Girl Next Door by Rachel Meredith Summary, Characters and Themes

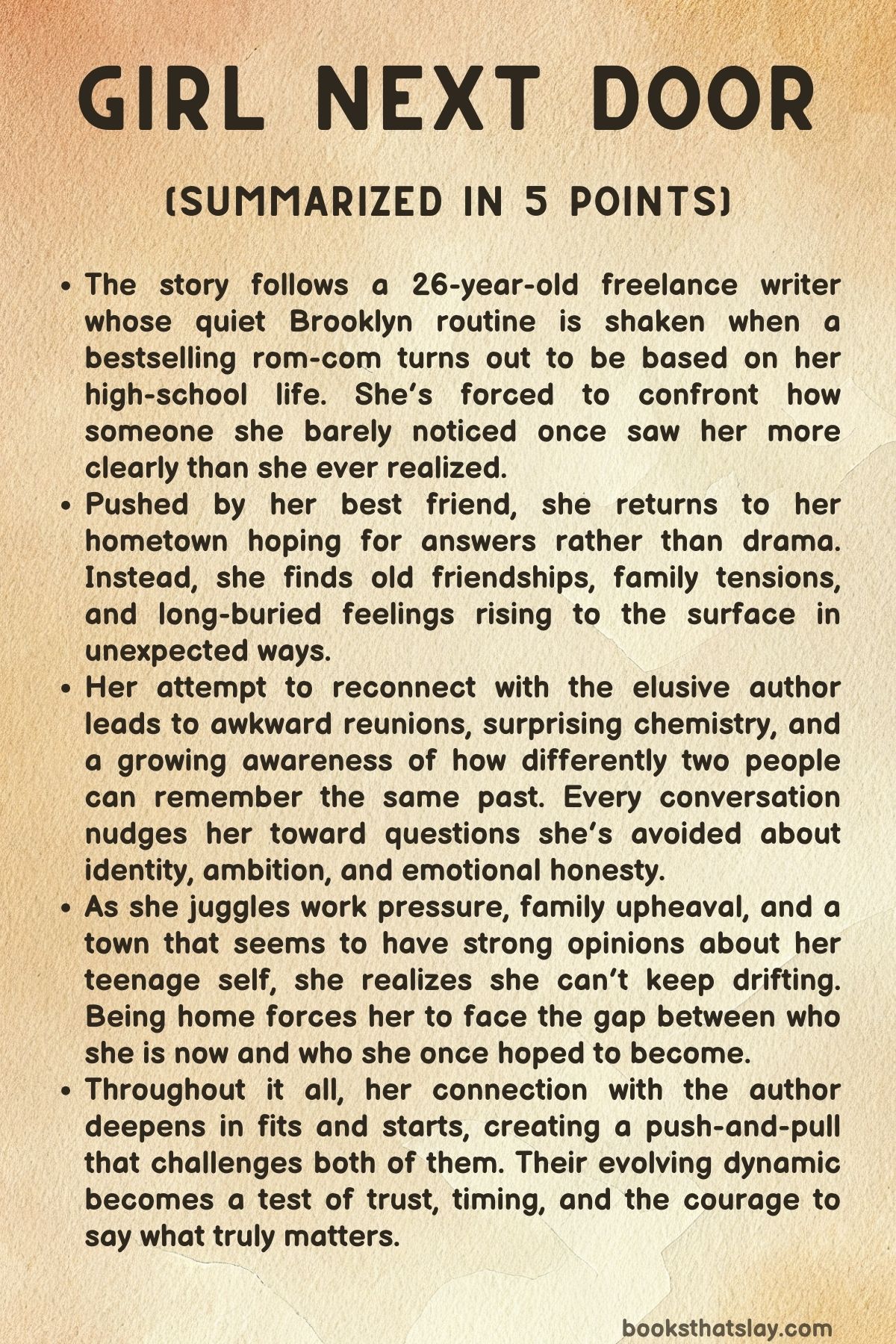

Girl Next Door by Rachel Meredith is a contemporary queer coming-of-age story about identity, privacy, and the messy process of growing up long after high school ends. It follows a 26-year-old freelance writer who discovers that her childhood neighbor has written a blockbuster romance based on their shared past, reshaping memories she never expected to revisit.

As she returns to her hometown, she confronts old friendships, unresolved feelings, and the consequences of her own choices. The novel explores creativity, vulnerability, ambition, and the risk of letting people truly know you, all filtered through a sharp, self-aware narrative voice.

Summary

MC, a 26-year-old freelance writer living in Brooklyn, is summoned by her best friend Joe to the offices of Jawbreaker, the media company where he works. When she arrives, she learns the reason for Joe’s panic: a hit romance novel titled Girl Next Door has become a cultural sensation, and the book is unmistakably about MC’s senior year of high school.

Joe reveals that the mysterious author S. K.

Smith is actually Nora Pike, the aloof neighbor with whom MC once shared a school literary-magazine staff but never formed a real friendship. In the novel, however, Nora has recast them as star-crossed teens whose paths reconnect a decade later.

Joe is desperate to run an exposé to save his job, but MC refuses to expose Nora. She eventually agrees only to visit her in person to understand what happened.

Back home, MC’s roommates are obsessed with the book, which deepens her dread. Joe forces the issue by contacting her brother Conrad behind her back and arranging for MC to stay with him and his wife Gabby in their Long Island hometown.

When MC arrives, she discovers Conrad has convinced their former teacher Ms. Kim to recruit her to help run a session of Explorations, their old school literary magazine.

Feeling cornered, MC agrees.

