How to Tell a True War Story Summary, Themes and Analysis

“How To Tell a True War Story” is a story within Tim O’Brien’s novel The Things They Carried. It grapples with the difficulty of capturing the truth of war experiences.

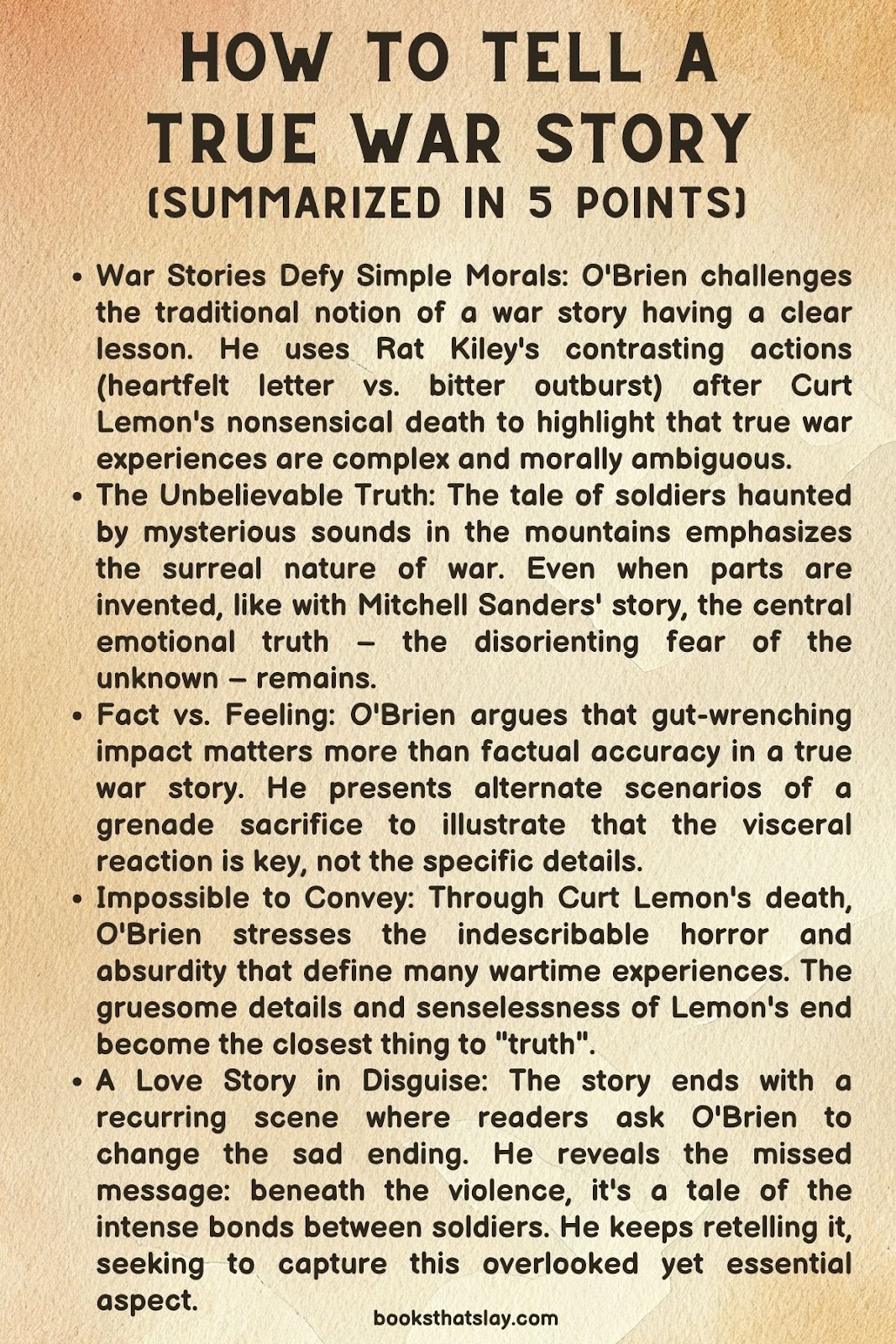

O’Brien argues a true war story can’t be boiled down to a simple moral. It’s more nuanced, like “the thread that makes the cloth.” Brutal facts like “war is hell” don’t resonate deeply enough.

