Good Taste by Caroline Scott Summary, Characters and Themes

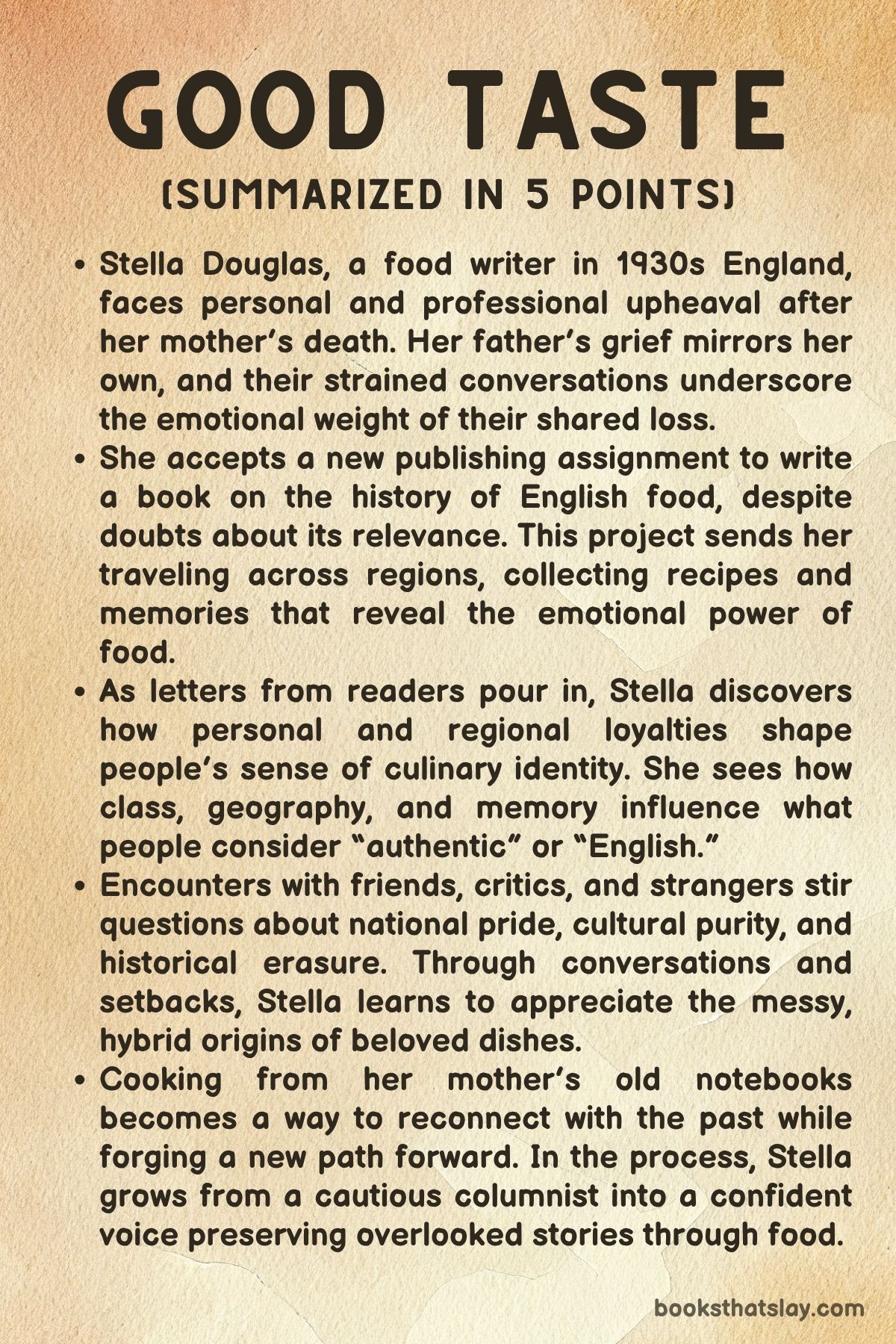

Good Taste by Caroline Scott is a poignant and quietly powerful novel set in 1930s England. At its heart is Stella Douglas, a food writer grappling with the recent loss of her mother, the changing expectations of her career, and questions about cultural identity.

When Stella is tasked with writing a book about English cuisine, her journey takes her beyond recipes into the kitchens, memories, and stories of everyday people. Through this exploration, she reflects on grief, belonging, and the meaning of “Englishness” in food.

