History Lessons by Zoe B. Wallbrook Summary, Characters and Themes

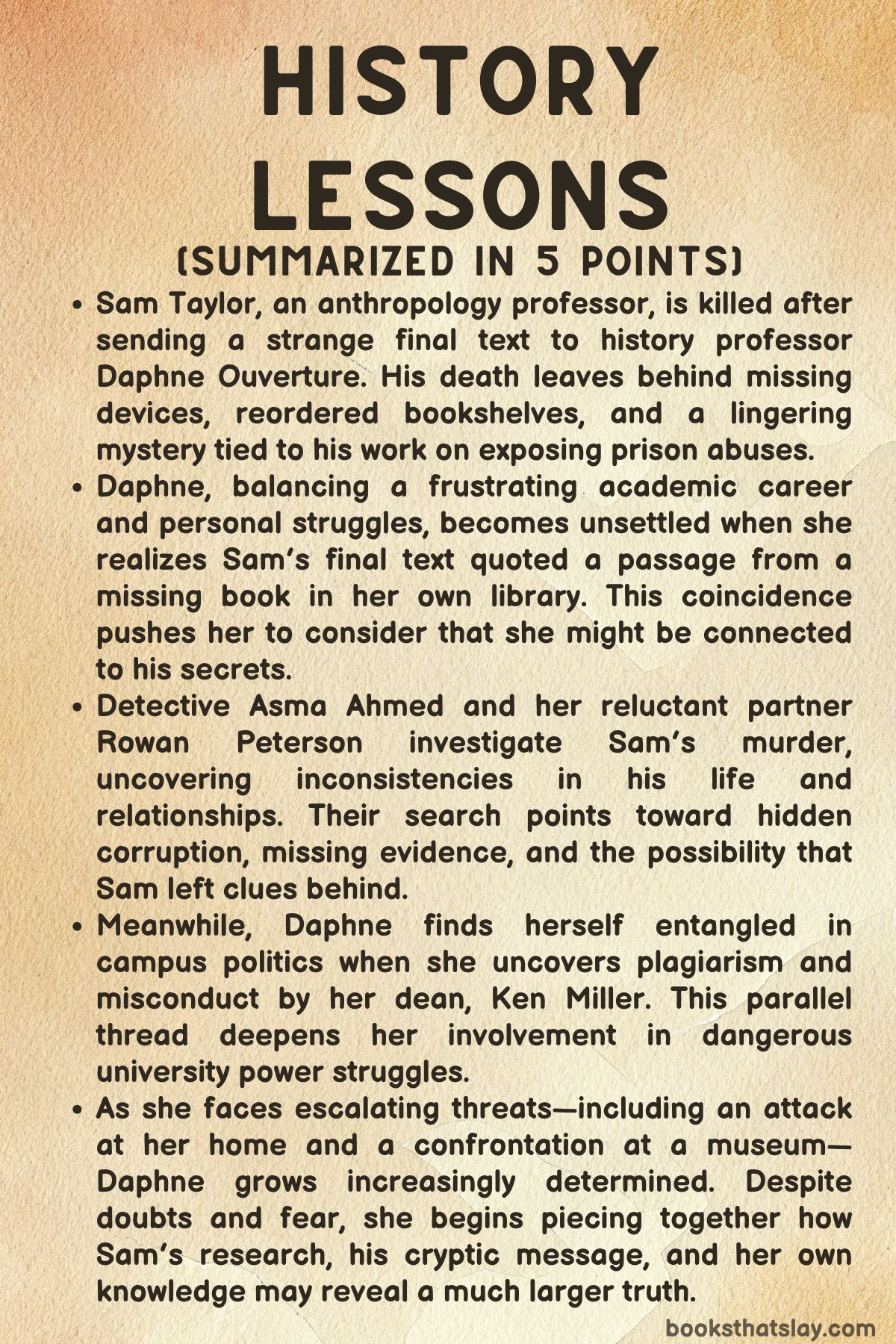

History Lessons by Zoe B. Wallbrook is a suspenseful academic thriller that explores the hidden dangers lurking beneath the polished veneer of university life. At its center is Daphne Ouverture, a young history professor whose quiet academic existence is shattered when she becomes entangled in the violent aftermath of a colleague’s murder.