The story explores this through contrasting narratives. A soldier might write a glorified letter about a deceased friend, emphasizing bravery. But the true story might be messy and complex, defying easy explanation.

O’Brien even suggests sometimes the truest stories are invented. He might tell a fictional tale of a soldier sacrificing himself for his friends, then another where they all die. The point is, the emotional truth can be stronger than factual accuracy.

Ultimately, a true war story, according to O’Brien, leaves you with a deep, unsettling feeling – a sense of the absurdity and horror of war.

Summary

O’Brien opens by declaring this story a true one, yet immediately undercuts the reader’s trust. Rat Kiley, devastated by the loss of his friend Curt Lemon, writes a glowing letter to Lemon’s sister.

He portrays Lemon as a brave war hero and speaks of their profound bond. Two months pass without a response, and Kiley descends into bitterness, calling the sister a “dumb cooze.”

The contradiction here sets the stage for what follows. O’Brien emphatically asserts that a true war story is not moral, it doesn’t try to teach a lesson.

This seemingly strange claim becomes clearer when he reveals the circumstances of Curt Lemon’s death. Far from a heroic sacrifice, Lemon died in a freakish accident during a moment of careless playfulness.

Next, O’Brien stresses that the real horror of war often lies in elements so bizarre they defy belief. He introduces Mitchell Sanders’ haunting tale of a troop sent to the mountains on a routine mission.

There, they hear strange, ethereal noises: music, voices, like a distant party. The sounds build in intensity, driving the men to paranoia.

They open fire on everything, desperately trying to destroy the source of the eerie echoes, yet the noises continue. Baffled and shaken, they retreat – and have no explanation for what they experienced.

This story is further complicated when Sanders later confesses to O’Brien that parts were fabricated.

The moral?

According to Sanders, sometimes it’s just the oppressive quiet. This sets up another central idea: the line between truth and fiction blurs in war.

O’Brien returns to Curt Lemon, describing his death briefly but vividly. After this, he circles back to the nature of truth in war stories.

A soldier may die heroically saving comrades, but does why he dove on that grenade truly matter at that moment?

Sometimes the most truthful war stories aren’t factually accurate. He illustrates this by presenting a hypothetical version of that heroic sacrifice where everyone dies anyway. One dead soldier asks the other why he jumped, and the response is a world-weary, “Story of my life, man.”

O’Brien believes a true war story is visceral. You should feel it in your gut, not analyze it in your head. Lemon’s death, an absurd tragedy, certainly fits this description.

One moment he was joking, the next he was blown into a tree. It’s the chaotic, meaningless nature of his end that lingers most. O’Brien and Jensen’s grisly task of retrieving the remains only enhances the absurdity.

War is contradictory and surreal, O’Brien argues – the exhilaration after a firefight sits alongside the crushing despair of loss.

Trying to distill this into a neat narrative with a lesson misses the point. This is why, even in true war stories, nothing is absolutely true.

The story closes with a recurring vignette. Each time O’Brien tells the story of Curt Lemon, someone (usually a woman) expresses sadness at it. They want a different, less brutal kind of story.

He wishes he could explain that at its core, despite the death, this is actually a story about love – the deep, sometimes baffling camaraderie between soldiers on the front line.

O’Brien ultimately concludes that his only recourse is to keep telling the story, perhaps embellishing it further, seeking to capture that elusive truth that makes us believe, not just understand.

Here is a complete analysis of the themes and literary devices of the novel.

Themes

The Subjectivity and Unreliability of Truth

O’Brien challenges conventional notions of “truth” in war narratives.

Rat Kiley’s embellished letter about Curt Lemon exemplifies this. Motivated by grief, he romanticizes his friend’s death, creating a palatable heroism that masks the senselessness of the event. Even the author, claiming the tale is “true,” admits that factuality does not equal emotional veracity.