The novel becomes both a personal and national history—intimate, humorous, and steeped in emotional depth.

Summary

Stella Douglas, a London-based food writer, is still reeling from her mother’s death. Seeking solitude and inspiration, she moves into a small, damp cottage in Yorkshire.

The change is not as romantic as she’d hoped—the cottage is cold, her father is still deeply withdrawn in his grief, and her own sense of purpose feels fragile. Her magazine columns have lost their spark, and her contract for a biography on Hannah Glasse is likely to be cancelled.

A visit to her publisher surprises her. Rather than letting her go, he proposes a new idea—a book called How the English Eat, a nostalgic history of English food meant for a broad audience.

Though hesitant, Stella accepts, unsure of how to define what “English” food really is. She begins her research by placing ads in regional newspapers, asking readers to send in traditional family recipes.

Soon, her mailbox is overflowing with letters, each one revealing not just dishes, but fragments of personal histories. Stella starts mapping responses and travelling to meet the people behind the recipes.

Along the way, she discovers the diversity of regional cooking and the strong emotions tied to memory and taste. She becomes fascinated by how names for the same food differ across counties, how class affects what people eat, and how war and hardship have shaped domestic kitchens.

Her personal life remains complicated. A visit to her close friend Michael brings her into awkward proximity with Lucien, Michael’s partner, who mocks her work and the very idea of English cuisine.

Stella wrestles with doubt. Is she compiling something meaningful, or just curating sentimental anecdotes?

She wonders whether a nation’s food identity can ever be separated from outside influences. She questions whether even nostalgia is a kind of myth-making.

In the midst of this questioning, her research takes on deeper emotional significance. She revisits her mother’s handwritten recipe books, triggering vivid memories of meals shared and stories told.

Cooking those recipes reconnects her with her past and rekindles her commitment to the book. Each letter she receives starts to feel like a thread in a larger fabric of memory and resilience.

She hears from women who’ve used food as a way to pass down identity or reclaim lost moments. Stella’s writing evolves.

She no longer pretends food is just about ingredients. It’s about ritual, comfort, history, and emotion.

Her project becomes more candid and less polished. This honesty resonates with readers.

Despite a few kitchen disasters—like a failed dinner party featuring historical recipes—she learns to embrace imperfection and laughter. Her bond with Michael remains tender but unresolved.

They share an emotional intimacy that isn’t romantic but still runs deep. She begins to see that not all relationships require traditional outcomes to be meaningful.

As the book nears completion, Stella reflects on how far she’s come—not only in her research, but in her own emotional life. She delivers the manuscript with both pride and fear.

It’s not just a food history—it’s a tribute to memory, place, and the unseen lives of ordinary people. Returning home, Stella and her father prepare one of her mother’s recipes together.

The act of cooking bridges the silence between them, allowing space for healing. With spring approaching, Stella senses a quiet renewal.

She no longer sees herself as just a food writer. She sees herself as someone capable of giving voice to stories that matter.

By the end, Good Taste becomes more than the story of one woman’s professional challenge. It is a gentle meditation on how food connects us to the past, to each other, and ultimately, to ourselves.

Characters

Stella Douglas

Stella is the novel’s central figure, and her journey is both external—across England gathering recipes—and internal, as she navigates grief, creative doubt, and questions of cultural identity. Following the death of her mother, Stella finds herself emotionally unmoored.

Her move to a damp Yorkshire cottage symbolizes a bid for independence and renewal, though it often emphasizes her isolation. As a food writer, she initially performs a cheery persona for her column, masking her disconnection from joy.

The project she embarks upon—writing How the English Eat—begins as a nostalgic commission but evolves into something deeply personal. Stella’s growing archive of recipes and letters becomes a mirror for her own exploration of memory, heritage, and loss.

Her transformation unfolds gradually: from self-doubt and imposter syndrome to a recognition that storytelling, especially about food, can be a profound act of preservation and healing. By the end, Stella emerges not only as a writer of merit but as someone who reclaims her voice and familial past with grace and insight.

Stella’s Father

Stella’s father is portrayed as a quiet, emotionally reserved man still mourning his wife’s death. Their early interactions are tentative, marked by restrained affection and unspoken grief.

