Good Girls Don’t Die Summary, Characters and Themes

Good Girls Don’t Die by Christina Henry is a genre-blending feminist psychological thriller that flips familiar tropes on their heads.

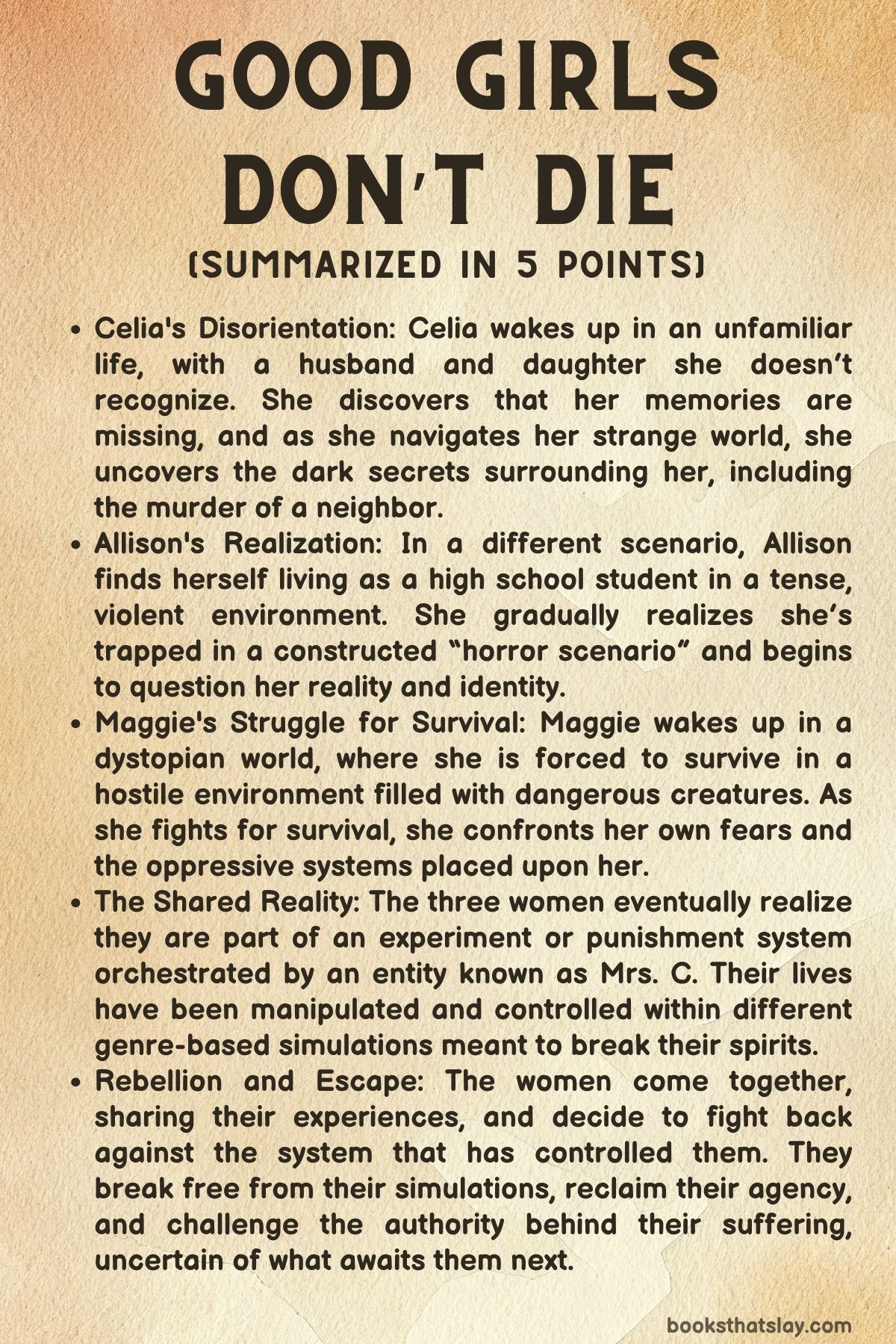

Christina Henry crafts a sharp, unsettling story where three women—Celia, Allison, and Maggie—wake up in twisted versions of familiar genre worlds: a suburban cozy mystery, a high school horror, and a dystopian survival tale. Each woman is forced into a role, stripped of her memories, and placed under the watchful eye of an unseen authority. What starts as disorientation becomes a fight for identity, truth, and resistance. It’s smart, chilling, and ultimately a story about reclaiming power in a world built to suppress it.

