Good Grief Summary, Characters and Themes | Sara Goodman Confino

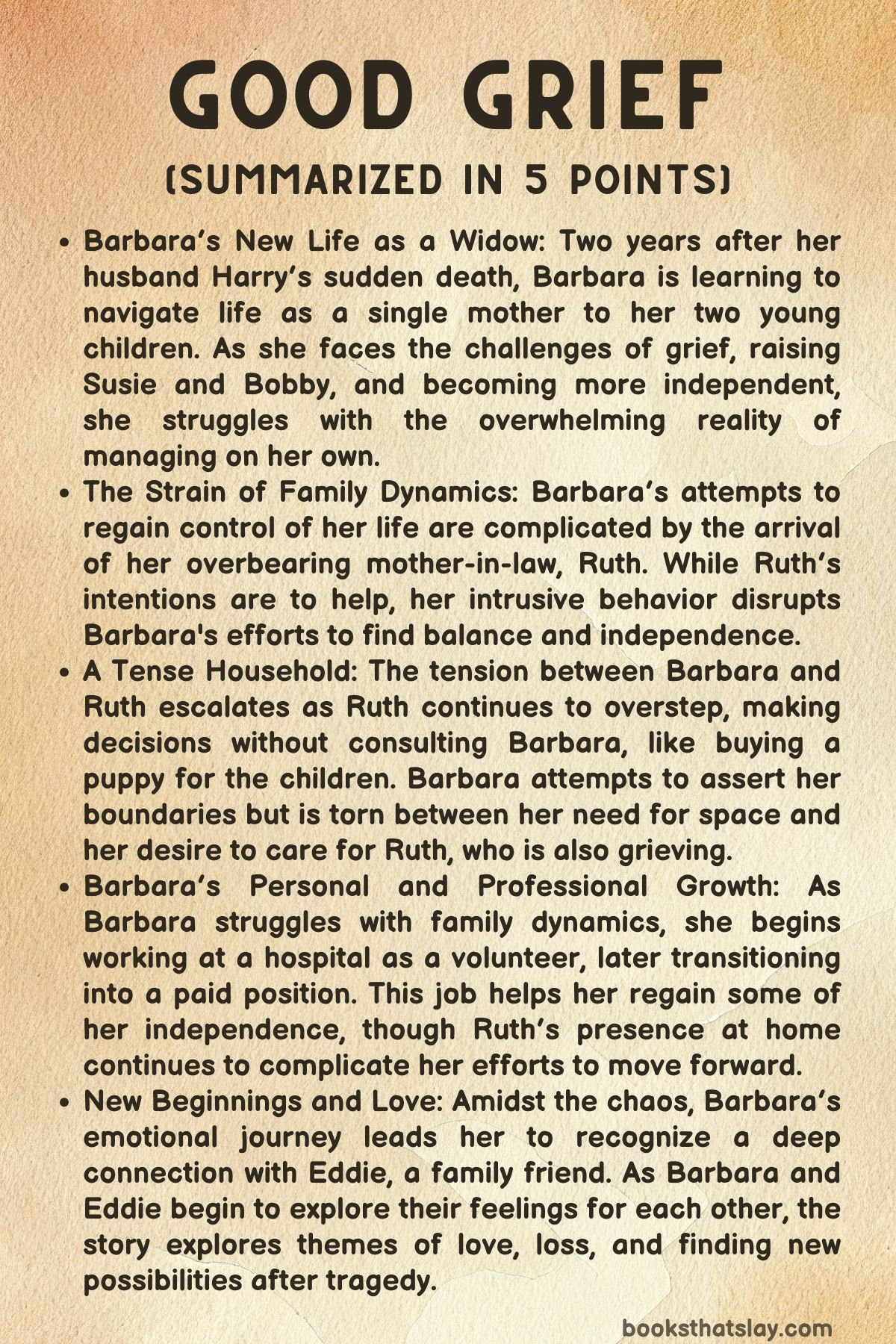

Good Grief by Sara Goodman Confino is a heartfelt exploration of loss, family, and the complexity of moving forward. The novel follows Barbara, a thirty-two-year-old widow, as she navigates life after the sudden death of her husband, Harry.