She heads to the public library, hoping to find Nora at work. Nora barely acknowledges her, and MC concludes the entire trip is pointless.

But Joe insists Nora is overwhelmed. The next day MC tries again, lingering at the library until she can approach her.

Nora remains distant until a staffer complains that the Winnie-the-Pooh performer for story hour is missing. MC volunteers on impulse.

Nora is surprised, and the moment opens the door between them just a crack.

Over the next days, MC helps with Explorations, reconnects with classmates, and spends awkward, charged moments with Nora. A storm forces Nora to offer MC a ride home, and their banter unexpectedly warms.

The story-hour fiasco brings them even closer when MC nearly faints inside the stifling costume and Nora rushes to help her.

Back in Brooklyn, Joe pressures MC about writing an article on Nora. His job is at risk, and MC reluctantly agrees to return home next month to gather more material.

Six weeks later, MC invites Nora to assist with another meeting of Explorations. Nora at first claims she is too busy, but circumstances drag her into attending.

Their simmering tension builds during a discussion about their high-school past, ending in an almost-kiss interrupted by Conrad. Later, Nora sends MC a teasing text ending in an XO, which sends MC into hopeful confusion.

During MC’s birthday weekend, Gabby pushes Nora and MC together at Fall Fest. They go to dinner, talk about their teenage identities, and begin acknowledging the attraction between them.

Soon afterward, MC and Nora finally sleep together, though MC is still hiding both the truth about the novel’s authorship and the real reason she has returned home. Nora believes their connection is mostly physical, while MC is overwhelmed by feelings she cannot yet articulate.

Back in New York, MC throws herself into writing an article not as an exposé but as an essay about being turned into fiction. She anonymizes details, hoping to protect Nora.

Joe loves the piece and submits it. MC agrees to run one final Explorations meeting before Christmas.

While in town, she learns Conrad has been hiding an affair and pushes him to tell Gabby. In turn, he insists MC must tell Nora about the article.

At the library holiday party, MC plans to confess everything, but a crisis pulls her away: Gabby discovers Conrad’s infidelity and disappears into the snowy night. MC leaves Nora waiting with a wrapped gift.

She spends Christmas Eve searching for Gabby with Conrad. In the car, she opens Nora’s gift: a signed copy of Girl Next Door and a note explaining why she wrote it in the first place.

The next morning, Nora confronts her. The article has gone live early, and small details have allowed fans to identify Nora.

Online harassment has erupted. Nora, furious and hurt, accuses MC of betraying her and storms away.

Gabby confronts MC as well. Conrad, devastated, loses trust in MC.

Alone, MC finds a new bike in the garage, a gift from all three of them, and breaks down.

Back in Brooklyn, MC isolates herself. Joe arrives to insist the article helped more than it harmed, but MC discovers at a New Year’s party that Seth, the magazine’s founder, added revealing details without her consent.

Feeling betrayed, she ends her friendship with Joe. Unable to cope, she returns to Green Hills, drifting through winter while Conrad works to repair his relationship with Gabby.

A chance encounter with Gabby in the grocery store finally brings honesty and healing. Afterward, MC takes a small, brave step toward Nora—shouting a random historical fact toward their old shared fence.

Nora briefly responds, with exasperation but also familiarity, leaving MC with a fragile sense of hope.

Time passes. MC and Nora begin texting again as Nora prepares to move out of state.

One day MC returns to the school and discovers Nora speaking to the Explorations students as a guest author. A friendly evening at the Horny Ram bar with friends follows.

Their chemistry flares again, and a playful arm-wrestling contest leads to renewed closeness, though Nora pulls away afterward.

MC’s life begins to steady: she pitches an internship program for her students and reconciles with Joe. Then Nora invites her to a Matrix movie marathon, which becomes an intense night of physical intimacy and emotional confession.

Nora admits she’s afraid MC only noticed her because of the book. MC reassures her that the book simply illuminated what was already there.

As Nora prepares to move to LA for the film adaptation of Girl Next Door, MC stages a surprise: she recreates the awkward high-school dance Nora once secretly adored. This becomes their private goodbye, though neither wants it to be permanent.

Weeks later, at the Explorations spring reading, Nora returns unexpectedly and reads aloud a poem MC once wrote about her as a teen. The gesture is a public declaration that she chooses MC now, not as a character, but as a real person.

They talk quietly in the hall afterward, acknowledging their mistakes and fears. Nora reveals she has left LA and wants to stay.

MC, about to begin a teaching program, wants the same. They move together into the next chapter of their lives with open eyes, finally ready to choose each other without hiding, without distance, and without fiction standing in the way.

Characters

MC

MC is a 26-year-old freelance writer who begins the story in emotional free fall: freshly heartbroken, creatively stalled, and convinced that her life is small and unremarkable. Her first instinct when distressed is to retreat into familiar fiction, and that habit sets up the central conflict of Girl Next Door: she suddenly realizes she has been turned into someone else’s fictional character without consent.

A core part of MC’s character is this tension between wanting to observe life from a safe distance and being forced, painfully and messily, to participate in it. She’s self-deprecating, witty, and often uses sarcasm as a shield, but beneath that is a deep hunger to be seen and chosen for who she really is.

Her decision to help Joe with the Nora story, even after naming it as unethical, reveals her conflict-avoidant streak and the way she can be pushed into moral gray areas when someone she loves is in crisis.

Over the course of the novel, MC’s biggest arc is about responsibility: to her own desires, to the people she loves, and to the power of her writing. Initially, she frames herself as someone to whom things happen—her ex leaves, Joe’s job is at risk, Nora fictionalizes her, Conrad and Gabby’s lives implode around her—but slowly she’s forced to confront the harm she actively causes.

