Gliff by Ali Smith Summary, Characters and Themes

Gliff by Ali Smith is a novel that explores the boundaries of identity, memory, and the fluidity of time. Through the eyes of two sisters, the story invites readers into a world where the conventional markers of reality, such as names, places, and history, become ever-shifting.

At the heart of this tale is the notion of impermanence, the search for meaning in a world increasingly defined by surveillance and corporate manipulation. As the characters struggle with their own existence in a society that demands categorization, they face the complex interplay between personal freedom and the oppressive forces of control. Smith’s storytelling captures a tension between the tangible and the abstract, questioning the essence of what it means to belong and to be seen.

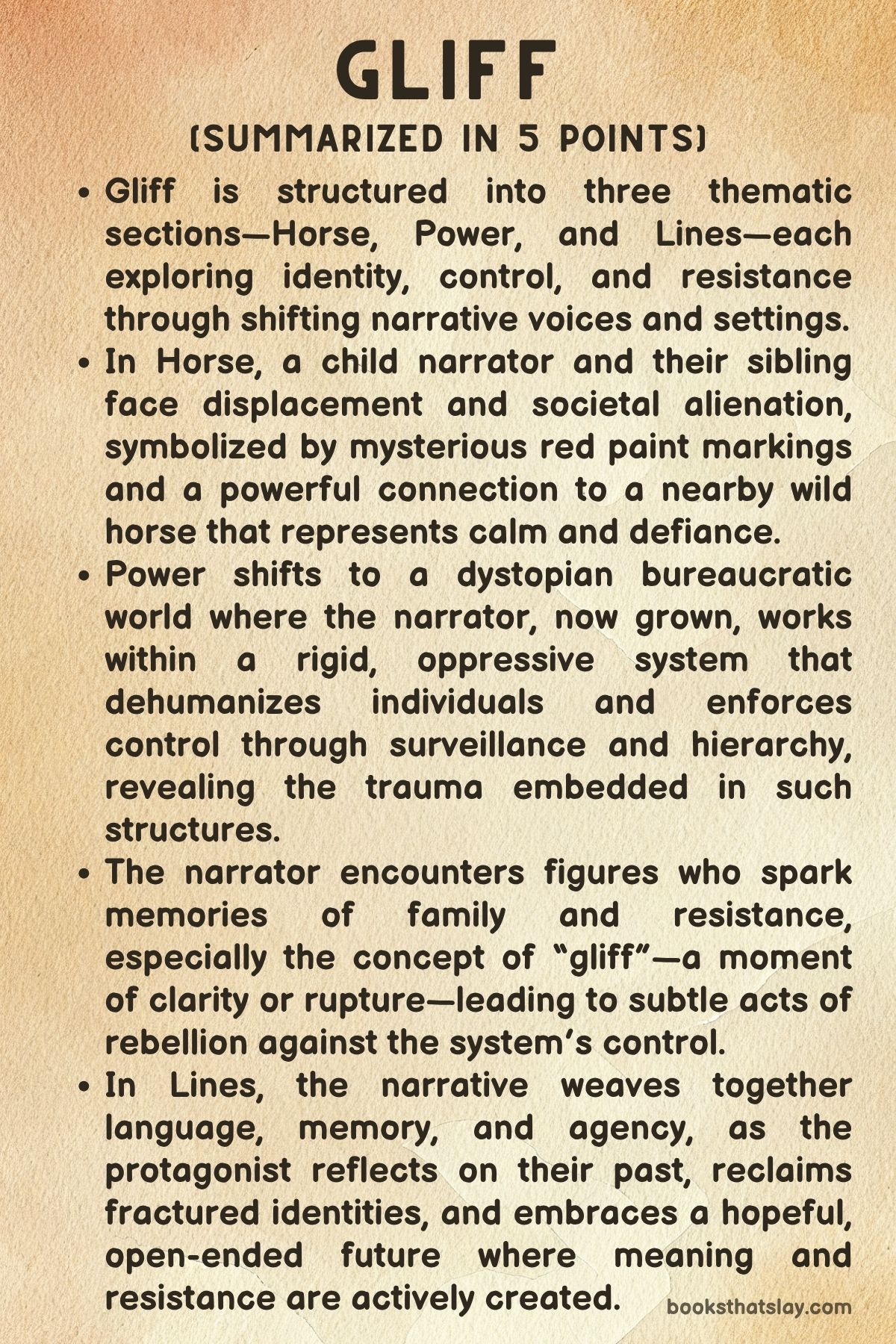

Summary

Gliff follows the lives of two sisters, Bri and her younger sibling, as they navigate a world marked by uncertainty, loss, and an evolving understanding of self. The novel begins with the introduction of the sisters’ relationship with their mother, who works at a hotel.

The mother appears distant, emotionally withdrawn, and altered by the rigid structure of her uniform and job. There is a sense of estrangement between the mother and her children, amplified by her refusal to discuss her health openly.

This sense of abandonment seems to pervade the family’s dynamic, leaving the children feeling adrift, unable to truly connect with the woman who once represented their home.

Leif, the older sibling, takes on the role of caretaker, attempting to hold the family together despite their fractured relationship. His emotional distance is mirrored in the siblings’ lives as they face the disorienting reality of their home.

Upon returning to their house, they find strange red lines painted around it—lines that seem to symbolize a boundary or restriction. This marking of their home conveys a sense of impermanence, suggesting that the space they once called home is now subject to the whims of forces beyond their control.

The house feels hollow and unfamiliar, stripped of the warmth it once held.

The children’s experience in their new space is characterized by a lack of stability. They try to adjust, but the idea of permanence is foreign to them.

Their home feels like a shell, a temporary abode rather than a lasting refuge. This feeling of impermanence, of being in constant transition, hangs over their existence.

Leif’s decision to distance himself from his family underscores the underlying tension: he believes that by separating himself from them, he is offering them a better future. However, this decision is complicated by his emotional detachment and the sense that the family, in its entirety, is something he can no longer carry.