As she navigates professional rivalries, institutional corruption, and personal betrayals, Daphne uncovers a dangerous web of secrets tied to both her campus and the outside world. Balancing her pursuit of truth with the risks it brings to her career, friendships, and life, the novel blends mystery with reflections on power, justice, and survival.

Summary

The story opens with the sudden death of Sam Taylor, an anthropology professor at Harrison University. Cornered in his home by unknown assailants, Sam desperately deletes files, tries to call allies, and finally manages to send a cryptic text message in broken French before being killed.

His final actions and the mystery of his missing phone set the stage for the investigation that follows.

The next perspective belongs to Daphne Ouverture, a young history professor struggling with academic isolation and a disappointing personal life. After enduring another failed date, she discovers multiple missed calls from Sam and eventually receives his strange final message.

Although she dismisses it at first, the words linger in her mind, especially when news breaks the next day that Sam has been murdered.

Detective Asma Ahmed takes charge of the investigation and reluctantly calls in her former partner Rowan Peterson, now a bookseller but once a police officer. Together, they examine Sam’s home and find inconsistencies: his phone is missing, and his meticulously organized books have been subtly disturbed.

His fiancée Molly Henderson, a powerful figure at the university from a wealthy family, found the body. Her presence and influence guarantee pressure to solve the case quickly.

Meanwhile, Daphne continues to be unsettled by Sam’s final message. When she realizes it quotes from Papillon, a memoir of imprisonment, she is alarmed to find that her own copy of the book has vanished from her shelves.

Her unease deepens when she learns Sam had been investigating abuses at a local prison, exposing corruption and human rights violations. The cryptic message and missing book suggest he left her a trail to follow.

As Daphne is pulled further into the mystery, she also becomes entangled in departmental politics. She discovers that Ken Miller, the manipulative interim dean, plagiarized the work of an African graduate student, Kiki Ilunga.

Pressured by her colleague Miranda, Daphne sneaks into Miller’s office and uncovers incriminating emails that hint he blackmailed the previous dean into resigning. Her actions nearly expose her, and she collides with Rowan outside Miller’s office, who is now assisting the murder investigation.

While balancing teaching, friendship, and academic duties, Daphne cannot escape the danger surrounding her. She is assaulted outside her own home and later hospitalized after a second violent attack.

Police find her house ransacked, her books shredded, and it becomes clear others are also hunting for the missing evidence Sam left behind. Though Detective Ahmed remains skeptical, Rowan encourages Daphne to trust her instincts, suggesting Sam deliberately entrusted her with the key to uncovering the truth.

Through her own research and connections, Daphne begins piecing together Sam’s involvement with prison corruption. At the same time, she learns unsettling truths about his personal life.

Once admired, Sam is revealed to have harassed women and abused his authority as a professor. Students and colleagues gradually admit to his arrogance and inappropriate behavior, with one student, Cassidy Reid, bravely confiding to Daphne that he assaulted her.

These revelations shift the narrative: Sam’s murder is not only about silencing his research but also tied to his predatory behavior.

Daphne’s investigation leads her to the Benson Art Museum, where she believes Sam may have hidden the incriminating video evidence. Pursued by hired men, she narrowly escapes after a violent confrontation, aided by Rowan.

Their growing closeness provides a fragile thread of comfort amid the chaos. Detective Ahmed interrogates captured guards from the prison, linking their crimes to Andrew Westmount, a wealthy benefactor with ties to the abuses.

Though Westmount is indicted, doubts remain about whether he was truly responsible for Sam’s murder.

The focus then shifts back to Molly Henderson, Sam’s fiancée. At first appearing as a grieving partner, she eventually emerges as central to the truth.

Daphne notices inconsistencies in Molly’s alibi, particularly a clue on her phone, and confronts her. Drawing on her historical expertise and her own family’s experiences with trauma, Daphne pushes Molly into confessing.

Molly admits she killed Sam after discovering his assault on Cassidy. Furious and betrayed, she struck him with a meat hammer.

Though she framed it as justice for his victims, her confession also reveals self-interest in protecting her career and reputation.