Raising two young children, Susie and Bobby, while grappling with grief and the challenge of independence, Barbara’s journey is marked by emotional turmoil, personal growth, and the tension created by her intrusive mother-in-law, Ruth. The book delicately addresses themes of widowhood, familial relationships, and the search for new beginnings, all wrapped in an honest portrayal of the messiness of life after loss.

Summary

Barbara’s life has been forever changed by the sudden death of her husband, Harry. At the age of thirty-two, she is left to raise their two young children, Susie and Bobby, while trying to find her footing in a world that seems to have moved on without her.

For the past two years, her mother had been living with her to provide support, but now that it’s time for her mother to return to Philadelphia, Barbara faces the daunting challenge of managing her household and the responsibilities of motherhood on her own. The thought of being alone is overwhelming, but she understands that this is the next step in her life.

Barbara feels the weight of Harry’s absence every day, but she does her best to provide a sense of normalcy for Susie and Bobby. The children cope with their grief in different ways.

Susie, at eight years old, has vivid memories of her father, while Bobby, who is six, has a more limited recollection. Barbara tries to make their lives as ordinary as possible, like treating them to ice cream for dinner to lift their spirits, though the sugar-induced sickness later reminds her that life is anything but ordinary.

As Barbara faces the day-to-day realities of single motherhood, she is struck by a sense of guilt and loss. She misses Harry deeply and questions whether she is capable of managing everything on her own.

Despite these feelings, Barbara knows she must continue, and over time, she starts to find a quiet resolve to keep going. Life may not be the same, but she will keep moving forward for her children’s sake.

One day, Barbara takes Susie and Bobby to the zoo, hoping to give them a break from their grief. The outing is bittersweet for Barbara, as it reminds her of the life they had when Harry was around, but she remains determined to create new memories.

However, the peace she begins to find is shattered when her mother-in-law, Ruth, unexpectedly arrives at the house with five suitcases, ready to stay indefinitely.

Ruth’s presence disrupts Barbara’s efforts to regain independence. A strict and controlling figure, Ruth had always been a dominant force in Harry’s life, and now she tries to impose her will on Barbara’s home.

While Barbara wants to assert her boundaries, she struggles with the guilt of pushing Ruth away, especially considering that Ruth, like Barbara, has lost someone dear to her. Ruth’s attempts to rearrange the furniture, criticize Barbara’s cooking, and involve herself in the children’s lives only add to Barbara’s frustration.

Despite her mounting frustration, Barbara remains patient with Ruth. However, Ruth’s behavior continues to create tension in the house, and Barbara begins to feel trapped.

In a bid to regain some control, Barbara takes on work at a local hospital, where she finds a sense of purpose and independence. Yet, Ruth’s overbearing presence still looms large, complicating Barbara’s attempts at normalcy.

Barbara’s life becomes a balancing act of managing her children, dealing with Ruth’s interference, and trying to rebuild her own sense of self. Ruth’s presence is a constant reminder of the past, and Barbara tries to navigate their strained relationship with care, even while feeling increasingly suffocated by it.

Barbara confides in her friend Janet about her frustrations with Ruth, and Janet humorously suggests that Barbara might need to marry Ruth off to get rid of her. Although Barbara isn’t keen on the idea, she begins to see that Ruth needs someone to care for her, just as Barbara needs to reclaim her independence.

Ruth’s loneliness becomes more apparent when Barbara discovers that Ruth has no place to go after losing her own home due to unpaid taxes.

As tensions rise, Barbara begins to devise a plan to help Ruth find companionship. She arranges for Ruth to meet Mr.

Moskowitz, a widower from their neighborhood, hoping that a new relationship might give Ruth a reason to leave. To Barbara’s surprise, Ruth and Mr.

Moskowitz form a bond, and over time, Ruth’s attitude softens. Though Barbara remains caught between her need for space and her desire to help Ruth, she begins to see a glimmer of hope.

Barbara’s life takes another dramatic turn when she returns to the hospital and finds herself embroiled in a strike led by the nurses in support of her wrongful termination. With the help of her friends, including Beverly, who is instrumental in organizing the strike, Barbara fights for her job.

