Good Girl by Aria Aber Summary, Characters and Themes

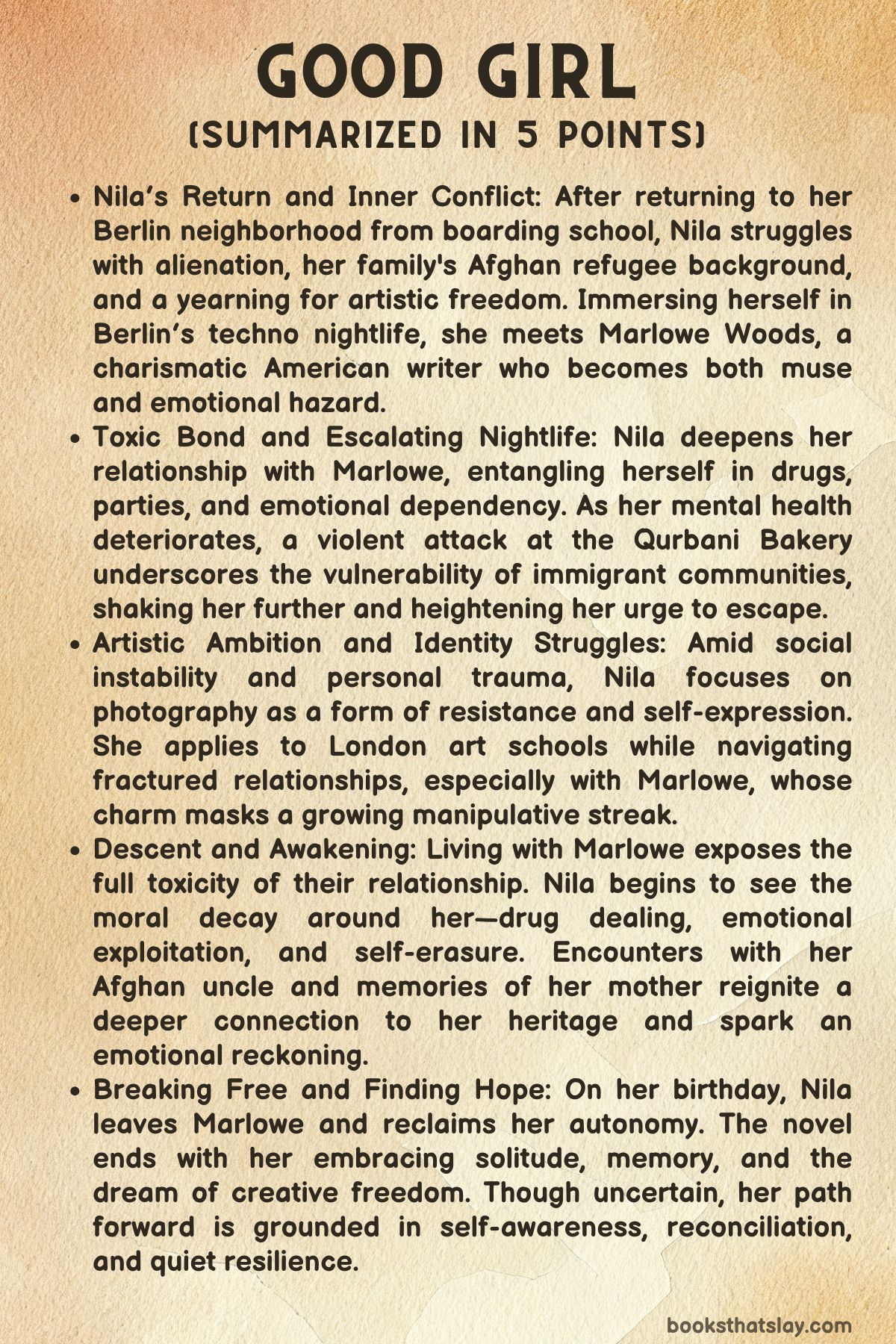

Good Girl by Aria Aber is a searing portrait of dislocation, longing, and survival through the eyes of Nila, an Afghan-German teenager coming of age in contemporary Berlin. Oscillating between memory, trauma, and desire, Nila’s story captures the raw, fragmented journey of a young woman navigating class, race, family estrangement, sexual violence, and the volatile search for self.