The children continue to struggle with their shifting boundaries, both physical and emotional. They ration their food, cling to old traditions, and talk about their mother’s songs in an effort to maintain a semblance of normalcy, even as their world feels increasingly unmoored.

These attempts at creating stability in the face of an indifferent world serve as an ongoing reminder of the emotional and psychological toll of living in such a transient state. Their relationship with technology, too, is fraught with tension.

The children are caught between the old world their mother clings to—one where modern conveniences, like smartphones, are rejected—and the new world they are expected to embrace, a world increasingly dominated by surveillance, corporate interests, and impersonal forces.

The narrative also introduces the concept of “unverifiables,” those individuals and situations that exist outside the realm of official documentation or societal acknowledgment. This theme is explored through the sisters’ interactions with characters like Colon, a socially awkward figure obsessed with data and categorization.

Colon’s obsession with collecting information contrasts with the narrator’s desire for freedom and individuality, highlighting the tension between the need for control and the pursuit of personal autonomy. The idea of categorization becomes a broader critique of a society that values verifiability over authenticity, where individuals are stripped of their true selves in favor of easily quantifiable identities.

In addition to these societal themes, the novel focuses on the significance of names and identity. The act of renaming the horse “Gliff” symbolizes the fluidity of identity, the rejection of fixed labels, and the power dynamics inherent in the act of naming.

Bri’s sister’s fluid approach to her own name serves as a personal rejection of societal expectations, embracing an ever-changing self that defies the rigid structures imposed by the world around her. This dynamic explores the arbitrariness of labels and the ways in which individuals assert their autonomy by challenging the very systems that seek to define them.

The narrative also delves into the story of Saccobanda, an enigmatic figure whose removal from society sparks a larger rebellion from the natural world. Saccobanda’s transformation of her environment—from stones to rivers—imbues everything around her with a sense of belonging and meaning.

Her removal, deemed “unverifiable,” prompts a revolt not only from the people but from nature itself, symbolizing the resistance to the dehumanizing forces that seek to control and categorize the world. This revolt grows into a massive force, symbolizing the voices of the oppressed and marginalized who demand recognition and justice.

