Hera by Jennifer Saint Summary, Characters and Themes

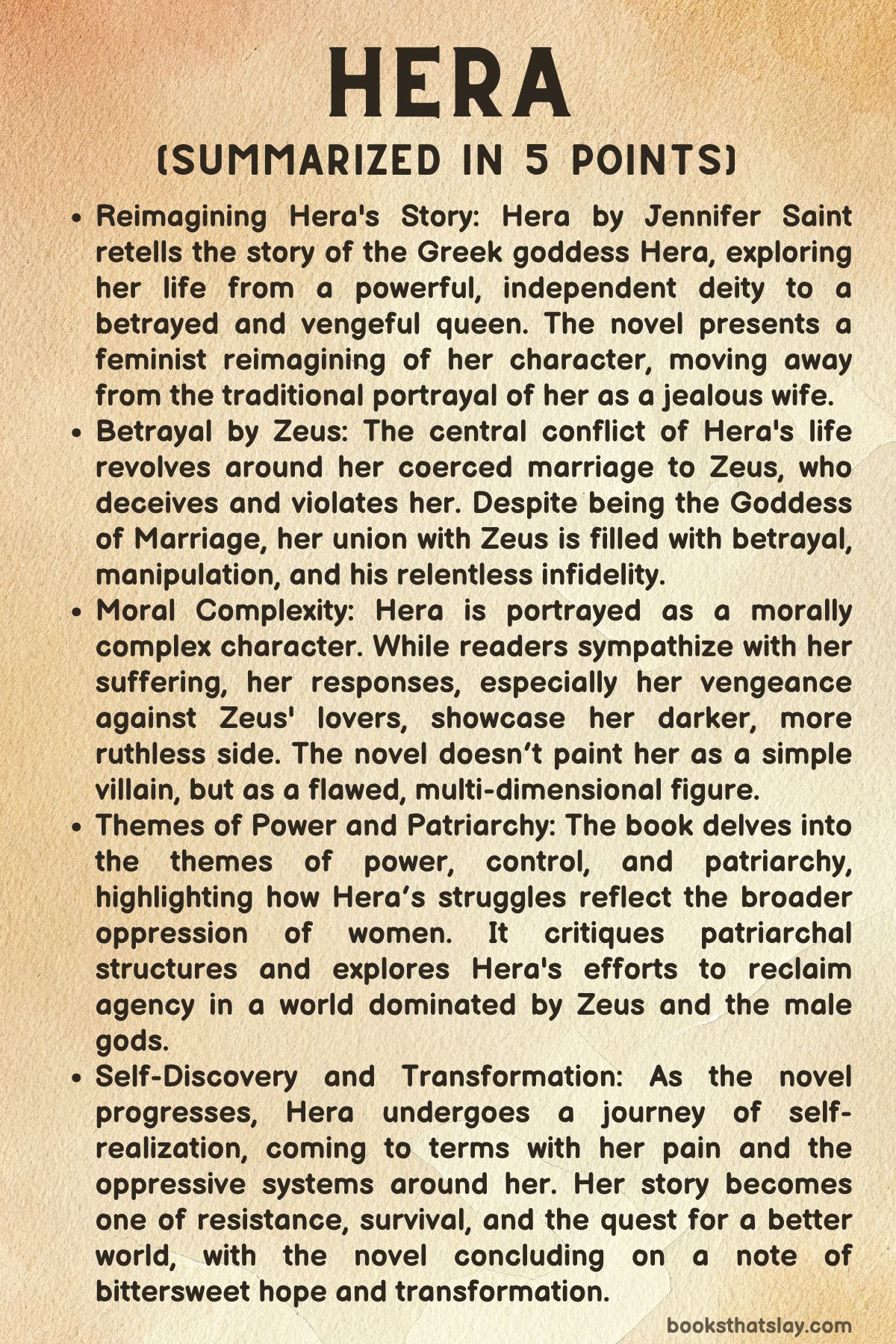

Hera by Jennifer Saint is a retelling of the mythological story of Hera, the Queen of the Gods in Greek mythology. This novel presents Hera in a fresh, complex light, exploring her journey from a powerful goddess to a betrayed wife and vengeful figure.

