How Bad Things Can Get Summary, Characters and Themes

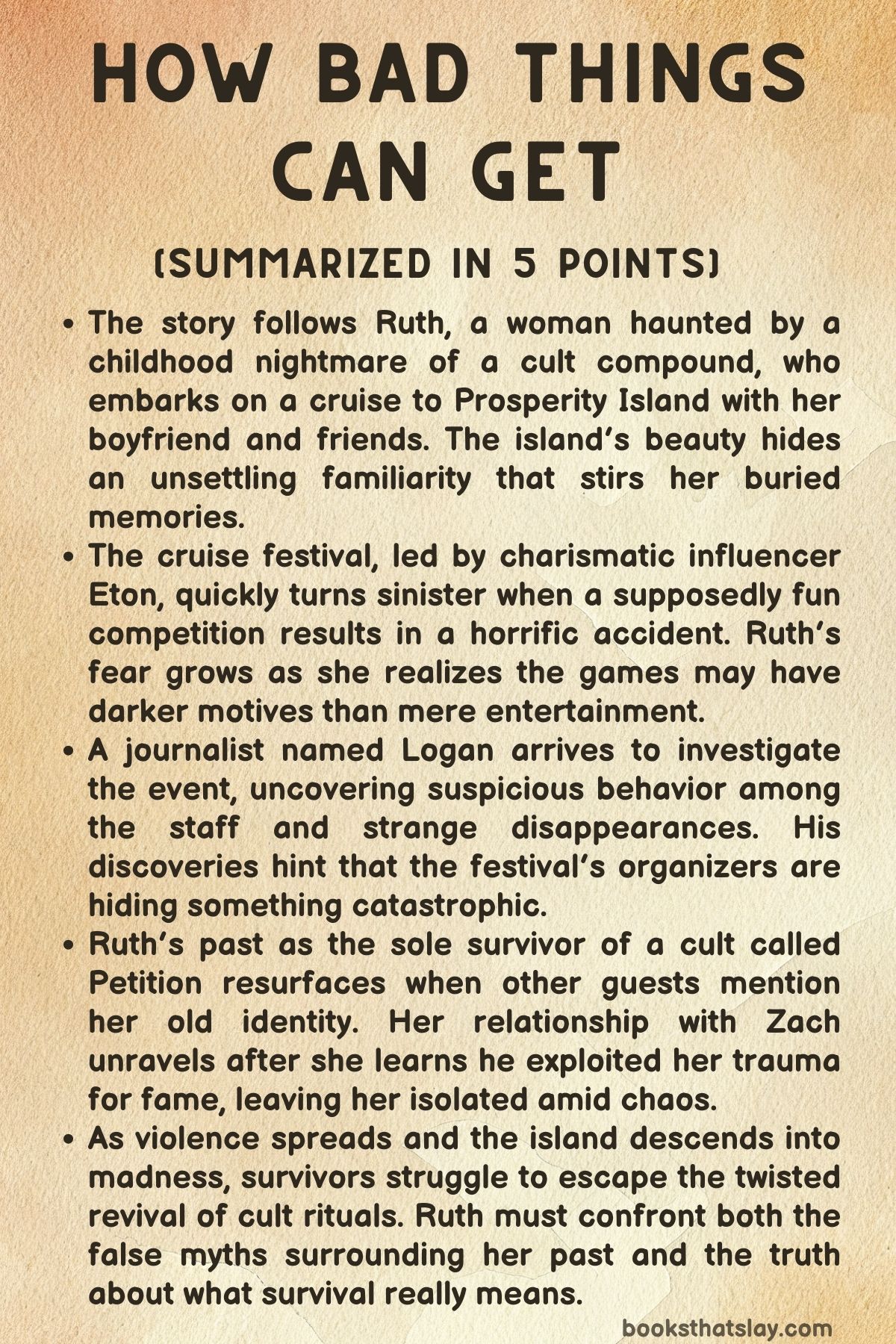

How Bad Things Can Get by Darcy Coates is a chilling psychological thriller that explores the horrifying consequences of media spectacle, trauma, and cult survival. The novel follows Ruth, a woman haunted by her past as the lone survivor of a death cult, as she becomes trapped on an island where an influencer’s grand festival descends into chaos and bloodshed.