Writing the Jawbreaker piece about being fictionalized feels, in her head, like a clever, self-aware compromise; in practice, it becomes an act of betrayal that out Nora, devastates Gabby and Conrad, and blows up her own privacy. The fallout makes MC reexamine the way she uses narrative to avoid direct conversations and truth-telling.

Her growth shows when she starts having harder, more honest talks—confessing her role in the article, owning her high-school crush on Gabby, and openly telling Nora what she feels instead of hiding behind cleverness.

MC’s queerness is tightly tied to shame and delayed self-knowledge. In high school, her crush on Gabby is buried beneath fear and confusion, and even as an adult she is still half-convinced that wanting too much will make people leave.

Nora’s book forces her to confront a version of herself that is both romanticized and recognizably her, pushing her to ask who she might have been if she’d been braver earlier. Her dynamic with Nora is a mix of intense chemistry, intellectual kinship, and constant miscommunication.

MC is more willing to move toward emotional commitment, but she is also the one who betrays Nora through the article, which complicates any simple “romantic heroine” reading. By the end, MC is still flawed and anxious, but she has reclaimed authorship of her own story: she chooses to stay rooted in Green Hills, commits to a teaching program, builds back relationships with Conrad and Gabby, and meets Nora as an equal, not as someone whose life is defined by what others write about her.

Nora Pike

Nora Pike is a study in carefully controlled vulnerability. To most people in Green Hills, she is the aloof librarian who avoids emotional entanglements, lives with her parents, and radiates “don’t talk to me” energy.

Secretly, she is S. K. Smith, the author of Girl Next Door, the wildly popular rom-com rooted in her own long-standing, unspoken feelings for MC. Nora channels everything she cannot say out loud into fiction, rewriting an adolescence where she and MC get the romance they never had.

This act is simultaneously romantic, self-protective, and ethically fraught: she hides behind a pseudonym and a thin veil of fictionalization, assuming the book will stay small, private, and safely deniable. When it explodes into fame, her tendency to disappear instead of confront is brutally exposed.

Emotionally, Nora is terrified of being abandoned and of being the one who ruins other people’s lives by wanting too much. That fear manifests as distance, sarcasm, and a habit of preemptively cutting ties—something Jen warns MC about when she says Nora drops people without explanation.

Nora’s relationship with MC oscillates between intense physical closeness and abrupt withdrawal, driven by her belief that allowing herself full emotional engagement will end badly for both of them. She genuinely cares for people—she’s tender with kids at story hour, protective of Lois and Maureen, and ultimately generous in how she credits MC and Joe for her success with the students—but prefers to express that care through acts of service rather than direct confession.

The bird-clock moment, where she is startled into laughter and finally kisses MC, captures her: intensity undercut by absurdity, emotion that leaks out when her careful control is disrupted.

Nora’s arc is about stepping out from behind fiction and choosing real, messy connection. Being outed by MC’s article is a violation, but it also forces her to confront what it means to be publicly known as a writer and as a queer woman.

She takes the film opportunity, moves to LA, and discovers that external success does not fix her fear or isolation. When she returns to Green Hills, miserable from script work and advisory duties, she finally does the thing she’s avoided all along: speaks directly to MC, in public, about love and desire by reading MC’s own poem aloud.

In that moment, she reverses their pattern. Instead of hiding behind a book or a pseudonym, she uses MC’s words to expose her own feelings, in front of their community, and chooses to stay.

Her willingness to say she doesn’t want to be apart anymore, even as she remains prickly and awkward, marks her growth from the girl who could only love MC safely on the page to a woman ready to risk loving her in real life.

Joe

Joe is MC’s best friend, a Jawbreaker editor whose charm, ambition, and panic about job security drive much of the plot. At his best, Joe is loyal, funny, and genuinely invested in storytelling as a way to elevate underdog narratives.

He helps MC with her work, shows up at her apartment with breakfast and yearbooks, and gamely reenacts their old interpretive dance without ego, just to give Nora and MC a meaningful goodbye. At his worst, he’s a cautionary tale about what happens when professional desperation combines with the digital media attention economy.

He sincerely believes that unmasking Nora could save his job and his section, and that belief lets him rationalize pushing MC into ethically dubious territory.

Joe’s flaw is his comfort with treating other people’s lives as content. He talks about “angles” and “contradictions” like a good editor, but he fails to account for how those angles land on real people.

By feeding Seth details like their graduation year and not insisting on seeing the final edits, he becomes complicit in the article’s most damaging betrayals. When confronted, he initially tries to minimize the harm—pointing to police reassurances and Nora’s rising sales as evidence that “no one is unsafe.” It’s only later, on the Jawbreaker rooftop and beyond, that he fully acknowledges he sold out his own values and MC’s trust.

Joe’s arc is quieter than MC’s or Nora’s, but important. He moves from being a company man desperate for Seth’s approval to someone actively seeking a way out of that environment.

He apologizes to MC not only for what happened with the article but for allowing himself to be reshaped by an egomaniacal boss. His later support—charming the students, promising to help with the school magazine, and collaborating on MC’s “parting gesture” dance—shows a return to the version of Joe who loves stories for their emotional truth rather than just their traffic potential.

By the end, Joe becomes the friend who still makes mistakes, still craves career success, but is consciously trying to be the kind of writer and editor who doesn’t destroy people to get there.

