Girl Dinner Summary, Characters and Themes

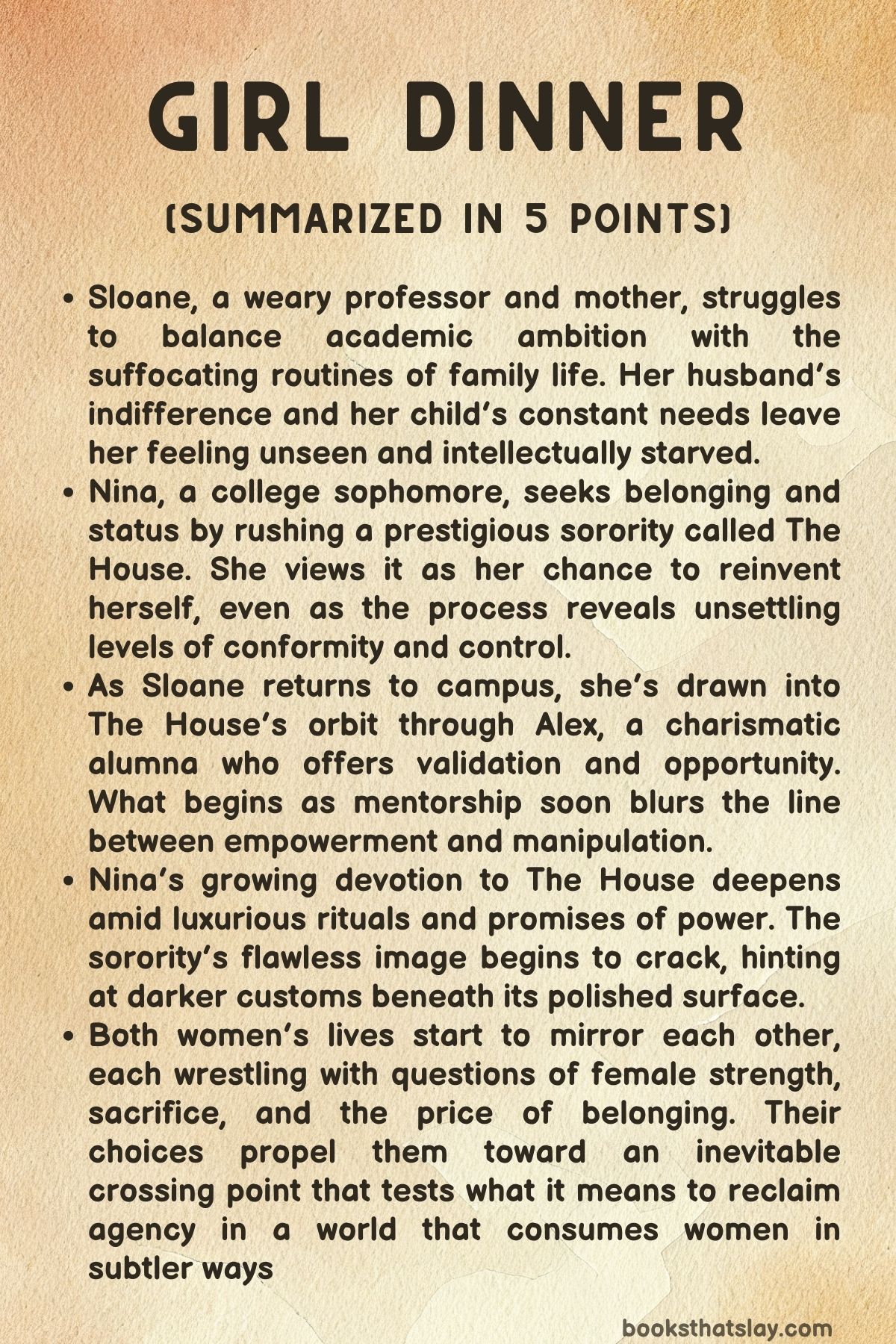

Girl Dinner by Olivie Blake is a darkly satirical and psychological exploration of modern womanhood, ambition, and hunger—for recognition, power, and identity. The novel follows two women at different stages of life: Sloane, an exhausted academic and new mother questioning her choices, and Nina, a college student desperate for belonging in an elite sorority known as The House.

