange, serendipitous ways people can connect through shared vulnerability.

He stands as a quiet counterpoint to both Joe and Max—emotionally present, if not entirely available, and emblematic of healing that does not rely on permanence.

Nancy (Mandy) and Bill

Nancy, Nina’s mother, represents the complexities of reinvention later in life. In the face of her husband Bill’s cognitive decline, she clings to personal transformation—changing her name, adopting new hobbies, and diving into modern feminism.

Her behavior sometimes feels alienating to Nina, who is trying to preserve the past and her father’s identity. Nancy’s reinvention is both a coping mechanism and a bid for control amid the chaos of loss, showing the multiplicity of grief responses.

Meanwhile, Bill, Nina’s father, is a tragic figure—once intellectually vibrant, now fading into dementia. His decline is heartbreaking, marked by disjointed memories, emotional confusion, and rare moments of clarity that pierce through the fog.

Through Bill, the novel addresses the erosion of identity and the painful inversion of the parent-child relationship. Together, Nancy and Bill embody the themes of change, memory, and endurance in the face of aging, providing emotional ballast to Nina’s personal journey.

Themes

Ghosting and the Emotional Toll of Disappearance

In Ghosts, the experience of being ghosted is not treated as a passing annoyance but as a deeply destabilizing emotional rupture. Max’s abrupt disappearance from Nina’s life after promising intimacy and a future together is portrayed not just as a heartbreak, but as an existential erosion of trust and certainty.

What makes this act so psychologically punishing is its silence—there is no rupture to mourn, no fight to contextualize, no closure to grasp. The book shows how ghosting is more than rejection; it’s a kind of erasure that leaves the person questioning not only the relationship but their very perception of reality.

Nina is left haunted by Max’s absence, not just emotionally but physically—his ghost lingers in text threads, routines, and shared spaces that once felt sacred. The absence becomes a character of its own, invading her days with what-ifs and lingering dread.

The emotional aftermath is compounded by a culture that trivializes this kind of abandonment, particularly when it happens to women over thirty who are expected to be “over it. ” Instead, Nina’s experience affirms how the phenomenon of ghosting fractures the psyche, mirroring the destabilization often associated with grief, yet lacking societal permission to be grieved.

Her interactions with Lola and Jethro further emphasize this point, reinforcing how emotionally irresponsible behavior by men is normalized, even rewarded, while women are left to carry and process the emotional burden alone.

Female Friendship and Emotional Labor

Female friendship in Ghosts is a site of both sanctuary and strain. Nina’s relationships with Lola and Katherine are deeply intimate but also challenged by the different paths their lives have taken.

Katherine’s new motherhood renders her nearly incomprehensible to Nina, who watches as her oldest friend crumbles under the pressure of parenting but can no longer reach her with the same ease. Yet when Katherine finally breaks down and seeks refuge with Nina, their bond is rekindled not through nostalgia, but through shared vulnerability.

Similarly, Nina’s friendship with Lola, who remains fiercely single and emotionally impulsive, is both affirming and exhausting. Lola clings to Nina for emotional validation and romantic advice, often at the cost of Nina’s own space and peace.

The novel is keenly aware of how women, particularly in their thirties, are expected to provide constant emotional labor not just in romantic partnerships but also within friendships. Nina’s role as comforter, interpreter, and stabilizer is nearly unrelenting.

The women in her life bring their heartbreak, their parental crises, their loneliness, and Nina absorbs it all, even as she struggles with her own unspoken grief. These friendships, while crucial to her survival, are not always reciprocal.

The book presents female friendship as deeply loving but often imbalanced terrain, marked by care, codependence, and emotional generosity that can be as depleting as it is sustaining.

Aging, Memory, and Parental Decline

The slow deterioration of Nina’s father due to early-onset dementia is one of the most poignant and painful threads in Ghosts. The narrative explores how memory becomes a battleground for love, identity, and grief.

Nina clings to her father’s quirks—his affection for sentimental trinkets, his wit, his small rituals—as a way to anchor herself to the version of him that once existed. The scenes with her father are subtle but devastating, portraying the erosion of personality and the strange intimacy of watching someone you love become unrecognizable.

Nina’s helplessness is magnified by her mother’s strange reinvention of herself—changing her name, joining feminist book clubs—at a time when Nina longs for familiarity and stability. Her father’s decline strips Nina of the traditional role of daughter and forces her into a role of quiet caregiving and emotional interpreter.

She must console her mother, comfort the carers, and preserve what fragments she can of the man her father used to be. Even moments of lucidity—like their visit to the Picasso exhibition—are laced with melancholy, because they only underscore what has been lost.

The book treats aging not as a distant concern but as an immediate, destabilizing reality that reshapes familial relationships and erodes personal identity. Nina’s experience reflects a generational moment when adulthood no longer brings clarity or certainty but requires confronting the fragile, sometimes disorienting transitions of those we love most.

Romantic Idealism vs.

The initial stages of Nina’s relationship with Max are painted with euphoria, electricity, and optimism. His bold declaration of intent—to marry her—is intoxicating, seeming to offer the romantic certainty that eluded Nina in a world of half-hearted texts and ambivalent flings.

But Ghosts methodically dismantles the illusion of romantic idealism, replacing it with a sobering portrait of emotional realism. Max’s charisma and confidence quickly give way to evasiveness and detachment.

His emotional withholding—whether in refusing to share details about his family or failing to engage with Nina’s memoir—becomes the silent engine of their unraveling. What Nina initially interprets as romantic mystery soon reveals itself to be a defense mechanism, a refusal to be known fully.

The book captures the painful moment when desire turns into doubt, when intimacy becomes suspect, and when a woman realizes she is emotionally alone in a relationship she thought was mutual. Nina’s attempt to reconcile her memories of Max with his abrupt disappearance illustrates the cognitive dissonance that often accompanies heartbreak.

She oscillates between mourning what was and questioning whether it was ever real. The novel does not condemn her romantic optimism but rather contextualizes it within a world that often punishes women for wanting love too openly.

In doing so, it underscores the courage it takes to remain hopeful amid the wreckage of emotional disappointment.

The Crisis of Identity in Modern Adulthood

Nina’s experience of her thirties is marked by a quiet existential crisis, one that Ghosts explores through the subtle shifts and ruptures in her life. She is successful, independent, and surrounded by friends, yet she feels increasingly disoriented.

The life she imagined for herself no longer matches the reality she inhabits, and the benchmarks of adult success—homeownership, career, romantic partnership—provide diminishing emotional returns. Her singlehood, once a symbol of autonomy, becomes a source of social discomfort.

Friends couple off and start families, and Nina is left in a liminal space: not young enough to be carefree, not old enough to be settled. This in-betweenness is magnified during social events like her birthday party or Joe’s wedding, where she oscillates between belonging and alienation.

Nina’s work, particularly her cookbooks, once rooted her identity, but even this begins to feel fragile amid the emotional turbulence of her personal life. She watches as her parents age, her friendships evolve, and her romantic prospects falter, all while struggling to maintain a cohesive sense of self.

The novel captures how adulthood can bring not just external achievements but internal disarray—a sense that life is happening to you rather than being directed by you. Nina’s crisis is not dramatic or overt; it is incremental, marked by tiny humiliations, quiet revelations, and moments of private despair.

Her search for meaning and self-understanding reflects a broader cultural uncertainty about what it means to be “grown up” in an era where stability feels more elusive than ever.