Conrad

Conrad, MC’s older brother, represents both a source of childhood safety and a mirror for her avoidance. As a high school administrator and expectant father, he’s outwardly the responsible sibling, the one who stayed in Green Hills and built a life.

Underneath, however, he is haunted by a sense of failure—dropping out of Harvard, returning home, and quietly believing he has disappointed everyone. That shame contributes to his affair with Jae; they bond over shared failures, and Conrad slips into a betrayal that he then tries to minimize and bury.

His arc is about moving from silent guilt to active accountability.

Conrad’s relationship with MC is complicated by distance and old patterns: she assumes he doesn’t miss her; he actually does but doesn’t know how to say it. When MC returns, they fight, tease, and gradually re-establish a sibling intimacy built on more honesty.

Conrad pushes MC to admit that something deeper is going on than “research” for a supposed novel, and later she pushes him to confess his affair to Gabby. Their long car rides, ornament-smashing Christmas blowup, and slow truce while shoveling snow all show the Calloway tendency to avoid hard conversations until they explode.

Yet Conrad consistently shows up for MC—letting her move back home even when he’s furious, helping with her grad school applications, and trying to include her in his future by turning her old room into the nursery.

As a soon-to-be father, Conrad is paralyzed by the fear that his mistakes define him forever. He worries his child will hate him when they learn about his affair, equating moral failure with permanent unlovability.

MC and Linda’s advice—that everyone fails, that you don’t owe your child every sordid detail, and that you keep trying anyway—helps him shift from self-loathing toward responsibility. By the end, Conrad is still anxious and imperfect, but he is doing the work: writing daily apology letters to Gabby, carefully planning the nursery, and remaining emotionally available to MC.

He becomes a symbol of the book’s belief that family bonds can be damaged, tested, and still rebuilt through sustained effort.

Gabby

Gabby is both the golden girl of their high-school past and a fully realized adult woman grappling with marriage, pregnancy, and betrayal. In MC’s memory, Gabby is luminous—beautiful, confident, and the object of a closeted crush.

As an adult, she remains warm and charismatic, but the narrative allows her complexity: she can be controlling, defensive, and deeply frightened of losing her sense of self to motherhood. Her pregnancy isn’t framed as a purely joyous event: she jokes about missing her old life and worries about being reduced to a mom archetype, which humanizes her beyond MC’s teenage pedestal.

Gabby’s loyalty is fierce but not blind. She is thrilled at the possibility of MC and Nora getting together and actively meddles at Fall Fest to give them time alone, but when she discovers Conrad’s affair and MC’s complicity in the secrecy around it, her anger is volcanic.

Smashing ornaments on Christmas morning, she voices years of unspoken resentment and disappointment, and her decision to leave shows she will not silently absorb betrayal. Even then, Gabby’s later choices are nuanced: she reads both Girl Next Door and MC’s article, takes time and space, and ultimately agrees to speak to MC again after MC offers a sincere, thorough apology.

In the end, Gabby embodies forgiving without forgetting. She lets Conrad back into her orbit slowly, sets boundaries, and still chooses to invite MC back into her emotional life.

Her joking line about maybe making out with MC if she’d known about the crush back then doesn’t trivialize the hurt; it signals that she’s finally comfortable enough with herself and with MC’s sexuality to acknowledge the past without fear. Gabby’s journey reinforces the theme that love—romantic or familial—isn’t about perfect behavior; it’s about whether people can admit they were wrong and choose to move forward differently.

Ms. Kim

Ms. Kim is the teacher who quietly shapes both MC’s present and past.

As faculty advisor to the Explorations literary magazine, she helped teenage MC and Nora find a home for their creative impulses long before either of them understood what those impulses meant. In the present timeline, she appears as a steady, gently pushy adult who ropes MC into running meetings, praises her in front of the students, and subtly reminds her of her capabilities.

Ms. Kim sees MC not just as a former student but as a potential colleague—a writer and educator with something to offer the next generation.

Her decision to leave the principalship and return to classroom teaching mirrors MC’s arc in a softer, older key. Ms. Kim, too, chooses the intimacy of working with students and nurturing creativity over the abstraction and stress of administration. She represents a life path MC can recognize and aspire to: one where writing and teaching are not consolation prizes for failed ambitions but meaningful, deliberate choices.

Ms. Kim’s presence anchors the school scenes with a sense of continuity, showing how one adult’s belief in young people can echo forward into their adult lives.

Lois

Lois is one of Nora’s colleagues at the library and a kind of unofficial aunt figure to both Nora and MC. She’s brisk, practical, and hilariously commanding—she orders Nora to help with Explorations and pushes her toward the teens almost against her will.

Lois functions as a bridge between Nora’s closed-off interior life and the wider community. She sees Nora’s talent and emotional stuckness clearly and nudges her, with a mixture of bossiness and affection, toward greater visibility and engagement.

Her role is particularly important at the Christmas Eve party and the final reading. Lois helps orchestrate events: insisting Nora attend the holiday gathering, encouraging her to own her status as an author, and later hovering in the background filming Nora’s poem reading like a proud parent.

She represents the grounded adult world of Green Hills—the people who have watched MC and Nora grow up, who gossip and meddle but ultimately want the best for them. Lois’s unwavering presence and good humor help make the library and school feel like communal spaces rather than just backdrops to the romance.

Maureen

Maureen, another library colleague, brings a softer, more playful energy to the adult ensemble. She dances with MC at the Christmas party, participates in the small-town rituals, and is part of the quiet chorus of adults who are rooting for Nora and MC even if they don’t know the full stakes.