The story blends elements of horror and suspense with an examination of exploitation and guilt, showing how the lust for entertainment and fame can mask the darkest human impulses. Coates builds dread slowly, leading to a harrowing and unforgettable climax.

Summary

The story begins with a nightmare: a young girl, Josanna, crawls through a dark compound where people have gouged out their own eyes. A menacing voice calls out, promising her death will make “it work.

” She finds no escape. Suddenly, the dream shatters, and a woman named Ruth wakes aboard a cruise ship bound for Prosperity Island.

Her boyfriend Zach and their friends Hayleigh and Carson are excited for the upcoming festival hosted by Eton, a famous influencer, but Ruth is uneasy. The island’s silhouette feels disturbingly familiar—exactly like the one in her recurring nightmares.

On the ship, Eton’s operations manager Petra struggles to organize the festival amid her boss’s reckless enthusiasm. Eton dismisses her safety concerns, determined to put on an unforgettable event.

When the passengers disembark, they’re greeted with gifts, maps, and painted stones marked with red or black circles. The red ones identify contestants for a mysterious game.

Ruth’s stone glows red—she’s been chosen.

Ruth joins the first challenge, a towering maze of beams above the ocean called Endurance Cove. The goal is to collect numbered tokens without falling.

As the game begins, the crowd cheers, but disaster strikes when a contestant, Makayla, falls from a cracked beam and lands on hidden rocks. Despite the horrific injury, Eton forces the game to continue, laughing it off as part of the show.

Ruth, traumatized, finishes the challenge but confronts him in fury afterward. Eton apologizes but minimizes the event.

That night, Ruth overhears strangers mention the name “Petition”—the same cult she escaped as a child—and panic grips her.

In the jungle, Ruth confides in Zach that she once survived the cult’s mass suicide. She worries the festival feels like a repetition of her trauma—charismatic leadership, blind obedience, isolation—but Zach assures her she’s safe.

Their talk is interrupted by alarms echoing across the island.

Meanwhile, Logan, a journalist investigating influencer scandals, sneaks through the event area. He suspects something sinister behind Eton’s festival.

He spots staff moving a large steel-blue suitcase with strange caution. When he later examines it through a window, one of the men—Barry—appears suddenly, hugging Logan and whispering cryptic threats.

As the island grows tense, Ruth’s nightmares intensify. She collapses during a meal while staff quietly block all exits, insisting guests stay put.

Logan, reviewing his photos, realizes the suitcase leaks blood. Petra tries to keep control of the situation, but Eton has disappeared.

When she finally finds him, he confesses he planned the festival as a distraction from an underage scandal he feared would destroy him. Before she can react, he reveals a corpse in the nearby tide pools.

Ruth soon learns her worst truth: Zach had betrayed her. Her friends Carson and Hayleigh confront her with the revelation that Zach used her secret past—the “Petition Child” survivor story—to win their tickets.

Ruth realizes her boyfriend was the same podcaster who once sensationalized her trauma. Before she can escape, their cabin door opens as unseen figures enter.

Chaos spreads across the island. Power fails, and the festival staff reveal their allegiance to a new cult, a distorted revival of Petition.

Ruth, Zach, and Hayleigh hide near the clinic as the cultists hunt survivors. Determined to contact help, Ruth breaks into the clinic and finds the doctors mutilated.

She locates a satellite phone and throws it to Zach. At the same time, Petra and Logan fight their way through the compound.

Petra reaches the phone, manages to make a brief emergency call, and is killed moments later as cultists overrun the area.

Ruth is captured and tied to a ritual site where Barry—the cult’s self-proclaimed leader—declares a “cleansing. ” He forces captives to drink poisoned “honey,” reviving Petition’s suicide rite.

Ships appear offshore, signaling rescue, and Barry orders the ritual to begin. The cultists anoint themselves in blood, chant, and consume the toxin.

As the poison takes hold, madness erupts: they turn on themselves and each other, dying violently. Ruth survives by spitting out the poison, recalling how she lived through the original Petition massacre as a child.

