Heart Lamp Summary and Analysis

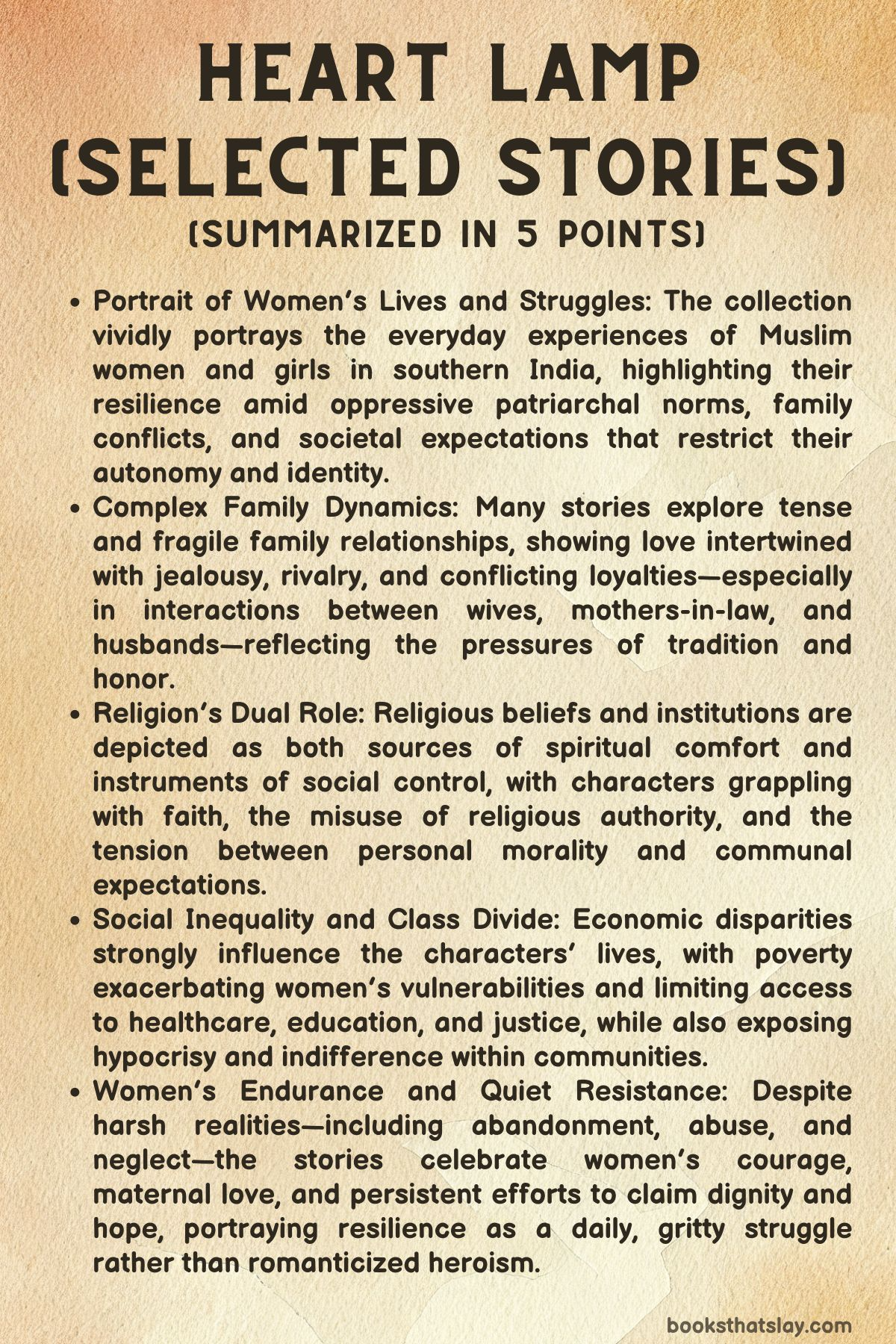

Heart Lamp: Selected Stories by Banu Mushtaq, translated by Deepa Bhasthi, is a collection of twelve stories portraying the everyday lives of women and girls in Muslim communities in southern India.