While her role is less central than Lois’s, Maureen embodies the affectionate, slightly nosy community that surrounds the protagonists. She doesn’t push as hard, but her warmth helps offset the harsher moments of public scrutiny and internet trolling, reminding us that not all attention is hostile.

Jen Turner

Jen Turner is a former star athlete turned gym teacher, and she initially appears in the story as the intimidating ex or maybe-current partner in Nora’s life. She has a reputation as a player, and her dynamic with Nora is prickly and unresolved—part resentment, part lingering connection.

Jen’s warnings to MC about Nora’s tendency to drop people without explanation contain genuine concern wrapped in spite; she is both bitter about being hurt and honest about patterns Nora hasn’t yet confronted.

Jen’s later interruption at the Horny Ram and her barbed comment about Nora’s “bestseller” reveal unresolved jealousy—not only of Nora’s success but of the intensity between Nora and MC. She functions as a foil: someone who has also been close to Nora but didn’t get a sustainable relationship out of it.

Jen’s presence underlines Nora’s history of emotional retreat, making it harder for MC to trust that things will be different for her. At the same time, Jen is never reduced to a simple villain; she’s another person trying and failing to protect herself in messy queer dynamics where everyone knows everyone else’s business.

Jae

Jae is Conrad’s colleague and affair partner, and the story is careful not to flatten them into a mere plot device. Jae and Conrad connect over shared feelings of failure, both feeling like they fell short academically or professionally.

Their affair grows out of that vulnerable space, making it more than just impulsive cheating; it’s also a misguided attempt to feel understood and chosen. Jae’s later insistence that Conrad take responsibility rather than simply “put it behind them” shows integrity and a refusal to collude in secrecy.

Jae’s presence exposes cracks in Conrad and Gabby’s relationship but also helps move Conrad toward accountability. Their interactions complicate any simplistic moral judgment: Jae participates in something hurtful but also demands honesty and growth.

They embody the novel’s theme that adults can do wrong for understandable reasons and still be called to act better afterward.

Heather

Heather is one of the Explorations students and a symbolic bridge between generations of writers. Her anonymous experimental poem sparks a debate about anonymity, fear, and accountability—questions that resonate directly with Nora’s use of a pseudonym and MC’s article about being fictionalized.

In that sense, Heather’s work acts as a thematic mirror, allowing MC to process, with the students, issues she has not yet sorted out in her own life.

Later, Heather produces an old copy of the Explorations magazine at the reading night, physically linking MC’s and Nora’s teenage writing to the current generation. Her decision to orchestrate one last surprise reader—Nora—demonstrates both a sense of showmanship and an instinct for emotional theater.

Heather is the kind of student Ms. Kim and MC work for: sharp, observant, and capable of making connections between art and life that the adults themselves are still struggling to manage.

Ben

Ben is another Explorations student, introduced as friendly and open during MC’s first tentative return to the classroom. His comedic “Bathroom Bard” poem at the final reading night brings the house down, showing the confidence and playfulness that MC hopes to cultivate in her students.

Ben’s presence helps MC see that the magazine is not just a relic of her past but a living, evolving community that can exist without her, even as she becomes an important mentor.

For MC, Ben and the other students are proof that she can step into a role beyond “failed freelancer” or “accidental muse”: she can be the kind of adult who shapes young writers the way Ms. Kim once shaped her.

Ben’s success onstage makes MC proud, and that pride is part of what anchors her decision to stay, teach, and invest in Green Hills rather than chasing a more glamorous but less emotionally meaningful life.

Seth Flanagan

Seth Flanagan, founder of Jawbreaker, embodies the worst impulses of digital media culture. He is smooth, self-satisfied, and utterly comfortable treating people’s private pain as entertainment.

His bragging at the New Year’s party about slipping in “class year” details as a “little bone” for superfans is chilling precisely because he is so casual about the harm it might cause. Seth views MC’s article not as a reckoning with ethical boundaries but as a traffic win and a career boost, and he is entirely uninterested in the human beings at the center of it.

Seth’s influence over Joe dramatizes how ambitious, idealistic media workers can get twisted by toxic mentorship structures. Joe’s desire for Seth’s approval leads him to compromise both MC’s conditions and his own prior ethics.

Seth never has a redemption arc; instead, he remains a symbol of an industry that rewards boundary-pushing and punishes nuance. His presence pushes MC to reclaim her sense of integrity and pushes Joe to leave Jawbreaker and imagine a different version of his career.

Linda

Linda, MC and Conrad’s mother, carries her own history of mistakes and regret. Her affair with Gregor and the divorce that followed are sources of lasting guilt; she worries constantly about having damaged her children’s capacity for stable love.

When she learns about Conrad and Gabby living apart, she reacts with panic and overreach, wanting to swoop in and fix everything, yet her impulse to ambush Conrad reflects the same avoidance of direct, gentle communication that plagues the whole family.

Despite her flaws, Linda offers a different, older perspective on failure. Her blunt statement that everyone does things they’re ashamed of—but that life goes on and love can survive—helps both MC and Conrad contextualize their own mistakes.

Linda’s conversation with MC about her love life, and MC’s halting admission that she is seeing someone she might someday introduce, marks a step forward in their relationship: they are starting to talk about queerness and intimacy without either silence or melodrama. Linda’s arc is less about change and more about revelation—MC finally sees her not just as a parent who messed up but as a person who is still trying, which mirrors MC’s own journey toward self-forgiveness.

Lauren Horowitz

Lauren Horowitz, S. K.