As their lives intersect, both are drawn into a world of ritual, secrecy, and transformation, where empowerment takes a disturbing and literal form. Through biting social commentary and chilling symbolism, Blake dissects the pressures of female perfection and the price of reclaiming control.

Summary

The story begins with Sloane, a sociology professor navigating the suffocating routines of motherhood and marriage. Over dinner with her husband Max and their toddler, Isla, she reflects on how domestic life has eroded her identity.

Her body still aches from childbirth, and her career has stagnated since she followed Max to his university job. As he scrolls on his phone, she cooks, cleans, and soothes their child, simmering with resentment.

This monotonous evening sets the tone for her growing frustration—a brilliant woman reduced to repetition and servitude.

The narrative then shifts to Nina, a sophomore returning to campus for sorority recruitment. Her older sister, Jasleen, disapproves of Greek life, but Nina views The House, a powerful and exclusive sorority, as her ticket to reinvention and future success.

The recruitment process feels artificial, yet she’s drawn to the perfection of its members—especially the charismatic president, Fawn Carter. Nina’s fascination is not just with their beauty but their aura of control.

When Fawn personally greets her, Nina feels chosen, as though her life is about to change.

Sloane returns to teaching after maternity leave, struggling to reconcile her intellectual ambitions with maternal guilt. Isla cries at daycare drop-off, and Sloane feels like a monster for leaving her.

At work, she stumbles through lectures, her sharpness dulled by exhaustion. When she meets her new teaching assistant, Arya, she’s disoriented by his youth and confidence, an uncomfortable reminder of the woman she used to be.

Meanwhile, Max remains detached, offering practical sympathy but no real support. Online, Sloane doomscrolls through idealized portrayals of domestic bliss, both disgusted and seduced by them.

Then she meets Alex, a magnetic woman in a red blazer, who befriends her outside the daycare and invites her for coffee. Their instant connection feels like relief—a glimpse of adult companionship.

At the same time, Nina immerses herself in rush week’s rituals, befriending Dalil, a sharp but skeptical freshman. Both are drawn deeper into The House’s mysterious culture.

The members, particularly Fawn and her lieutenant Tessa, radiate an almost supernatural unity. They speak about sisterhood as a calling, not a club, invoking loyalty and sacrifice.

When Nina learns she’s been invited back, she feels chosen—anointed rather than selected. Her excitement grows when she locks eyes with her philosophy professor, whose lecture on free will mirrors her own craving for agency.

Sloane’s connection to The House strengthens when she’s invited by Alex and alumna Britt Landau to become the sorority’s faculty advisor. At first hesitant, she’s persuaded by their charm and the promise of networking.

For the first time in years, she feels seen. Her husband encourages her to accept, hoping it might restore her confidence.

Sloane agrees, unaware that this decision will entangle her with the organization in ways far darker than she imagines.

In a separate thread, Sloane’s marriage continues to erode. She and Max attempt intimacy, but the act is mechanical, sustained only by her imagination of Arya.

Her internal life grows increasingly fractured between maternal guilt, sexual repression, and academic futility. Meanwhile, Nina’s induction into The House begins in earnest.

She and Dalil receive binders filled with songs and rituals to memorize. Fawn’s mantra—“live deliciously”—becomes the group’s moral compass, urging indulgence and unity.

The Monday dinners, elaborate and ritualized, seem sacred. The women eat ravenously, their conversations coded, their movements synchronized.

When Nina mentions cramps, she’s told she won’t need to worry about that again—a hint of something sinister beneath their perfection.

As weeks pass, Sloane starts interviewing alumnae for a research project about The House. Each woman she meets exudes grace and composure, crediting the sorority for her success.

Yet their eerily identical manner unsettles her. Alex’s talk of empowerment feels hollowly rehearsed.

When Sloane’s curiosity leads her to Caroline Collins—a controversial influencer known as The Country Wife—she discovers a darker truth. Caroline welcomes her with wine and dinner, defending her public image as a “traditional” homemaker while claiming that power, not virtue, drives success.

During the meal, Caroline serves her “heart” and hints that The House’s rituals involve literal consumption. When Sloane recoils, Caroline taunts her—“If you think I’m bad, wait until you see them.”