Originally written in Kannada, the stories blend dry humor with vivid, colloquial language to explore family tensions, social oppression, and women’s resilience. Mushtaq’s background as a journalist and lawyer shines through, revealing nuanced characters—from audacious grandmothers to hapless husbands—who navigate complex emotional landscapes. Winner of the 2025 International Booker Prize, this acclaimed work confronts caste and religious discrimination with wit and powerful insight.

The Stories

Stone Slabs for Shaista Mahal

The story is narrated by Zeenat, a woman who longs to escape the oppressive, chaotic city life full of noise, pollution, and indifferent people. When her husband Mujahid is transferred to work at the Krishnaraja Sagara dam project, she is relieved and hopeful for a quieter life surrounded by nature. Mujahid is a hardworking man, often absent, and their relationship is marked by mutual teasing but also traditional expectations and roles, which Zeenat critically examines.

At the new place, they meet their neighbors, Iftikhar Ahmed and his wife Shaista, who have six children. Shaista is a strong, warm-hearted woman struggling with the demands of motherhood and household duties, particularly concerned about her eldest daughter Asifa’s future and education. Iftikhar is devoted to Shaista, showing love and care in a way that impresses Zeenat and Mujahid, though Mujahid cynically compares it to a “dead love” like that symbolized by the Taj Mahal.

The story portrays the close bond forming between Zeenat and Shaista. Zeenat visits Shaista often, helps with the children, and supports her decision to pursue an operation to prevent more pregnancies after giving birth to a baby boy. Mujahid and Zeenat witness the tender moments in Shaista’s family life, contrasting with their own strained relationship.

Tragedy strikes when Shaista falls seriously ill and passes away shortly after childbirth. Zeenat and Mujahid rush to support the grieving family. After Shaista’s death, Iftikhar quickly remarries a younger woman to care for the children, which shocks Zeenat. The story ends on a somber note, with Zeenat reflecting on the harsh realities of love, loss, and societal expectations faced by women like Shaista, who despite their strength, remain vulnerable.

The narrative explores themes of marriage, love, duty, gender roles, motherhood, and the struggle between personal desires and societal pressures in the lives of women. It also highlights the contrast between romantic ideals and real-life complexities, particularly in the context of rural-urban shifts and traditional Muslim family dynamics.

Fire Rain

The story begins at dawn with mutawalli Usman Saheb waking up to find his wife Arifa exhausted from caring for their sick three-year-old son, Ansar. While concerned for his family, Usman is also consumed by anger over a family dispute: his youngest sister Jameela has demanded her rightful share of their late father’s property, which Usman manages. Despite her reasonable claim and his wife Arifa’s gentle counsel to honor her sister’s rights, Usman reacts harshly, torn between duty, pride, and frustration.

As the morning progresses, Usman tries to distract himself with mosque duties and a visit to a local hotel but is troubled by the sight and cries of crows, symbolic of his inner turmoil. Meanwhile, Arifa cares tirelessly for Ansar, reflecting her strength and compassion despite the household tensions.

The story expands into a broader community conflict when Sakeena, Usman’s widowed sister-in-law, and other needy locals approach him for help—financial aid, jobs, and social support—highlighting the many burdens on Usman as a community leader and family head. Amid this, a shocking event emerges: the body of Nisar, a troubled man who had cheated many including the mosque committee, was buried in a Hindu cemetery rather than a Muslim graveyard. This sacrilege ignites outrage in the Muslim community.

Usman seizes the moment to rally the community to exhume Nisar’s body and give him a proper burial, both as a religious duty and a political opportunity to regain support and influence. Despite his personal conflicts and moral doubts, Usman leads the effort, dealing with bureaucracy, local politics, and opposition.

In the story’s climax, during the funeral procession, a drunken man disrupts the solemnity, shaking Usman and the crowd. The body is finally buried properly, but Usman remains haunted by the uncertainty of whose body it really was and by the many unresolved struggles around him—family, faith, community, and his failing son’s illness.

The story closes on a note of tragic tension: Ansar is critically ill with meningitis, and the repeated echoes of family disputes and social responsibilities press heavily on Usman’s mind, symbolizing the burden of leadership and the fragility of life amid conflict and duty.

Black Cobras

The story revolves around Aashraf, a destitute woman fighting for justice for her sick child, Munni, amid societal neglect and patriarchal oppression. Despite her husband Yakub’s abandonment—driven by his desire for a son and a new wife—Aashraf persistently seeks help from the local mosque’s mutawalli (caretaker), Abdul Khader Saheb, who is indifferent and self-serving.