Summary

The novel is structured in four distinct parts, each told from the perspective of a different woman.

While the settings and tone shift dramatically between parts, all the women share something crucial: they’re trapped in fabricated realities designed to punish, manipulate, and observe them.

Part I: Celia

Celia wakes up in what seems to be an ordinary suburban life. She’s told she’s a wife and mother named Celia Zinone, running an Italian restaurant with her husband, Pete, and raising a daughter, Stephanie.

But Celia has no memory of this life and feels like an actor in someone else’s script. She plays along, unsure if she’s lost her memory or if something more sinister is at play.

At the restaurant, Celia deals with hostile customers and creepy neighbors, especially Mrs. Corrigan—a racist woman who falsely accuses Celia of assault. Celia’s fear intensifies when Mrs. Corrigan’s body turns up in a dumpster behind the restaurant, her throat slit.

The murder, the accusations, and the sense that she’s being watched all push Celia to question the nature of her reality. Her instincts scream that this isn’t real—and that someone is testing her.

Part II: Allison

Allison finds herself back in high school, a teenager again, surrounded by friends she vaguely remembers and others she doesn’t recognize at all. The setting feels like a typical young adult thriller, but it quickly turns dark.

There’s a school lockdown, rising paranoia, and people begin dying. Like Celia, Allison has no real memory of how she got there, but she remembers her actual life—before all this.

She begins to understand that this isn’t a dream or time travel, but some kind of simulation.

The world around her plays out like a slasher film, forcing her into the “final girl” trope. Unlike Celia, Allison is more aggressive and skeptical from the start. She begins resisting the narrative, refusing to follow the expected script.

Part III: Maggie

Maggie wakes up in a dystopian forest, chased by monstrous creatures and armed with only survival instincts. This segment is pure apocalyptic fiction: ruined facilities, government control, and a desperate fight to stay alive.

Maggie realizes she’s part of some twisted social experiment—or perhaps a punishment.

This world feels like it’s built to break women through physical endurance, violence, and terror. But Maggie pushes through, becoming stronger, angrier, and more determined. She refuses to die for someone else’s story.

Part IV: All Together Now

Eventually, all three women awaken in a sterile, clinical facility. They learn they were participants (or victims) in an experimental system run by an entity named Mrs. C—a metaphorical, possibly literal representation of patriarchal authority.

Each woman was inserted into a simulation designed to test or “correct” them for perceived past misdeeds or non-conformity. These simulations played out genre archetypes that reflect societal expectations of women: nurturing mother, innocent girl, obedient survivor.

Instead of breaking, the women connect. They share their experiences, validate one another, and realize they’ve been intentionally manipulated. This unity becomes their power. Together, they rebel—rejecting the system, questioning its creators, and either escaping or beginning to dismantle it from within.

The story ends on a note of uncertain freedom, but one thing is clear: these women are done playing by the rules someone else wrote.

Characters

Celia

Celia’s journey is defined by her struggle to make sense of a life that feels completely foreign to her. She wakes up in a life she doesn’t remember, surrounded by people who claim to be her family, but she has no recollection of them.

As the story progresses, Celia starts to piece together the details of her life, including the fact that she runs an Italian restaurant and has a husband and daughter. However, everything around her feels unsettlingly fake.

Her initial confusion and disorientation give way to suspicion, as she begins to notice inconsistencies in her environment. Celia’s growth is marked by her increasing awareness of the artificiality of her life.