After a tense negotiation, she is reinstated, but not without political maneuvering and a public confrontation with the hospital’s administrator, Dr. Harper.

The strike serves as a backdrop for Barbara’s ongoing struggles, reminding her that life, while full of setbacks, also offers opportunities for change and growth.

Throughout the story, Barbara grapples with her feelings of loneliness, especially as she grows closer to Eddie, a family friend who has been quietly in love with her. While Barbara is unsure of her ability to move on after Harry’s death, Eddie’s support provides a steady presence in her life.

As their relationship deepens, Barbara begins to recognize that love is possible again, even after loss. Meanwhile, Ruth also comes to terms with her own emotional wounds, and after some resistance, she begins to consider the possibility of a new relationship with Mr. Greene, a man who has been attentive to her needs.

By the end of the novel, Barbara’s emotional journey culminates in a sense of self-acceptance and healing. She realizes that while her life may not have unfolded as she had once imagined, it still holds the potential for new beginnings.

As she embraces the love and support of Eddie and her family, Barbara is finally able to move forward, finding hope in the possibilities that lie ahead. The story ends on a hopeful note, with Barbara ready to embrace the future, despite the challenges and losses that have shaped her past.

Characters

Barbara

Barbara is the central figure of Good Grief, a woman navigating the complexities of widowhood, motherhood, and the search for independence after her husband Harry’s death. At thirty-two, she finds herself facing life’s challenges with a quiet but determined strength.

She is dedicated to raising her two children, Susie and Bobby, while also managing the overwhelming responsibilities of running a household alone. The grief from losing Harry is something Barbara carries with her, often compounded by guilt as she tries to move forward without him.

Her internal struggles reflect her attempts to balance the needs of her children with her own emotional journey. Despite these challenges, Barbara demonstrates resilience, especially as she tries to regain her autonomy after her mother-in-law, Ruth, moves in.

While Barbara initially struggles with Ruth’s overbearing presence, she strives to maintain grace in the face of disruption, learning to assert herself over time. Her work at the hospital provides her with a sense of purpose, helping her reclaim a part of her identity outside of her role as a mother.

As the story progresses, Barbara comes to terms with the need for help, opening up to the possibility of love, particularly with Eddie, a family friend who becomes a source of emotional support. Her journey is one of self-discovery and finding balance amidst loss, guilt, and the complexities of family life.

Ruth

Ruth, Barbara’s mother-in-law, is a significant figure in Good Grief, embodying the struggles of a widow herself, as well as the difficulties of moving forward after the death of a loved one. After her son Harry’s passing, Ruth becomes a constant presence in Barbara’s life, though her attempts to help often cause more harm than good.

Ruth’s need for companionship and emotional connection often leads her to overstep her boundaries in Barbara’s home, from making unsolicited decisions about the children’s upbringing to disregarding Barbara’s wishes for how the household should be managed. Despite this, Ruth is not depicted as intentionally malicious but rather as a woman grappling with her own grief and loneliness.

Her desire to feel needed is evident, and she continuously seeks out ways to insert herself into Barbara’s life, even though her presence adds stress and tension. Ruth’s character arc is marked by her gradual transformation, particularly in her relationship with Mr.

Greene, a man from her past. Initially resistant to the idea of dating again, Ruth begins to soften as she receives attention from him.

This romantic subplot offers Ruth the opportunity to rediscover her own desires and sense of self-worth. Ruth’s growth throughout the novel is poignant, as she learns to confront her loneliness and reconsider what it means to move on after loss, providing Barbara with both an example of resilience and a challenge to her own path toward healing.

Susie

Susie, Barbara’s eight-year-old daughter, plays a vital role in Good Grief, representing the innocence of childhood intertwined with the complexity of grief. While Susie is too young to fully understand the depth of her father’s death, her memories of Harry are vivid and shape her emotional experiences.

Unlike her younger brother Bobby, who has only a faint recollection of his father, Susie carries a deep sense of loss and is often affected by her feelings of abandonment. As the family grapples with the absence of Harry, Susie’s reactions reveal the impact of grief on children and the way they process emotions in unique ways.

