Grace and Henry’s Holiday Movie Marathon Summary, Characters and Themes

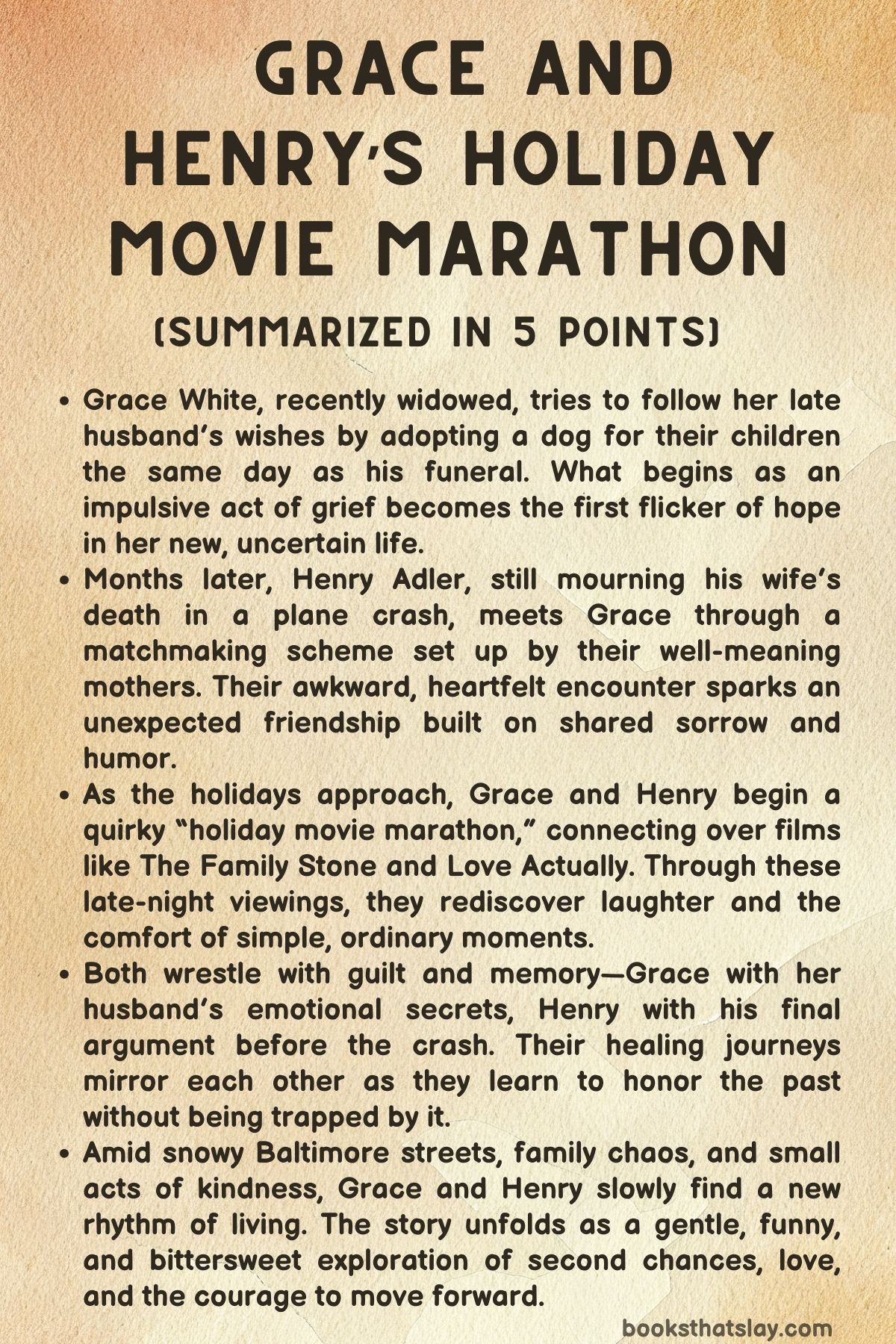

Grace and Henry’s Holiday Movie Marathon by Matthew Norman is a tender and humorous exploration of grief, healing, and unexpected second chances. The novel follows two widowed strangers—Grace White, who recently lost her husband Tim, and Henry Adler, mourning his wife Brynn after a tragic plane crash—as their paths cross in Baltimore during the holiday season.

Both are struggling to rediscover meaning amid loss, trying to raise children, manage loneliness, and find laughter again. Through shared memories, awkward encounters, and a mutual love of movies, they learn that even in the aftermath of heartbreak, it’s possible to build something new, imperfect, and real.

