Good Night, Irene Summary, Characters and Themes

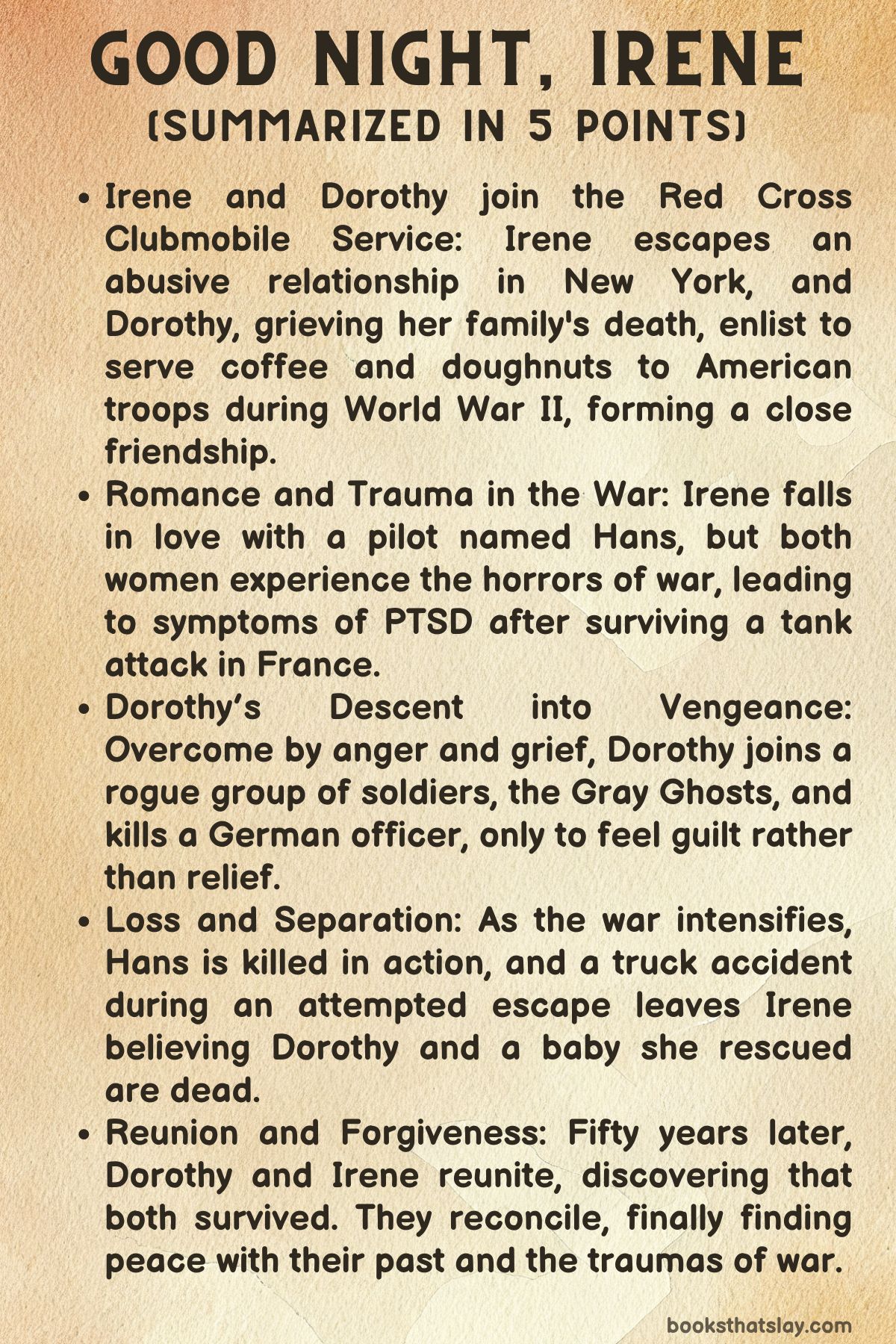

Good Night, Irene by Luis Alberto Urrea is a gripping historical novel set during World War II, based on the experiences of women who served in the Red Cross Clubmobile Service. The story follows two courageous women, Irene Woodward and Dorothy Dunford, as they drive to the front lines in Europe, serving coffee and doughnuts to soldiers to boost morale.

While navigating the horrors of war, they build a deep bond that is tested by personal trauma and loss. Inspired by Urrea’s mother, who was a Clubmobile volunteer, the novel captures the resilience of friendship and the lasting impact of war on those who serve.

Summary

Irene Woodward escapes her oppressive life in New York, leaving behind an abusive fiancé to join the Red Cross Clubmobile Service during World War II. Alongside other women, she embarks on a mission to drive trucks to the front lines, serving coffee and doughnuts to weary American soldiers.

