Go As a River Summary, Characters and Themes

Go as a River by Shelley Read is a poignant exploration of love, loss, family, and identity, set against the backdrop of a changing landscape. The story follows Victoria, a young woman navigating the complexities of her life in the small town of Iola, Colorado.

Victoria’s journey is one of self-discovery, as she deals with the death of her mother, the pressures of family life, and the emotional turmoil of a secret love affair with a mysterious drifter, Wilson Moon. As her connection with Wilson deepens, the novel delves into themes of displacement, societal expectations, and personal growth. The novel unfolds with a sense of quiet intensity, revealing how the past shapes identity and how one can find hope and meaning even in the most difficult circumstances.

Summary

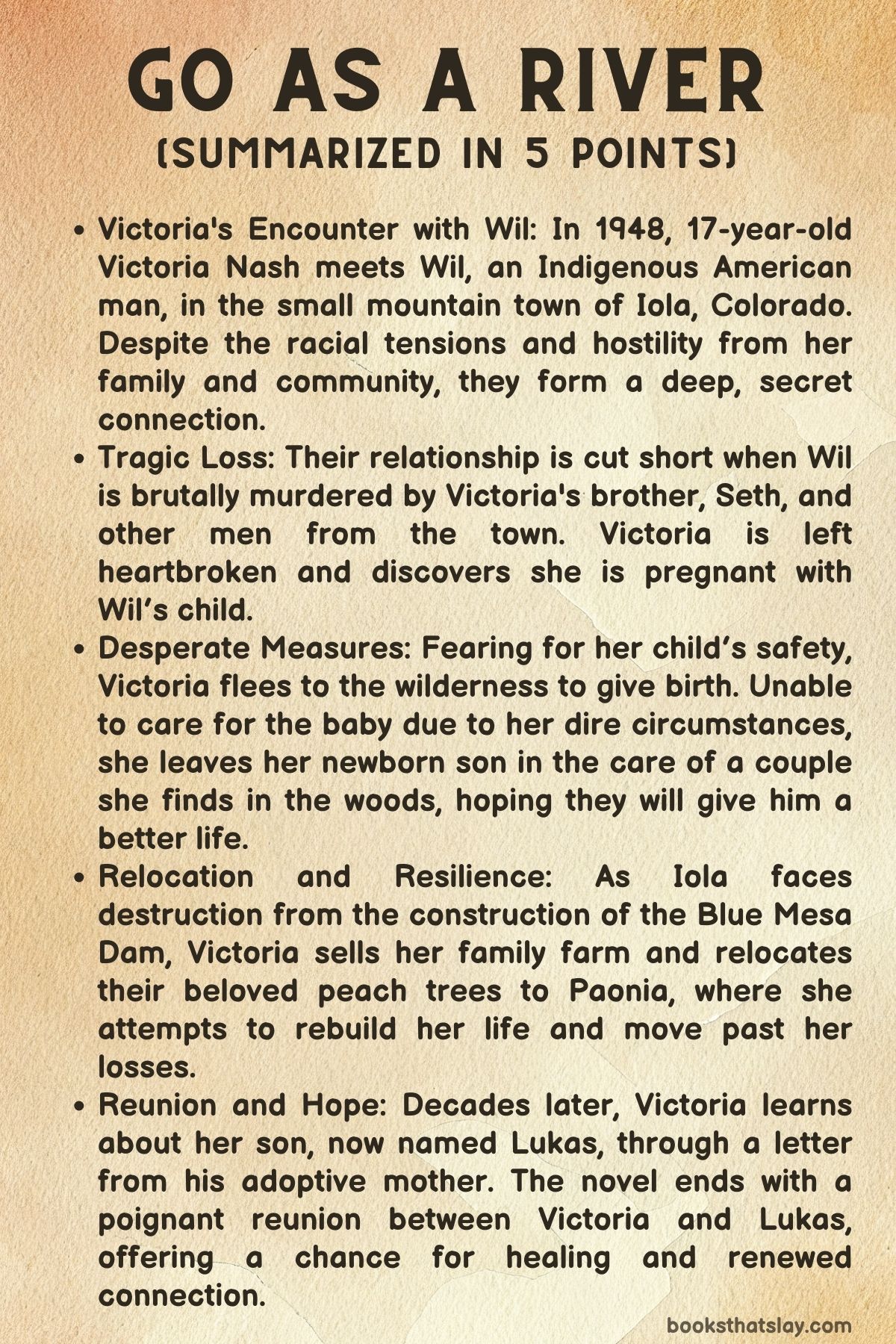

In 1948, Victoria Nash, a 17-year-old girl living on her family’s peach farm in Iola, encounters a stranger on the road, Wilson Moon, who introduces himself as Wil. He is an Indigenous American who has recently escaped a harsh life in Durango’s coal mines.