Aber’s prose is intimate and emotionally charged, steeped in the textures of nightlife, fractured identities, and the quiet ache of being unmoored in a world that refuses to offer refuge. Through Nila’s voice, the novel interrogates the complexities of womanhood and cultural inheritance in a Europe that often denies both.

Summary

Nila, at eighteen, returns to her family’s apartment in Berlin after time spent at boarding school. Her arrival is marked not by warmth or welcome, but by physical and emotional decay—the smell of urine in the elevator, graffiti-streaked walls, and the hollow silence of her home.

In the solitude of her childhood bedroom, Nila lies beneath her deceased mother’s dress, seeking comfort in memories and symbols of a past that no longer fits. That bedroom, cramped and unchanged, becomes a metaphor for her emotional suffocation and latent desire to escape the grip of grief and cultural inheritance.

She begins attending Humboldt University, not out of academic drive, but simply to receive a transit pass. Her days quickly shift toward Berlin’s techno nightlife scene, a place where the chaotic pulse of clubs and substances offers a momentary suspension of alienation.

At work, she encounters microaggressions and invasive questions that reduce her to an ethnic stereotype. Her body becomes a space of conflict, simultaneously desired and objectified, both invisible and hyper-visible.

This discomfort becomes part of her internal war—a search for belonging in a society that repeatedly marginalizes her.

In a pivotal scene at “the Bunker,” a techno club steeped in myth and anonymity, Nila meets Marlowe Woods, a renowned American writer. Their chemistry is immediate but tinged with imbalance: he is older, lauded, mysterious.

Their first encounter is charged with intoxication and confusion, balancing between coercion and consent. For Nila, Marlowe is not just a man, but a symbol—of freedom, success, and the artistic transcendence she craves.

Yet their intimacy is founded on performance. She lies about her ethnicity, claiming to be Greek, shielding herself from the shame and scrutiny of her Afghan-German identity.

The following day she visits her father’s apartment, where silence, grief, and displacement press against her. Once a doctor in Kabul, he now drives a taxi; her mother, also a physician, died in Berlin after years of working as a caregiver.

Their immigration story—riddled with loss, downward mobility, and bureaucratic indifference—casts a shadow over Nila’s aspirations. The cramped housing and unspoken trauma of Gropiusstadt are not just settings, but the architecture of her inheritance.

Her photographic work—emotive, rough, tender—becomes an act of reclamation, echoing her admiration for artists like Nan Goldin, who document beauty in the margins.

As weeks pass, Nila grows obsessed with Marlowe, hanging around his literary circles, altering her appearance, chasing the mirage of connection. Meanwhile, her relationships with friends begin to fracture.

Her flatmates, Romy and Anna, evolve past their mutual hedonism, distancing themselves emotionally and socially. Nila spirals inward, wounded by abandonment and hierarchy, eventually suffering another ambiguous sexual experience in a club that further blurs the lines between agency and violation.

Eli, a friend from boarding school, reappears and becomes a brief emotional anchor. Through him, Nila is drawn into the world of Doreen, Marlowe’s current girlfriend.

Their meeting is unexpected, a drug-fueled, emotionally naked moment shared in the bathroom of a club. Doreen’s confessions of loneliness and disenchantment with Marlowe both alarm and resonate with Nila.

Their temporary solidarity reflects the broader landscape of unfulfilled desires and emotional scarcity that defines Nila’s experiences with intimacy.

As the story shifts, Nila’s narrative begins to move inward. Flashbacks to her childhood and adolescence reveal a home shaped by violence, silence, and complex gender dynamics.

Her relationship with her mother—at once tender and punishing—is filled with emotional intensity, particularly around the trauma of a miscarriage Nila witnessed. The emotional residue of that event lingers in her psyche, coloring her view of female suffering and familial bonds.

