Hell Bent by Leigh Bardugo Summary, Characters and Themes

Hell Bent by Leigh Bardugo is a dark fantasy thriller that continues the journey of Alex Stern, a Yale student who operates in the shadowy world of occult societies and ghostly undercurrents. As a sequel to Ninth House, the novel follows Alex as she battles supernatural forces, university politics, and her own haunted past in a desperate attempt to rescue her mentor, Darlington, from hell.

The novel blends contemporary academia with arcane horror, bringing readers into a world where the Ivy League’s most prestigious institutions mask terrifying secrets. At its heart, it explores trauma, loyalty, justice, and the cost of wielding power.

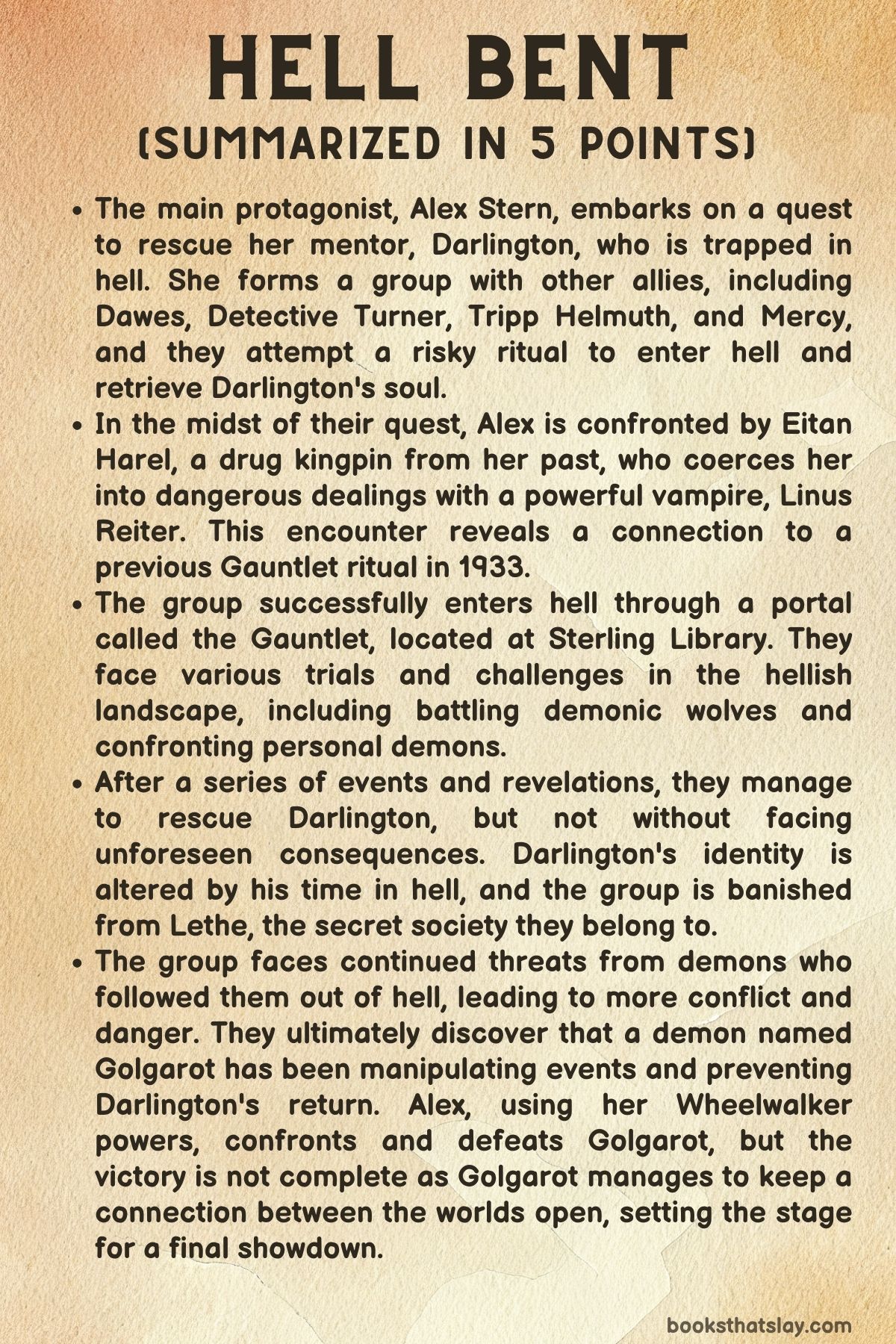

Summary

Alex Stern, a student at Yale and member of Lethe—the secret society tasked with overseeing magical practices on campus—embarks on a dangerous mission to rescue her mentor, Darlington, who is trapped in hell. The story begins in New Haven with Alex confronting Chris “Oddman” Owens, a low-level criminal, using a magical disguise and ghostly possession.