Aashraf’s plight highlights the harsh realities faced by women in her community: the stigma against having daughters, neglect by husbands, and the lack of institutional support. While Aashraf struggles to get financial aid for Munni’s medical treatment, her husband marries again, ignoring his responsibilities.

The mutawalli, though a religious authority, is corrupt and dismissive, quoting Sharia laws selectively to justify men’s actions and refusing to help Aashraf. The community silently witnesses Aashraf’s suffering. Despite the cold, rain, and social apathy, Aashraf sits outside the mosque, demanding justice.

Tragically, Munni dies from illness exacerbated by neglect. Aashraf’s confrontation with Yakub in the mosque ends violently, and Munni’s death symbolizes the failure of the community and religious authorities to protect vulnerable women and children.

The story closes with the community’s disdainful reaction toward the mutawalli and the realization of systemic injustice. Amina, the mutawalli’s wife, decides to take control of her life, choosing to get an operation to avoid more children, reflecting a desire to break free from oppression.

This narrative exposes gender bias, the misuse of religious authority, and the silent suffering of women in conservative settings, emphasizing the urgent need for justice and empathy.

A Decision of the Heart

Yusuf lives in a house divided between his wife Akhila and his widowed mother Mehaboob Bi, who raised him single-handedly with great love and sacrifice. Yusuf runs a successful fruit business but is caught in a tense domestic struggle. Akhila resents Yusuf’s devotion to his mother, especially his habit of eating dinner at Mehaboob Bi’s house and neglecting Akhila’s cooking. This ongoing conflict worsens until it escalates into physical fights and humiliation, including an incident where Akhila’s brother beats Yusuf.

To ease tensions, the family physically divides the house so Mehaboob Bi can live separately but nearby. Yusuf tries to treat both women equally, but Akhila’s jealousy and anger grow. The children take advantage of the discord. Akhila openly insults Mehaboob Bi, calling her a homewrecker, which deeply hurts Yusuf, who remains loyal to his mother.

The strife pushes Yusuf to a drastic decision: to arrange a remarriage for his mother, not just for her happiness but also as a way to calm the household tensions. This decision shocks the community and both Akhila and Mehaboob Bi. Yusuf searches for a suitable groom, rejecting unsuitable candidates. Meanwhile, Akhila vacillates between anger and remorse, even publicly confessing her mistakes to neighbors and begging for peace.

The wedding preparations become a focal point of the family’s struggle. Despite the bitterness and pain, Mehaboob Bi accepts the remarriage with dignity, seeking peace above all. Yusuf, exhausted by the turmoil and caught between his mother and wife, hopes this decision will bring harmony. The story closes with the family on the verge of this new beginning, filled with a mixture of hope, bitterness, and unresolved emotions.

Red Lungi

The story revolves around Razia, a woman overwhelmed by the chaos of summer vacation filled with noisy children—her own and many relatives’—who crowd her house, causing her severe headaches. To manage the noise and activity, Razia decides to have six boys from the family undergo khatna (circumcision), hoping this will enforce some quiet and rest. She arranges a large community event for the procedure, also including children from poorer families.

The event takes place in a local madrasa, with traditional and somewhat harsh methods of circumcision performed by a man named Ibrahim. The children scream and suffer through the painful ritual, but it is seen as a necessary and religious rite of passage. Among those circumcised is Arif, the cook’s son, who heals remarkably fast despite not receiving modern medical care, unlike Razia’s son Samad, who struggles with infection and pain after his hospital circumcision.

The story contrasts the rich and poor experiences, highlighting Arif’s resilience despite his poverty and threadbare clothes. Razia, witnessing Arif’s hardships and pure spirit, gifts him some of her son’s unused clothes. Meanwhile, Samad’s condition worsens, and Razia’s concern grows.

Ultimately, the story touches on themes of social disparity, the burdens of motherhood, religious tradition, and compassion across class divides. Razia’s final reflection — that while the rich have many helpers, the poor must rely on God — captures the poignant reality beneath the festive surface of the khatna ceremony.