When Marlowe re-enters her life more fully, their dynamic becomes a disorienting mix of mentorship, lust, and power play. He offers her a camera, speaks of artistic vision, and takes her into his home, where their relationship shifts toward daily proximity.

Yet, the emotional and physical intimacy is erratic and often toxic. Marlowe’s charisma masks deep control; his actions swing between warmth and cruelty.

He treats Nila as both muse and pupil, collapsing the boundary between personal and professional, desire and dominance.

As Nila continues photographing him and her surroundings, her artistic voice begins to sharpen. Yet her identity remains tethered to his validation.

The lines blur further during a festival that is anarchic and unsettling. Marlowe is emotionally unavailable and sexually coercive, eventually cheating on her.

Amid this chaos, Nila stumbles upon a street named after Meena Keshwar Kamal, a feminist icon from Afghanistan. This accidental encounter ignites a moment of profound clarity: she is the descendant of a legacy of resistance, not just trauma.

Her identity, so long suppressed, becomes a wellspring of strength rather than shame.

The relationship with Marlowe ends. Nila leaves his apartment, moves in with a friend, and begins the painful process of restoration.

Photography remains her anchor. She documents bruises, her own face, her dead mother, and even Marlowe.

In doing so, she creates a visual language for her internal landscape—a mosaic of pain, inheritance, and becoming.

The wider world encroaches again in the form of neo-Nazi violence. A series of murders across Germany, including one near her neighborhood, reminds Nila of the constant threat faced by immigrants.

The media spectacle surrounding these deaths brings her face-to-face with her own survivor’s guilt and deepens her sense of responsibility to remember, to witness, to create. She visits the graves of the murdered Qurbani brothers, a silent act of grief and defiance.

Her journey culminates in a quiet moment with her father, who reveals the story of her name—after the Kabul river, Nila. The intimacy of this exchange allows Nila to reclaim a sense of lineage, not as burden, but as inheritance.

She is later accepted to an art school in London, a city offering possibility and distance. As she prepares to leave Berlin, she walks not into certainty, but into a future that feels increasingly hers.

In embracing her past, her body, her voice, and her art, Nila steps closer to becoming whole.

Characters

Nila

Nila is the profoundly complex protagonist of Good Girl, through whom the narrative’s emotional and political terrain unfolds. As an eighteen-year-old Afghan-German woman returning to Berlin from boarding school, she exists in a liminal space—torn between cultural inheritances, artistic ambitions, and the weight of her past.

Nila’s character is driven by a dual hunger: the need to escape the suffocating realities of immigrant trauma and the yearning for self-definition through art, love, and sensual experience. Her identity is deeply fractured; she lies about her Afghan roots to avoid racial scrutiny, even as she finds herself increasingly tethered to the cultural memory of her family’s displacement.

Her internal world is saturated with grief—her mother’s death, her father’s decline, her own childhood wounds—and this sorrow is both numbed and animated through Berlin’s techno scene, casual sex, and substance use. Nila’s obsessive attachment to Marlowe, and her complicated romance with Setareh, reveal her desire to be seen and loved wholly.

Her trajectory, from a girl seeking refuge in others to a woman reclaiming her artistic and cultural voice, becomes the narrative’s most poignant arc. Ultimately, Nila’s survival is not just emotional but creative—photography becomes her means of preservation and reclamation, a tool to narrate her own pain and personhood with dignity.

Marlowe Woods

Marlowe Woods is a seductive, mythologized American writer whose charisma and artistic success symbolize everything Nila craves: escape, prestige, and validation. His presence in Good Girl is both intoxicating and ominous.

Marlowe initially appears as a figure of artistic promise, gifting Nila a camera and urging her to take her photography seriously. However, beneath his bohemian veneer lies a manipulative and emotionally volatile man.

Their relationship, marked by drug-fueled intimacy and psychological power games, is riddled with ethical ambiguity. Marlowe vacillates between tenderness and cruelty, encouragement and humiliation.