Smith’s editor, enters the story as a professional caught in the storm of the Jawbreaker article. She is furious with MC—for understandable business and ethical reasons—but also recognizes that the article has boosted Nora’s sales.

Lauren stands at the intersection of art and commerce, forced to navigate what happens when private damage leads to public success. She represents the wider literary world’s complicity: publishers are happy to profit from a narrative built on blurred boundaries as long as it sells.

Her confrontation with MC highlights how even well-intentioned pieces about exploitation can become part of the same machinery they critique. Lauren doesn’t offer moral comfort or a neat solution; her presence reminds us that in publishing, ethical questions rarely align cleanly with financial outcomes.

Her frustration is part self-protection, part genuine concern for her author, and she adds texture to the book’s exploration of who benefits when someone’s life becomes a story.

Nico

Nico appears later as Joe’s hookup and a small but telling part of Joe’s emotional evolution. Joe’s flirty selfie from Nico marks a shift from his earlier, somewhat chaotic romantic life toward something slightly more grounded, even if still casual.

Nico’s presence allows MC to tease Joe and see him as a person trying to build relationships outside of work, not just a co-conspirator in professional disasters. Although Nico doesn’t play a major narrative role, their existence contributes to the sense that life for these characters continues beyond the central romance, with new connections and possibilities forming off to the side.

Patrick

Patrick is one of the students involved in assembling the magazine, and Nora gravitates toward helping him edit at Heather’s farmhouse. Their collaboration suggests Nora’s latent talent as a teacher and mentor, a role she initially resists.

Patrick’s need for editorial guidance and Nora’s instinctive ability to provide it show another way she can exist in the world beyond solitary writing and panic-induced withdrawal. Patrick, like Ben and Heather, helps anchor the future of Explorations and offers Nora a glimpse of a life where she is not just an anxious, overwhelmed author but someone who can guide younger creatives.

Helen

Helen, one of the older women hovering at the back of the final reading alongside Lois and Maureen, is part of the chorus of local adults bearing witness. She may not have a lot of lines, but her presence contributes to the sense that the whole town is, in some way, watching this story unfold.

Helen and the others filming Nora’s performance on their phones symbolize how even intimate, vulnerable moments now exist under the gaze of social media and community documentation. They’re not malicious; they’re just part of the new ecosystem in which Nora and MC must navigate being both private people and semi-public figures.

Gregor

Gregor, Linda’s former affair partner, never appears directly, but his impact ripples through the family. He stands in for the disruptive force that shattered the Calloways’ previous sense of security.

For MC and Conrad, Gregor’s existence has long been less about him as a person and more about what he represents: proof that parents can be flawed, selfish, and capable of breaking vows. Linda’s continued guilt over her relationship with Gregor shapes how she advises her children about their own mistakes, and her experience becomes a cautionary template that, ironically, helps them contextualize their own missteps.

Gregor remains a background figure, but his shadow emphasizes that betrayal and forgiveness are generational patterns, not isolated incidents.

Fuzzbox

Fuzzbox, Nora’s cat, is more than a cute detail; the logistics of moving Fuzzbox become a shorthand for Nora’s anxiety about change and responsibility. Her late-night texts to MC about transporting the cat reveal how much she trusts MC with her worries, even when she struggles to articulate deeper fears.

Fuzzbox represents the domestic, tender side of Nora’s life—the part that isn’t glamorous or literary, just ordinary and vulnerable. The cat’s presence in Nora’s move discussions underscores how any relocation for Nora isn’t just a glamorous career step; it’s a disruptive, stressful leap that affects the small creature she cares for and, by extension, the emotional home she’s built in Green Hills.

Themes

Authorship, Narrative Ownership, and Being Turned into a Character

Authorship in Girl Next Door is treated as both a creative gift and a profoundly invasive act. From the opening revelation that Nora has written a bestselling rom-com based on MC’s life, the story keeps asking who gets to tell a story and what it costs the person being written about.

Nora has transformed their shared past into a marketable narrative, turning a half-ignored neighbor and quiet literary-mag colleague into the heroine of a sweeping love story. For MC, that choice is not flattering; it feels like a theft of agency.

She never agreed to be turned into “Nicole,” the character whose emotions and memories have been reconstructed and exaggerated for public consumption. The book tracks not only her anger at that appropriation, but also her recognition that she has done something similar by agreeing to write the Jawbreaker article about Nora.

She tries to comfort herself by using pseudonyms and altering details, yet the fandom easily reverse-engineers the truth, proving that “thinly veiled fiction” offers little protection in a digital culture obsessed with clues and Easter eggs. Authorship becomes a kind of power, and the novel shows how seductive it is to believe that shaping a story is the same as understanding a person.

Nora believes she can fix her feelings and her past by crafting them into a rom-com; MC believes she can process her hurt by turning Nora into a subject, something to be examined. Both discover that writing about someone is not neutral: it changes relationships, exposes vulnerabilities, and can harm people who never chose to be part of the narrative.

By the end, the book does not reject authorship, but it suggests that ethical storytelling requires consent, accountability, and a willingness to risk real conversation instead of hiding behind pages and articles.

Queer Desire, Self-Discovery, and Late Coming-Out

Queer desire in Girl Next Door is messy, delayed, and layered with self-misreading. MC’s sexuality does not arrive as a single defining moment; it emerges in fragments: her teenage crush on Gabby that she never voiced, the confused intensity of her attention to Nora, the awkward interpretive dance that exposes more than she understands at the time.

The novel shows how easily young queer feelings get misfiled as admiration, envy, or “just friendship” when no one gives them language. Years later, MC is in Brooklyn, supposedly a grown woman, but she is still untangling what she wanted back in high school and what she wants now.