The encounter spirals out of control when the ghost, Derrik, takes over her body, revealing how unstable her connection to the spirit world has become. Shaken, Alex retreats, aware that she is walking an increasingly perilous line between the living and the dead.

Back on campus, she learns from her partner Dawes that a new Praetor has been appointed to supervise Lethe. This development threatens their secret operation to retrieve Darlington.

At a sanctioned ritual conducted by the Book and Snake society, they animate a corpse to glean intelligence. The dead man spells out “Galaxias,” which Dawes links to earlier clues from Darlington, reinforcing the urgency of their mission.

They begin planning an unsanctioned ritual to access hell through Scroll and Key’s tomb.

In a failed attempt to open a portal, Alex and Dawes unleash demonic horses that damage sacred artifacts and nearly kill them. Their disobedience is discovered by Lethe leadership, leading to warnings and threats.

Nonetheless, the two press on. At Black Elm, Darlington’s ancestral home, they discover him trapped within a magical circle, transformed with demonic features but still retaining fragments of his personality.

He asks for books and pleads for rescue, revealing that each day trapped chips away at his humanity.

Alex’s emotional bond with Darlington pulls her into a series of nightmarish events. She sleepwalks to Black Elm, where Darlington appears calm and intellectual, yet admits his imprisonment is slowly consuming him.

He urges Alex to find the Gauntlet—the portal to hell—and make the descent. Meanwhile, Alex resumes fieldwork with Turner, a detective tied to Yale’s magical misdeeds.

A professor’s mysterious death hints at deeper conspiracies, and Alex discovers that she may be something ancient and feared—a Wheelwalker, capable of moving between realms.

The team finally organizes a full-scale descent into hell. Alex, Dawes, Turner, and Tripp perform a ritual involving blood, fire, and memory beneath Sterling Library.

The portal opens to a boiling river, which judges each traveler. Alex is nearly consumed, plagued by guilt over her past violence.

Emerging into an infernal version of New Haven, they face demonic trials shaped by their histories. In parallel, Pamela, a timid Lethe staffer, musters courage to defend Il Bastone from an intruder, killing a demon to protect Alex.

As the group advances, each member confronts personal trauma: Tripp recalls allowing his cousin to drown, Turner reflects on killing his corrupt mentor to preserve justice, and Alex is possessed by Hellie, her murdered friend. Hellie gives Alex strength and closure, allowing her to face her tormentors and reclaim control.

They reach the ruins of Black Elm in hell, where Darlington toils under demonic compulsions. Alex invokes the memory of a kind old man who cared for Darlington, helping him break free.

His soul is captured in a magical container, but their exit is blocked by demonic wolves. Darlington, now partially demon, sacrifices himself so the group can escape.

They awaken back in the mortal world, altered and traumatized. Their hellish journey has changed them—physically and spiritually.

As they recover, they learn that hell’s influence still lingers. Demons watch from towers, and the portal may still be open due to the blood Anselm, Lethe’s superior, stole from Alex.

In a final act of resistance, Alex drags Eitan Harel—her abuser and tormentor—into hell, offering his soul as a replacement to seal the gate.

The group confronts more mysteries. Michelle Alameddine, once Lethe’s favorite, is found dead in Reiter’s car.

Darlington reveals she was his familiar, caught between service and betrayal. They give her a funeral, honoring her tragic choices.

Tripp, presumed lost, returns as a vampire but retains his goofy, human spirit. Against Darlington and Turner’s objections, Alex allows him to stay, insisting redemption is possible.

As they burn bodies and reflect on their trials, the book ends with the threat unresolved. A demon perched atop Harkness Tower signals that the barrier between worlds remains fragile.