Alex soon appears, furious at Caroline, and forces Sloane to leave. In the car, pressed by Sloane’s questions, Alex reveals the horrifying truth: The House practices ritualistic cannibalism, consuming human flesh as a form of communion and empowerment.

She justifies it as symbolic—a reclamation of what patriarchy has taken from women. Sloane is horrified but also entranced.

The idea that consuming strength could be inherited tempts her, especially as a mother desperate to protect her child.

Meanwhile, Nina’s initiation reaches its climax. Blindfolded, she drinks from a goblet that tastes of blood.

She wakes the next morning radiant—her body strong, her pain gone. Fawn tells her she has consumed vengeance and power.

Nina accepts it, transformed from uncertain girl to devoted acolyte.

Time passes. The House’s dinners grow more elaborate, culminating in plans for the annual solstice ritual.

Each member must bring a “candidate”—a guest to be drugged and sacrificed. Nina is disturbed but rationalizes it as symbolic.

When internal politics threaten Fawn’s presidency, Nina is manipulated into running against her, becoming a pawn in the power struggle. Fawn’s fury shatters their once-intimate bond.

In a moment of twisted devotion, Nina decides to bring Dalil as her “candidate,” believing it will prove her loyalty.

As preparations unfold, Sloane’s mental state deteriorates. She visits Caroline and Alex again, oscillating between horror and fascination.

They insist the ritual brings strength and immunity from weakness. Broken by years of dismissal and exhaustion, Sloane succumbs to the same hunger that once repulsed her.

In a feverish act, she kills and feeds human flesh to her daughter, convinced it will make Isla powerful.

The novel reaches its climax at the solstice dinner. The sisters gather, each with their candidate—men representing power or betrayal.

Fawn brings her former professor as an act of revenge. Nina, witnessing the brutality, realizes Fawn’s motivations are selfish rather than symbolic.

When the vote arises over who will be consumed, Nina offers herself, declaring her love for The House. Though spared, her gesture restores unity.

The sisters proceed to feast, devouring Tripp, another member’s boyfriend, as sacrifice.

Outside, Sloane approaches The House with a stun gun, intent on saving the innocent or joining the devouring—perhaps both. Inside, the women eat in euphoric silence.

Later, Sloane prepares a rich meal of Bolognese at home, feeding it to Isla and Max, who eat gratefully, unaware of its source. As she watches them, Sloane feels fulfilled at last, believing she has nourished her family and reclaimed her power.

In the haunting final image, Jasleen’s phone buzzes unanswered on the pavement outside The House. Inside, everyone has eaten, and the cycle continues.

Characters

Sloane

Sloane is the emotional and intellectual core of Girl Dinner, a woman torn between the demands of motherhood, academia, and the fading remnants of her own ambition. Once a sharp and driven sociology professor, she now finds herself reduced to an exhausted adjunct, juggling diapers, dishes, and lectures while her husband Max thrives professionally.

Her inner world brims with bitterness, guilt, and yearning—a constant push and pull between self-erasure and self-reclamation. Through Sloane, Olivie Blake explores the modern mother’s dilemma: the loss of identity under the guise of domestic love.

Sloane’s physical and emotional depletion mirrors the decay of her marriage and intellect; even her fantasies—directed toward her young teaching assistant, Arya—reveal her longing to feel alive again. As she becomes entangled with The House through Alex’s invitation, her intellectual curiosity morphs into obsession.

The allure of the sorority’s power seduces her, not because she craves evil, but because she craves autonomy. Her descent into cannibalism—feeding her daughter human flesh—is not a grotesque act of violence but a tragic perversion of maternal devotion, an attempt to reclaim power in a world that has stripped her of it.

Sloane’s character arc thus becomes a chilling study in how patriarchal exhaustion and unmet desire can twist even intellect into monstrosity.

Max

Max serves as a foil to Sloane’s unraveling—an emblem of quiet male privilege and complacency. He is a well-meaning but emotionally absent husband, more engaged with his phone and career than with his wife’s deteriorating spirit.

His practicality often comes off as condescension, masking his refusal to see Sloane’s suffering as real or consequential. Though he claims to support her ambitions, his actions subtly reinforce her subordination—encouraging her to take on The House advisory role not out of empathy but to alleviate his own discomfort.