Detective Ahmed ensures Molly’s arrest, but public opinion is divided: some see her as a vigilante, others condemn her privilege and the violence she committed. For Daphne, the truth brings a mix of relief and grief.

Sam’s victims are shielded from exposure, but his actions are finally acknowledged. The fallout reshapes the university, with Miranda stepping into the dean’s role and Daphne’s own tenure secured.

In the aftermath, Daphne begins cautiously building a relationship with Rowan. Their bond grows over shared interests in books and quiet moments of companionship.

As she prepares to take up a research grant in France, they agree to maintain their connection through an exchange of books, starting their own symbolic library together. Months later, settled in Marseille with her dog Chloe, Daphne receives a gift from Rowan: a signed first edition of The Bluest Eye.

The gesture affirms both hope for her future and the endurance of their connection across distance.

Through Daphne’s journey, the novel highlights not only the dangers of corruption and abuse within institutions but also the resilience required to confront them. By uncovering both academic misconduct and personal violations, she forces hidden truths into the open, ensuring justice—even at great personal cost.

Characters

Sam Taylor

Sam Taylor, the anthropology professor at Harrison University, is introduced as a man with secrets and an underlying duplicity that comes to light after his death. Publicly, he appears to be a dedicated academic, engaged in exposing human rights abuses at Livington Prison, yet his private life reveals a more sinister side.

While admired by neighbors and colleagues for his charisma, he also displayed arrogance, inappropriate behavior, and predatory tendencies, particularly toward women such as Daphne and Cassidy. His fixation on Daphne, evident in the photos he secretly took of her, casts him in a darker light, revealing that his professional pursuit of justice was deeply entangled with his personal obsessions.

His murder sets the narrative in motion, and the contradictions within his life—between victim, activist, predator, and obsessive—make him a complex catalyst for the story’s exploration of power, corruption, and trust.

Daphne Ouverture

Daphne Ouverture, the young history professor, is at the heart of History Lessons, embodying both vulnerability and resilience. Initially weary of academia and struggling with personal loneliness, she is reluctantly pulled into a dangerous web after Sam’s cryptic message reaches her.

Her intellectual sharpness, particularly her gift for recognizing prose, becomes both a weapon and a burden as she unravels mysteries tied to Sam’s work. Daphne evolves from a hesitant participant in the investigation to a determined seeker of truth, refusing to be silenced by intimidation, assault, or institutional pressures.

Her encounters with corruption, predation, and misogyny—both in academia and beyond—force her to confront trauma while forging her path toward empowerment. Her relationships with friends Elise and Sadie ground her, while her growing bond with Rowan suggests the possibility of trust and renewal.

Daphne emerges as a layered figure: a scholar navigating systemic injustice, a survivor facing personal danger, and ultimately, a woman reclaiming agency in the face of fear.

Detective Asma Ahmed

Detective Asma Ahmed serves as both a voice of reason and a mirror of skepticism throughout the investigation. Balancing her demanding police work with family responsibilities, she embodies pragmatism and emotional restraint.

Her initial dismissal of Daphne’s theories reflects her cautious, by-the-book approach, but her persistence and keen instincts gradually uncover deeper layers of Sam’s death and the corruption surrounding it. Ahmed’s sharpness in interrogation, especially her manipulation of suspects like Gavin Gray, highlights her tactical brilliance.

Yet she is not immune to doubt, especially when evidence against Andrew Westmount feels less conclusive. Ahmed represents institutional authority, but her evolving respect for Daphne’s insight reveals her openness to unconventional perspectives.

She is a character grounded in both discipline and moral struggle, embodying the challenges of justice in murky ethical terrain.

Rowan Peterson

Rowan Peterson, the ex-cop turned bookseller and police consultant, stands at the crossroads of intellect and intuition. Tall, bookish, and enigmatic, Rowan contrasts with the rigidity of his former profession, bringing both empathy and insight to the case.

His support of Daphne, especially when others dismiss her, marks him as both confidant and potential romantic partner. Rowan’s shared love of books forms a symbolic bond with Daphne, suggesting that literature and memory serve as anchors amid chaos.