With Darlington at her side, transformed yet loyal, Alex prepares to defend their reality. No longer just a reluctant survivor, she declares herself the storm, ready to wield her power and face whatever hell demands next.

Characters

Alex Stern

Alex Stern is the fierce, flawed, and fractured heart of Hell Bent. Marked by a traumatic past that includes drug addiction, ghostly visitations, and survivor’s guilt, she is a woman in constant battle with herself and the forces around her.

Alex’s ability to see and interact with ghosts defines her place in Lethe, but it also isolates her, forcing her to navigate the liminal space between the living and the dead. Her sarcasm and toughness mask a profound vulnerability, especially in moments when she reflects on her friendship with Hellie or her deepening bond with Darlington.

Her mission to rescue Darlington is not just a logistical challenge—it’s a spiritual quest for redemption, for making amends, and for reclaiming parts of herself she fears are lost. As the novel progresses, Alex evolves from a reluctant participant in Lethe’s secretive world into its boldest and most formidable agent.

Her transformation into a Wheelwalker—a being capable of moving between life and death—positions her as both a savior and a threat, someone who embodies the book’s central theme: the peril and power of crossing boundaries.

Darlington (Daniel Arlington V)

Darlington is both the literal and symbolic embodiment of nobility corrupted by circumstance. Once a gentleman scholar who upheld Lethe’s traditions and ideals, he is transformed into a part-demon entity after his descent into hell.

Despite his monstrous appearance and infernal afflictions, Darlington clings to civility and humanity with every ounce of strength. His mental discipline, moral code, and even his yearning for books reflect his resistance to becoming what hell demands of him.

The contrast between his glowing, horned form and the tender way he addresses Alex or mourns the loss of his family and home speaks volumes about his internal struggle. Through Darlington, the novel explores the question of identity when stripped of physical and social markers.

He becomes a mirror for Alex—another person suspended between worlds, trying to remember what it means to be human. His ultimate act of sacrifice to ensure his companions’ escape underlines the nobility he has fought to retain and deepens the emotional core of the narrative.

Pamela Dawes

Dawes is the intellectual anchor of the group, Lethe’s librarian and archivist whose arc charts the rise of quiet courage. Initially timid and terrified of stepping outside the rigid boundaries of academic safety, she blossoms into an indispensable partner in Alex’s rebellious mission.

Dawes’s deep knowledge of magical lore is rivaled only by her growing willingness to risk herself for others. Her vulnerability—seen in her fears of disapproval and failure—is met with Alex’s fierce loyalty, resulting in one of the most profound and trusting relationships in the book.

Dawes’ ability to read and interpret arcane signs, her sensitivity to ethical implications, and her meticulous planning all complement Alex’s instinctive bravery. As Dawes moves from fear to action, particularly in summoning rituals or fighting off demonic threats, she becomes a symbol of how intellect and empathy can be just as powerful as raw magical talent.

Turner

Detective Turner occupies a unique space as both a figure of authority and an outsider. A mortal law enforcer reluctantly entangled in Lethe’s affairs, Turner brings with him a hard-earned sense of justice and a moral compass sharpened by systemic betrayal.

His backstory—especially the moral crisis surrounding his mentor Carmichael’s corruption—reveals a man who chooses to bear burdens rather than ignore them. Turner is pragmatic, skeptical, and emotionally reserved, but underneath that lies a deep sense of honor.

His grudging partnership with Alex evolves into a wary mutual respect, marked by honesty and accountability. Turner’s humanity, especially in the face of magical absurdity and bureaucratic evasion, provides a necessary counterweight to the more fantastical elements of the narrative.

He represents the ethical dilemma of choosing the lesser evil and underscores the price of being the one who acts when others look away.

Tripp Helmuth

Tripp begins as comic relief—a privileged, somewhat bumbling member of Lethe whose usefulness seems marginal. Yet, his true depth is slowly and deliberately revealed.

Haunted by childhood trauma, particularly the memory of watching his cousin drown without intervening, Tripp embodies the theme of passive complicity. His presence in the journey to hell is quietly redemptive; he faces horrors and acts with unexpected bravery.

His eventual transformation into a vampire—without losing his kindness or humanity—underscores one of the book’s boldest arguments: that monstrosity and decency can coexist. Tripp challenges the assumption that power necessarily corrupts and becomes a symbol of second chances.

