I Just Wish I Had a Bigger Kitchen Summary and Analysis

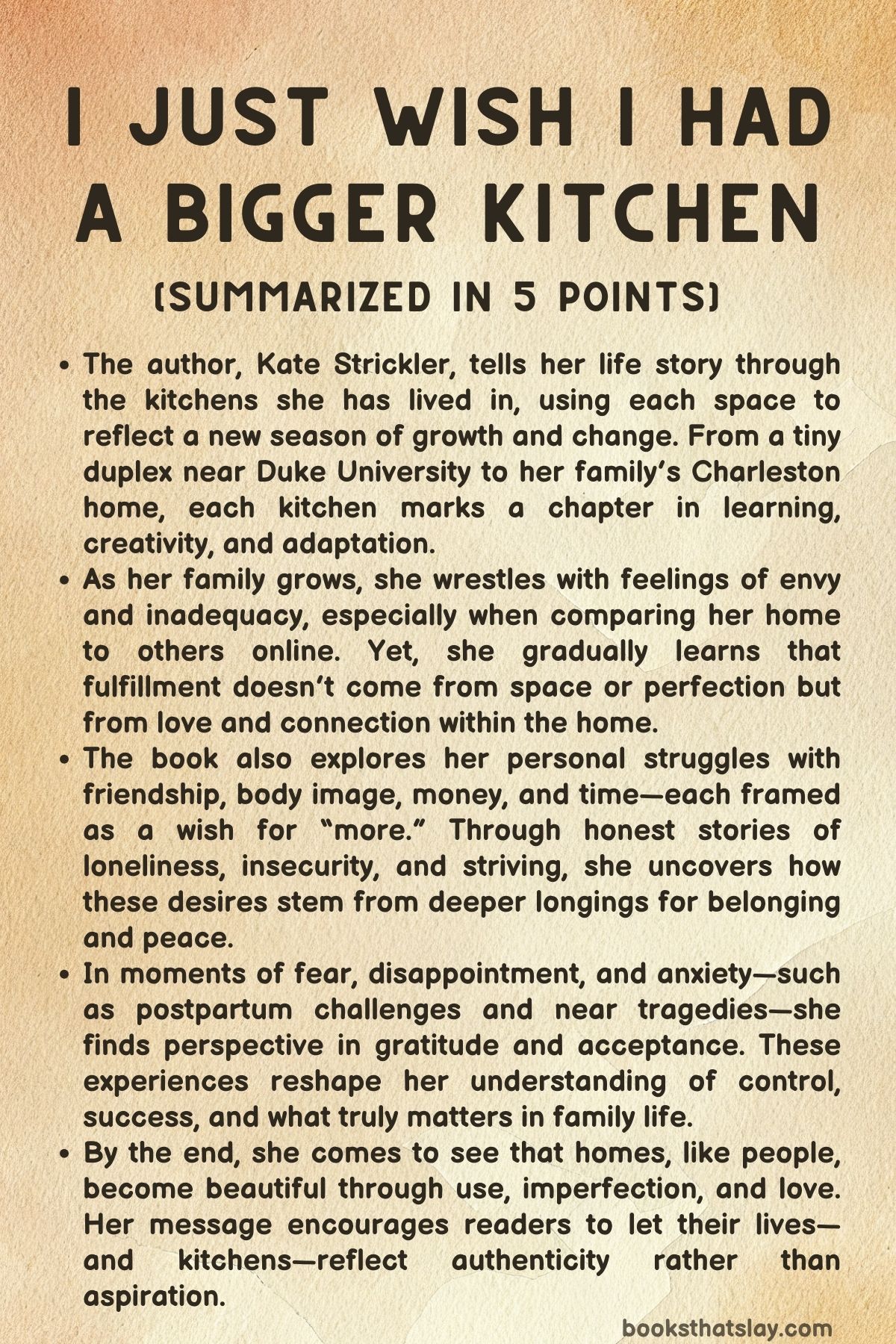

I Just Wish I Had a Bigger Kitchen by Kate Strickler is a memoir that explores the intersections of home, family, and identity through the evolving spaces the author has lived in. Known for her relatable storytelling and humor, Strickler reflects on how her life—marriage, motherhood, work, and self-discovery—has been shaped by the kitchens and homes she has inhabited.

From cramped duplexes to more comfortable houses, she uses each setting as a lens to examine broader themes of contentment, comparison, and purpose. The book blends personal anecdotes with practical reflections, revealing how imperfection, gratitude, and love make a house truly feel like home.

Summary

The story begins with Kate Strickler recalling the early years of her marriage to Nate, set in a modest duplex near Duke University in Durham, North Carolina. The space was tiny, greasy, and old, yet it became the backdrop of her first experiences with cooking, homemaking, and motherhood.

As Nate pursued his law degree, she taught herself to cook, photographed her meals, and found pride in her small, robin’s-egg-blue kitchen. When developers bought the property, the couple moved, reluctantly closing that first chapter of shared domestic life.

Their next home, still in Durham, felt luxurious by comparison—a three-bedroom rental with hardwood floors and a fenced yard. Here, Strickler embraced motherhood fully, savoring afternoons with her toddler on the porch while waiting for Nate to return from school.