Summary

Grace White’s story begins on the day of her husband Tim’s funeral. Still wearing black, she drives with her two children, Ian and Bella, to the Maryland SPCA to adopt a dog—a plan that had been part of Tim’s carefully prepared “after I’m gone” checklist.

Tim had wanted his family to find joy amid sorrow, to bring warmth back into their lives. At the shelter, Grace and her children meet a shy black-and-white puppy abandoned at the door.

Bella names him Harry Styles, and for the first time since Tim’s passing, Grace feels something resembling hope.

Months later, Henry Adler enters the story. He’s a widower too, an ad executive still reeling from the sudden death of his wife Brynn in a plane crash.

Henry spends weekends at his parents’ Baltimore home, avoiding his apartment and any reminder of life before loss. His parents and Grace’s mother, Maryellen, conspire to set them up under the guise of fixing a Wi-Fi problem.

When Henry visits, Grace immediately sees through the ruse, and they share a moment of awkward laughter. Both recognize in each other the rawness of fresh grief, and what begins as an uncomfortable setup turns into an unexpected friendship.

As winter deepens, Grace and Henry navigate the holidays separately but with parallel emotions. Grace’s family Thanksgiving is chaotic and overbearing, while Henry’s is awkwardly cheerful.

Each quietly thinks of the other that night. Days later, a spontaneous text from Henry turns into a long, easy conversation filled with humor and mutual understanding.

They bond over their shared cynicism about holiday movies and decide to “hate-watch” The Family Stone together. When they meet at Grace’s house, the night unfolds naturally, the children warm to Henry, and Grace feels an unfamiliar calm around him.

Their movie night ends in laughter, interrupted only by a chaotic discovery of mice in the kitchen—an absurd, joyful moment that bridges grief and ordinary life.

Their friendship deepens. Henry becomes close to Grace’s son Ian, encouraging his love for art and taking him and Bella to the Walters Art Museum.

Grace begins to laugh more, work more passionately at her bar, Edgar Allan’s, and enjoy the presence of her children and friends again. Yet beneath the surface, both still wrestle with guilt—Henry over Brynn’s death, Grace over her loyalty to Tim’s memory.

During a quiet conversation, Grace tells Henry that after Tim’s slow death from cancer, she learned to treasure small, everyday details. Henry confides that he never got to say goodbye properly.

His last memory of Brynn was an argument over her work trip—the same one that ended in the crash. He secretly believes his stubbornness sent her to her death, a thought that has consumed him ever since.

Their bond grows through movie nights, texts, and shared humor. One evening, while both watch Edward Scissorhands alone, Grace impulsively invites Henry over.

The night is charged with emotion and attraction, yet neither can move forward. When Grace retreats to gather herself, she imagines Tim’s presence, frail but tender, silently questioning her readiness to love again.

Later, a text from Meredith, a woman Henry’s brother had introduced him to, flashes on his phone. Grace insists he meet Meredith, saying it’s the kind thing to do, even as she feels conflicted.

Henry’s date with Meredith is unexpectedly pleasant—she’s funny and self-assured—but even as they talk and dance, Grace lingers in his mind. That night, he calls Grace, confessing that Meredith kissed him.

Their conversation is honest and bittersweet: Grace encourages him to let good things happen again, even as she realizes she might be falling for him.

A turning point comes when Henry suffers a minor accident while fixing a light fixture. He’s knocked unconscious and experiences what feels like an encounter with Brynn in a liminal space.

She appears calm and loving, urging him to stop punishing himself. She tells him that she chose that flight, that he wasn’t to blame, and that it’s okay to love someone else.

Before fading, Brynn tells Henry to think of Grace—because she could love him too.

Meanwhile, Grace faces her own reckoning. She discovers emails between Tim and a colleague, Lauren Maxwell, suggesting an emotional affair before his death.

Though there was no physical betrayal, the intimacy devastates her. She decides to meet Lauren, who admits to loving Tim but confirms he chose Grace and the children.

The truth, though painful, allows Grace to see her marriage more clearly: imperfect, but rooted in love.

Henry visits Grace afterward, nervous and still bandaged from his accident. He brings an old gaming console for the kids, a gesture that wins their delight.

Alone with Grace, he blurts out that he wants to take her on a date. She’s startled—especially since she knows he’s supposed to move to Los Angeles—and deflects, saying they’re both too broken.

Henry, hurt but understanding, leaves quietly.