During her training, Irene meets Dorothy Dunford, a young woman whose family has tragically passed away. The two form a fast friendship and are assigned to a Clubmobile named Rapid City.

After arriving in England, they begin their work on an Air Force base. There, Irene becomes romantically involved with a fighter pilot named Hans, providing a brief respite from the grim realities of war.

After D-Day, the Allied invasion of France, Irene is sent to assist in London, which is under attack by German bombers. In the aftermath of these raids, Irene begins showing signs of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), struggling with the devastation around her.

Hans helps her through this difficult time, but the trauma of war lingers. Reunited with Dorothy, the pair is transferred to France and later Belgium, following the relentless push of Allied forces.

As they work their way through war-torn Europe, the harshness of battle becomes impossible to ignore.

The two friends barely survive a tank attack that leaves them shaken. To recover from the physical and emotional toll, they are granted a short break in Cannes, where Irene and Hans rekindle their relationship and vow to reunite after the war.

However, tragedy strikes when Hans is killed during a mission, though Irene remains unaware. Meanwhile, Dorothy, consumed by the anger and loss of her family, takes drastic action.

She joins a rogue group of soldiers known as the Gray Ghosts, who conduct secret raids against German troops. Hoping to find closure, Dorothy kills a German officer, but instead, she feels only guilt.

Together, Irene and Dorothy witness the horrors of the Holocaust as they help soldiers liberate a concentration camp, further deepening their emotional scars.

Tensions rise when a soldier insults Irene, and Dorothy, quick to defend her friend, assaults him. Facing charges, Dorothy plans her escape with the help of the Gray Ghosts.

In a dramatic turn, Dorothy reveals that she has rescued a baby from the war-torn ruins, desperate to save its life.

Despite her misgivings, Irene agrees to drive her into the mountains, but disaster strikes when they hit a bomb crater. Their truck crashes, and while Irene is thrown clear, Dorothy and the baby are presumed dead.

Haunted by grief, Irene returns to the United States, believing she has lost her best friend.

Decades later, the truth comes to light when Dorothy, who survived the crash, visits Irene’s farm in New York. The two women, once thought lost to each other, share an emotional reunion, finding peace and forgiveness after all the pain and loss they endured.

Together, they reflect on their past, ready to move forward with the comfort of their enduring friendship.

Characters

Irene Woodward

Irene Woodward is the novel’s primary protagonist, a complex and resilient woman who embarks on a transformative journey. In the beginning, Irene is seen escaping a life of personal turmoil, leaving behind an abusive fiancé in New York.

This act of defiance and self-preservation marks her as a woman of courage who refuses to be victimized. Joining the Red Cross’s Clubmobile Service, she channels her desire for a fresh start into the meaningful, albeit dangerous, work of serving coffee and doughnuts to soldiers on the front lines of World War II.

Irene’s initial reasons for joining the service stem from a need for escape and reinvention. However, as the war progresses, her experiences in the field deepen her understanding of both the world and herself.

Irene’s relationship with Hans, a fighter pilot, shows her vulnerability and longing for human connection amidst the chaos of war. Her budding romance with Hans also exposes her to more emotional trauma, particularly when he dies in action.

Throughout her journey, Irene grapples with severe psychological stress, manifesting as symptoms of PTSD after enduring bombings and witnessing the horrors of the Holocaust. Her internal struggle with trauma becomes a major theme in her arc, but Irene also represents resilience.

She confronts the physical and emotional toll of the war and ultimately survives, returning to New York to live a life shaped by her experiences. The novel’s closing reunion with Dorothy brings her peace and suggests that, despite the scars left by the war, there is hope for healing and forgiveness.

Dorothy Dunford

Dorothy Dunford, or “Dot,” serves as Irene’s best friend and fellow Red Cross volunteer. Her character is defined by a deeper inner turmoil.

Dorothy’s backstory is marked by personal loss—her entire family is dead, leaving her emotionally adrift even before the war begins. She joins the Clubmobile Service not only to aid the war effort but also to escape her grief.

Dorothy’s character arc is heavily influenced by her anger and unresolved pain, particularly after witnessing the brutality of war firsthand. Her emotional journey is one of self-destruction and redemption, as she battles intense feelings of rage, especially after her family’s deaths.

Her turn towards violence, joining the clandestine group known as the Gray Ghosts, is a key turning point for Dorothy. This decision is driven by her desire to exact personal revenge on the enemy and to find a form of catharsis through violence.

However, this only leads to more guilt and psychological strain. Dorothy’s killing of a German officer reflects her descent into moral ambiguity and the consequences of allowing anger and grief to dictate her actions.

Her impulsive attack on Swede, another soldier, further demonstrates how her internal conflict manifests outwardly. Despite these missteps, Dorothy shows a compassionate side when she rescues a baby from the war zone.