Max embodies the modern patriarch cloaked in progressivism: he believes himself egalitarian yet perpetuates imbalance by doing nothing to change it. By the novel’s end, his physical frailty contrasts with Sloane’s monstrous empowerment, inverting their initial dynamic.

When he eats the meal Sloane prepares, his submission completes the grim irony—his dependence on her, literalized through consumption, mirrors her long-standing emotional starvation.

Isla

Isla, though a toddler, is the haunting symbol of both creation and consumption in Girl Dinner. She represents the cycle of inheritance—what mothers pass to daughters beyond milk and lullabies.

To Sloane, Isla is both beloved and burdensome: a mirror of her own confinement and the reason she continues to endure it. Her cries at daycare and refusals at the dinner table magnify Sloane’s guilt and helplessness.

Yet, by the novel’s close, Isla becomes the vessel of Sloane’s distorted salvation. The act of feeding her the human-infused meal transforms Isla into the inheritor of her mother’s dark empowerment.

Through this grotesque communion, Isla embodies the next generation’s entanglement in cycles of feminine sacrifice and survival.

Nina

Nina’s story runs parallel to Sloane’s, depicting another woman caught between aspiration and indoctrination. A sophomore desperate to reinvent herself, Nina seeks refuge in The House, believing it to be a sanctuary of excellence and belonging.

Her initial naivety and hunger for approval drive her toward the cult-like sorority, where beauty, ambition, and dominance masquerade as empowerment. Nina’s admiration for Fawn and fascination with the group’s ritualized perfection expose her yearning for transformation—a desire to shed weakness and become part of something divine.

Her eventual acceptance of cannibalistic rituals reflects her tragic evolution: the girl who wanted to belong becomes the woman who will consume and be consumed for belonging’s sake. Yet, Nina’s final act of nominating herself as dinner reclaims her agency in a twisted way—an assertion of choice within coercion.

She becomes both martyr and monster, illustrating Blake’s central paradox: in the pursuit of female power, the line between liberation and destruction blurs irreversibly.

Dalil

Dalil is both Nina’s friend and moral counterweight, embodying skepticism, independence, and an unwillingness to fully submit. She mocks the superficiality of sorority life yet is drawn to The House’s allure, revealing her own contradictions.

Her intelligence and realism make her stand apart from Nina’s blind idealism. However, her perceived inconsistency—being labeled a “quitter”—becomes her undoing in a system that values obedience over authenticity.

Dalil’s trajectory exposes how women who resist the collective myth of sisterhood are often sacrificed, literally and metaphorically, to sustain it. Her eventual role as Nina’s “candidate” for the solstice dinner crystallizes the tragedy of women pitted against each other in hierarchies disguised as empowerment.

Alex

Alex is the novel’s most enigmatic and chilling figure—a charismatic mentor, sorority alumna, and evangelist of The House’s philosophy. She personifies seductive authority, presenting cannibalism not as horror but as evolution, a reclamation of vitality stolen by patriarchy.

Her composure, beauty, and maternal warmth mask predation; she nurtures and consumes with equal grace. For Sloane, Alex represents everything she once aspired to be—intelligent, composed, in control—and thus becomes the perfect manipulator.

Alex’s rhetoric of sisterhood and empowerment twists feminist ideals into justification for violence, transforming collective womanhood into a mechanism of domination. Through her, Blake dissects how charismatic female leadership can perpetuate the same oppressive systems it claims to dismantle.

Alex’s calm acceptance of monstrosity makes her the embodiment of the novel’s central thesis: power, once tasted, is indistinguishable from hunger.

Fawn Carter

Fawn is the embodiment of The House’s divine rot—beautiful, commanding, and terrifyingly devoted. As president, she wields charisma like a weapon, uniting her sisters through ritualized cruelty and charm.

To Nina, Fawn is both idol and lover, the living proof that devotion yields transcendence. Yet Fawn’s power is deeply performative; her authority depends on fear, adoration, and spectacle.

When challenged, her insecurities surface as vindictiveness, revealing her rule as a desperate defense against irrelevance. Fawn’s obsession with control and purity drives her to manipulate others, particularly Nina, whom she alternately seduces and destroys.