Saint reimagines Hera’s life, delving into her relationships with the gods, mortals, and her own internal struggles. By offering a feminist perspective, the novel highlights Hera’s fight against patriarchy, her tumultuous marriage to Zeus, and her battle to reconcile her desire for power with her personal values. The book paints Hera not as a simple villain but as a multi-dimensional and tragic heroine.

Summary

Hera follows the life of the goddess Hera, exploring her origins, rise to power, and the challenges she faces within the world of Greek mythology. Born as a powerful deity with a destiny to rule, Hera’s early days in the cosmos are marked by her strength, independence, and connection to nature.

As the daughter of Cronos and sister to Zeus, Hera is part of a world embroiled in conflict, particularly the Titanomachy, the war between the Titans and Olympians. Throughout the war, Hera emerges as a formidable figure, fiercely loyal to her family and the Olympian cause.

However, Hera’s life takes a darker turn when she encounters Zeus. Disguised as a wounded bird, Zeus deceives and violates Hera, leading to her coerced marriage with him.

Despite being the Goddess of Marriage, this union is far from ideal. Her marriage to Zeus, while politically significant, is marred by infidelity and manipulation. Zeus’ relentless affairs with mortals and goddesses deepen Hera’s resentment and bitterness, making her an emblem of a woman wronged by the very institution she represents.

The novel portrays Hera’s emotional journey, capturing her pain and the inner turmoil that comes from being forced into a marriage she neither desired nor consented to. Zeus’ constant betrayals and his disregard for her feelings lead to Hera’s complex response.

While she is betrayed by her husband, she finds herself punishing the women he victimizes rather than confronting Zeus directly. This reflects the oppressive societal norms that govern her existence as a goddess in a patriarchal world.

The narrative also offers a critical view of Hera’s reaction to her own role in perpetuating the very system that oppresses her.

The story does not shy away from showing Hera’s complexities. As the narrative unfolds, Hera’s jealousy grows, especially when Zeus’ affairs result in the births of children she feels should be hers to mother.

The birth of Athena, from Zeus’ head after he swallows Metis, further enrages Hera, who feels robbed of her maternal role. The myth of the birth of Apollo and Artemis also showcases Hera’s relentless bitterness, as she attempts to prevent the birth by cursing the land and refusing to allow Leto a place to give birth. Despite her efforts, the twins are born, fueling Hera’s jealousy further.

Hera’s involvement in key myths such as the Argonauts’ quest and the Trojan War reveal her ongoing struggle with Zeus.

Her meddling in mortal affairs during the Trojan War, driven by her grudge against Paris, who did not choose her as the most beautiful goddess, exemplifies her deep-seated anger and frustration. At the same time, Hera’s relationships with other figures, like her sister Hestia, the nurturing goddess of the hearth, and the monstrous Echidna, further deepen her character.

These relationships underscore her capacity for both empathy and cruelty, as she navigates the tensions between motherhood, power, and vengeance.

As the novel progresses, Hera grapples with her identity.

She is trapped between her divine duties and her personal desires, constantly struggling to reconcile her longing for a world of equality and justice with the realities of her role in a patriarchal Olympus. Her complex relationship with her children, particularly her son Hephaestus, who is rejected by Zeus due to his deformity, adds to her pain and bitterness.

In the end, Hera’s journey is one of self-realization. She becomes increasingly aware of the oppressive systems around her, and her story becomes a struggle for survival, resistance, and the reclamation of her identity.

The novel concludes with a bittersweet ending, showing Hera’s emotional evolution as she seeks to transcend her pain while facing the cyclical nature of power and suffering in the world of the gods.

The story resonates with feminist themes, emphasizing the endurance and resilience of women who endure patriarchal oppression, offering readers a new, more nuanced understanding of this iconic Greek goddess.

Characters

Hera

Hera is the central character in Jennifer Saint’s novel, and her portrayal is complex and multifaceted. Traditionally seen in mythology as a jealous wife and a victim of Zeus’s infidelities, the novel reframes her as a powerful and tragic figure.

Initially, she is depicted as a free-spirited and independent goddess, enjoying her divine powers and taking part in important events like the Titanomachy, the war between the Titans and Olympians. Hera is shown as loyal, ambitious, and deeply committed to the cause of the Olympians.

However, her story takes a darker turn after her traumatic encounter with Zeus. In the novel, Zeus deceives and rapes her, a pivotal event that marks the beginning of Hera’s deep sense of betrayal and emotional turmoil.