This act of nurturing amidst chaos offers a glimpse into Dorothy’s deeper desire for connection and redemption. Her eventual reunion with Irene fifty years later highlights her capacity for survival and emotional reconciliation.

Dorothy, who had assumed Irene had died, is shocked to find her alive. Their reunion is cathartic for both women, allowing Dorothy to finally forgive herself and move forward from the past that haunted her for so long.

Hans

Hans is a fighter pilot and love interest to Irene. His presence in the novel serves a dual purpose.

On one level, Hans represents the fleeting and fragile nature of love and human connection during wartime. His relationship with Irene offers her a brief respite from the horrors of war.

Through their bond, Irene is allowed to experience moments of normalcy, affection, and hope for a future after the war. However, Hans’s role in the story is largely symbolic—his tragic death in the skies over Europe illustrates the personal losses that are an inevitable part of war.

Hans’s death triggers a further emotional spiral for Irene, who already struggles with PTSD. In losing Hans, Irene is forced to confront the futility and randomness of death in wartime, deepening her sense of existential despair.

Hans’s death is also significant in that it contributes to the novel’s broader theme of grief and loss. His absence echoes through the remainder of the novel, reminding both Irene and the reader of the costs of war, not only in terms of the lives lost but also the emotional devastation that lingers for the survivors.

Swede

Swede, a soldier whom Irene and Dorothy encounter in the aftermath of the war, represents a different kind of challenge for the women. When Swede insults Irene, Dorothy reacts violently, which results in severe consequences for her.

Swede’s role in the narrative is brief, but he serves as a kind of litmus test for Dorothy’s frayed mental state. The altercation with Swede reveals how close to the edge Dorothy is, struggling to maintain a sense of control amidst the emotional wreckage left by the war.

His character is not deeply developed but functions as a narrative device that forces Dorothy to confront her own behavior and the consequences of unchecked anger and violence.

The Baby

The baby Dorothy rescues near the end of the novel serves as a powerful symbol of hope, innocence, and the possibility of redemption. Amidst all the violence, destruction, and moral ambiguity, the baby represents a new life, untainted by the horrors of war.

For Dorothy, the baby is a way to atone for the violence she has committed and a chance to do something purely good. Her decision to save the child shows that even in the darkest times, acts of compassion and humanity can still arise.

The baby’s presence forces Dorothy and Irene to confront their own desires for redemption and healing. Even if Dorothy’s plan to escape with the child ultimately leads to disaster, the baby represents the potential for renewal.

The Gray Ghosts

Though not an individual character, the Gray Ghosts are a significant element in Dorothy’s narrative. This group of rogue soldiers operates outside the bounds of the official military chain of command, engaging in clandestine attacks on German forces.

Dorothy’s involvement with them represents her descent into a morally gray area where the lines between right and wrong are blurred by the raw emotions of anger and revenge. The Gray Ghosts symbolize the darker aspects of human nature that emerge in wartime.

Their inclusion in the story amplifies the novel’s exploration of moral complexity, particularly through Dorothy’s personal arc. They serve as a reminder of how war can distort ethical boundaries and push individuals to their breaking points.

Themes

The Trauma of War and Its Lingering Psychological Impact on Women in Non-Combat Roles

In Good Night, Irene, Luis Alberto Urrea explores the complex psychological effects of war on women who, though not soldiers, are constantly exposed to the horrors of the battlefield. Through the characters of Irene and Dorothy, the novel portrays the profound emotional and mental toll of war, showing how both women, despite being in a “morale-boosting” role, are left with deep psychological scars.

Irene’s post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) begins to manifest after witnessing the bombings in London, where her attempts to help victims ultimately leave her overwhelmed by the scale of destruction. This foreshadows the more intense psychological damage she will suffer later, especially after Hans’s death and the constant exposure to violence on the front lines.

Dorothy’s PTSD stems from both her personal tragedies and the moral complexities of war. The horrors of combat, the suffering of Holocaust victims, and her own acts of violence—such as killing the German officer—cause her to grapple with intense feelings of guilt and helplessness.

This theme emphasizes that trauma in war transcends the battlefield, affecting everyone involved, including those who are traditionally seen as non-combatants, such as the women of the Clubmobile Service.

The Erosion of Morality in War and the Search for Redemption Through Violence

One of the novel’s most compelling themes is the gradual erosion of moral boundaries in the face of extreme circumstances. Dorothy’s character arc poignantly illustrates how war can blur the line between righteousness and wrongdoing, as her initial sense of duty and honor morphs into a darker compulsion to seek retribution.