His protective presence offers reassurance, but he never overshadows Daphne’s agency; instead, he validates her instincts, reinforcing her pursuit of truth. The blossoming romance between Rowan and Daphne is not a mere subplot—it underscores themes of trust, companionship, and resilience in the face of betrayal and violence.

Molly Henderson

Molly Henderson, Sam’s fiancée and a powerful university administrator, is a character of complexity and contradiction. Outwardly, she embodies success, wealth, and institutional authority, presenting herself as a champion of women’s empowerment through her institute.

Beneath this facade, however, lies her inner turmoil: a history of familial trauma, betrayal by Sam, and the eventual burden of his violent death. Molly’s arc culminates in her confession that she killed Sam upon discovering his assault on Cassidy.

Her act blends personal vengeance with moral outrage, though it is tainted by self-interest and the preservation of her reputation. Molly is neither a simple villain nor a hero; she embodies the blurred lines between justice, privilege, and survival.

Her choices force the reader to grapple with the complexities of accountability, protection, and power.

Ken Miller

Ken Miller, the manipulative interim dean, represents the darker side of academia’s power structures. Self-serving and duplicitous, Miller embodies institutional rot through plagiarism, favoritism, and the exploitation of vulnerable students.

His theft of Kiki Ilunga’s work and his sabotage of women’s careers reveal both intellectual dishonesty and systemic misogyny. Miller’s paranoia and eventual downfall reflect the consequences of unchecked ambition, but his role also illustrates how figures like him perpetuate cycles of exploitation within universities.

His confrontations with Daphne sharpen the story’s critique of corrupt leadership, positioning him as a cautionary emblem of privilege and abuse within higher education.

Elise and Sadie

Elise and Sadie, Daphne’s closest friends, provide humor, warmth, and solidarity amid the darkness of the narrative. Both professors themselves, they act as her anchors, offering counsel, comfort, and the occasional push toward bravery.

Their banter and fierce loyalty balance the heaviness of the unfolding mystery, showing the power of female friendship in navigating hostile environments. While they are not central to the investigation, their unwavering support highlights the necessity of chosen family in moments of crisis.

Through Elise and Sadie, the novel underscores that resilience often springs not only from individual strength but also from communal care.

Cassidy Reid

Cassidy Reid is one of the most poignant figures in the novel, representing the silenced victims whose truths are often buried by institutional power. A young student assaulted by Sam, Cassidy’s hesitance to report him reflects the pervasive fear and futility many survivors face.

Her eventual trust in Daphne marks a turning point, both in the narrative and in Daphne’s own commitment to justice. Cassidy’s testimony complicates perceptions of Sam and ultimately leads to Molly’s unraveling.

Though her role is not expansive, Cassidy’s presence grounds the story’s exploration of abuse and the importance of breaking cycles of silence.

Andrew Westmount

Andrew Westmount, a wealthy powerbroker tied to the prison abuses, embodies systemic corruption at its most entrenched. His orchestration of violent crimes and embezzlement underscores the novel’s critique of institutionalized exploitation.

Though initially charged with Sam’s murder, his denial and the ambiguity surrounding his role in Sam’s final hours complicate the case. Westmount’s eventual imprisonment and violent stabbing serve as both a form of justice and a reminder of the dangerous entanglements between money, power, and brutality.

He stands as a chilling reminder that while individuals like Sam or Molly may dominate personal storylines, larger systems of power often remain deeply corrosive.

Themes

Power and Corruption within Institutions

In History Lessons, the persistent theme of corruption in academic and state institutions shapes much of the narrative. The story underscores how positions of authority—whether in a university or within the justice system—are vulnerable to exploitation.

Figures such as Ken Miller embody the dangers of unchecked ambition, using plagiarism, manipulation, and intimidation to advance his career, while simultaneously silencing or destroying the reputations of others. The university, ostensibly a place of intellectual growth and fairness, becomes instead a site of power games and concealed abuses.

This corruption is not isolated to academia; Sam Taylor’s investigation into Livington Prison exposes institutionalized violence and the systematic denial of human rights. The prison, like the university, thrives on concealment and complicity, showing how systems protect perpetrators rather than victims.