Heart Lamp

Mehrun returns unexpectedly to her family home, carrying her baby and burdened by the pain of her troubled marriage. Her arrival shocks the household—her father, brothers, and mother react with silence, disbelief, and coldness rather than warmth. Mehrun reveals that her husband, Inayat, has abandoned her for another woman, a nurse he met during his hospital stay. Despite Mehrun’s pleas and heartbreak, her family appears powerless or unwilling to help, emphasizing the need to protect the family’s honor over her suffering.

Her brothers advise her to bear the situation, while her mother encourages patience and love. Feeling rejected and isolated, Mehrun refuses to return to her husband’s house, expressing her despair and the heavy toll of raising five children alone. Her family arranges to leave for Chikmagalur, but Mehrun resists, vowing not to be a burden.

Back at her husband’s home, Mehrun’s eldest daughter Salma hopes her uncles will confront Inayat, but the men instead engage in casual conversation, ignoring Mehrun’s pain. Inayat dismisses Mehrun coldly, treating her as a burden while openly flaunting his affair. Mehrun’s spirit is crushed by his harsh words and neglect, and she contemplates ending her life with kerosene and a matchbox.

At the darkest moment, Salma awakens to her baby sister’s cries and finds her mother attempting to set herself on fire. Her desperate pleas and embrace break through Mehrun’s despair. Holding her children close, Mehrun chooses to live, recognizing the strength she musters to be a mother for her children despite the loneliness and pain she endures. The story closes with a fragile hope emerging from profound sorrow.

High-Heeled Shoe

The story revolves around Nayaz Khan, a simple man captivated and obsessed by the glamorous, foreign lifestyle brought home by his sister-in-law, Naseema, who returned from Saudi Arabia with luxuries, especially a dazzling pair of high-heeled shoes. Nayaz fixates on these shoes as a symbol of wealth and status, longing for his wife Arifa to wear them and experience that elegance.

However, the family dynamics are strained. Nayaz’s elder brother Mehaboob, who lives abroad and returns rarely, is emotionally distant, partly due to Naseema’s controlling and mocking behavior. Nayaz invests borrowed money into renovating the old family home to impress his brother, but instead, the relationships become more fractured.

Naseema’s arrogance and materialism contrast sharply with Arifa’s weariness and frailty, especially during her pregnancy. When Nayaz finally buys the coveted high-heeled shoes for Arifa, they turn out to be ill-fitting and torturous for her. As Arifa struggles to walk in the shoes, she realizes they not only cause her physical pain but also threaten the life of her unborn child.

In a moment of dark clarity, Arifa understands the metaphorical weight of these shoes—symbols of greed, materialism, and societal pressure—that squeeze and suffocate her and the new life within. Summoning her inner strength, she fights to free herself and her baby from this oppression. In a powerful climax, the shoes break apart, and Arifa stands firmly, symbolizing liberation from superficial desires and reclaiming her own strength and identity.

The story is an exploration of material obsession, family conflict, societal expectations, and the resilience of a woman caught between tradition and change.

Soft Whispers

The story opens with the narrator abruptly awakened by a late-night phone call from her mother (Ammi), who informs her that Abid, the son of Mujawar Saheb and now the caretaker of a local shrine, has come from their ancestral village Malenahalli. The village is closely tied to their family, and an important Urs festival is approaching, during which a family member must attend the sandalwood ritual. Though reluctant, the narrator agrees to meet Abid later.

The narrative then drifts into a vivid memory of the narrator’s childhood in Malenahalli, especially of her affectionate relationship with her grandmother (Ajji) and grandfather (Ajja). Ajji, a strong and spiritual woman, takes care of the children, shares tobacco, and prepares for the narrator’s upcoming birthday, showing deep familial love and tradition. Despite hardships—like the narrator’s mother’s worry about new clothes and her father’s distant government job—the warmth and community life in the village are lovingly portrayed.

Ajji’s spiritual wisdom shines in her exchanges with Jaffar Baba, a local tailor with philosophical debates about life, freedom, and purity of heart. Ajji insists that spiritual enlightenment isn’t exclusive, highlighting the importance of purity and love.

On the narrator’s birthday, the tailor’s poorly stitched frock brings amusement but also joy, and the children’s playtime leads to a cruel but captivating sparrow-catching game organized by Abid. The narrator falls and gets injured, and though embarrassed and hurt, she finds comfort in Ajji’s care. The narrative turns darker when Abid kisses the narrator unexpectedly, causing her confusion and distress, but Ajji’s unwavering support helps her feel safe again.