Dorothy’s decision to join the Gray Ghosts, a rogue group of soldiers conducting unsanctioned raids, marks her descent into moral ambiguity. Her belief that killing a German officer will provide closure for her family’s deaths represents a dangerous assumption that personal vengeance can coexist with the larger cause of justice.

After committing the act, she is left with only guilt, a stark realization that violence, no matter the justification, is corrosive. This exploration of morality within the chaos of war highlights the fragility of personal ethical codes when survival and anger collide.

Through Dorothy’s journey, Urrea suggests that acts of violence in war, even when committed with a sense of righteousness, lead not to redemption but to a deeper, more unsettling understanding of human nature and the futility of vengeance.

The Intersection of Gender, Duty, and Identity in the Wartime Experience

Urrea’s novel delves deeply into the unique challenges faced by women in war, focusing on the dual identities they are forced to navigate. The Clubmobile women are expected to maintain a traditionally feminine role—providing warmth, comfort, and companionship—while simultaneously confronting the grim realities of war typically reserved for male soldiers.

This intersection of gender and duty is a central tension for both Irene and Dorothy. They begin their service with relatively clear ideas about their roles but soon find those boundaries blurring.

Irene’s romantic involvement with Hans and her evolving sense of duty reflect a struggle to reconcile her personal desires with the expectations placed on her as a caregiver for the soldiers. Dorothy, on the other hand, experiences a more radical identity shift as she takes on roles traditionally associated with men, like joining the Gray Ghosts in combat missions.

This theme challenges the conventional wartime narrative by showcasing how women, even in auxiliary roles, are deeply affected by war. They are not just nurturers or bystanders but individuals forced to confront and redefine their sense of self amidst the devastation around them.

The Paradox of Survival and the Burden of the Past in Post-War Life

One of the most emotionally resonant themes of Good Night, Irene is the paradox of survival—the notion that those who live through war must grapple with the burden of memory, loss, and unresolved trauma long after the fighting ends. Both Irene and Dorothy survive the physical dangers of war, but the psychological wounds they carry into their post-war lives prove far more difficult to heal.

Irene’s deep depression after returning to the U.S. reflects how survival itself can be a haunting experience. The people she has lost and the horrors she has witnessed make it impossible for her to return to a “normal” life.

Similarly, Dorothy’s survival after the explosion—her belief that Irene has died and her own traumatic experiences with the Gray Ghosts—illustrates how surviving the war does not equate to emotional freedom. The novel’s conclusion, with the two women’s reunion fifty years later, symbolizes the possibility of reconciliation with the past, but it also underscores how the burden of survival extends across decades.

Urrea presents survival not as a triumphant endpoint but as a complicated, painful process of grappling with the past, loss, and guilt in order to achieve some semblance of peace.

The Illusion of Control in a World Governed by Random Chaos and Fate

Throughout the novel, the characters are repeatedly confronted with the unpredictability of war and the illusion of control in the face of overwhelming external forces. Irene and Dorothy, like many people during the war, initially believe they can exert some control over their circumstances—whether by volunteering for the Red Cross, choosing to form romantic connections, or even engaging in acts of rebellion like Dorothy’s participation with the Gray Ghosts.

However, the novel repeatedly subverts these expectations, showing that, in the grand scope of war, individual actions often do little to shape the broader, chaotic forces at play. Irene’s love for Hans and her efforts to protect herself and others ultimately cannot save him from being shot down by a German plane, nor can they shield her from the emotional devastation that follows.

Dorothy’s attempts to find closure through violence only lead to deeper disillusionment and more destruction. Even the final scene, with its emotional reunion, is tinged with the sense that both women were powerless to prevent the tragedies that befell them during the war.

This theme points to a broader existential reflection on how, despite human efforts to control or make sense of their lives, war exposes the limits of agency in a world where fate and chaos often hold sway.

The Role of Friendship as a Lifeline in the Dehumanizing Landscape of War

The friendship between Irene and Dorothy serves as the emotional core of Good Night, Irene, illustrating how personal bonds can provide essential emotional support in an otherwise dehumanizing environment. In a world where violence, loss, and despair constantly threaten to overwhelm the characters, the connection between the two women becomes their primary source of strength.

Urrea portrays their friendship as a dynamic and evolving relationship, one that deepens as they face shared traumas and emotional challenges. While their bond is initially formed out of circumstance—being assigned to the same Clubmobile—by the end of the novel, it is clear that their friendship has transcended mere companionship.

It becomes a crucial means of survival, not just physically, but emotionally and mentally. When Dorothy reveals the baby to Irene in the novel’s climax, the act underscores how their relationship is based on trust and shared responsibility, even in the most dire situations.

In the end, the reunion of the two women fifty years later suggests that the human connection forged in war can endure, offering hope and healing even in the face of immense suffering and loss.