Days later, as Baltimore prepares for Christmas, Henry contemplates leaving but feels an ache he can’t ignore. Grace attends her children’s school holiday assembly, where Ian wins an art contest inspired by Henry’s encouragement.

When Henry receives a photo of Ian holding his ribbon, he breaks down, realizing how much they’ve come to mean to him.

On Christmas Eve, Grace learns from her mother that Henry has been keeping her rescued mice safe in his own house for the winter. Moved by his kindness, she gathers her family—children, parents, and siblings—and together they walk through the snow to his house.

When Henry opens the door, she tells him she came to kiss him, and he kisses her first as their families cheer and the snow falls softly around them.

The novel closes months later, with spring bringing renewal. Henry has decided not to move to Los Angeles.

He and Grace are now a couple, building a life that honors their pasts without being defined by them. Together, they release the mice into the grass near a creek, a symbolic act of letting go.

Watching them disappear, they hold hands, accepting that while they can’t control what lies ahead, they can choose to move forward—together, with hope.

Characters

Grace White

Grace White serves as the emotional anchor of Grace and Henry’s Holiday Movie Marathon, a woman defined by resilience and quiet strength. Newly widowed, she faces the unbearable void left by her husband Tim’s death with both determination and confusion.

From the moment she drives to the SPCA in her funeral clothes, Grace’s grief manifests not in paralysis but in restless motion—a need to act, to rebuild, to follow the plans Tim meticulously left behind. Yet beneath her composure lies an aching vulnerability.

Her decision to adopt a dog, her fumbling attempts to reassure her children, and her dark humor reveal a woman balancing the absurdity and agony of loss.

As the story unfolds, Grace’s grief evolves from numb practicality to a deeper confrontation with loneliness, guilt, and rediscovered desire. Her imagined conversations with Tim—part ghostly, part psychological—illustrate her struggle to let go while still honoring the love they shared.

She oscillates between tenderness and exasperation, between laughing at her own pain and succumbing to it. Her connection with Henry Adler emerges not from romance but from mutual recognition; both are wounded, searching for meaning amid grief.

Grace’s growth lies in learning that moving forward does not mean betraying the past. By the novel’s end, she embodies hope—not because she stops grieving, but because she learns to live with her loss without being defined by it.

Henry Adler

Henry Adler is a man paralyzed by guilt and memory. A talented advertising professional whose wife Brynn died in a plane crash, he is haunted not only by her death but by the bitter argument that preceded it.

His grief is steeped in self-blame—an irrational belief that his behavior drove Brynn onto that doomed flight. This emotional self-punishment isolates him, making him unable to inhabit his own life.

Henry’s personality is marked by sarcasm and awkwardness; he hides his pain behind quips and social discomfort. Yet beneath this lies genuine sensitivity, evident in his patient rapport with Grace’s children and his appreciation for art and emotional honesty.

Henry’s arc mirrors Grace’s, but his path is darker and more internal. His imagined encounter with Brynn after being electrocuted is a pivotal moment of reconciliation.

In that surreal, redemptive scene, Henry confronts his guilt, receives forgiveness, and is finally released from the prison of “what-ifs.” His later courage to ask Grace out reflects a newfound willingness to risk living again. By choosing to stay in Baltimore rather than escape to Los Angeles, Henry affirms that love after loss does not erase old love—it continues it.

He grows from a man trapped in regret to one capable of embracing the unpredictable, messy beauty of a second chance.

Tim White

Though Tim White dies before the story begins, his presence permeates every page. Through Grace’s memories and imagined conversations, he emerges as a man of humor, foresight, and deep affection—a planner who even in death sought to protect his family.

His “When I’m Gone” sessions, complete with printed agendas, reflect both his pragmatism and his need to ease the blow of his departure. Yet later revelations about his emotional connection with a colleague, Lauren Maxwell, complicate his legacy.

Tim becomes more human—flawed, loving, and fallible.

Tim’s lasting influence shapes Grace’s every decision. He represents both the love she can’t relinquish and the emotional weight she must eventually set down.

Even in her imagination, Tim continues to guide and tease her, reminding her that life must go on. His character thus bridges past and present, death and renewal.

Through him, the novel explores how memory can comfort and confine, how love can linger even when it hurts.

Brynn Adler

Brynn Adler, though physically absent, remains the emotional compass of Henry’s story. In life, she was intelligent, composed, and quietly humorous—a stabilizing presence to Henry’s restlessness.

Her death fractures him, but her spectral reappearance during his near-death experience offers both closure and transcendence. Unlike Tim’s lingering shadow in Grace’s life, Brynn’s visitation provides active guidance, urging Henry to embrace the possibility of new love.