Later, the narrator recalls an incident involving a pregnant woman’s craving for Ajji’s fish curry, leading to a miraculous birth, blending rural superstition with love and care.

The story closes in the present, with the grown-up narrator meeting Abid again. He has become the respected supervisor of the family’s shrine and appears formal, shy, and respectful, contrasting with his mischievous boyhood self. The narrator senses the complexity in people—their ability to change yet retain hidden traits—and ponders how people can “turn everything upside down.”

This tale weaves together themes of childhood innocence, family bonds, tradition, spiritual wisdom, and the bittersweet passage from youthful mischief to adult responsibility.

A Taste of Heaven

Shameem Banu’s family struggles to understand her sudden change in behavior, which her husband Saadat attributes to menopause. Their home is tense, with Shameem’s temper often flaring, especially towards their children—showing favoritism to her eldest son Azeem and harshness to her daughters, particularly Aseema. Saadat endures this with patience, trying to maintain peace despite his own hurt and confusion.

The household is complex, with Shameem having entered a large extended family burdened with responsibilities. Her frustrations mount over years of caretaking, managing family demands, and the departure of a sister-in-law, leading to a harsh demeanor even toward family members like the youngest brother-in-law, Arif, whom she drives away. This incident saddens everyone, especially the children.

A key figure in the family is Bi Dadi, Saadat’s elderly aunt, who selflessly cares for the household but becomes the focal point of a tragic misunderstanding. When Azeem unwittingly uses her cherished, old prayer mat (ja-namaz) to clean his bike, it causes Bi Dadi deep emotional pain. Despite attempts to console her with a new prayer mat, she falls into despair, stops praying, and cries constantly. The family’s efforts to help only increase tension, and Shameem Banu eventually sends Bi Dadi to Arif’s house, but peace remains elusive.

After some days, Azeem brings Bi Dadi back home. Her condition worsens as she forgets prayers and complains directly to God. The children stage a playful “heavenly” drama by giving her a bottle of Pepsi, which Bi Dadi calls “aab-e-kausar” (the heavenly drink). This imaginative act brings her joy and peace, and she withdraws into a blissful, otherworldly state, feeling reunited with her deceased husband.

Bi Dadi’s health stabilizes in this state of “heaven,” sustained only by her “aab-e-kausar.” Though this worries Azeem, and strains family finances, it also brings a fragile calm to the household. Saadat continues to rationalize his wife’s difficult behavior as menopause, while Shameem grows less hostile towards Bi Dadi. The story closes with Bi Dadi living peacefully in her imagined heaven, free from worldly pain, while her family copes with the realities around her.

The Shroud

Shaziya, who often blamed her late waking for dawn prayers on high blood pressure and “Shaitan’s game,” wakes one day to distressing news: Yaseen Bua, a poor woman who had once visited Shaziya’s house uninvited and requested a shroud soaked in holy Zamzam water from Mecca, has died. Yaseen Bua’s last wish was to be buried in this special kafan, but Shaziya had forgotten to fulfill her promise while on Hajj.

During their pilgrimage, Shaziya became distracted by shopping and overlooked bringing the kafan for Bua. Upon returning home, she finds herself haunted by guilt and the urgency of fulfilling Bua’s wish. She frantically searches among relatives and friends for such a kafan but finds none. The pressure mounts as Bua’s son, Altaf, insists on using only the Zamzam-soaked kafan for her burial, or else the funeral cannot proceed.

Shaziya struggles with her own pride, anger, and helplessness as she confronts the consequences of neglecting a humble yet deeply important promise. Farman, her son, helps arrange the burial with a kafan bought locally but without the sacred Zamzam water, and comforts Shaziya through her sorrow.

At Yaseen Bua’s funeral, Shaziya’s grief is profound and visible to all. Outsiders might misunderstand her sorrow as grief over a servant, but for Shaziya, it is a painful reckoning with her own failings and the spiritual weight of an unkept promise — realizing that in a way, it is not Bua but Shaziya who is truly being laid to rest in sorrow.