He exploits Nila’s vulnerability and elevates her as a muse while denying her emotional reciprocity. Their connection descends into abuse—coercive sex, psychological dominance, and betrayal—highlighting the imbalance in their dynamic and the cost of Nila’s romantic idealism.

As a character, Marlowe embodies the dangers of artistic idolatry and the seductive violence of power. He is not merely a toxic lover, but a figure that catalyzes Nila’s eventual self-emancipation.

Setareh

Setareh represents one of the most tender and quietly devastating influences in Nila’s life. A fellow Afghan girl working at a gelateria in Venice, Setareh becomes the center of Nila’s first queer love story.

Their relationship, though brief and secretive, offers Nila a reprieve from the violence and disorientation that mark much of her adolescence. Setareh’s presence is marked by gentleness, intimacy, and a shared cultural understanding that does not need explanation.

Her departure, without confrontation or closure, devastates Nila and leaves her clutching remnants of their bond as sacred tokens. Setareh becomes a phantom of what could have been—a symbol of pure, mutual longing unburdened by the distortions of power and dominance.

Through Setareh, Good Girl articulates the fragility and intensity of queer, cross-cultural connection in a world hostile to both.

Elias (Eli)

Elias is a friend from Nila’s boarding school who reenters her life during a time of immense chaos. Unlike Marlowe or the transient figures in Berlin’s club scene, Eli provides Nila with a sense of continuity and emotional refuge.

He is neither savior nor romantic foil, but someone who understands the disjointed emotional terrain of her life without demanding explanation. Eli’s own entrenchment in the same nightlife and artistic circles gives him credibility in her world, yet he functions more as a grounding presence than an enabler.

Through Eli, Nila gains a clearer understanding of the social hierarchies and performances that define their youth. His inclusion in the story underscores the importance of platonic constancy and shared history amid relational volatility.

Doreen

Doreen is both an extension of and a foil to Marlowe. As his girlfriend, she should be an object of rivalry for Nila, but instead becomes a surprising source of connection.

Their moment of vulnerable, drugged-out camaraderie in a club bathroom reveals the shared emotional neglect they suffer under Marlowe’s influence. Doreen is both more jaded and more resigned than Nila, her loneliness masked by performative social grace and insider status.

Her confession about the hollowness of her relationship with Marlowe helps destabilize the pedestal on which Nila has placed him. Doreen, like Nila, is a woman surviving in proximity to a powerful man, and her candidness becomes a brief but meaningful act of solidarity.

Her character reframes the narrative, turning what could have been a clichéd love triangle into a critique of male-centered relationships and female disempowerment.

Nila’s Mother

Nila’s mother, though deceased at the story’s beginning, is a haunting presence throughout Good Girl. Her character is rendered in fragments—memories, dreams, physical pain, and emotional tension.

A former doctor demoted to caregiving labor in exile, she symbolizes the generational loss experienced by displaced professionals. Her relationship with Nila is defined by contradiction: tenderness interspersed with cruelty, silence marked by fierce maternal protectiveness.

Her sudden death severs Nila’s last connection to unconditional love, yet her influence lingers as a source of both trauma and strength. The miscarriage Nila witnesses becomes an emblem of shared suffering, a physical and psychological wound that binds them.

Her ghost is not romanticized, but rendered with unflinching realism—an emblem of all the women whose strength is never fully recognized.

Nila’s Father

Nila’s father is a quiet, grief-stricken figure whose life reflects the tragic displacement of immigrants forced to abandon their identities. Once a doctor in Kabul, he is reduced to a taxi driver in Berlin—a demotion that mirrors his emotional withdrawal and sense of defeat.

His apartment, bleak and silent, represents the stagnant grief that permeates Nila’s childhood. Yet, in the final chapters, a more nuanced portrait of him emerges.

His recounting of why he named Nila after the Kabul river becomes a rare moment of tenderness, offering her a symbolic link to her heritage. Though unable to fully support or understand her, he embodies a kind of dignity—one rooted in endurance, not expression.