Her passive response to the events around her shifts toward active questioning, especially when she uncovers the body of Mrs. Corrigan. Her discovery of the murder forces her to confront the dark and sinister forces controlling her reality.

By the end of her arc, Celia becomes determined to uncover the truth. This marks a transition from confusion to resistance against the system that has manipulated her.

Allison

Allison’s character arc contrasts with Celia’s in that she is more immediately aware of the discrepancies in her life. She finds herself trapped in a high-school thriller scenario, with the stakes escalating through a series of violent events.

From the very beginning, Allison is more assertive in questioning her surroundings. She doesn’t accept the role of the passive victim in her life’s narrative, unlike Celia, who initially tries to blend in.

Allison is angry and suspicious, traits that push her to explore the artificial nature of her environment much sooner. As the violence intensifies and she uncovers more evidence of the manipulation of her world, Allison becomes increasingly proactive.

She is determined to assert her identity and fight against the forces trying to control her. Her arc is a journey from resistance to active rebellion, showing her growth from passive observance to a fierce desire to confront the system.

In the end, Allison embodies the character who, despite everything, refuses to accept her fate. She chooses to take action against the forces controlling her.

Maggie

Maggie’s arc is perhaps the most physically demanding of the three, as she is thrust into a dystopian wilderness that requires her to survive. Her world is brutal and unforgiving, filled with dangerous creatures and constant threats to her life.

Unlike Celia and Allison, who deal more with psychological manipulation, Maggie’s environment forces her to make primal survival decisions. Her growth is deeply tied to her ability to embrace her survival instincts and shed the fear that initially holds her back.

Maggie’s transformation is not only physical but emotional, as she grapples with guilt, anger, and a growing sense of agency. She becomes increasingly attuned to the way women are dehumanized and punished within societal structures, which is reflected in her resistance to the oppressive system controlling her.

As she grows stronger, Maggie not only learns to survive but also begins to question the system that has placed her in this brutal world. By the end of her arc, Maggie is no longer just a survivor; she is a leader, demanding the truth and the freedom she deserves.

Themes

A Study in Manipulation

One of the most prominent themes in Good Girls Don’t Die is the illusion of control, reinforced by the pervasive presence of surveillance. Each woman—Celia, Allison, and Maggie—exists in an environment where they are manipulated and observed by an unseen, authoritative force.

Their daily lives are constructed for them, with their actions and reactions monitored and evaluated. The lack of autonomy is central to their experiences, as they are forced to navigate scenarios where their free will is constantly in question.

This sense of being controlled without understanding the rules or the reasons behind the control creates an overwhelming tension. The women’s realizations that they are not living their own lives, but rather participating in a system designed to test or punish them, is a harrowing reminder of how surveillance can strip away personal identity and agency.

The theme explores the terrifying implications of a world where individuals are not only watched but also conditioned to behave in specific, prescribed ways. They are unable to escape the manipulation that surrounds them.

Reconstructing Identity in a World That Seeks to Erase It

In Good Girls Don’t Die, memory and identity are intricately connected to the characters’ struggles. The women experience varying degrees of amnesia or fabricated memories, which disorient them and heighten their sense of isolation.

Celia wakes up not knowing who she is or who the people around her are, while Allison and Maggie, too, face environments that force them to question their self-worth and the authenticity of their experiences. The manipulation of memory plays a significant role in stripping away their sense of self.

As each character fights to reclaim her identity, the narrative becomes a journey of self-discovery. For Celia, this involves piecing together fragmented memories, while Allison and Maggie must navigate their imposed roles within their respective genre-based environments.

This theme underscores the vulnerability that comes with losing control of one’s own history. It shows how easily an individual’s sense of self can be warped, erased, or replaced when external forces intervene.

The Subversion of Traditional Gender Roles Through Genre Conventions

The novel employs genre subversion to critique the societal roles assigned to women. These roles are often limited by society’s expectations or stereotypes, and the genre-based worlds each woman inhabits serve as metaphors for these constraints.