The Arabic Teacher and Gobi Manchuri

The narrator, a working mother juggling a demanding legal career and raising two daughters, is tasked with ensuring her children receive proper religious education, particularly learning Arabic and Qur’anic recitation. Her younger brother, Imaad, helps by finding an Arabic teacher named Hazrat, a young, reserved man from Uttar Pradesh, who begins teaching the girls in the evenings.

Though initially anxious about the teacher’s interactions with her daughters, the narrator pays him well, appreciating the progress the girls make in their religious studies. However, an unexpected incident reveals the teacher’s odd obsession with gobi manchuri—a cauliflower dish. The girls and the cook try to make the dish for him, but the plan backfires when the narrator walks in, and the teacher flees, embarrassed.

Later, rumors spread about Hazrat’s unusual behavior, including his strange demands regarding gobi manchuri when marriage proposals are considered. Despite concerns, he eventually marries, and the narrator feels some relief. But that relief is short-lived when a young woman and her brother come to the narrator seeking help: the teacher, now the husband, is abusive, punishing his wife for not making the gobi dish to his liking. The community’s attempts to intervene have failed, and the woman is suffering.

The narrator, troubled by the situation and determined to help both the woman and possibly save the marriage, contacts her brother for advice while simultaneously searching for a gobi manchuri recipe—hoping to use the peculiar obsession as a means to resolve the crisis.

The story highlights the complexities of social roles, responsibility, and the unexpected consequences of seemingly small obsessions within a traditional family and community context.

Be a Woman Once, Oh Lord!

This story is a heartfelt plea from a woman’s perspective, narrating her life’s journey filled with pain, oppression, and shattered dreams. She begins by addressing God, recognizing His vast creation and the order of heaven and hell, but then humbly asks for His attention to her one small, urgent request.

The woman recalls her childhood innocence and sheltered life, confined within walls and obedience, taught to revere and serve men as divine figures, especially her husband. When she marries, she is uprooted from her loving mother’s care and thrust into a new home where she loses her identity and freedom, becoming simply “his wife.” Her husband’s cruelty, greed, and domination over her body and spirit grow relentlessly. She is silenced, controlled, and used, her emotions and desires suppressed.

Despite bearing children and enduring physical and emotional abuse, her husband’s arrogance and selfishness escalate, culminating in his demand for money from her family and his eventual decision to marry another woman. Society and even religious teachings appear complicit, advising her to accept her subjugation and seek legal remedies that will take years, while her own cries remain unheard by the divine.

After a painful surgery, she refuses to give up a cherished necklace symbolizing her mother’s love, an act of defiance that fuels her husband’s hatred. She finds herself abandoned, locked out of her own home, left to struggle alone with her children and heartbreak. The story ends with her witnessing her husband bringing home the new wife, wrapped in gold-embroidered cloth — a cruel echo of how she was once brought into his life.

In her final, powerful appeal, she asks God to understand what it truly means to be a woman, to feel the pain, the injustice, and the resilience required to live in her shoes. She urges Him to “be a woman once,” to grasp the harsh realities women endure and to create the world with true empathy and fairness.

The story is a searing critique of patriarchy, societal norms, and divine silence in the face of women’s suffering, voiced through the raw emotions of a woman’s lived experience.

Analysis of Themes

Gender and Patriarchy

Heart Lamp paints a vivid and unflinching picture of how deeply entrenched patriarchal norms shape the lives of women in Muslim communities of southern India.

Women are portrayed in roles where their worth is measured primarily through their relationships to men—as daughters, wives, and mothers—and their desires and individuality are often suppressed or ignored. This theme emerges strongly in stories like “Stone Slabs for Shaista Mahal” and “Black Cobras,” where women carry the emotional and physical burdens of motherhood and household duties under restrictive social expectations.

The tension between personal autonomy and societal roles manifests through characters like Shaista, who tries to control her reproductive destiny, or Aashraf, who faces neglect and injustice due to her gender and status.

Men’s authority is reinforced through legal, religious, and social structures, as seen with the mutawalli’s selective use of religious law to justify male privilege and dismissal of women’s suffering. Yet, the stories also reveal women’s quiet, persistent resistance and resilience in the face of these oppressive frameworks.

Their struggles are not only against individuals but against a system that normalizes control and subjugation, leaving women vulnerable but also revealing their strength and agency within constrained spaces.