His character complicates the narrative of patriarchy, offering a glimpse of quiet, sacrificial fatherhood amid cultural ruin.

Romy and Anna

Romy and Anna, Nila’s flatmates, function as subtle but telling barometers of her social and emotional descent. Romy withdraws into self-care and detachment, while Anna rises socially, adapting with an ease that both frustrates and alienates Nila.

Their changing dynamics—pasta dinners turned to distant silences—mirror Nila’s growing isolation. Yet, these women also serve as touchstones for what Nila’s life might have been without the chaos of trauma and obsession.

Their roles are not deeply dramatized, but they are essential in illustrating the shifting ground of female friendship, especially when juxtaposed against Nila’s entanglements with toxic masculinity.

Meena Keshwar Kamal

Though not a character in the traditional sense, the brief moment when Nila encounters a street named after Meena Keshwar Kamal—an Afghan feminist revolutionary—acts as a pivotal symbolic intervention. Kamal’s memory jolts Nila into an awakening, reminding her of the strength embedded in her cultural history.

This encounter marks a critical shift from victimhood to agency. It allows Nila to reclaim her Afghan identity not as a source of shame, but as a legacy of resistance.

Kamal’s ghost becomes a guiding force, anchoring Nila’s transformation and self-acceptance. Through this moment, Good Girl ties personal survival to collective memory, emphasizing the intergenerational power of feminist resistance.

Themes

Identity and Displacement

Nila’s life is marked by an unresolvable tension between her inherited Afghan identity and her fragmented experience in Berlin. This theme is not approached as a binary conflict but as a chronic state of restlessness, where her cultural belonging is both a burden and a mystery.

She does not reject her background outright, but she lies about it when necessary—to gain social acceptance, to shield herself from racial scrutiny, and to avoid invoking a heritage saturated with exile, war, and unfulfilled potential. Her self-perception shifts depending on the gaze of others, especially in spaces like clubs, classrooms, and galleries, where her Afghan-German identity is either invisibilized or exoticized.

The alienation is further intensified by her awareness of class within immigrant circles, where even those who share a similar ethnic background may not share the same economic or aspirational struggles. Her family’s descent from respected medical professionals in Kabul to underpaid laborers in Berlin functions as a symbol of cultural erosion and socio-economic demotion.

Through Nila’s emotional responses—ranging from shame to rage—Good Girl captures the pervasive disorientation that comes with being neither fully assimilated nor rooted, always navigating the fault lines between worlds.

Gender, Power, and Sexuality

The terrain of gender in Good Girl is unstable, often treacherous, and always charged with power dynamics. Nila’s sexual experiences frequently hover between autonomy and coercion, underscoring how young women’s desire can be simultaneously expressive and exploited.

Her encounters, especially with Marlowe and other older men, are rarely free of manipulation or imbalance. The club scenes, filled with fleeting seductions and drug-induced haze, are not just about hedonism but about testing boundaries of control, survival, and self-harm.

These moments are interspersed with the psychological inheritance of her mother’s experience—where womanhood was shaped by suffering, expectation, and a suffocating devotion. Nila’s desire for validation often emerges through romantic or sexual entanglements that mirror rather than resist patriarchal structures.

Even her relationship with Marlowe, which oscillates between intimacy and cruelty, reveals how young women are often groomed into tolerating humiliation under the guise of artistic mentorship or love. Her queerness, briefly illuminated through her romance with Setareh, offers a contrast—tender, secretive, and cut short by social and cultural constraints.

This relationship lingers as a quiet counterpoint to her more destructive relationships with men, suggesting that her understanding of desire is deeply tied to questions of safety, self-erasure, and belonging.

Artistic Expression as Survival

For Nila, art is not a hobby or even an ambition in the traditional sense—it is a necessity, a means of rewriting reality and preserving her inner life. Her camera becomes a tool of reclamation, capturing fleeting scenes that hold emotional weight: bruises, lovers, her family, moments of intimacy or despair.