Her bond with her mother is strong, though it is often tested by the challenges Barbara faces in managing the household and coping with her own grief. Susie’s joy in moments of normalcy, such as her excitement over an ice cream dinner or a zoo outing, brings a sense of warmth and hope to the narrative, highlighting the importance of family connection and creating new memories in the face of loss.

Bobby

Bobby, Barbara’s six-year-old son, is another key figure in Good Grief, and his understanding of his father’s death is markedly different from Susie’s. While Susie holds onto memories of Harry, Bobby has only the faintest recollection of his father, which sometimes makes his grief more challenging to navigate.

Bobby’s innocence and naivety are often highlighted as he approaches the world with a simpler perspective. His relationship with Barbara is marked by his need for reassurance and love, and he serves as a reminder of the lighter moments in life, even in the midst of hardship.

Bobby’s character represents the emotional resilience of children who may not fully grasp the depth of loss but still feel its effects. His ability to move forward, despite his limited memory of Harry, contrasts with Susie’s deeper grief, providing Barbara with moments of clarity and understanding about how differently each member of the family processes their emotions.

Janet

Janet is one of Barbara’s closest friends and provides both comic relief and emotional support throughout Good Grief. As Barbara’s confidante, Janet offers a sounding board for her frustrations, particularly regarding the difficulties of living with Ruth.

Her humorous suggestions, such as the idea of marrying off Ruth to get her out of Barbara’s house, provide lighthearted moments in the otherwise heavy narrative. Despite her humor, Janet’s support is genuine, and she helps Barbara navigate the challenges of widowhood and motherhood.

Janet’s role as a friend is crucial to Barbara’s emotional journey, reminding her that even in the most difficult times, friendship and community provide a sense of belonging and support.

Eddie

Eddie, a family friend, becomes an important figure in Barbara’s emotional journey in Good Grief. His quiet affection for Barbara is apparent throughout the novel, though Barbara remains uncertain of her own feelings for him.

Eddie’s support during Barbara’s time of need is invaluable, and his presence in her life helps her gradually heal from the emotional wounds left by Harry’s death. As the story progresses, Eddie’s feelings for Barbara deepen, and his eventual confession of love marks a pivotal moment in her journey toward self-acceptance and healing.

Eddie represents the possibility of new love and emotional connection, offering Barbara hope that life can move forward, even after the loss of her husband.

Themes

Grief and Loss

In Good Grief, the theme of grief is deeply embedded in the story, portrayed through Barbara’s journey of coping with the sudden death of her husband, Harry. Barbara’s grief isn’t limited to a singular experience; rather, it manifests as an ongoing process of adjustment.

The author paints a realistic picture of how grief doesn’t follow a linear path, as Barbara wrestles with the emotional weight of loss while trying to maintain some semblance of normalcy for her children. Her grief is compounded by feelings of guilt for moving forward, especially in moments when she experiences small joys with her children or starts to regain her independence.

In these instances, Barbara is forced to reconcile the need to heal and the constant pull of her husband’s memory. The emotional turmoil Barbara faces, particularly at night when she lies in bed with her children, encapsulates the internal struggle of a widow: the tension between wanting to move on and feeling like doing so would dishonor the deceased.

Similarly, Susie and Bobby’s grief is also portrayed through their reactions to the absence of their father, each child processing the loss in their unique way. The novel paints grief as something that can’t be compartmentalized; it is a pervasive presence, a shadow that looms over all aspects of life, from the mundane to the deeply emotional.

Independence and Control

Barbara’s path toward reclaiming her independence is fraught with both internal and external struggles. The loss of Harry leaves her in a position where, for the first time, she is forced to navigate life on her own, raising two children without the support of her partner.

The complexities of independence are explored through Barbara’s desire to manage the household and her family without the assistance of her overbearing mother-in-law, Ruth. As Barbara begins to make decisions for herself and her children, such as treating them to ice cream for dinner or setting a routine, her need for control becomes evident.

However, Ruth’s presence continuously undermines this quest for autonomy. Ruth’s well-intentioned but intrusive actions—from buying a puppy for the children without Barbara’s consent to disrupting household routines—highlight the tension between Barbara’s desire for control and the reality of her circumstances.