She staggers through the carnage, finding Zach dead near the shore. Cradling him, she confesses that she was never the cult’s prophetic child—just misidentified by investigators.

She watches as rescuers land and begin recovery efforts, pulling survivors from debris and documenting the horror. The world soon learns of the massacre through leaked footage and survivor accounts.

After returning home, Ruth reaches out to Logan. Tired of lies and exploitation, she removes all digital filters hiding the word “Petition” and confronts the truth of her past.

She proposes one uncut interview to tell the reality of cult life—not as myth or spectacle, but as a story of manipulation, boredom, and ordinary cruelty that led to atrocity.

The aftermath unfolds in a series of public reckonings. Authorities investigate Eton’s negligence and his role in the disaster.

Influencers and sponsors face lawsuits, and the surviving cult members are arrested. The media floods with documentaries, memoirs, and sensationalized accounts.

DNA testing identifies victims from both cult eras, confirming that history has repeated itself.

In the end, Ruth stands as a reluctant witness to the second Petition’s destruction—a survivor burdened with memory but determined to reclaim her story. How Bad Things Can Get closes not on triumph, but on Ruth’s quiet decision to expose the truth, ensuring the cycle of spectacle and violence is finally seen for what it is: the terrible cost of human obsession.

Characters

Ruth (Josanna)

Ruth stands as the emotional and psychological nucleus of How Bad Things Can Get. Haunted by recurring nightmares of a childhood massacre, she exists in a liminal space between survivor and victim.

Once Josanna—the lone child to escape the Petition cult—Ruth’s adult life is built on fragile layers of denial and reconstruction. Her trauma manifests through sensory memories: darkness, cold hallways, and whispered commands to die.

On the surface, she appears as a quiet, anxious woman trying to participate in normal social life, yet beneath that lies a well of guilt, fear, and suppressed memory. The island setting becomes an externalization of her psyche—beautiful yet treacherous, haunted by her past.

As she faces the manipulative forces of Eton’s festival and the resurgence of cult violence, Ruth undergoes an excruciating evolution. Her journey is one of reclaiming identity, moving from passivity to confrontation, from being defined by horror to defining it herself.

Her survival at the end is less a victory than an acknowledgment of endurance—the grim continuation of someone who has lived through the worst and refuses to be mythologized again.

Zach

Zach embodies both comfort and betrayal within Ruth’s fragile world. Initially portrayed as a supportive boyfriend, his gentleness provides Ruth with a semblance of normalcy.

However, the eventual revelation that he exploited her trauma for fame shatters that illusion. His actions—using her story to win entry to the island—expose the predatory underside of modern media and the voyeuristic consumption of tragedy.

Despite his genuine affection for Ruth, his obsession with the Petition case blurs the boundary between love and manipulation. Zach is a tragic reflection of how fascination with trauma can morph into exploitation.

His death on the beach, in Ruth’s arms, seals his moral collapse and underscores the novel’s recurring motif: that the desire to control or narrativize another’s pain leads inevitably to ruin.

Petra

Petra functions as the moral counterbalance to the chaos of Prosperity Island. Intelligent, weary, and overworked, she is the festival’s operations manager who recognizes the impending disaster before anyone else.

Torn between professional loyalty and ethical responsibility, Petra’s arc illustrates the limits of complicity within corrupt systems. Her attempts to impose order—whether through safety protocols or crisis management—are constantly undermined by Eton’s hubris.

As events unravel, she transforms from bureaucratic functionary to self-sacrificing savior, giving her life to send the distress call that ensures rescue. Petra’s death epitomizes the tragic cost of integrity in a world driven by spectacle and deceit, positioning her as one of the novel’s few unambiguous heroes.

Eton

Eton is the personification of performative charisma and modern narcissism. A social media influencer turned event mogul, he thrives on spectacle and manipulation, using charm to mask deep moral rot.

His obsession with audience engagement transforms suffering into entertainment, blurring the boundary between reality and performance. The festival’s games—ostensibly playful—serve as metaphors for social media’s hunger for attention, where human dignity is secondary to spectacle.