Brynn’s character illustrates the idea that love after death can still be generous. Her forgiveness and reassurance that she chose her path free Henry from his paralyzing guilt.

She is a symbol of acceptance, her calmness contrasting with Henry’s emotional turmoil. In the end, Brynn’s legacy is not tragedy but release—she enables Henry to move toward Grace without the burden of betrayal.

Ian White

Ian, Grace and Tim’s ten-year-old son, embodies innocence and artistic sensitivity. Through his eyes, grief becomes something both literal and profound; he channels his emotions into art, drawing pictures that reflect the family’s fragile hope.

His fascination with creativity connects him deeply to Henry, whose mentorship becomes both healing and transformative. Ian’s empathy—his refusal to kill the mice because “they know what death means”—underscores the story’s recurring theme of compassion amid loss.

Ian’s triumph in the school art contest signifies more than talent; it symbolizes renewal, the continuation of love through imagination. His growing bond with Henry acts as a bridge between past and future, between memory and the promise of something new.

Bella White

Bella, Grace’s six-year-old daughter, represents the purest form of resilience. Her questions about heaven, her affection for their dog Harry Styles, and her matter-of-fact wisdom inject moments of light into the narrative’s heaviness.

She embodies a child’s way of grieving—direct, fleeting, and full of wonder. Bella’s interactions often remind the adults that healing doesn’t always come from understanding but from simply living.

Her presence gives the story warmth, innocence, and humor, grounding the emotional weight of her mother’s and Henry’s journeys.

Dom

Dom, Grace’s friend and fellow restaurateur, stands as a subtle representation of stability and unspoken affection. His easy camaraderie with Grace, his humor, and his enduring crush on her add a layer of human warmth to the story.

Dom’s presence reminds both Grace and the reader that love need not always be grand or dramatic—it can exist quietly, waiting to be noticed. He also contrasts Henry’s emotional vulnerability with grounded pragmatism, reflecting different ways of coping with loneliness.

Lauren Maxwell

Lauren Maxwell’s character introduces moral complexity. As Tim’s emotional confidante, she forces Grace—and the reader—to confront uncomfortable truths about fidelity and love.

Her confession that she loved Tim but respected his choice to stay loyal reframes Grace’s understanding of her marriage. Lauren is not a villain but a mirror, showing Grace that love can exist in multiple, conflicting forms.

Through their painful yet cathartic conversation, Grace achieves the closure she never realized she needed.

Themes

Grief as a Continuing Relationship with the Dead

Grace and Henry’s experiences of loss in Grace and Henrys Holiday Movie Marathon are not framed as problems to be solved but as ongoing relationships with the dead that must be carried forward. Grace has already said goodbye to Tim in a hundred small ways during his illness, so after his death she is less interested in big, dramatic speeches than in telling him the tiny details of her day: the small irritations, the funny moments with the kids, what she watched on TV.

Those casual, domestic updates preserve the feeling that he is still her partner in the ordinary business of life. Henry, by contrast, is trapped inside the last bad morning he had with Brynn and feels that his whole relationship has been reduced to that moment.

Where Grace’s grief is about keeping a conversation going, his is about being unable to get past a single unfinished sentence. The story repeatedly shows them “talking” to their dead spouses, whether in imagined conversations in a closet or bathroom mirror, or in Henry’s near-death encounter where Brynn appears beside him, still observant, still knowing his habits, still loving him enough to push him back toward the living.

The tone around these moments is strikingly matter-of-fact. There is no horror or melodrama when Tim appears in Grace’s reflection, or when Brynn sits cross-legged near Henry’s bleeding body; the narrative treats these encounters as extensions of the emotional reality they are already living.

That choice suggests that grief is not the severing of a tie but a reconfiguration of it. The dead are still participants in decisions about romance, parenting, and self-forgiveness.

Grace hesitates to kiss Henry because, in her mind, she must consider Tim’s feelings; Brynn gently argues for Henry’s future with Grace precisely because she loves him and knows she cannot accompany him any further. The novel honors the way bereaved people often carry their dead as internal companions, letting those remembered voices argue, joke, and advise.

Grief here is less about saying farewell once and for all and more about learning how to share your head and heart with someone who is gone while still finding room for what comes next.

Love After Loss and the Risk of Beginning Again

Romantic love after widowhood arrives in this story not as a sweeping rescue but as something tentative, awkward, and morally complicated. Grace and Henry are both convinced early on that they are “sexually dead inside,” and they half-protect, half-punish themselves with that belief.