Despite the differences in their backgrounds, Victoria is drawn to Wil, and they form a connection. However, their relationship faces immediate hostility from Victoria’s brother, Seth, who harbors deep-seated racial prejudices.

After a heated altercation between Seth and Wil, tensions escalate in the small town. Wil becomes the target of widespread bigotry, falsely accused of theft and relentlessly pursued by Seth and other men who want to harm him. Fearing for his life, Wil goes into hiding, but he continues to meet Victoria in secret, deepening their bond.

Their relationship blossoms, and Wil becomes Victoria’s first lover. However, their happiness is short-lived. Wil suddenly disappears, and Victoria’s worst fears are realized when she learns that her brother has returned home covered in blood. Soon after, the town discovers the brutalized body of an Indigenous boy, presumed to be Wil, but the crime goes uninvestigated due to the pervasive racism of the era.

Months later, Victoria discovers she is pregnant with Wil’s child. Terrified that her brother or the townspeople might harm her baby, she flees to Wil’s secluded hut in the wilderness to give birth.

After a challenging delivery, she revives her seemingly stillborn son using a technique Wil had taught her. But with no resources and weakened from childbirth, Victoria and her newborn begin to starve.

In desperation, she leaves the baby in a car belonging to a couple she finds picnicking in the woods, hoping they will take him in. They do, leaving a single peach behind as a sign that they have found the child.

Victoria, now alone, returns to the family farm, only to find that her father is dying, and Seth has left town. After her father’s death, Victoria discovers he turned Seth in for Wil’s murder, but Seth was released due to insufficient evidence.

Isolated and grieving, Victoria maintains the peach farm until news arrives that Iola will be flooded to create a reservoir. She decides to sell the farm and relocates the family’s peach trees to a new valley in Paonia, defying the townspeople’s scorn.

Years later, Victoria remains haunted by the memory of her abandoned son. She regularly visits the spot where she left him, creating a memorial with stones. After 20 years, she finds a letter from the woman who adopted her son, revealing that his name is Lukas.

The letter explains how Lukas discovered the truth about his origins and left to fight in the Vietnam War, leaving his adoptive mother desperate to reconnect with him. Finally, Victoria gathers the courage to meet Lukas.

The novel concludes with their reunion, as mother and son take tentative steps toward each other, hinting at the possibility of reconciliation and healing.

Characters

Victoria Nash

Victoria Nash is the protagonist of “Go As a River.” Her character is central to the novel’s exploration of displacement, loss, and resilience. As a 17-year-old, Victoria is introduced as a dutiful daughter and hardworking peach farmer. She lives in a male-dominated household where her role is largely defined by her ability to serve her volatile father and brother.

However, her encounter with Wilson Moon catalyzes a profound transformation in her life. The relationship with Wil, which begins with an intense but forbidden attraction, propels Victoria into a journey of self-discovery and defiance.

Her character is marked by a quiet strength and an unyielding will to survive, even in the face of immense personal tragedy. The loss of Wil, the abandonment of her child, and the eventual destruction of her hometown through the dam project all shape Victoria into a figure of resilience.

Despite these hardships, she retains a deep connection to her land and heritage. This connection is symbolized by her decision to transplant her family’s peach trees to a new location.

Her journey towards reconciliation with her past, particularly in her decision to meet Lukas, her son, in the novel’s closing, signifies her enduring hope and capacity for love, even after years of pain.

Wilson Moon (Wil)

Wil is an Indigenous American traveler whose brief yet significant relationship with Victoria forms the emotional core of the novel. Wil embodies themes of racial injustice, displacement, and the search for identity.

His background as a coal miner and his status as a drifter reflect the limited opportunities and systemic racism faced by Indigenous people in mid-20th century America. Wil’s gentle demeanor and profound connection to nature stand in stark contrast to the brutality and prejudice he encounters in Iola.

His love for Victoria is portrayed as pure and transformative, yet it also places him in danger due to the deep-seated racism of the town. Wil’s tragic fate—being hunted and killed because of his race—serves as a powerful commentary on the violence inflicted upon marginalized communities.

His memory, however, lives on through Victoria and their son Lukas. Wil becomes a symbol of enduring love and resilience in the face of oppression.