His continued awkwardness and humility, even after gaining supernatural powers, serve as a poignant reminder that identity is shaped more by choice than by circumstance.

Hellie

Hellie, Alex’s murdered best friend, appears posthumously yet powerfully, first in memory and later through possession. As a ghost, she symbolizes both trauma and resistance.

Her integration into Alex’s body during the descent into hell brings both emotional catharsis and supernatural strength. Hellie is the emotional foundation of Alex’s resolve, the one person who saw and accepted Alex for who she was.

Her reappearance serves not only to confront past wounds but to empower Alex in reclaiming her agency. When Hellie’s spirit aids Alex in attacking their abusers, it becomes an act of vengeance, closure, and love all at once.

Hellie’s legacy lingers as a protective and guiding force, shaping how Alex relates to power, memory, and justice.

Eitan Harel

Eitan Harel is the embodiment of worldly menace—an Israeli gangster who wields mortal power through threats, manipulation, and control. He operates outside Lethe’s magical rules but becomes entangled with its consequences when Alex uses him as a scapegoat to escape hell.

Eitan’s dominance over Alex in earlier scenes highlights her vulnerability and desperation, while his eventual downfall illustrates her evolution into someone capable of rewriting power dynamics. He is a character who thrives on exploitation, his demise satisfying in its poetic justice.

His arc brings the street-level criminal world into contact with ancient, infernal forces, blurring the lines between mundane evil and cosmic consequence.

Michael Anselm

Anselm functions as both a bureaucratic antagonist and a manifestation of the corrupt institutions Lethe pretends to stand above. As a board member and later a demonic adversary, he manipulates systems of power to protect his own interests, portraying authority without accountability.

He is the ultimate gatekeeper, using his influence to suppress dissent and maintain control. His transformation into a demonic being in hell is less a surprise than a revelation of his true self.

He attempts to lure Alex with illusions of comfort and belonging, revealing a sophisticated understanding of psychological warfare. His final defeat—engineered by Alex’s cunning and rage—marks a pivotal moment where institutional betrayal is met with insurgent justice.

Mercy and Lauren

Mercy and Lauren, Alex’s friends and housemates, provide moments of levity, normalcy, and emotional grounding. While not directly involved in Lethe’s magical missions, they reflect what is at stake: the preservation of innocence, connection, and life untouched by darkness.

Mercy, in particular, plays a more active role, dousing Eitan with Datura oil at a crucial moment, thereby saving Alex. Their loyalty and trust underscore the importance of found family and emotional bonds in a world rife with secrets and supernatural peril.

They represent what Alex fights to protect—even if she can never fully return to that simpler world.

Themes

The Fragility and Corruption of Power

Power in Hell Bent is not only elusive but often self-defeating. Alex Stern’s command over necromancy and ghost-channeling is riddled with volatility, such as when she loses control during her encounter with Oddman.

Her increasing reliance on supernatural entities like Derrik shows how her perceived strength is simultaneously her most dangerous vulnerability. Likewise, Lethe, the institutional guardian of magical order, appears powerful on paper but is revealed to be bureaucratically rigid, short-sighted, and threatened by any deviation from sanctioned rituals.

The fractured Round Table at Scroll and Key becomes emblematic of this flawed authority—the physical destruction mirroring a spiritual and organizational failure. Even Darlington’s transformation into a demonic figure illustrates how power, once mishandled or unbalanced, corrupts what was once noble.

Yet it is not only institutional or magical power that is corruptible—Eitan’s criminal leverage over Alex demonstrates how mundane power, too, is built on fear and exploitation. Ultimately, power in this narrative is always conditional, destabilized by guilt, trauma, bureaucracy, and betrayal.

Its exercise often isolates the wielder and distances them from their own humanity.

Guilt as a Form of Identity

Alex’s relationship with guilt transcends emotional burden; it becomes central to how she understands herself. Whether facing judgment in the boiling river or reliving personal losses like Hellie’s death or the killing of Babbit, Alex is constantly framed as someone who believes she deserves punishment.

Her self-perception as morally compromised contrasts with her role as a protector and redeemer. While other characters—Turner, Tripp, Dawes—grapple with isolated ethical choices, Alex’s guilt is pervasive and foundational, shaping her worldview and her willingness to sacrifice herself.