Grace jokes about her body being in hibernation, hiding a deep fear that wanting someone else will erase Tim or mark her as disloyal. Henry carries an almost sacred image of Brynn that makes the idea of kissing another woman feel like vandalizing a cherished memory.

Their early flirtations—texting about “booty texts,” drinking beers by a backyard fire, watching holiday movies together—are deliberately low-stakes, wrapped in humor so that neither has to say out loud that they are feeling something unfamiliar and frightening: attraction that does not cancel out their grief.

The story insists that beginning again is not a simple line from “sad” to “happy” but a messy Venn diagram where old love and new love overlap. Henry’s date with Meredith shows this clearly.

On paper, she fits the life he had with Brynn: tall, polished, bookish, good at performing in public. The small, slightly clumsy kiss outside the bar is a milestone—proof that his body and heart can respond to someone else—but his first impulse afterward is to call Grace.

His longing is not just for romance but for the specific emotional safety he feels with her, someone who understands why the kiss feels both hopeful and disloyal. Grace’s near-moment with Henry on the couch during Edward Scissorhands is equally telling.

Her body finally wakes up to desire, yet the appearance of Tim in the bathroom mirror exposes how double-layered that desire is: she wants a new man while still loving the old one, and both loves are sincere. The eventual Christmas Eve kiss, surrounded by both families and framed by falling snow, matters less as a fairy-tale image and more as a public acknowledgment that moving forward does not mean loving less.

It is a moment where they accept that their future together will always contain ghosts and choose each other anyway.

Family, Friendship, and the Safety Net of Community

Throughout Grace and Henrys Holiday Movie Marathon, the private experience of grief is constantly bumped, annoyed, and soothed by family and friends who refuse to let the widowed characters disappear into isolation. Grace’s family is loud, meddling, sometimes tactless, and often exactly what she needs.

At Thanksgiving they fuss over the empty chair beside her, speculate about her romantic future, and embarrass her with references to Henry. Their behavior is not sensitive in a textbook way, but it keeps her rooted in a world where people still expect things of her: conversation, jokes, participation in traditions.

Her sister Ruth, with her blunt suggestion that Grace should at least have casual sex, provides a kind of comic relief that also carries real affection. Behind the crudeness is the instinct to remind Grace that her body and desires still exist and matter.

Henry’s family offers a similar mix of teasing and concern. His brother Cal uses Mario Kart, movie quotes, and banter about turkey to open a space where Henry can admit that he is not okay.

His parents invite him home every weekend, gently nudging him toward re-entry into normal life without demanding a timeline. Around them orbit other unofficial relatives: Maryellen with her orchestrated “Wi-Fi fix,” Miss Nadine watching the neighborhood, Win and Regina checking in about his planned move.

Grace’s world is further buttressed by the micro-community at Edgar Allan’s and the Italian Embassy—Dom with his comfort-food tastings and half-buried feelings for her, Zoe who treats the kids like regulars, bar patrons who willingly turn every screen to Elf and quote lines together. These people are not replacements for Tim or Brynn; they are the warm, exasperating crowd that keeps the widowed from drifting away.

The culminating Christmas Eve scene crystallizes this theme. Grace does not go to Henry’s parents’ house alone for a private, cinematic confession.

She arrives trailed by her children, her parents, extended family, and even the story of the rescued mice that Henry has been sheltering. Henry’s own family spills onto the porch.

Their kiss is witnessed, cheered, and folded into a shared holiday gathering. Community here acts as witness and blessing, saying in effect: we saw you at your worst, we watched you crawl through these months, and now we will stand around you while you risk happiness again.

Love happens between two people, but the courage to attempt it is sustained by everyone who keeps calling, checking, feeding, and gently scheming on their behalf.

Parenting, Childhood, and the Strange Honesty of Protecting Kids

The novel places Grace’s role as a mother at the center of her grief, using her choices with Ian and Bella to explore what it means to protect children without lying to them about how harsh life can be. On the day of Tim’s funeral, she takes her kids—still in black clothes—to adopt a dog.

Her own mother finds this unseemly, preferring a more decorous timetable, but Grace is following Tim’s posthumous “action plan” and her own intuition that the children need joy in their hands immediately, not at some respectable distance in the future. Buying food at Petco, joking about allergies, and walking into the SPCA in funeral clothes collapses the supposed boundary between mourning and ordinary errands.

Parenting in grief, the book suggests, is less about crafting perfect lessons and more about improvising a sequence of “next right things” that might give the kids something to love.