Seth Nash

Seth Nash, Victoria’s younger brother, is a complex character defined by his volatility, deep-seated insecurities, and the influence of a racist and patriarchal environment. Seth’s alcoholism and violent tendencies are symptomatic of the toxic masculinity that permeates the Nash household.

His hostility towards Wil is driven by both racial prejudice and a desire to assert his dominance, reflecting the societal attitudes of the time. Seth’s role in Wil’s death, though he is not the direct killer, reveals the extent to which he is complicit in the violence that ultimately shatters his family.

His relationship with Victoria is fraught with tension. She represents both a sibling and a moral counterpoint to his destructive behavior. Seth’s eventual departure from Iola, following his father’s betrayal and the collapse of the family unit, marks the end of his influence over Victoria’s life. This allows her to break free from the oppressive environment in which she was raised.

Forrest Davis

Forrest Davis is a farmhand who works on the Nash family farm and becomes an accomplice in the murder of Wil. His character represents the more insidious forms of racism that permeate the community. Violence against marginalized individuals is normalized and even encouraged.

Unlike Seth, who is driven by personal vendettas, Davis’s actions seem to stem from a broader societal acceptance of racial violence. His involvement in Wil’s murder and the subsequent lack of accountability reflect the systemic injustices that allow such crimes to go unpunished.

Davis’s character serves as a foil to Wil, highlighting the deep moral divide between those who perpetuate violence and those who fall victim to it.

Inga

Inga is the woman who adopts Victoria’s son after she leaves him in the woods. Her character is essential to the novel’s exploration of motherhood, identity, and the complexities of love. Inga represents the maternal figure that Victoria could not be for her son, providing him with a stable home and upbringing.

However, her decision to withhold the truth about Lukas’s origins from him until he is an adult creates a rift between them. This illustrates the challenges and ethical dilemmas of adoptive motherhood.

Inga’s letter to Victoria is a poignant moment in the novel. It reveals her desperation and regret over the choices she made, as well as her deep love for Lukas. Through Inga, the novel examines the different forms that motherhood can take and the sacrifices and decisions that define a mother’s love.

Lukas

Lukas, the son of Victoria and Wil, is a character who represents the intersection of past and present, and the potential for healing and reconciliation. Although he is absent for much of the novel, his presence is felt through Victoria’s memories and her enduring hope that he is alive and well.

Lukas’s decision to join the army after discovering the truth about his origins reflects his struggle with identity and belonging. These themes are central to the novel.

His appearance at the end of the novel, as a young man who bears a striking resemblance to Wil, is a powerful symbol of continuity and the enduring legacy of his parents’ love.

Lukas’s reunion with Victoria offers a glimmer of hope and redemption, suggesting that even after years of separation and hardship, it is possible to rebuild connections and move forward.

Victoria’s Father

Victoria’s father is a stern and controlling figure, embodying the harshness of life in a patriarchal, rural society. His character is defined by his rigid adherence to traditional values, particularly in his role as the head of the Nash family.

His treatment of Victoria and his deep-seated racism contribute to the oppressive environment in which she grows up.

His eventual betrayal of Seth, by turning him in to the authorities for Wil’s murder, reveals a complex moral code that is influenced by both personal and societal pressures.

His death marks the end of an era for Victoria, allowing her to step out of his shadow and begin to forge her own path.

Ruby-Alice

Ruby-Alice is a minor character who plays a significant role in providing shelter to Wil and helping to conceal his presence in Iola. She is portrayed as an eccentric figure, shunned by the townspeople due to rumors of mental illness.

However, her actions reveal a deep sense of compassion and solidarity with those who are marginalized. Ruby-Alice’s character challenges the stigma associated with mental illness and demonstrates the importance of empathy and support in a community that is otherwise hostile and intolerant.

Themes

Displacement and Loss

The theme of displacement is central to Go as a River, particularly as it explores the effects of the Blue Mesa Reservoir on the protagonist’s hometown of Iola. The narrator’s vivid recollection of Iola, once a vibrant town, now submerged under water, symbolizes not only the physical loss of a community but also the emotional erasure of a past that can never be reclaimed.

The flooding of Iola mirrors how the traumatic events in life can drown out memories and physical landmarks, but the emotional and psychological scars remain, shaping who we are. The townspeople’s forced migration reflects the broader human experience of displacement, whether by natural disasters, societal changes, or personal upheavals.