Despite this violation, Hera is coerced into marrying Zeus, which sets the stage for the power struggles that define much of her character’s journey. Hera’s character is driven by a desire for respect, control, and loyalty, yet she is continuously undermined by Zeus, whose infidelities and manipulation leave Hera feeling helpless and furious.

Her marriage becomes a cruel mockery of the values she represents as the Goddess of Marriage. Throughout the narrative, Saint shows how Hera’s anger and frustration are often misdirected. Instead of confronting Zeus, Hera often punishes the mortal women he deceives or assaults, showcasing the deep patriarchy and oppressive systems at play.

The novel paints Hera as morally complex; her vengeance can be harsh, but it is rooted in her trauma and a longing for power in a world dominated by men. As Hera grows more aware of the patriarchy that confines her, she begins to grapple with the implications of her actions and the wider structures of oppression around her.

Her internal conflict between rage and self-preservation becomes a central theme of the novel. The portrayal of Hera’s relationship with motherhood, especially with her children like Ares and Hephaestus, further complicates her character.

Her maternal instincts are often at odds with her anger toward Zeus and her frustration with the treatment of her children. Hera’s journey is one of self-discovery, as she attempts to reconcile her desire to protect her children and her own dignity in a world that undermines both.

Zeus

Zeus, the King of the Gods and Hera’s husband, is portrayed as the primary antagonist in Hera’s story. He is a manipulative and deceitful god, using his power to control and undermine Hera, despite their shared rule over Mount Olympus.

In the novel, Zeus’s treatment of Hera is rooted in his desire for dominance, as he repeatedly subjects her to betrayal through his numerous affairs with both mortal and divine women. His infidelities are not just acts of lust but also ways in which he asserts his power, diminishing Hera’s authority and causing her deep emotional harm.

His role in Hera’s trauma is pivotal, as he forces her into marriage following his violent act of deception. While Zeus is undoubtedly a powerful figure in Greek mythology, in this retelling, his character is primarily seen through the lens of his mistreatment of Hera, positioning him as a symbol of unchecked patriarchal power.

Zeus’s actions also demonstrate his emotional distance and indifference to the suffering he causes. He is presented as cold and strategic, using Hera as a political ally while undermining her in private.

This complexity adds to the moral ambiguity of the story, where Zeus’s actions are not merely those of a villain but those of a god who believes he is entitled to control those around him. His manipulation of Hera is relentless, and he remains largely unaccountable for the pain he causes.

His relationship with Hera is marked by a dynamic of power imbalance, making him a deeply troubling character whose influence stretches across the divine world.

Hephaestus

Hephaestus, Hera’s son, has a tragic and misunderstood role in the narrative. Born deformed, Hephaestus is rejected by his mother in many versions of the myth, but the novel explores their strained relationship in more depth.

In this retelling, Hephaestus is portrayed as a victim of both divine cruelty and maternal rejection. His deformity makes him an outcast, and in some ways, his treatment by Hera mirrors the injustice and suffering she herself endures.

Their relationship is one of emotional conflict. Hera’s complex feelings about Hephaestus highlight her own vulnerabilities as a mother.

Her harsh treatment of him is rooted in her frustration with her inability to protect her children from the oppressive forces at play in their world, and it serves as a poignant reflection of her emotional struggles. Despite the neglect and abuse Hephaestus suffers, he remains a tragic and sympathetic figure, misunderstood by both gods and mortals.

His experiences resonate with Hera’s own internal battles as she grapples with her dual role as a powerful goddess and a mother who is emotionally and physically scarred. The novel suggests that both mother and son are products of a patriarchal system that offers them limited agency, and the difficult relationship between them is a reflection of this shared struggle.

Ares

Ares, the god of war and Hera’s son, also plays an important role in the narrative. He is depicted as powerful and ambitious, but also overshadowed by other gods who hold more sway in the Olympian hierarchy.

In the novel, Ares becomes a source of tension for Hera, as she struggles with her desire to protect him while also dealing with the pain caused by her fractured relationship with Zeus. Ares embodies the harsh realities of war and violence, yet his relationship with his mother reveals deeper emotional layers.

Like Hephaestus, Ares is a character who suffers under the weight of his divine heritage, struggling to find his place in a world that values strength and dominance over empathy and strategy. Ares’s interactions with Hera highlight her internal conflict as a mother.