Eton’s confession about his scandal reveals the hollow desperation behind his image: a man willing to orchestrate mass distraction to erase his guilt. His downfall, when exposed and hunted by the chaos he created, completes his metamorphosis from idol to monster.

He is both a creator and casualty of the culture he embodies.

Logan Lloyd

Logan operates as both investigator and witness. A journalist and YouTuber obsessed with uncovering the truth behind influencer culture, he enters the island with cynicism but gradually becomes its chronicler of horror.

His detached professionalism gives way to genuine moral outrage as he confronts the grotesque reality of Eton’s experiment. Through Logan, the novel critiques the media’s complicity in sensationalizing trauma—he begins by exploiting it but ends by recording it truthfully.

His alliance with Petra and his survival mark him as one of the few characters capable of balancing exposure with empathy. Logan’s final role as Ruth’s correspondent—helping her reclaim her story—positions him as the novel’s conduit for truth and restitution.

Barry

Barry, the self-proclaimed heir of Barom’s cult, symbolizes the cyclical nature of fanaticism. With his grotesque grin and disturbingly intimate demeanor, he serves as both parody and continuation of the original Petition ideology.

His leadership of the island’s reborn cult highlights the ease with which belief systems resurrect themselves under new veneers of purpose. Barry’s twisted devotion to ritual and purification reveals a man enslaved by borrowed mythology.

His death amidst the poisoned congregation becomes poetic justice—he is consumed by the very madness he sought to command. Barry’s presence reinforces the novel’s warning: evil does not vanish but adapts, reshaping itself through new faces and eras.

Makayla

Makayla begins as a secondary participant in the games but emerges as a symbol of human endurance and resilience. Initially portrayed as confident and daring, her near-fatal fall exposes the cruelty beneath Eton’s orchestrations.

Though gravely injured, she reenters the narrative later, fighting for survival and assisting in the satellite rescue. Her arc represents the quiet strength of those who, though brutalized by circumstance, continue to act decisively.

Unlike Ruth, who wrestles with internal demons, Makayla’s struggle is external and physical, embodying courage and clarity in contrast to the moral murk of the others.

Hayleigh and Carson

Hayleigh and Carson operate as narrative mirrors of moral inertia. Both begin as typical vacationers, swept up in the thrill of Eton’s spectacle, their banter masking ignorance of the danger around them.

Hayleigh’s compassion for Ruth gradually deepens into fear and loyalty, while Carson’s hostility transforms into a grim recognition of his own helplessness. When the truth about Zach emerges, their reactions—anger, betrayal, and horror—underline the novel’s thematic concern with complicity.

They are ordinary people drawn into extraordinary evil, and their inability to act meaningfully reflects the paralysis of bystanders in the face of exploitation.

Mother Aama

Though physically absent from the main timeline, Mother Aama’s presence haunts the entire narrative. As the blind matriarch of the original Petition cult, she represents the weaponization of faith and the perversion of maternal authority.

Her whispered insistence that Josanna “must die” becomes an echo through Ruth’s life—a symbol of how ideology can erase individuality under the guise of salvation. Aama’s influence transcends death, manifesting through hallucination and imitation in the island’s new cult.

She is less a person than an embodiment of the human drive to dominate others through belief.

Themes

Trauma and the Haunting Power of Memory

In How Bad Things Can Get, the story operates as an unrelenting examination of how trauma imprints itself onto memory and identity, refusing to fade even when years and geography separate the survivor from the site of suffering. Ruth’s childhood as Josanna—the sole survivor of the Petition cult—casts a shadow over every moment of her adult life.

Her nightmares are not mere recollections but sensory replays of past terror: the cold, the darkness, the smell of blood. These memories shape her perception of reality, blurring the line between what is happening and what has already happened.

The cruise, meant as a vacation, becomes a stage for the resurgence of everything she has tried to suppress. Each scream, each moment of performance or manipulation, triggers a visceral response that drags her back to the cult’s compound.

The novel portrays trauma as cyclical rather than linear, showing that survival does not necessarily equate to healing. Ruth’s identity itself fractures under the pressure of remembering—she is both Ruth and Josanna, both the adult who escaped and the child still trapped in the dark.