It shows how even when a place is physically erased, its influence endures, both in the narrator’s memories and in the very fabric of her identity. For Victoria, this theme of displacement is also personal as she navigates the loss of her family’s farm, the death of loved ones, and the difficulties of finding a place where she feels truly at home.

This theme extends to the broader idea that people are often uprooted—whether by circumstance or choice—and must find new ways to rebuild their lives and identities.

Identity and Belonging

The exploration of identity in Go as a River is intricately tied to the protagonist’s emotional journey and her relationships. Victoria’s evolving sense of self is shaped by her complicated family life, her grief over the loss of her mother, and the intense emotional connection she forms with Wilson Moon.

Initially, Victoria is deeply influenced by her family’s values and societal expectations, which confine her within a rigid framework of right and wrong. However, her interactions with Wilson, who embodies a different perspective on life, challenge her preconceived notions and force her to reconsider her own identity.

Wilson’s mistreatment due to his Native American heritage and the prejudices he faces serve as a stark reminder of how society defines people based on arbitrary distinctions. Victoria’s relationship with him compels her to confront her own biases and question the values instilled in her.

This internal conflict and the resulting shift in Victoria’s identity are emblematic of the broader struggle for self-discovery, as she grapples with the tension between her family’s expectations and her own desires for freedom and connection. Her journey of self-identity also involves her response to loss and the choices she must make in the aftermath, ultimately shaping the person she becomes.

Grief and Healing

Grief plays a profound role in shaping the emotional trajectory of Go as a River, and it is portrayed not only as a process of mourning but also as a source of transformation. Victoria’s grief is multifaceted—stemming from the death of her mother, the collapse of her family, and the tragic loss of Wilson Moon.

These losses set her on a path where she must reconcile the pain of the past with the need for personal growth. The novel portrays grief as a heavy, suffocating force, yet also as a catalyst for change, forcing Victoria to confront her deepest fears and uncertainties.

As she retreats into isolation after Wilson’s death and her pregnancy, the wilderness becomes both a literal and symbolic space for healing. Her time away from society allows her to process her emotions and find a form of peace amidst the chaos of her past.

This theme emphasizes that healing does not occur overnight; it is a long, arduous process that involves accepting the weight of past traumas while learning to move forward. The forest, where Victoria gives birth and contemplates her future, represents the nurturing aspects of nature, offering her both refuge and strength in her healing journey.

The novel ultimately suggests that while grief is a force that may never fully dissipate, it can also lead to growth, understanding, and the ability to embrace new beginnings.

The Struggle for Love and Connection

The theme of love and connection is explored through the complex relationships that Victoria forms with Wilson, her family, and ultimately her own sense of self. Victoria’s yearning for love is deeply influenced by the absence of her mother and the fractured relationships within her family.

Her connection with Wilson represents an escape from the rigid boundaries of her upbringing, offering her a glimpse of emotional freedom and tenderness. However, their love is not without obstacles.

The societal prejudices surrounding Wilson’s background, the judgments of Victoria’s family, and the secrecy of their relationship add layers of tension to their bond. As Victoria navigates these challenges, her desire for connection is tested by the harsh realities of the world she inhabits, where love is often tainted by fear, misunderstandings, and external pressures.

The development of their relationship also highlights the theme of self-love, as Victoria must learn to embrace her own desires and emotions, rather than suppress them in favor of societal expectations. The tension between longing for love and the fear of rejection or judgment is a key aspect of the narrative, illustrating how deeply personal connections can become complicated by broader social forces.

Ultimately, the novel shows that love, in all its forms, is a journey of vulnerability, sacrifice, and the courage to embrace one’s true feelings despite the barriers that may exist.

The Power of Nature and the Landscape

In Go as a River, nature is not merely a backdrop to the narrative but a force that interacts with and shapes the characters’ emotional and psychological landscapes. The river, the forest, and the land all play symbolic roles in the novel, reflecting the characters’ inner turmoil and their journeys toward self-discovery.

Victoria’s time in the wilderness after Wilson’s death is a period of intense emotional reckoning, where the natural world becomes a mirror for her internal state. The forest, which she initially views as an intimidating and isolating place, gradually transforms into a space of self-reliance and introspection.

Nature provides her with the tools to survive and the space to heal, and its rhythms become an anchor for her as she moves through her grief. This connection to the landscape also reflects the broader theme of belonging, as Victoria learns to find her place within the natural world, much as she learns to reconcile her place in the human world.

The novel suggests that while humans often seek solace in others, the natural world offers a unique form of healing—one that requires patience, resilience, and acceptance of life’s cyclical nature.