Even her magical designation as a Wheelwalker seems to be an outgrowth of her internalized responsibility to navigate realms others cannot. Her guilt drives action, deepens empathy, and ultimately allows her to empathize with the damned, particularly Darlington.

She is not simply haunted by her past; she interprets her very existence through its lens. This makes her choices emotionally loaded and constantly at risk of becoming self-sabotaging.

But this same guilt also sharpens her moral clarity and fuels her need to do what others cannot or will not, giving her a paradoxical strength.

Reclamation Through Transformation

Transformation is not merely thematic in Hell Bent—it is the engine of character development and resolution. Darlington’s evolution from gentleman scholar to horned demonic being is literal and symbolic, reflecting both what has been lost and what is still reclaimable.

Though altered, his core virtues—intellect, loyalty, and moral compass—remain accessible, especially through his interactions with Alex and his need for literature. Similarly, Tripp’s shift from forgettable sidekick to reluctant vampire illustrates a surprising continuity of identity even within radical physical change.

What defines these characters is not the trauma of transformation but their reaction to it—their will to retain agency, humanity, and memory. Even Alex, though never fully demonized, changes drastically: from a girl ruled by shame to someone who can command a metaphysical Wheel and wield hellfire.

These metamorphoses challenge the idea that identity is stable or should be preserved unchanged. Instead, the book champions adaptability and emotional truth as the real markers of the self.

Survival is never about resisting change but embracing it without forfeiting moral orientation.

The Limits and Necessity of Institutional Trust

Throughout Hell Bent, Lethe Society is positioned as a double-edged sword—essential for preserving magical order, yet obstructive and unyielding when true stakes are involved. Alex and Dawes must conceal their mission not from adversaries, but from the very institution tasked with overseeing it.

Their workarounds, lies, and illicit rituals are born not out of rebellion but necessity. Lethe’s failure to believe in Darlington’s survival—or to support efforts to rescue him—highlights the inadequacy of hierarchical authority in matters requiring courage, nuance, and urgency.

Michael Anselm embodies this problem, fixated more on control than outcomes, willing to threaten Alex’s expulsion rather than address the systemic dangers emerging from hell. This institutional rigidity stands in stark contrast to the flexible, collaborative ethics of Alex’s group, who find success precisely because they trust each other over Lethe’s decrees.

In the end, the story critiques the idea that official systems can ever be completely relied upon for moral or strategic leadership. The burden of righteous action falls on the individuals willing to risk their standing to do what is right.

The Sacredness of Memory and Grief

Memory in Hell Bent functions not as nostalgia but as ritual—a sacred act that holds together fractured identities and broken timelines. From Alex’s spectral encounters with Hellie and Babbit to Tripp’s reflections on his cousin’s drowning and Turner’s recollection of Carmichael’s betrayal, grief operates as a central driver of character motivation.

These aren’t incidental flashbacks but emotional echoes that shape every step of the descent into hell. In Darlington’s case, even his monstrous form clings to remnants of the past—books, conversations, rituals—suggesting that memory is the final refuge of the self when everything else erodes.

The characters do not try to forget their traumas; they channel them. Grief is not something to be resolved, but something to be understood and honored.

When Alex experiences a vision of paradise with all her lost loved ones, it becomes a test of her ability to recognize illusion and choose the hard truth. Ultimately, memory in this story isn’t just painful—it is redemptive, grounding the characters when the physical and moral world collapses around them.

Redemption as Resistance

Redemption in Hell Bent is not offered—it is fought for, demanded, and often seized in moments of impossible defiance. Whether it’s Turner covering up Carmichael’s murder to prevent greater harm, Tripp choosing to live as a vampire without harming others, or Alex trading Eitan’s soul for her own freedom, the characters all redefine what salvation looks like.

Traditional paths to forgiveness or absolution are blocked or corrupted. Instead, they carve new ones through grit, sacrifice, and moral imagination.

Importantly, redemption in this story is not about innocence regained but about culpability redirected into strength. Alex does not deny her past; she learns to use it.

Darlington does not undo his demonic evolution but channels it toward protection and loyalty. Even Mercy, often at the periphery, becomes a catalyst for action when she executes Alex’s trap.

In every case, redemption comes with risk, and the cost is never low. But by asserting the right to fight for their future, each character resists the inevitability of damnation and asserts a new kind of agency—one rooted in solidarity, not purity.