Nora, meanwhile, channels her longing into fiction, writing the love story she never had the courage to pursue in real life. Their adult relationship is marked by false starts and emotional dodges: charged car rides, almost-kisses in classrooms, sex that feels huge but is followed by silence or retreat.

The Matrix marathon and the explicit, almost shocking sexual intimacy in the dark theater stands next to Nora’s refusal to call what they have a relationship, which exposes how desire alone does not solve fear or shame. MC’s queerness is also entwined with her family history and friendships: when Nora blurts out her old crush on Gabby, it detonates years of secrets and forces MC to reckon with the fact that hiding her feelings has shaped every bond she has.

Yet the book treats queerness as more than pain; it turns toward joy in scenes like the Explorations readings, where young writers share work without apology, or in the final confession via MC’s old poem performed by Nora. By the ending, queer love is not a scandal or a hidden subtext but something named in front of a crowd, claimed by two adults who have learned that they are allowed to want each other openly and to build a life that reflects that desire.

Privacy, Exposure, and the Violence of Going Viral

Privacy in Girl Next Door is fragile, easily punctured by the machinery of media and fandom. MC’s first encounter with the book is not a quiet, personal reading; it arrives through Jawbreaker, a digital outlet hungry for content, eager to capitalize on the mystery of S.

K. Smith.

Nora’s pseudonym and small-town anonymity crumble the moment Jawbreaker’s article goes online with a few extra specifics added for “spice. ” The book shows in granular detail how quickly online communities can identify real people from supposedly anonymized details, and how that process strips those people of control over their own narratives.

Nora’s harassment by trolls, the invasive speculation about her sexuality, personality, and mental health, and the way local life in Green Hills becomes a backdrop for internet drama all underline how public attention can feel like an assault rather than a victory. MC’s panic when notifications flood her phone and her instinct to delete apps and block Joe reveal the psychological cost of exposure, even when that exposure is framed as career advancement or literary buzz.

At the same time, the story is honest about the ambivalence: the article boosts sales, strengthens Nora’s profile, and keeps Jawbreaker afloat. This complicates easy moral judgments; exposure is not purely evil, but it is unpredictable and rarely under the control of the people most affected.

The book asks what it means to be a “subject” in this environment: can anyone be written about without becoming fodder for commentary and speculation? In the end, the contrast between the chaotic online response and the intimate, small-scale acts of coming forward—like Nora reading MC’s old poem to a room of students and friends—suggests that the only sustainable way to share oneself is in spaces where consent, context, and care matter more than clicks.

Home, Return, and Rewriting the Past

Home in Girl Next Door is not a stable comfort zone; it is a site of unfinished business that MC has spent years avoiding. Green Hills represents teenage humiliation, unresolved crushes, her father’s death, and the sense that life happens elsewhere, in places like Brooklyn.

Her return is not voluntary in the emotional sense; it is framed as a reconnaissance mission for Joe and Jawbreaker. Yet the longer she stays, the more the town forces her to confront who she was and who she has become.

Walking the halls of Green Hills High as an adult, running the Explorations meeting, and seeing her younger self reflected in students like Ben and Heather push her to reassess what she once dismissed as a dead end.

The town is not frozen; people have grown older, taken on new roles, and revealed unexpected sides of themselves: Gabby is both the luminous crush of the past and a stressed, pregnant woman bracing for single parenthood; Ms. Kim is now a principal who will eventually choose to return to classroom teaching; Nora is the quiet neighbor turned bestselling writer. The novel refuses the usual dichotomy of hometown as either suffocating trap or sentimental paradise.

Instead, it shows how going back can expose illusions on both sides. MC discovers that she has exaggerated her isolation in high school; the new bike in the garage proves her family and neighbors once noticed her in ways she never allowed herself to see.

At the same time, she discovers that leaving did not magically solve her fear of commitment or her career uncertainty. By the final chapters, home has become less a static place and more a living network of relationships that she can participate in as an adult—teaching in Queens while still sleeping at Conrad’s, going to readings, and attending local events.

The past cannot be undone, but it can be rewritten through new choices, apologies, and shared rituals, turning Green Hills from a place she escaped into a place she consciously inhabits.

Family, Inheritance, and Imperfect Care

Family relationships in Girl Next Door highlight the ways love is often clumsy, misdirected, and burdened with old guilt. Conrad and MC’s sibling bond carries the residue of their father’s death and their mother’s affair.

Both grew up learning that adults can betray each other and then try, imperfectly, to patch things together. Conrad’s cheating with Jae while Gabby is pregnant is not excused by his backstory, but it is framed within his deep insecurity about failing at Harvard and his fear of not being able to live up to the role of responsible father and husband.

MC becomes both judge and accomplice: she pushes him toward honesty while hiding her own secret project about Nora, repeating the very patterns of concealment she resents in others. Their later work together on the nursery, the daily apology letters Conrad sends Gabby, and MC’s constant presence in the house depict family not as a place where everyone behaves well, but as a field where people keep trying even after they have done serious damage.

Their mother, Linda, adds another layer: her confession of her own affair and guilt shows how hurt travels between generations. Yet the book resists despair; Linda’s blunt advice to Conrad—that everyone will hurt someone, and the point is to keep showing up anyway—becomes a rough guiding principle for both siblings.

Even Gabby, who has every reason to leave for good, chooses to engage, confront, and eventually seek some form of reconciliation, especially because of the baby. MC’s own sense of family widens to include the surrogate kin of teachers, students, and even Nora’s chaotic household.