He struggles with loneliness and nostalgia, his life a series of small rituals haunted by memory. Yet as Stella delves into her culinary research, their bond subtly strengthens.

Cooking together in the final chapters marks a significant emotional shift—an act of reconnection that bridges the generational and emotional gap between them. He serves as a grounding presence, reminding Stella of the emotional depth behind seemingly simple domestic acts like making breakfast or baking familiar recipes.

Michael

Michael is Stella’s long-time friend and emotional confidant. Warm, witty, and affectionate, he provides a touchstone of familiarity in her otherwise shifting world.

His relationship with Cynthia Palmer creates an undercurrent of tension—Stella’s jealousy remains mostly unspoken, but it adds complexity to their dynamic. Michael is both supportive and elusive.

He does not fully understand the depth of Stella’s project, but he appreciates her commitment and emotional vulnerability. Their bond is intimate, though never romantic in a sustained way.

By the novel’s end, their connection resembles a kind of chosen kinship—rooted in shared history and mutual care, even as their futures diverge.

Lucien

Lucien, Michael’s partner, is initially presented as critical, snide, and dismissive—particularly of Stella’s work and of English culinary tradition more broadly. His disdain seems to encapsulate a broader skepticism of nostalgia and nationalism.

However, as the narrative progresses, Lucien is revealed to be more complex. His hostility masks a deeper insecurity and emotional wound, perhaps tied to his own relationship with heritage and belonging.

In a key confrontation, he exposes his personal vulnerability, allowing Stella—and the reader—to see his criticisms as a form of self-protection rather than malice. Lucien ultimately challenges Stella to think more rigorously about the politics of food, even as their values diverge.

Dilys

Dilys is Stella’s eccentric neighbor and an emblem of wisdom on the margins. With unconventional views and a sharp tongue, she plays a vital role in nudging Stella out of self-pity and toward greater introspection.

Dilys is not sentimental; instead, she questions assumptions and provides philosophical provocations. Her encouragement to consider the wider cultural implications of Stella’s work, especially around authenticity, nationalism, and memory, makes her a quiet but important intellectual influence.

Through Dilys, Stella begins to understand that the emotional, political, and historical threads of food are inseparable. She realizes that writing about cuisine is never just about recipes.

Cynthia Palmer

Cynthia is a glamorous and socially confident woman involved with Michael. Though she never becomes a central character, her presence looms over Stella’s emotional journey.

Cynthia represents everything Stella is not—stylish, assertive, and comfortably situated within modern social circles. This contrast underscores Stella’s internal struggle with confidence and belonging.

Stella’s mixed feelings about Cynthia—envy, irritation, curiosity—highlight the subtle tensions of gender and societal expectations. Cynthia’s role, though peripheral, catalyzes Stella’s reflection on her desires and limitations.

The Letter Writers and Recipe Contributors

Though unnamed and often appearing only briefly, the people who respond to Stella’s newspaper appeals form a kind of collective character—an oral and emotional history of England told through food. Their letters offer a patchwork of lived experience: rationing during wartime, family feasts, passed-down methods of preserving fruit or baking bread.

Each submission is laced with memory and personal truth, often revealing more about loss, joy, and survival than about the recipes themselves. Through these correspondents, the novel constructs a vibrant mosaic of English identity—one that transcends region, class, and gender.

They remind Stella (and the reader) that history is not confined to archives; it lives in kitchens and memory. Their voices expand the scope of Good Taste, making it not just Stella’s story, but a shared national and emotional narrative.

Themes

Grief and Emotional Inheritance

At the emotional core of Good Taste lies Stella’s experience of grief following her mother’s death. Her sorrow is not loud or melodramatic but is instead quietly threaded through her daily actions, her reflections, and her choices.

Stella’s grief shapes how she sees the world and herself, coloring her understanding of the past and her vision for the future. Her attempts to connect with her late mother—through her handwritten cookbooks, favorite recipes, and remembered kitchen rituals—reveal how mourning can become a lifelong dialogue rather than a process with a neat endpoint.

The preparation of food becomes an act of remembrance and intimacy, allowing Stella to feel the presence of her mother in tactile, sensory ways. This deep emotional inheritance blurs the line between memory and identity, with every dish prepared becoming a form of communion with the past.

Grief here is not a solitary burden; it becomes a medium through which Stella forges emotional meaning. Eventually, she learns that honoring the past does not mean living in it.