Grace’s little lies—claiming they are definitely not allergic to dogs, explaining that heaven has no cell towers—are not framed as moral failures but as acts of care that sit alongside her larger commitment to honesty. The children are already acquainted with death; Bella’s comment that the family cannot bring themselves to kill the mice because “they know what death means” is startling and true.

Ian’s art, Bella’s jokes, their willingness to watch sad movies and cohabitate with rodents show a kind of flexible resilience. They adapt to the idea that terrible things can happen and still insist on kindness toward small, vulnerable creatures.

At the same time, they push their mother toward life: Bella candidly observes that Dom is in love with Grace; both kids adore Henry, seek his attention, and later argue that he has made them “less sad.” When Ian wins the school art contest and texts Henry the photo, the adult’s breakdown in a record shop underlines how powerful it is for a grieving man to be invited into children’s milestones. Parenting here is shown as a two-way street: Grace is guiding Ian and Bella through loss, but their openness to new attachments and their pragmatic sense of death keep pulling the adults away from self-absorption and toward a future that includes pets, art contests, and new people at the table.

Guilt, Responsibility, and the Long Work of Forgiveness

A powerful current running through Grace and Henrys Holiday Movie Marathon is the question of who is to blame when tragedy strikes and whether forgiveness—of others and of oneself—is even possible. Henry’s internal narrative is dominated by the belief that his sulking on the morning of Brynn’s flight set off a chain of events that ended with the crash.

He cannot stop replaying his petty resentment about her work trip, his fear of moving to Los Angeles, and the sarcastic comment about sending a picture of LeBron James. In his mind, this ordinary marital spat becomes the crucial hinge of fate.

The randomness of a plane accident is easier to bear than the idea that indifference rules the universe, so he clings to the painful fantasy that he had enough power to save her and failed to use it. That belief is devastating but, perversely, comforting: it offers the illusion of control in a situation where he actually had none.

Grace’s confrontation with Tim’s emotional affair with Lauren Maxwell explores another form of guilt and betrayal. Reading thousands of emails, she discovers that Tim shared parts of himself with Lauren that he did not share with her: confidences, jokes, emotional confessions.

The hurt does not come from physical infidelity, which never happened, but from realizing that her supposedly exclusive emotional partnership was, in some ways, shared. Yet when she finally meets Lauren, the conversation complicates any simple villain narrative.

Lauren confesses she loved Tim, admits to a single kiss that he stopped, and insists that he chose Grace and the family. Grace leaves with a bitter-sweet sense of having been both wronged and protected.

Tim loved two women within the same life and still chose to stay where he was.

The near-mystical encounter where Brynn appears after Henry electrocutes himself provides a counterweight to his guilt. Brynn explicitly claims her own agency: she chose to be on that flight, and her last thoughts were of loving him, not blaming him.

That revelation does not erase the argument but reframes it as a tiny fraction of a much bigger story. Forgiveness in the novel is not a single turning point but a series of gradual releases.

Grace restrains herself from sending a spiteful email and instead opts for a brief, controlled message; Henry begins to accept that his power over Brynn’s fate was always limited. Both learn that love includes moments of pettiness, secrecy, and misjudgment, and that clinging to absolute purity only deepens suffering.

The book suggests that real forgiveness is less about declaring everything “okay” and more about deciding not to let past failures keep dictating every future choice.

Pop Culture, Holiday Movies, and Shared Rituals as Emotional Technology

Holiday movies, TV, and other shared rituals function in the story almost like emotional tools the characters use to handle feelings that are too big to face directly. Grace and Henry bond early over The Family Stone and Love Actually, not because these films are flawless but precisely because they are flawed and familiar.

Grace gleefully calls them problematic and “hate-watches” them, using sarcasm as a shield. Henry carries an inherited ritual of quoting Planes, Trains and Automobiles with his brother every Thanksgiving, a tradition that gives shape to a day otherwise overshadowed by the absence of Brynn.

Pop culture here is more than background; it is a language that allows people who are hurting to express affection, criticism, and nostalgia without having to speak in raw, therapeutic terms.

The structure of their developing connection is built around shared viewing. They first coordinate a simultaneous watch from different homes, then sit in the same room with Ian and the dog, and later watch Edward Scissorhands alone together.

Each shift marks a deeper level of intimacy. When Henry finishes The Family Stone while Grace sleeps, crying at the sentimental ending as he once did with Brynn, the film becomes a bridge between past and present loves.