In a parallel storyline, Bri and her sister’s journey leads them to encounter individuals who, like them, exist outside the system of verification. These encounters with others who are unverified reveal the vulnerability that comes with living outside the boundaries of societal norms, as well as the possibility of freedom.

Bri’s exploration of language and her desire to understand the connection between words and reality drives her to deeper insights about the ways in which language both connects and controls. Through her interactions with Oona, an elder who teaches her about language, Bri begins to understand the complexities of how words shape our perception of the world and our place within it.

Ultimately, the story of Bri and her sister is a journey of survival and self-discovery in a world that increasingly prioritizes control and categorization. Their struggle to maintain their sense of self in the face of a society that seeks to erase or redefine them reflects broader themes of identity, freedom, and the search for meaning.

The siblings’ quest is not only about navigating the oppressive forces around them but also about reclaiming the power to define themselves in a world that tries to define them for them.

Characters

The Mother

In Gliff by Ali Smith, the mother plays a pivotal yet emotionally detached role. When first introduced, she is depicted as a distant figure who seems to have undergone a transformation, both physically and emotionally, due to her uniform and the apparent emotional distance she maintains from her children.

Her role is not merely as a caretaker but as a symbol of disconnection, as she is described as “smaller” and almost unrecognizable. Her stoic demeanor when questioned about her health points to an underlying tension in her relationship with her children.

She is a woman whose actions and decisions have led to a disconnect, not just with her family, but with herself. This emotional dislocation intensifies when she is seen in the context of her work, implying that her personal life has become secondary to external pressures.

Her refusal to acknowledge modern conveniences like smartphones suggests an additional layer to her character—one that is resistant to change and perhaps clinging to a form of resistance or self-imposed isolation. Her presence in the narrative highlights themes of abandonment, duty, and the clash between personal desires and societal expectations.

Leif

Leif, one of the central children in the story, is both the protector and caretaker within the family dynamic. As the sibling who attempts to navigate the complex emotional landscape left by their mother’s detachment, Leif takes on the responsibility of guiding his younger siblings through this strange new world.

His actions throughout the narrative suggest a deeply conflicted character who, while trying to protect his family, also feels the weight of their emotional burdens. Leif’s decision to lead his siblings away from the uncertainty of their current life and return to a home marked by strange red lines is symbolic of the larger theme of impermanence.

His role as caretaker is fraught with personal conflict, as he balances the emotional and physical demands of family life while struggling with his own feelings of detachment. Leif represents a person caught between the roles society expects him to fulfill and the deeper, more personal need for freedom and distance.

His journey reflects a constant battle between responsibility and the desire to break free from the cyclical nature of his familial obligations.

The Narrator’s Sister

The narrator’s sister stands in stark contrast to the other characters, embodying a free-spirited, nonconformist attitude. Her renaming of the horse to “Gliff” serves as a powerful act of rebellion against the rigidity of societal structures, showing her rejection of fixed identities and the constraints imposed by others.

Throughout the narrative, she moves through life with an air of defiance and curiosity, constantly questioning the boundaries of identity and existence. This fluidity in her actions and self-perception challenges traditional notions of belonging and identity, urging a more open, unrestricted way of experiencing the world.

The sister’s interaction with the world, particularly in her relationship with the horse, highlights the tensions between personal freedom and societal expectations. Through her eyes, we witness the exploration of names, labels, and the way they shape our understanding of self.

Her transformation of “Gliff” from just an animal into a symbol of both ownership and liberation provides a metaphor for how identity can be reclaimed and reinvented.

Colon

Colon is an eccentric and socially awkward character who serves as a foil to the more intuitive and emotionally intelligent characters in the narrative. His obsession with collecting data and categorizing others reflects the more oppressive, surveillance-driven aspect of society.

Colon represents the mechanistic, impersonal forces that attempt to reduce human beings to mere statistics, removing the complexity and individuality that define them. In contrast to the narrator’s more fluid and instinctive approach to identity, Colon clings to a rigid, bureaucratic worldview, which is particularly apparent in his interactions with the narrator and her sister.