In the end, inheritance is not just genetic or material; it is the set of stories and habits around love and apology that each person decides to repeat or revise. MC and Conrad’s shared work to support each other, despite mutual anger, signals a move toward a more honest, less idealized idea of family: one where people are allowed to be wrong, but not allowed to stop caring.

Friendship, Loyalty, and Betrayal

Friendship in Girl Next Door is tested far more harshly than many romantic relationships. MC and Joe begin as the archetypal best friends: he is the anxious, ambitious editor, she is the somewhat directionless writer, and their banter is easy and affectionate.

But the crisis over Nora’s identity pulls hidden tensions to the surface. Joe frames the potential article as a career lifeline, using MC’s empathy to enlist her in a project that is, at its core, exploitative.

MC agrees because she wants to help him, convincing herself they can do it ethically by changing names and keeping certain details secret. The betrayal comes not only from the article’s fallout, but from Joe’s willingness to hand Seth Flanagan the small identifying details MC had insisted on protecting.

The rooftop confrontation at the New Year’s party makes clear that loyalty can be eroded not by cartoon villainy, but by ordinary professional desperation and a desire for approval from powerful people. Yet the novel refuses to abandon Joe to the role of villain.

He apologizes, looks for another job, helps with MC’s plan for the students, and shows up for Explorations and the magazine assembly not for career benefit, but because he cares. By the end, their friendship has been stripped of illusion: MC knows Joe is capable of selfish choices, and Joe knows MC will not quietly accept being used.

That knowledge actually grounds them better than their early, more idealized bond. Other friendships orbit this central one: Gabby as both friend and unresolved crush; the uneasy camaraderie among staff at Jawbreaker; the emerging bond between MC and her students.

Through all of these, the book emphasizes that loyalty is not a static trait; it is a series of decisions to listen, to admit wrong, to defend someone in public, and sometimes to walk away when a friend has become an extension of someone else’s power. When MC and Joe stand in the high school auditorium, reenacting their old dance for Nora, their friendship is no longer about aspiring media cool, but about mutual willingness to look ridiculous for the sake of someone they both care about.

Fear, Vulnerability, and the Risk of Real Intimacy

Fear of genuine intimacy shapes almost every choice Nora and MC make in Girl Next Door. Nora builds her life around controlled roles: quiet librarian, dutiful daughter in the cluttered family house, anonymous author behind a pseudonym.

She pours her feelings into a book where she can script outcomes and edit scenes, but she cannot bring herself to say “I like you” to the real woman who lives next door. MC, in turn, uses self-deprecating humor, irony, and constant movement between places as armor.

She goes to Green Hills for “work,” sleeps with Nora while still hiding the article, and repeatedly tries to process her emotions through writing instead of direct conversation. The result is a series of emotional near-misses: an almost-kiss after a layout lesson, sex that feels monumental but is followed by Nora insisting they owe each other nothing, an arm-wrestling bet that masks a plea not to be abandoned.

The book shows how intimacy is not just about physical closeness but about exposure to disappointment, rejection, and change. Nora fears that MC’s interest is a byproduct of the novel, something she “manifested” rather than something real, and that fear makes every good moment feel temporary.

MC fears that if she speaks plainly about what she wants, she will lose not only Nora but also the fragile sense of self she has built since her last breakup. The turning point arrives not in a grand romantic gesture, but in a series of smaller acts of emotional honesty: MC confessing the article to Conrad and then to Nora, Gabby and MC speaking frankly in the grocery store, Nora admitting that LA and her screenwriting work have made her miserable.

The final scene at the Explorations reading, where Nora reads MC’s old poem aloud, enacts a different kind of risk: speaking desire openly, in public, without a pseudonym or a genre shield. By choosing each other after that, as adults who understand how easily things can go wrong, they show that intimacy is not the absence of fear but the decision to move forward despite it.

Art, Teaching, and Making Space for Young Voices

The recurring presence of the Explorations literary magazine and the high school itself turns Girl Next Door into a story about art as a communal practice, not just a private refuge. MC begins her return to Green Hills feeling like an imposter, convinced she is a failed writer whose life consists of odd freelance gigs and a messy personal history.

Being asked to run Explorations is initially humiliating; it reminds her of ambitions she believes she abandoned. Yet the meetings with students, the rhyming introductions, the arguments over anonymous submissions, and the final reading night under string lights give her a new frame for what writing can be.

It is not only about producing a polished novel or viral article; it is about giving young people a place to test voices, to write politically wild turkey-vulture stories, to pen experimental anonymous poems, and to perform bathroom-themed comedy that brings the house down. Nora’s shift from reluctant participant to active mentor is equally important.

She starts as the aloof, reluctant guest and ends as a featured author who credits MC and Joe for pushing her into visibility, even as she critiques the way that visibility unfolded.

Teaching, in this world, becomes a form of repair: for MC, it is a way to do better than she did when she failed to defend Nora as a teen; for Ms. Kim, it is a calling strong enough to draw her away from administration back into the classroom.

The presence of Jawbreaker’s potential internship program for the students links their small-town efforts to a wider media landscape, but the book is clear that the most meaningful artistic moments happen in rooms without cameras: a quiet library where Nora reads to children, an auditorium where an old interpretive dance is resurrected, a commons area where a decades-old poem is finally heard by the person it was written for.

Through these scenes, the novel suggests that art and teaching matter because they create structured, caring spaces where people can speak truths they are not yet brave enough to live, until, eventually, those truths begin to reshape their actual lives.