She struggles with her maternal instincts, particularly when it comes to her sons, who are affected by the very systems of power and violence that she despises. His portrayal in the novel further explores Hera’s emotional complexity, as she contends with the contradiction between her own power and the limitations placed upon her by her relationship with Zeus.

Dionysus

Dionysus, the god of wine and revelry, stands out as a more sympathetic male figure in Hera’s life. Their relationship is complicated, as Dionysus is a victim of Hera’s wrath in earlier myths, but in this novel, his relationship with Hera is more nuanced.

He is portrayed as a tragic figure, a god who suffers due to Hera’s actions yet gains her respect over time. His character challenges the typical dynamic of male gods in Greek mythology, as he is not merely a source of conflict but a character who provides a counterbalance to the other male figures in Hera’s life.

Dionysus’s relationship with Hera adds depth to her character, highlighting her capacity for respect and admiration despite her emotional turmoil and vengeful actions.

Hestia and Echidna

Hestia, the goddess of the hearth, serves as a foil to Hera. She represents peace, stability, and compassion, contrasting with Hera’s vengeful nature. Hestia’s gentleness is a source of comfort for Hera, reminding her of the potential for nurturing and harmony in a world dominated by violence and power struggles.

In contrast, Echidna, the monstrous mother of many creatures, offers a different kind of maternal empathy. Saint humanizes Echidna, showing her as a mother who, like Hera, is fighting to protect her children. The portrayal of Echidna adds a layer of complexity to Hera’s journey, as she identifies with the monstrous mother’s struggles and understands her desire to protect her family from the hostile world around them.

Themes

Feminism and Patriarchy in a Divinely Shaped World

One of the most prominent and central themes of Hera by Jennifer Saint is the exploration of the oppressive patriarchal systems that shape not only mortal society but also the lives of the gods. Hera’s narrative is deeply intertwined with feminist critiques, examining how the goddess, despite her immense power, is constantly subject to the whims of a patriarchal world ruled by Zeus.

Hera, as a goddess of marriage and family, embodies the very ideals of loyalty and fidelity, yet her own marriage becomes a cruel paradox, forcing her into a submissive role that mirrors the inequalities women experience in human society. Saint paints Hera as a victim of the systemic violence that men, especially Zeus, perpetuate.

Despite her power, Hera is undermined by Zeus’ constant infidelities, positioning her in a cycle where her anger is often misdirected, punishing other women instead of the root cause—the very patriarchal system that undermines her at every turn. This portrayal resonates with real-world issues of women being blamed for their responses to male violence, while the perpetrators remain unaccountable.

As the novel progresses, Hera’s journey becomes a critique of the inability of even the most powerful women to escape the constraints of a male-dominated society, making the story’s feminist lens particularly poignant and timely.

Power, Control, and the Complex Dance of Domination in Hierarchical Systems

Another significant theme in Hera is the intricacies of power and control, particularly in the context of relationships and the broader hierarchical structure of the gods. Hera, despite her status as Queen of the Gods, is constantly at the mercy of Zeus’ actions, which makes her struggle for autonomy and respect a central focus of the narrative.

Saint explores how power in the divine world is not simply about strength or influence, but also about how those in power manipulate relationships to maintain control. Hera’s marriage to Zeus represents the ultimate symbol of this power imbalance—she is the goddess of marriage, yet her own marital relationship is fraught with deceit, manipulation, and emotional torment.

Zeus, as the ultimate patriarch, wields his power in ways that undermine Hera’s agency, yet she responds with her own forms of control, whether through vengeance or the strategic deployment of her influence. However, her attempts to reclaim power are constantly challenged, showcasing the cyclical nature of power in patriarchal systems, where the victim often becomes the aggressor.

Saint’s exploration of power is multifaceted, illustrating that control in these systems is not always about domination; it is also about survival and the complex dynamics that emerge when one attempts to assert autonomy within a world designed to suppress it.

The Psychological Turmoil of Betrayal, Vengeance, and Self-Doubt in a Divine Context

In Hera, the theme of betrayal, vengeance, and the psychological consequences of subjugation takes center stage as the narrative delves into the goddess’ emotional journey. Hera’s personal suffering begins with Zeus’ deceitful actions, particularly the trauma of being violated and coerced into marriage.