Both settings reveal the disturbing overlap of personal ambition and systemic abuse, where truth becomes dangerous currency. The novel demonstrates how institutional corruption is not abstract but deeply personal, leaving victims vulnerable and creating cycles of fear, silence, and mistrust.

Gender, Exploitation, and Resistance

The novel gives powerful attention to the way women experience both vulnerability and resilience in patriarchal spaces. Characters like Daphne, Cassidy, and Molly navigate environments rife with exploitation, where their academic and personal lives are shaped by the abuses of men in positions of power.

Sam’s predatory behavior illustrates how charisma and status can be weaponized against younger women, turning mentorship into manipulation. Cassidy’s silence reflects the fear of disbelief and retaliation, a fear echoed in Daphne’s decision to initially conceal Sam’s obsession with her.

Yet the narrative also explores forms of resistance. Molly’s act of killing Sam, though morally complicated, reflects an eruption of rage against predation and betrayal, forcing recognition of injustices previously hidden.

Daphne’s persistence in uncovering the truth, despite threats to her safety and career, reinforces the idea that resistance is not always grand but often a steady act of refusing silence. The novel situates gendered violence not as isolated acts but as structural problems, where survival requires solidarity, courage, and the willingness to confront uncomfortable truths.

Truth, Memory, and the Burden of History

The novel’s title itself directs attention to the weight of history—not only the formal study of the past but also the personal histories that characters carry. Daphne’s profession as a historian makes her especially attuned to memory, documentation, and the ways stories are preserved or erased.

Sam’s cryptic message referencing Papillon demonstrates how literature becomes a vessel for truth, a hidden archive waiting to be interpreted. Yet truth in this novel is not clear-cut.

Sam is both a victim of murder and a perpetrator of abuse, complicating the way his “legacy” is remembered. The burden of exposing his crimes falls on Daphne, who must balance her duty to history with her responsibility to living survivors.

History here is not neutral; it is shaped by who controls the narrative and what evidence survives. The novel suggests that remembering accurately is itself an act of justice, even when that truth destabilizes institutional reputations or personal comfort.

Daphne’s eventual decision to honor the voices of Sam’s victims illustrates how history is not just about the past but about the present choices of who speaks and who is silenced.

Justice, Morality, and Ambiguity

Justice in History Lessons is never straightforward. The novel raises pressing questions about what justice means when systems themselves are corrupt.

Detective Ahmed embodies this tension—committed to law and order, yet frequently aware that official justice may fall short of moral justice. Molly’s killing of Sam epitomizes the ambiguity: is it retribution, protection, or simply another abuse of privilege?

Similarly, the exposure of Westmount’s crimes brings institutional accountability, yet even then violence persists, as shown in his stabbing while imprisoned. Daphne’s pursuit of truth positions her between formal justice and personal morality; her actions—snooping into offices, concealing information, and placing herself in danger—fall outside conventional justice but ultimately bring hidden crimes to light.

The novel suggests that justice is fractured, shaped by flawed individuals, social hierarchies, and the willingness to face hard truths. Rather than presenting tidy resolutions, it insists that justice is messy, partial, and often unsatisfying, demanding difficult moral choices from those who pursue it.

Isolation, Connection, and Personal Transformation

At the heart of the story is Daphne’s journey from isolation to connection. Initially portrayed as someone disillusioned with her career, disappointed in her personal life, and withdrawn into her books, she becomes drawn into a web of danger that forces her into contact with others.

Her friendships with Elise and Sadie offer her emotional grounding, even when they cannot fully share her burden. Rowan’s presence evolves from watchful ally to romantic partner, symbolizing the possibility of trust and renewal after betrayal.

Importantly, Daphne’s bond with Cassidy shows the transformative power of empathy and solidarity; in protecting Cassidy, she finds a renewed sense of purpose and ethical commitment. Isolation is not only Daphne’s personal state but also a broader condition of academia and survival in patriarchal structures, where silence and fear separate individuals.

Her trajectory demonstrates that connection—through friendship, trust, and love—is what enables resistance and healing. By the novel’s end, her cautious embrace of a relationship with Rowan and her pursuit of a peaceful academic life in Marseille signal not only survival but transformation, suggesting that even amid violence and corruption, personal renewal remains possible.