This theme exposes the complex interplay of power, tradition, and gender, critiquing how deeply societal institutions sustain inequality while showing the human costs borne largely by women.

Family Dynamics and Conflict

The stories highlight the fragile and often tense nature of family relationships, illustrating how love, duty, loyalty, and resentment coexist in intimate domestic settings. Families are depicted as both sources of comfort and sites of profound conflict.

In “A Decision of the Heart,” the clash between a wife and mother-in-law creates a divided household where love and jealousy coexist, forcing drastic decisions such as the remarriage of a widowed mother to restore peace.

Similarly, “Heart Lamp” explores how Mehrun’s abandonment by her husband triggers indifference and silence from her own family, emphasizing how family honor often trumps individual suffering. These narratives show that family is not simply a sanctuary but a battleground for power and emotional survival. The interactions between spouses, parents, children, and siblings reveal generational tensions, cultural expectations, and competing loyalties.

The weight of family honor, social reputation, and tradition complicates the possibility of reconciliation and support, often leaving women caught between competing demands. This theme explores how personal emotions are entangled with social codes within the family structure, underscoring the complexity of human relationships shaped by cultural and gendered expectations.

Religion and Social Authority

Religious belief and institutions play a central role in shaping the moral and social order in the communities depicted in Heart Lamp: Selected Stories. However, this influence is portrayed with nuance, showing both spiritual depth and the potential for misuse of religious authority.

The mosque and its caretakers represent centers of community power, as seen in “Fire Rain” and “Black Cobras,” where the mutawalli’s decisions impact not only religious rituals but also social justice. Yet, religion is often manipulated to justify patriarchal control or political ambition, rather than genuine compassion or equity.

Characters like Usman use religious duties as a means to consolidate influence, while the mutawalli selectively interprets religious law to dismiss women’s grievances. At the same time, spiritual themes of purity, tradition, and community are lovingly rendered, as in “Soft Whispers,” where faith and family intertwine with childhood memories and village life.

The stories also expose the tension between religious obligation and personal morality, showing characters wrestling with faith in the face of injustice and suffering. This theme captures the complex relationship between religion as a source of identity and guidance, and its institutionalized forms that can reinforce social hierarchies and inequalities.

Social Inequality and Class Divide

Economic disparity and social stratification are crucial undercurrents in the narratives, exposing how poverty and privilege affect the characters’ lives in profound ways.

In “Red Lungi,” the contrast between the wealthy and the poor is vividly illustrated through the khatna ceremony, where children from different social classes endure the same ritual but experience vastly different outcomes due to unequal access to medical care and support.

The story highlights the resilience of the poor, like Arif, who endures hardship with dignity, juxtaposed with the protective buffer surrounding the wealthy. This disparity is further seen in “Black Cobras,” where Aashraf’s desperate pleas for help reveal the apathy of religious and community institutions toward the marginalized. The economic struggles of families influence decisions about marriage, education, healthcare, and survival, showing how class intersects with gender to compound vulnerability.

Social inequality is not only material but deeply social, reflected in the stigma, exclusion, and neglect that the less privileged face within their own communities. These stories critique the uneven distribution of resources and compassion, illustrating how systemic poverty limits opportunity and perpetuates suffering while highlighting moments of compassion that cross class boundaries.

Resilience and Survival of Women

Throughout Heart Lamp, women emerge as figures of remarkable endurance, navigating immense challenges imposed by societal structures, family pressures, and personal betrayals.

Despite facing abandonment, abuse, poverty, and social exclusion, many female characters find ways to assert their dignity and fight for their children’s well-being. Mehrun’s decision in “Heart Lamp” to resist despair and live for her children after contemplating suicide captures a profound human strength rooted in maternal love. Similarly, Amina in “Black Cobras” chooses to control her reproductive future, signaling a desire for autonomy even in constrained circumstances. The stories acknowledge the harsh realities of women’s lives but also celebrate their courage and inner resources. Women’s resilience is not romanticized but shown as a gritty, ongoing struggle—marked by moments of quiet defiance, sacrifice, and hope.

This theme underscores the dual nature of women’s experience: shaped by oppression but also shaped by the will to endure, protect, and claim space within a world that often denies them. It affirms the persistence of human spirit amid adversity and critiques societal failure to support or protect women adequately.