The haunting of memory becomes both internal and external: as she realizes the island’s setting mirrors her nightmares, the landscape itself becomes an extension of her trauma. The physical space of Prosperity Island, filled with mirrors of past horrors, literalizes how trauma reclaims the present, shaping how Ruth interprets every encounter.

Through this, the book suggests that confronting the truth of one’s memories—no matter how grotesque—is the only possible path to reclaiming autonomy from them.

The Exploitation of Suffering and Media Spectacle

A core thread running through How Bad Things Can Get is the commentary on how modern entertainment and digital culture commodify pain. The festival that Eton orchestrates is presented as a perfect metaphor for the moral rot beneath influencer culture: a world where attention trumps empathy and spectacle outweighs safety.

The deadly games are staged under the guise of entertainment, their violence broadcast and cheered by onlookers who treat suffering as content. Even the tragic fall of Makayla is transformed into spectacle, her injuries minimized for the sake of the show’s momentum.

Eton, charismatic and hollow, embodies a culture that thrives on curated chaos—his charm weaponized to disguise cruelty. The audience, equally complicit, reveals society’s hunger for sensationalism and its detachment from human cost.

When Ruth’s past as the “Petition Child” becomes public knowledge, her trauma is again consumed by media narratives—podcasts, documentaries, viral interviews—all reframing her survival for clicks and profit. The novel paints this cycle as a grotesque reflection of our collective addiction to tragedy.

Every disaster becomes a story to monetize, every victim a potential celebrity. Ruth’s decision at the end to tell her unedited, unembellished version of events becomes an act of resistance against this machinery.

By reclaiming her narrative from those who would exploit it, she restores humanity to her experience and rejects the sensationalism that once defined her.

Charisma, Control, and the Anatomy of Cults

Darcy Coates exposes the mechanisms of control that underlie both religious cults and modern celebrity influence. The parallel between Barom’s Petition and Eton’s Prosperity Island is unmistakable: both are built upon manipulation, blind devotion, and the exploitation of human need.

Eton’s charm is seductive, but beneath it lies the same psychological architecture that allowed Barom to control his followers decades earlier. Both leaders depend on creating illusions of community and purpose while isolating their followers from dissent.

The shift from a spiritual cult to a social-media-driven one highlights how the form changes but the function remains constant—human vulnerability is endlessly exploitable. Petra’s role illustrates the tension between moral awareness and complicity; she recognizes the danger yet continues to serve, rationalizing her inaction as duty.

The cultists on Prosperity Island, echoing the Petition’s self-destructive zeal, reveal how belief can mutate into violence when guided by charisma and fear. The climactic ritual—followers willingly drinking poisoned “honey”—distills this dynamic into its most horrifying purity.

Even the modern guests, who arrive seeking entertainment, fall prey to collective influence, their autonomy eroded by the seductive power of spectacle. The novel suggests that cults are not confined to isolated compounds; they thrive wherever authority, performance, and collective delusion intersect.

Guilt, Identity, and the Struggle for Redemption

Ruth’s journey through How Bad Things Can Get is fundamentally about self-reconciliation. She lives under a mistaken identity, haunted not only by what happened but by how the world has interpreted it.

Society has mythologized her as a prophetic child, a survivor blessed with divine purpose, when in reality she is burdened by guilt and confusion. Her survival feels less like salvation and more like a lingering punishment—she carries the deaths of others as part of herself.

Zach’s betrayal deepens this torment; his fascination with her story transforms her into an object of curiosity, a symbol rather than a person. This realization forces Ruth to confront not only her trauma but the identity that has been constructed around her.

Redemption, for her, comes not through forgiveness or revenge but through authenticity. When she chooses to tell the truth in her own words, stripped of spectacle, she redefines survival as agency rather than endurance.

The novel’s ending, filled with both devastation and quiet defiance, presents redemption as a process of reclamation—of narrative, of selfhood, and of meaning. Through Ruth, Coates explores how guilt can evolve into strength when met with honesty, and how redemption, though fragile, begins when one stops being the subject of others’ stories and becomes the author of their own.