The kitchen, which once symbolized loss, transforms into a space for healing and quiet continuity.

Cultural Identity and Englishness

The novel repeatedly questions what it means for something to be “English,” especially in relation to food. Stella’s commission to write How the English Eat pushes her to confront the assumptions, contradictions, and complexities wrapped up in that phrase.

English cuisine, as she discovers, is a record of invasions, migrations, and borrowings—foreign ingredients made domestic through centuries of adaptation. The diversity of dishes, dialects, and regional preferences makes it clear that there is no single, pure version of English food.

Instead, what exists is a fragmented and richly varied collection of tastes and traditions, each deeply personal yet often mythologized as national heritage. Stella’s struggle to reconcile nostalgia with historical accuracy becomes a reflection of broader tensions around national identity in the interwar period.

Her growing awareness that patriotism can distort memory leads her to reject simplistic narratives. The question of Englishness is answered not through patriotic certainty but through humility and curiosity.

The book she writes ultimately embraces the multiplicity of England, allowing food to be both a cultural artifact and a living expression of regional voices, immigrant influences, and personal stories.

Gender, Labor, and Authorship

Good Taste explores how women’s work—particularly in domestic and culinary spaces—has been historically marginalized, even though it is foundational to cultural memory. Stella’s research for her book leads her to women whose recipes have been passed down like oral history, carried not in print but in hands and hearts.

These women, often overlooked in traditional historical narratives, emerge as custodians of a different kind of knowledge. Their food is not just sustenance but storytelling, resistance, and identity.

Stella’s own position as a female food writer navigating a male-dominated publishing world reflects the limited spaces in which women were allowed to claim intellectual authority during the 1930s. Her decision to document these domestic narratives represents a form of feminist reclamation.

She begins to see food writing not as frivolous or secondary, but as a legitimate form of authorship—one that gives voice to women who have long been denied historical recognition. The act of assembling recipes becomes a literary project, and Stella’s role evolves from passive observer to intentional chronicler.

Her voice, once timid and uncertain, gains clarity and conviction as she begins to understand that the personal is political. Domestic labor, long dismissed as mere routine, is shown to be rich with cultural and historical meaning.

Memory, Nostalgia, and the Unreliable Past

Throughout Good Taste, memory functions both as a guide and a trickster. Many of the people Stella interviews are convinced their recollections of food are factual and absolute, but she quickly realizes that memory is colored by longing, loss, and idealization.

Recipes are rarely just instructions—they are encoded with emotion, marked by the presence or absence of loved ones, and shaped by the times in which they were made. As Stella collects stories and ingredients, she begins to understand that nostalgia is not merely a yearning for the past but a reconstruction of it.

It can comfort, but it can also obscure. This is particularly evident in the tension between historical accuracy and the “warm, accessible” tone her publisher demands. Stella finds herself at a crossroads: does she write the truth, with all its complexities and contradictions, or does she offer a sanitized, comforting version of history?

Ultimately, the novel argues that memory and nostalgia can be valid forms of truth—not because they are factual, but because they are emotionally honest. The past may be imperfect, but the feelings it inspires are real.

Stella’s book, in the end, becomes a tribute not just to what people ate, but to how they remembered eating it.

Class, Region, and Social Distance

Class differences simmer beneath the surface of nearly every interaction Stella has during her research. From London’s literary circles to Yorkshire’s kitchens and market stalls, the contrast in speech, taste, and cultural assumptions is pronounced.

Food becomes a marker of class distinction—what one eats, how it is prepared, and how it is spoken about can instantly reveal one’s social position. The North-South divide is particularly salient, with Northern food traditions often characterized as frugal, honest, and plain, while Southern dishes are described as more indulgent and refined.

But as Stella travels and listens, these stereotypes begin to erode. She discovers pride and innovation in the most modest kitchens, as well as snobbery and ignorance among the educated elite.

The diversity of her correspondents—farmers, housewives, shopkeepers—expands her understanding of English food as a democratic archive. It resists elitist categorization.

These encounters challenge Stella’s own biases and help her to write a book that is not just about heritage but about inclusivity. The final product speaks not to a monolithic culture but to a nation made up of many voices, each shaped by economic circumstance and regional experience.

In doing so, the novel gently critiques the class system while celebrating the dignity and richness of working-class life.