The tension between Colon’s need for control and the siblings’ desire for autonomy further underscores the novel’s exploration of identity and surveillance. His presence in the story is a reminder of the dangers of dehumanization, where the focus shifts from the unique complexities of individuals to a world that seeks to categorize and control every aspect of their lives.

Saccobanda

Saccobanda is one of the most enigmatic figures in Gliff, embodying the raw power of nature and the world’s refusal to be controlled. When authorities declare her “unverifiable” and attempt to erase her from society, it sparks a widespread revolt not just from people, but from the elements of nature itself.

Saccobanda’s connection to nature is both spiritual and political—she represents the unyielding force of the natural world against societal and bureaucratic forces that seek to categorize and restrict it. Her removal from society is not just a personal loss but a collective awakening, as the forces of nature rise in response to her absence.

Saccobanda’s story speaks to the broader theme of resistance, not only from individuals but from the very fabric of existence itself. Her character serves as a symbol of rebellion against systems of control and a reminder of the power that can be harnessed when the natural world, with all its unpredictability and complexity, refuses to conform.

Bri

Bri, alongside her sister, navigates a world that seeks to define and control them. Her journey is marked by an exploration of language, identity, and the nature of connection.

As Bri confronts the societal structures that label and categorize individuals, she begins to understand the power of language both as a tool of connection and a method of control. Her curiosity about the relationship between words and reality becomes central to her development.

Bri’s journey is also one of self-discovery, as she uncovers the complexities of identity through her interactions with others, especially with those who, like her, are marginalized or erased from official records. Through Bri’s perspective, the story delves into the concept of “unverifiables,” individuals who exist outside of the systems that seek to categorize and label them.

Her exploration of language becomes a metaphor for the search for freedom and agency in a world where personal identity is often subject to external forces. Bri’s journey is not just about understanding language, but about reclaiming it as a means of forging deeper connections with herself and the world around her.

Ayesha Falcon

Ayesha Falcon is a pivotal character who helps guide the speaker through a series of reflections on trauma, identity, and agency. Her role is to challenge the speaker’s perception of their own limitations, especially when it comes to confronting barriers in both the dream world and reality.

Ayesha’s past, marked by survival and escape from a troubled life, makes her a symbol of resilience and defiance. Her wisdom and insights offer the speaker a path forward, urging them to confront the obstacles that hold them back.

The story she shares about the tyrant who tries to erase his opponent, only for the opponent’s legacy to grow stronger, speaks to the enduring power of resistance against oppressive forces. Ayesha’s character is both a guide and a mirror, reflecting the speaker’s struggles with their past and encouraging them to embrace the possibility of transformation.

Through Ayesha, the narrative explores the themes of memory, loss, and the potential for personal reinvention in the face of systemic oppression.

Themes

Identity and Self-Discovery

The journey of self-discovery is central to the experiences of the characters in Gliff. The notion of identity is explored deeply, especially as characters struggle to define themselves in a world that seeks to label, categorize, and control them.

The siblings, particularly Bri, navigate the complexities of identity through their interactions with the world and each other. Bri’s curiosity about language and her connection with the horse Gliff represent a deeper questioning of identity and belonging.

The act of renaming Gliff becomes symbolic of the fluidity of identity and the idea that names and labels, whether imposed or chosen, do not fully encompass the essence of being. The characters’ exploration of who they are is further complicated by their societal status as “unverifiable,” forcing them to confront the boundaries between personal freedom and the need for societal acceptance.

As they grapple with these pressures, the idea of self becomes more malleable, challenging traditional concepts of permanence and ownership. This theme of shifting identity speaks to the larger human experience of searching for meaning and understanding in an ever-changing world, where the pursuit of self-realization is both a personal and collective struggle.

Loss and Memory

Loss plays a pivotal role in shaping the characters’ emotional and psychological states throughout the narrative. The speaker’s recurring dreams about their sister serve as a poignant reminder of the absence that pervades their life.

These dreams, along with the symbolism of the door and the wall, evoke the separation of past and present, the known and the unknown. The imagery of the door represents not just physical separation but also the emotional distance that comes with time and loss.