Edward Scissorhands, with its strange mix of whimsy and sadness, mirrors Grace’s own conflict as she sits next to Henry, suddenly aware of her attraction. The scene where Winona Ryder’s character leans into Edward’s dangerous embrace becomes a mirror for Grace’s desire to lean into risk herself.

In the bar, Elf turns from background entertainment into a communal event. Screens that usually show sports pivot to a goofy Christmas movie, and patrons collectively quote lines.

It is a picture of how shared media can create instant community, even among strangers with different personal histories. By the time the characters end up planning to watch Love Actually together at Henry’s parents’ house on Christmas Eve, the film is less important than the pattern it represents: gathering, watching, feeling, and talking in the wake of storylines that give them permission to laugh and cry.

The novel treats movies and TV not as escapism that denies reality, but as containers that hold grief, love, and hope in digestible shapes, letting people rehearse their own emotions alongside fictional ones.

Art, Creativity, and Learning to See the World Again

Visual art and creativity emerge as another crucial channel for healing in Grace and Henrys Holiday Movie Marathon. Henry’s background in advertising and his private painting practice give him a way to understand both his own mind and Ian’s emerging talent.

When he takes the children to the Walters Art Museum, the visit is not just a field trip but a lesson in how different kinds of images open different doors in the viewer. The “old-timey” galleries bore Bella and feel distant, like a history that belongs to other people.

The contemporary exhibit, “The New Radicals,” however, energizes all three of them. Bold colors, strange compositions, and new techniques spark Ian’s imagination and prompt Henry to talk about artistic journeys, setbacks, and the long process of finding a voice.

In that setting, Henry shifts from grieving widower to mentor, giving the boy a language to describe what he already loves doing.

This bond continues through texts and video calls where they share drawings and ideas. When Ian works on his Elf-inspired drawing at the bar, using the movie as fuel, Henry’s encouragement is not casual.

He tells Ian stories about Beauford Delaney and James Baldwin finding beauty in a puddle, nudging him to look for inspiration in ordinary scenes, like Grace laughing with Dom outside the window. Art becomes a way to reinterpret the world—not just what is on the wall, but what is happening right in front of them.

When Ian later wins the school art contest, the moment confirms that Henry’s influence has mattered. The photo of Ian with his ribbon does more than make Henry proud; it reaches into his numbness and reminds him that he has already started a new narrative in which he is not just a man who lost his wife, but a man who helps a child see and be seen.

Grace, too, is shaped by this renewed way of seeing. She has always surrounded herself with the liveliness of a bar, with jerseys and sports décor, but Henry and Ian’s artistic focus causes her to see her own environment differently: the warm chaos of Edgar Allan’s, the snow-covered streets on Christmas Eve, the release of the mice in spring.

By the time she and Henry stand by the creek watching those mice disappear into the grass, they are participating in a kind of living artwork: a small, real-life performance about setting things free and watching what happens. Creativity here is not limited to drawings or paintings; it is the broader capacity to arrange experiences, memories, and hopes into shapes that make life bearable and sometimes even beautiful again.

Betrayal, Imperfect Love, and Emotional Complexity

The novel refuses to sanctify the dead as flawless saints. Instead, it insists on their humanity and the messy knots of love they left behind.

Tim’s emotional affair with Lauren Maxwell is a central example. Grace’s discovery of their correspondence is like being handed a secret archive of a different marriage running parallel to her own.

The volume of messages—thousands of emails—reveals a sustained intimacy, a relationship where Tim vented, joked, and confided in a way that suggests real attachment. For Grace, this does not simply rewrite her history with him as a lie; it fractures it into multiple truths.

She was loved, desired, and prioritized in many ways, and yet there was also a woman out there who shared his work frustrations and emotional life in a way Grace never fully knew.

Meeting Lauren in person complicates any easy verdict. Lauren is not a seductive caricature but a grieving woman in her own right, someone who genuinely loved Tim and lost him too.

Her confession that she kissed Tim once and that he stopped it, choosing his family, creates a bittersweet resolution that is neither total vindication nor total condemnation. Tim emerges as a flawed man who tried to honor his commitments while also feeding a part of himself his marriage did not fully meet.

Grace must absorb the fact that love can be real and deep even when it is not entirely exclusive. Parallel to this is Henry and Meredith’s nonrelationship.

Meredith is kind, appealing, and genuinely interested. Her small kiss is not a betrayal of Brynn, yet Henry’s heart is already tilting toward Grace.

Someone inevitably gets hurt or at least confused, not because anyone behaves monstrously, but because desire and timing rarely line up cleanly for everyone involved.