This traumatic event sets in motion a series of emotional and psychological responses that shape her character throughout the novel. Rather than presenting Hera simply as a vengeful wife, Saint allows readers to explore the depth of her pain, insecurity, and internal conflict.

Hera’s attempts to assert power through vengeful acts against Zeus’ lovers and their children reflect not only her anger but also her feelings of powerlessness. She is a goddess of marriage who cannot escape the very institution she represents.

This dichotomy between her divine role and her personal experience leads to a sense of self-doubt, where Hera struggles to reconcile her identity as a victim of Zeus’ cruelty with her desire for revenge. Saint presents this internal struggle as a complex dance between the desire for justice and the emotional turmoil that comes with being caught in a cycle of anger and retaliation.

It is not simply a matter of vengeance, but of finding a way to reclaim a sense of self in a world that continuously undermines her.

Identity and the Quest for Self-Realization Amidst External Expectations

The theme of identity is intricately woven throughout Hera, as the goddess grapples with her role in a world that has assigned her certain expectations based on her gender and divine status. Hera’s struggle for self-realization is a central conflict in the narrative, especially when she is expected to embody the ideals of marriage, family, and loyalty despite the personal violations she endures.

Her sense of self is deeply fractured, as she navigates the complex intersection of her identity as Queen of the Gods and as a woman who has been wronged by her husband. The tension between these roles creates an internal conflict where Hera must constantly balance her public persona with her private desires, making her journey one of profound self-discovery.

As she begins to understand the broader implications of her suffering, particularly the systemic oppression faced by women both mortal and divine, she seeks a path to self-liberation. However, her actions often betray her ideals, as she lashes out at the wrong targets, struggling to break free from the roles she has been forced into.

Hera’s quest for self-realization is not linear; it is complicated by the forces of tradition, expectation, and her deep emotional wounds, making her a deeply human character despite her divine nature.

The Interplay of Love, Motherhood, and Maternal Sacrifice in the Context of Divine Power Struggles

Motherhood in Hera is another critical theme, one that adds depth and nuance to the goddess’ character. Despite her immense power and status, Hera’s experiences as a mother are fraught with difficulties, loss, and the painful realities of being a woman in a patriarchal society.

Saint uses Hera’s role as a mother to explore the complexity of maternal love and the sacrifices it often requires. Hera’s relationship with her children, especially her son Hephaestus, is marred by rejection and emotional distance. Hephaestus’ deformity and subsequent rejection by Zeus causes significant tension between mother and son, highlighting Hera’s struggle to balance her maternal instincts with the harsh realities of divine politics.

This conflict is further exacerbated by the societal expectations placed on her as a mother. Hera’s attempts to protect her children—whether through punishment or more subtle acts of intervention—often come into direct conflict with her broader desire for justice and autonomy.

The maternal sacrifices she makes, particularly in the face of divine power struggles, underscore the paradoxes inherent in her role. Hera’s motherhood is portrayed as a deeply emotional and painful experience, one that speaks to the broader theme of the ways in which women’s bodies, lives, and choices are manipulated by external forces in the pursuit of power and control.

A Modern Feminist Reinterpretation of a Timeless Myth

Jennifer Saint’s retelling of Hera’s story through a modern feminist lens brings a fresh and relevant perspective to the ancient myth. While Hera is traditionally portrayed as a jealous, vengeful figure, Hera reimagines her as a complex and multifaceted character who reflects the emotional and psychological struggles of women throughout history.

The novel does not seek to simplify her character but instead delves deep into the contradictions and nuances that make her both relatable and formidable. Saint embraces the moral complexity of Hera, presenting her as neither wholly good nor entirely evil but as a goddess whose actions are shaped by her experiences, emotions, and the oppressive systems in which she exists.

The narrative also raises critical questions about the nature of villainy, victimhood, and agency, challenging readers to reconsider the traditional portrayals of mythological figures. By highlighting Hera’s emotional vulnerability and moral ambiguity, the novel encourages readers to see her not as an archetype of cruelty but as a reflection of the very real, often contradictory experiences of women who are trapped in systems that demand compliance while simultaneously punishing them for their responses to injustice.

In doing so, Hera becomes a powerful commentary on the resilience, complexity, and resistance of women throughout history, showing that the struggles faced by mythological figures are not so far removed from those faced by women in contemporary society.