In a broader sense, this theme touches on the idea that reclaiming control over one’s life after a major loss is not just a matter of independence, but of managing relationships and personal boundaries. Barbara’s struggle is not just to regain control of the household but also to preserve her sense of self amidst the well-meaning but stifling interference of others.

The novel explores how independence is not merely about physical autonomy, but also about emotional and psychological boundaries.

Family Dynamics and Relationships

The complexities of family relationships are central to the narrative of Good Grief, particularly in the way Barbara’s relationship with Ruth evolves. Ruth, a grieving widow herself, has her own set of needs, and her presence in Barbara’s home, though meant to help, complicates the already strained dynamics.

Barbara’s internal conflict is palpable as she balances her desire for space and independence with her empathy for Ruth’s loneliness and grief. Ruth’s interference in the daily lives of Barbara and her children often causes tension, yet there is also a deep sense of responsibility that Barbara feels toward her mother-in-law.

This complex relationship touches on themes of duty, sacrifice, and emotional exhaustion. Ruth’s resistance to moving on from the past is mirrored in Barbara’s own journey, suggesting that both women are trapped in different but related cycles of grief.

Despite their differences, they share an unspoken bond through their losses, and the gradual acceptance of each other’s role in the other’s life becomes an underlying narrative thread. As the story unfolds, Barbara learns to assert her own boundaries with Ruth, signaling a maturation in their relationship.

The theme of family dynamics is also present in Barbara’s evolving relationship with her children. As Barbara attempts to guide her children through their grief, she must also navigate the balance of being both a mother and a woman who is rebuilding her own life.

The novel portrays family not just as a source of love and support, but also as a complex web of interdependent roles that constantly shift in response to each individual’s personal growth.

Moving Forward and Second Chances

Throughout Good Grief, there is a strong undercurrent of hope and the possibility of new beginnings. Barbara’s journey, while marked by the overwhelming weight of loss, also reveals that life does not end with tragedy.

The emergence of potential new relationships, particularly Barbara’s evolving feelings for Eddie, underscores the theme of second chances. At the heart of this is Barbara’s realization that it is possible to love again, not in spite of her past, but alongside it.

Eddie, who has quietly been a source of support, eventually confesses his feelings for Barbara, and this moment marks a significant turning point in her emotional journey. However, Barbara’s hesitation to pursue this relationship highlights her struggle to reconcile her grief with the possibility of future happiness.

The story suggests that moving forward does not mean erasing the past, but rather integrating it into one’s new reality. Ruth, too, experiences a form of second chance as she begins to entertain the idea of a relationship with Mr.

Greene, someone from her past. This relationship, though complicated by Ruth’s own emotional resistance, shows that even in later stages of life, there is room for new experiences and connections.

The narrative challenges the notion that loss marks the end of one’s emotional growth, suggesting instead that it opens the door for transformation. For both Barbara and Ruth, second chances are not about forgetting the past but about allowing oneself to find new possibilities and embrace change with cautious optimism.

Guilt and Acceptance

Guilt plays a significant role in Good Grief, particularly in Barbara’s experience as a widow. The guilt she feels for moving forward, for starting to carve out a life without Harry, is a persistent emotional undercurrent throughout the novel.

She questions whether she is betraying Harry’s memory by embracing independence, joy, and even the possibility of love. This guilt is further complicated by her role as a mother—Barbara feels guilty for not being able to provide her children with the same family structure they had when Harry was alive.

As Barbara works through her internal conflict, she comes to understand that guilt, while a natural response to loss, cannot be the defining emotion that dictates her life. Her journey is not about absolution but about the acceptance of her circumstances and the realization that it is okay to move forward, even if it feels like an emotional betrayal.

Ruth, too, experiences guilt, particularly in her reluctance to pursue a relationship with Mr. Greene.

Her emotional resistance stems from her fear of forgetting her late husband, but as she begins to open up to the possibility of a new relationship, she confronts her own guilt and learns to let go of the past, allowing room for new connections. Ultimately, the novel reveals that guilt, while inevitable, should not paralyze a person from living.

Instead, accepting that life is not defined solely by loss but also by the capacity for renewal, is a vital step toward emotional healing.