Similarly, Ayesha’s story about the tyrant and his attempt to erase the legacy of his opponent echoes the theme of memory’s resilience. Despite efforts to destroy or suppress memory, it remains a powerful force, growing stronger with time.

The speaker’s recollection of their sister, even in dreams, reflects the deep impact that loss has on their identity. It becomes a source of both pain and strength, as the memory of the past shapes their journey toward self-discovery and healing.

Ultimately, the theme of loss highlights the way in which past experiences continue to influence and guide individuals, even when they are trying to move forward.

Rebellion and Resistance

Rebellion is a recurring theme in Gliff, particularly through the characters’ refusal to conform to societal expectations and oppressive systems. The removal of Saccobanda from society, labeled as “unverifiable,” sparks a revolt not just from the people but from the very elements of nature.

This rebellion symbolizes the collective power of those who have been marginalized, highlighting the strength that can arise when individuals come together to challenge systems of control. In a similar vein, the siblings’ resistance to the labeling and verification systems that seek to define them reflects a broader critique of societal structures that prioritize conformity over individuality.

The tension between freedom and control is felt throughout the narrative, as characters struggle to navigate a world that seeks to impose rigid definitions on them. The idea that resistance can come in many forms—whether through direct action or through the rejection of imposed labels—emphasizes the importance of personal autonomy and the need to question authority in order to achieve true freedom.

The Power of Language

The theme of language and its role in shaping reality and identity is explored through the characters’ interactions with words, names, and communication. Bri’s search for meaning in language highlights the fluid nature of words and their ability to both connect and divide.

The act of renaming the horse Gliff represents a challenge to the conventional use of language, as the name becomes a symbol of personal freedom rather than a societal imposition. This act of renaming contrasts with the societal need for categorization and control, underscoring the power that language has in defining not just objects but people themselves.

Through their exploration of language, the characters confront the limitations and possibilities that words hold, recognizing that language is not just a tool for communication but also a force that can shape the way we perceive the world. The narrative’s exploration of language emphasizes its dual role as both a means of connection and a mechanism of control, forcing the characters to navigate its complexities in their quest for identity and belonging.

The Struggle for Agency and Autonomy

At the heart of the narrative is the struggle for agency and autonomy in a world that constantly seeks to impose boundaries and limitations. The characters’ experiences with societal control—whether through the label of “unverifiable” or the need for categorization—reflect the broader challenges individuals face in trying to assert their own identities in the face of external forces.

This theme is particularly evident in the siblings’ journey, where their sense of freedom is continually tested by the systems that seek to define and constrain them. The rejection of societal labels, as seen in the characters’ refusal to be bound by traditional definitions of identity, represents a desire for autonomy and the right to self-determination.

Similarly, the revolt against Saccobanda’s removal from society symbolizes the fight for the right to exist outside the constraints of authority. The theme of agency is also reflected in the characters’ interactions with the natural world, where the forces of nature themselves seem to resist the control imposed by human systems.

Ultimately, the struggle for agency in Gliff speaks to the larger human desire for self-expression and freedom in a world that often seeks to limit both.

Social Critique and Corporate Malfeasance

A significant portion of the narrative also critiques the corporate and societal systems that perpetuate harm, particularly through the character of the mother, who becomes a whistleblower regarding harmful chemicals. This theme highlights the dangers of corporate malfeasance and the way in which profit motives often overshadow the well-being of individuals and the environment.

The mother’s decision to expose the truth about the company’s actions reflects the personal cost of standing up against such systems, as well as the broader consequences for society as a whole. This critique of corporate negligence serves as a powerful commentary on the role of big corporations in shaping the lives of individuals, particularly those who are already marginalized or vulnerable.

The story presents a world where societal indifference to suffering allows these systems of exploitation to persist, and the characters’ struggles to navigate this environment underscore the need for both individual and collective resistance to such injustices. Through the mother’s story and the wider narrative, Gliff presents a stark examination of the ways in which corporate interests intersect with personal lives, shaping the experiences of individuals and communities in profound and often harmful ways.