Mitchell Sanders’ story of haunting sounds in the mountains, parts of it later revealed as fiction, further complicates the issue.

O’Brien argues that the emotional core, the lingering terror those sounds evoke, might be “truer” than a strictly factual retelling.

This blurring of truth and invention illustrates how memory, trauma, and the need to make sense of the nonsensical shape war stories.

The Amorality of War

“How to Tell a True War Story” defies easy moralizing.

O’Brien insists that true war stories eschew lessons in favor of conveying the stark and often brutal reality of combat. Curt Lemon’s absurd death during a playful moment illustrates this point.

The lack of meaning in his demise, contrasted with Kiley’s initial glorifying impulse, shows how war breaks down conventional standards of heroism and purpose.

Further, Kiley’s callousness toward Lemon’s sister, fueled by his unmet need for closure, showcases the warping effect war has on the human psyche. It forces soldiers into survival mode, stripping morality down to its barest form.

O’Brien’s point isn’t that soldiers are inherently bad, but that the brutal nature of war pushes actions and feelings towards uncomfortable, morally ambiguous territory.

The Difficulty and Necessity of Bearing Witness

O’Brien suggests that despite the horror and trauma, there’s a moral imperative to recount war stories.

Mitchell Sanders’ tale, even with its fabricated elements, expresses his deep need to make sense of the senseless fear he and his comrades experienced.

O’Brien, by relaying Lemon’s death, bears witness to both the absurdity and the profound loss, even if he struggles to find the perfect words to convey it. The common reaction, particularly from women, is to desire a different kind of story.

This mirrors our own inclination to distance ourselves from uncomfortable truths.

Yet, O’Brien hints that only through unflinchingly confronting the realities of war, as messy and unsettling as they may be, can we truly understand its cost and hopefully work towards a world where such stories lose their necessity.

Literary Devices

Metafiction

O’Brien constantly breaks the fourth wall, directly addressing the reader and commenting on the very act of storytelling.

He claims his story is true, then undermines that notion by exploring how truth can be subjective or even manipulated in the context of war.

He discusses the moral purpose of stories and how “true” war stories intentionally defy those expectations.

This metafictional technique makes the reader question not just the events of the story, but the very nature of how we create meaning from the chaos of experience.

Juxtaposition and Contrast

O’Brien uses jarring contrasts to highlight the absurdity and disorienting nature of war. Rat Kiley transitions from heartfelt grief over Curt Lemon to petty rage when his letter goes unanswered – a shift that mirrors the way war blurs the line between nobility and base emotions.

Vivid imagery of Curt Lemon’s gruesome death is juxtaposed with the mundane task of recovering his remains, emphasizing the grotesque ordinariness with which horrific events become absorbed into wartime life.

Paradox and Ambiguity

The story is rife with paradoxes that reflect war’s complex, contradictory nature.

“A true war story is never moral,” O’Brien declares, yet the story itself explores issues of heroism, guilt, and the struggle to make sense of senseless events.

He argues that believable war stories often contain the unbelievable, highlighting that the most absurd details might carry the greatest emotional truth.

O’Brien leans into ambiguity, leaving the reader in a place of uneasiness and unresolved tension.

Fragmentation and Repetition

The narrative is deliberately fragmented, jumping between vignettes, reflections on storytelling, and hypothetical scenarios.

This mirrors the way memory functions, especially traumatic memory, where events replay over and over, not in linear form, but in flashes of sensation.

Repetition of phrases like “story of my life” and variations on the motif of the dead soldier questioning his own actions underscore the cyclical nature of war and the difficulty of extracting any larger meaning.

Symbolism

While not relying on overt symbols, O’Brien uses objects and settings that gain symbolic weight throughout the story.

Lemon’s name itself (a bright, tart thing) contrasts with his explosive death, highlighting the randomness of fate. The oppressive silence in Sanders’ tale transforms from a neutral element into a menacing force, reflecting the unseen psychological terrors faced by soldiers.

Even the water buffalo Kiley brutalizes becomes a symbol of both enemy suffering and the men’s own descent into desensitized cruelty.