Celia’s cozy mystery setting anchors her in the role of a dutiful wife and mother, a stereotype she must break free from to discover the truth about her life. Allison’s high-school thriller environment thrusts her into the role of a teenage girl dealing with social drama and external threats, forcing her to navigate the pressures and dangers typical of YA fiction.

Maggie’s dystopian survival setting pits her against a ruthless world where she must fight for survival. This echoes the idea of women being forced into a battle for agency in a world that seeks to suppress them.

In each case, these genre frameworks highlight how women are often limited by predefined roles that society expects them to embody—whether as mothers, victims, or survivors. Each character must subvert these expectations to reclaim control over her fate.

Psychological Punishment and the Systemic Control of Women’s Bodies and Minds

Good Girls Don’t Die also addresses the theme of psychological punishment, particularly through how women’s bodies and minds are manipulated by a faceless, controlling entity. The experiences of Celia, Allison, and Maggie expose how societal systems seek to break down women psychologically and emotionally.

These systems not only constrain their physical freedom but also subjugate them mentally, forcing them into roles where their minds and bodies are dissected and molded according to an unseen authority’s will. The women are subjected to mental and physical trials designed to break them, testing their endurance, survival instincts, and resilience.

The narrative suggests that the social punishment of women often operates through psychological means. By putting the women in extreme, highly controlled situations that force them to confront their deepest fears and doubts, the story underscores the ways in which women’s identities and bodies have been historically controlled and punished by patriarchal forces.

This theme is not just a commentary on gender oppression but also a deep dive into the personal toll such systemic control can take on an individual. It highlights how psychological punishment plays a significant role in the dehumanization and disempowerment of women.

The Strength Found in Reclaiming Agency

In Good Girls Don’t Die, resistance is portrayed as a crucial form of empowerment for the female protagonists. As each woman uncovers the artificiality of her environment, she is faced with the choice to either accept her role and the constraints placed upon her or to fight back against the system that seeks to dominate her.

Resistance becomes a path toward self-empowerment, as each woman chooses to confront the reality around her and assert control over her future. Celia, Allison, and Maggie each demonstrate different forms of resistance—ranging from emotional and intellectual rebellion to physical survival.

Yet their actions all contribute to a larger theme of reclaiming their autonomy. By choosing to fight back against the system, the women break free from the roles and scenarios designed to subjugate them.

Their resistance is not just against the external forces controlling their lives but also against the internalized beliefs about their own worth and capabilities. This theme of resistance as empowerment underscores the importance of agency, self-determination, and solidarity among women in the face of overwhelming opposition.

Through their collective rebellion, the women come to understand that reclaiming their agency is not only a means of personal survival but also an act of defiance against the broader forces that seek to keep them powerless.

The Use of Genre as a Metafictional Commentary on the Construction of Women’s Roles in Literature

Lastly, Good Girls Don’t Die can be read as a metafictional commentary on the way literary genres shape the roles of women in fiction. The novel’s choice to place its characters in different genre scenarios—a cozy mystery, a YA thriller, and a dystopian survival narrative—serves as a critique of how women have historically been depicted in literature.

The cozy mystery genre, for instance, often centers around women in domestic roles, where their lives are seemingly perfect but ultimately filled with hidden dangers and secrets. The YA thriller genre is filled with teenage girls dealing with danger, romance, and identity crises, often portraying women as victims or survivors.

The dystopian genre typically focuses on female protagonists who must fight for their survival in harsh, unforgiving worlds. Through these genre lenses, the novel explores how these familiar tropes can limit the portrayal of women, reducing them to stereotypical roles that reinforce gendered expectations.

By deconstructing these genres, the book challenges the way women’s experiences have been framed in literature. It urges readers to reconsider the limitations placed on female characters and, by extension, real women in society.

The novel’s ultimate subversion of these genres calls for a reevaluation of how women’s roles are constructed in fiction. It critiques how such constructions can either empower or constrain them, depending on the narrative choices made by authors and society at large.