Her obsession with Nan Goldin’s work is not simply about aesthetic admiration; it’s about seeking a visual language that validates her existence without demanding apology. The photographs she takes, especially those involving Marlowe, begin as gestures of idolization but evolve into a means of asserting perspective.

Her art reflects her instability and growth, documenting a world where everything is transient except the feeling. The act of developing film and watching the images appear becomes a form of quiet self-anchoring amid the chaos of her relationships and emotional spirals.

Her eventual application to art school in London signifies more than academic ambition—it is an assertion that her life, with all its pain and confusion, has meaning worth documenting. In this way, artistic practice is positioned not just as therapy or escape, but as a resistant act, a way of imposing narrative and control over experiences that are often chaotic or degrading.

Grief and Generational Trauma

Nila’s coming-of-age is profoundly shaped by the shadow of her parents’ displacement and the death of her mother, events that linger in her emotional and bodily memory. Her parents’ professional demotion from doctors to service workers is not just a tale of immigrant hardship—it is a transmission of unrealized dreams and social collapse that Nila absorbs in ways she doesn’t fully understand.

The emotional atmosphere of their home is thick with silence, sacrifice, and shame. Her mother, in particular, embodies a paradox of cruelty and care.

Their relationship is riddled with moments of deep intimacy and sharp violence, culminating in the traumatic miscarriage Nila witnesses as a child. This memory becomes a foundational trauma, shaping her understanding of womanhood, suffering, and familial love.

Her father’s own silence—both literal and emotional—underscores the loss of language and status that accompanies exile. The theme of grief in Good Girl is not episodic but ambient, existing in the walls of their high-rise apartment, in the broken rituals of meals and conversations, and in Nila’s impulse to forget and remember at once.

The intergenerational nature of trauma becomes clear as Nila begins to recognize how much of her behavior—her emotional volatility, her fear of abandonment, her attraction to suffering—is shaped by this legacy.

Obsession and Emotional Dependency

Obsession in Good Girl operates as a symptom of deeper loneliness and an inability to process pain through conventional means. Nila becomes emotionally tethered to Marlowe not because of love but because of the illusion of recognition and elevation he provides.

He sees her, talks to her about art, encourages her talent—yet these moments are inseparable from condescension, manipulation, and control. Her fixation with him mimics addiction: she returns to him despite the emotional and physical harm he causes, justifying his cruelty with fantasies of artistic kinship or misunderstood genius.

This obsession eventually infects her understanding of herself, as her identity becomes increasingly defined by her role in his world—muse, lover, pupil. The pattern repeats in other relationships as well, whether with Setareh, Eli, or Doreen.

Her hunger for closeness often results in distortion of reality, self-effacement, and emotional spiraling. The intensity of these attachments is not framed as romantic or dramatic, but as a psychological pattern rooted in loss, self-loathing, and a longing to matter to someone fully.

The slow unraveling of this dynamic, culminating in her decision to leave Marlowe and pursue art independently, marks a shift—still uncertain, still painful—but toward autonomy.

Violence, Memory, and Resistance

The ambient violence in Good Girl is not limited to personal relationships. It permeates the cultural and political atmosphere of Berlin, particularly in the form of racist attacks that echo Nila’s own fears.

The murder of the Qurbani brothers in a nearby bakery becomes a focal point for her reflections on targeted violence, survival guilt, and the disposability of immigrant lives in German society. The official responses to these killings—the media narratives, the political posturing—only amplify her disillusionment.

Yet these moments also serve as a point of clarity. Her decision to visit their graves and her eventual act of mourning are subtle but powerful gestures of resistance.

They anchor her in a history that is both collective and personal, reminding her that silence is complicity. Her decision to photograph and remember becomes an act of political agency, a refusal to let trauma be buried under bureaucracy or aesthetic distance.

In this way, the theme of violence transcends individual suffering to engage with broader systems of erasure, racism, and denial, while her response to it—grieving, remembering, creating—marks the beginning of a new kind of self-possession.