By allowing all these feelings to coexist—loyalty and resentment, gratitude and disappointment, desire and hesitation—the book insists that adult love is rarely pure. Grace’s imagined conversations with Tim even after she learns of Lauren, and Henry’s continued reverence for Brynn even as he falls for Grace, show that anger does not erase devotion and that new affection does not automatically heal old wounds.

The emotional reality is layered and sometimes contradictory, and the story allows that complication rather than forcing neat moral categories.

Fate, Choice, and the Limits of Control

From Tim’s meticulous “When I’m Gone” binders to Henry’s fixation on the argument before Brynn’s flight, Grace and Henrys Holiday Movie Marathon constantly pits human plans against forces that cannot be managed. Tim’s action plans are almost comically detailed: he chooses a coffin to match his office desk, selects a cemetery he jokes about, and scripts next steps for Grace and the kids, including the adoption of a mutt.

These preparations are tender and controlling at once. He is trying to soften the blow of his death by organizing it, as if grief could be project-managed with agendas and checkmarks.

Yet his plans cannot prevent the emotional shock of his illness, cannot keep Grace from being blindsided by his emotional infidelity, and certainly cannot anticipate that he will die in the same plane crash that kills Brynn. The randomness of that accident breaks any illusion that death follows a schedule.

Henry’s belief that his mood on a single morning determined Brynn’s fate is another attempt to wrest meaning from chaos. If he caused the problem, then the world is at least coherent; punishment fits crime, even if the crime was trivial and the punishment grotesquely disproportionate.

Brynn’s later appearance undercuts that belief, asserting her own choices and the larger randomness of the crash. The story does not present fate as a benevolent force but as a mixture of chance and individual decisions whose outcomes cannot be fully predicted.

Against that backdrop, smaller choices take on quiet importance: Grace deciding to adopt a dog that very day; Henry deciding to bring over an old Nintendo; Grace sending a measured email to Lauren instead of a furious one; Henry ultimately choosing not to move to Los Angeles despite career pressure.

The mice offer a more playful symbol of this theme. The kids decide not to kill them, the adults reluctantly accommodate that mercy, and Henry later takes on the role of their winter caretaker.

In the spring, he and Grace release them by a creek, acknowledging that once the mice run into the grass, anything can happen. Predators, weather, luck—all lies beyond their influence.

What they can control is the decision not to be executioners, to offer freedom rather than a guaranteed but limited safety. In the same way, Grace and Henry cannot control what new loss might come if they commit to each other, but they can decide to step into that uncertainty together.

The story encourages acceptance of limited control: plans matter, choices matter, but they exist inside a larger unpredictability that no amount of guilt or preparation can master.

Hope, Uncertainty, and Choosing to Live Forward

Hope in this story is modest, tender, and deliberately paired with uncertainty. There is no promise that Grace and Henry’s relationship will last forever, that they will never face another tragedy, or that their grief will vanish.

What the novel does offer is a series of scenes in which they decide, again and again, to move toward life rather than away from it. The Christmas Eve walk through the snow is not a flawless romantic gesture.

Grace is accompanied by a chaotic crowd of relatives, fueled partly by her children’s insistence and partly by the fresh knowledge that Henry has quietly been caring for the rescued mice. When she tells him she came there to kiss him, she is not announcing a completed transformation but marking the fact that she is willing to risk her heart while still carrying Tim’s memory and the sting of his secrets.

Henry’s response—kissing her first, welcoming her family into his parents’ home, and sitting down to watch Love Actually with a house full of people—signals his own decision to build something where emptiness once was.

The springtime epilogue by the creek distills the novel’s philosophy. Henry and Grace have become a couple; he has stayed in Baltimore instead of moving to Los Angeles; their shared life now includes kids, a dog, a bar, an art-loving boy, and a history of late-night movie calls.

Yet the release of the mice reminds them that control is always partial. Watching the animals disappear, they accept that the future is neither guaranteed nor safe.

The point is not to secure an outcome but to stand together while facing whatever arrives. Hope, then, is not a vague optimism that everything will “work out” but a chosen stance: to keep adopting dogs, teaching art, hosting parties, answering texts, and falling asleep during movies with people you love, even when the universe has already shown how suddenly it can take those people away.

In that sense, the entire “holiday movie marathon” of their winter is a long rehearsal for living forward—stringing together small acts of kindness, humor, and courage until, almost without noticing, they find themselves in a new season where grief and joy coexist and neither cancels the other.