Her downfall in the election mirrors the inevitable decay of unchecked female hierarchy—a reminder that even within matriarchal power, corruption festers.

Tessa

Tessa bridges the extremes of devotion and doubt within The House. As Nina’s mentor, she initially appears supportive and rational, softening the cultish edges of the organization.

Yet her complicity deepens as the truth unfolds; she justifies the rituals as necessary, framing violence as symbolic empowerment. Her pragmatism contrasts with Fawn’s fervor, positioning her as the voice of balance within madness.

However, by normalizing atrocity, Tessa exemplifies how intellectual rationalization perpetuates evil. She mentors Nina with sincerity but cannot resist the gravitational pull of collective ideology.

Her tragedy lies in her inability to see that moderation within monstrosity is still complicity.

Caroline Collins (“The Country Wife”)

Caroline is the defector, the apostate whose departure from The House exposes its darkest truths. Her outward persona—a traditional homemaker influencer—masks sharp cynicism and a self-serving pragmatism.

She rejects Alex’s idealism, viewing power as a currency to be manipulated rather than moralized. Her confrontation with Sloane over dinner—serving her “heart”—is the novel’s moral crux, a grotesque parable about the price of survival.

Caroline’s embrace of patriarchal aesthetics for profit and her simultaneous participation in feminine violence make her the most paradoxical figure in the story. She forces Sloane—and the reader—to question whether there is any form of power not rooted in consumption.

Themes

Motherhood and the Loss of Identity

In Girl Dinner, motherhood is portrayed as both a sacred responsibility and a suffocating confinement. Through Sloane’s experiences, the novel presents motherhood as a consuming force that erodes individuality while demanding constant self-erasure in the name of care and sacrifice.

Sloane’s life is defined by exhaustion and repetition, her once-bright academic career dimmed by sleepless nights, domestic chores, and the silent expectations placed upon women to bear both emotional and physical labor without complaint. The dinner scenes between Sloane, Max, and their toddler Isla exemplify this erosion of identity—the woman who once lectured on sociological theory now measures her worth through tantrums soothed and meals prepared.

Even her body becomes a site of estrangement; childbirth has transformed it into something unrecognizable, still aching, still marked by sacrifice. Yet, the novel does not treat motherhood with disdain—it exposes the brutal tenderness of it, the contradiction of loving one’s child while mourning one’s autonomy.

When Sloane feeds her daughter in the final scenes with the horrific Bolognese, her act embodies the twisted culmination of maternal devotion: the desperate attempt to nourish and empower a child through any means possible, even violence. In this way, the book questions whether motherhood can ever exist free from loss—of self, of freedom, or of moral certainty.

Sloane’s journey illustrates how motherhood, under societal and patriarchal constraints, becomes both a site of reverence and ruin, a hunger that devours the woman herself.

Female Ambition and Power

Ambition in Girl Dinner carries a dual edge—it is both liberation and damnation. For Sloane, ambition is a memory, dulled by diapers and disillusionment.

For Nina, it is a feverish dream, embodied by the gleaming perfection of The House. Both women chase empowerment in systems that quietly demand their submission.

Sloane once imagined academia as a space for intellect and progress, but discovers its hierarchy mirrors the same patriarchy she studies. Nina envisions sorority life as an entry point to influence, but the sisterhood she joins feeds on control and conformity, masquerading as empowerment.

The House seduces with promises of excellence and unity, turning ambition into ritual, competition into communion. What begins as a quest for belonging transforms into an initiation into literal consumption—the devouring of bodies to maintain beauty, success, and vitality.

This grotesque metaphor reflects the cost of female ambition in a world that commodifies women’s labor and appearance. By depicting women who must consume others—figuratively and literally—to ascend, the novel asks whether power within such a system can ever be pure.

Sloane’s final act of feeding her child human flesh parallels Nina’s participation in The House’s feast: both seek power through acts of moral transgression, convinced they are reclaiming control. Yet, their empowerment is tainted by the very structures they sought to overcome.

In Girl Dinner, ambition does not free women from oppression—it mutates under its weight, revealing how hunger for power, when starved too long, can become indistinguishable from hunger itself.

Sisterhood and Corruption of Female Solidarity

The novel’s portrayal of sisterhood begins as an intoxicating ideal and unravels into something chillingly transactional. The House, which first appears to embody female unity and mutual upliftment, gradually reveals itself as a structure built on hierarchy, secrecy, and sacrifice.

Within its rituals of blood and communion lies a dark satire of modern feminism’s surface-level empowerment—the kind that markets perfection, cohesion, and “having it all” while quietly enforcing conformity. Nina’s devotion to The House grows from admiration to obsession, as belonging becomes synonymous with survival.

The women’s synchronized movements, their identical poise and success, reflect how individuality is devoured in the name of collective strength. What masquerades as solidarity becomes complicity in violence.

Similarly, Sloane’s friendship with Alex mirrors this corruption of support; Alex’s mentorship disguises manipulation, her kindness a lure into moral surrender. Yet, the novel avoids simplistic condemnation.

It suggests that such corruption arises not from inherent female cruelty but from desperation in a world where genuine power is scarce and conditional. The women’s rituals—eating flesh, pledging loyalty, silencing dissent—are grotesque exaggerations of the ways women are socialized to consume and compete against one another.

The tragedy lies in how their desire for safety and sisterhood transforms into self-destruction. By the novel’s end, the circle of women stands complete but hollow, united by blood and fear, their communion a haunting reflection of solidarity twisted into subjugation.

The Body as a Site of Power and Consumption

Throughout Girl Dinner, the body is not merely flesh—it is currency, battleground, and altar. The women’s physical experiences—childbirth, beauty rituals, sexual encounters, and feasts—illustrate how power manifests through corporeal control.

For Sloane, her body is both a source of resentment and a reminder of what she has lost. Her postpartum pain, sexual disconnection, and exhaustion represent the body’s rebellion against the ideal of the perfect mother.

In contrast, The House sanctifies the body as the vessel of supremacy. Its members worship physical perfection—flawless skin, eternal youth, synchronized beauty—achieved through the grotesque act of consuming human organs.

This literalization of societal pressures exposes how women are taught to feed on themselves and others to maintain desirability and relevance. When Nina’s menstrual pain disappears after the initiation, her relief masks her submission to an unnatural order—a body freed from weakness at the cost of humanity.

The cannibalism functions as a horrifying metaphor for how society consumes women’s vitality, how success demands bodily sacrifice disguised as empowerment. Sloane’s final act—feeding her daughter human flesh—represents the ultimate corruption of maternal nourishment, transforming the sacred into the monstrous.

Yet, it also reflects a perverse reclamation of agency: if her world demands consumption to survive, she will decide what and whom to consume. In this way, the novel collapses the boundary between power and appetite, showing that in a system that feeds on women, the body becomes both weapon and offering, its hunger both curse and creed.

Domesticity, Desire, and the Illusion of Control

Domestic spaces in Girl Dinner operate as both sanctuaries and prisons. Sloane’s kitchen, the setting of the novel’s opening dinner, embodies this duality—a space of nourishment turned arena of quiet resentment.

Every act of cooking and cleaning becomes symbolic of unacknowledged labor, of intellect reduced to routine. Her desire, both sexual and intellectual, festers beneath the surface, redirected into fantasies about her teaching assistant or idealized motherhood content online.

This interplay between repression and yearning underscores how domesticity masquerades as stability while eroding autonomy. For Nina, the sorority house serves a similar purpose: a domestic ideal wrapped in grandeur, where women perform unity under strict rules.

The House, with its curated aesthetics and ritualized meals, transforms domestic order into cultic control. Both women inhabit spaces designed to comfort but structured to confine, where control is illusionary—granted only when they submit to prescribed roles.

When Sloane imagines liberation through her connection with Alex, or Nina through her devotion to Fawn, their desires are manipulated, redirected into service of larger systems that profit from their compliance. The illusion of control becomes the novel’s most insidious deception.

Every meal, from the toddler’s dinner to the solstice feast, reinforces that domestic rituals—those meant to nourish—can conceal dominance and submission. By the end, both women seize agency in acts of horrifying defiance, yet their liberation remains tainted.

Girl Dinner thus exposes domesticity not as a private refuge but as the stage upon which power, desire, and hunger perform their endless masquerade.