Life was defined by simple rhythms and quiet joy. When Nate graduated, the couple relocated to Charleston, South Carolina, where they bought their first home in West Ashley.

The kitchen—with granite counters and white cabinets—seemed like a dream realized. For six years, it became the heart of their growing family.

As more children arrived, the dream kitchen began to feel small. Strickler jokes that her cooking tools overflowed into every corner of the house.

She yearned for more space, yet a quote on her wall about “little houses” reminded her that love mattered more than size. Still, envy crept in, worsened by social media.

The endless stream of perfect homes made her question her own. Unlike television shows that once showcased celebrity mansions, social media blurred the lines between the attainable and the ideal, making comparison feel personal and constant.

She began to reflect on how space, comfort, and satisfaction are deeply relative. What feels cramped in one context might feel generous in another.

Her reflections evolve into a larger meditation on contentment, exploring how financial trade-offs, anxiety, and cultural pressure shape the way people think about their homes. The longing for a bigger kitchen, she realizes, often represents a desire for control, validation, or peace rather than space itself.

A turning point comes when she visits a woman named Meg from her church. Expecting a large, pristine house, she instead finds a small, cluttered home overflowing with warmth.

Meg’s lively kitchen is filled with family, conversation, and the smell of a fresh salad. This visit changes Strickler’s perspective: she begins to see beauty in imperfection and hospitality in simplicity.

Inspired, she allows her children to decorate their rooms freely and views mess as a sign of life rather than failure. Memories of her aunt’s and parents’ homes reinforce the lesson that love, laughter, and adaptability matter more than cleanliness or coordination.

From these experiences, Strickler develops a new philosophy: a home’s worth lies in how well it serves its people. She starts reorganizing her house not for aesthetics but for function—asking whether each space “works” for her family.

As she personalizes rooms and accepts their lived-in look, affection replaces frustration. When friends visit with their children, chaos takes over—crumbs, toys, noise—but the joy of shared company transforms her perspective.

The clutter becomes evidence of life being fully lived.

Her insight crystallizes when her home is professionally staged for photos. The cleaned, minimalist version looks stunning yet hollow.

Once the photos are done and real life resumes—with toys, dishes, and fingerprints—the house regains its warmth. She understands that perfection often erases personality.

The wear and tear of family life—the scratches, spills, and stains—are not flaws but proof of belonging.

As the book progresses, Strickler expands her reflections beyond the kitchen, examining broader themes of friendship, body image, money, and time. Each represents another “space” she has tried to enlarge or perfect.

In her search for deeper friendship, she recalls the loneliness of early adulthood and the struggle to form genuine bonds as a new mother. She learns that meaningful connection grows not from having more friends but from investing in a few real ones.

When she turns to body image, she traces insecurities back to adolescence and the pressure to look a certain way. Her perspective shifts during a summer without mirrors, when she discovers relief in not constantly evaluating herself.

Over time, she learns to see her body as a record of her life—marked by pregnancies, change, and growth. Through her husband’s example of steady, sustainable health habits, she redefines wellness as peace rather than perfection.

Money brings another lesson. Growing up in Charleston’s wealthy circles, she once equated possessions with worth.

Early marriage and tight finances taught her the joy of simplicity, but rising income later reignited comparison. She recognizes that financial peace requires redefining “enough” and resisting the temptation to constantly move the goalpost.

Gratitude and generosity, she concludes, create far more happiness than accumulation.

Time, too, becomes a central theme. Strickler, known for her efficiency, realizes that constant productivity can hollow out life.

The pandemic’s enforced slowness helps her rediscover joy in unhurried days. Later, when both she and Nate leave traditional work structures to prioritize family, she learns that freedom is not found in having more hours, but in how one chooses to fill them.

The smallest moments—baking, talking, resting—become the truest measure of a life well spent.

Interwoven through these reflections is the shadow of fear. After losing her uncle in a car accident before college, she develops a persistent anxiety about tragedy.

Parenthood amplifies it—worrying over her husband’s safety, her children’s wellbeing, and life’s unpredictability. A near-drowning, a car accident, and travel anxiety expose how fragile her sense of control really is.

Gradually, she learns to live despite uncertainty, to let her children take risks, and to trust that love, not fear, should guide her choices.

She also confronts disappointment—both small and large. From postpartum struggles to failed vacations and sleepless nights with her youngest child, she comes to understand that disappointment is an inevitable part of life.

Yet these moments, too, carry lessons in empathy, humility, and perspective.

By the end, Strickler reflects on photos from her family’s earlier homes—shabby furniture, imperfect walls, and messy counters. What endures are not the aesthetics but the people, laughter, and ordinary moments.

Writing the book helps her see that building a good life comes from consistency in small things—daily acts of love, care, and attention. She likens this to becoming “Real,” borrowing the metaphor from The Velveteen Rabbit—a life shaped by use, marked by experience, and deepened by time.

Through every kitchen and every chapter, Kate Strickler finds that the real wish was never for a bigger kitchen, but for peace with what she already has. The beauty of home, she concludes, lies not in its perfection but in the life it holds.

Key People

Kate Strickler

Kate Strickler, the author and narrator of I Just Wish I Had a Bigger Kitchen, emerges as a deeply reflective, honest, and evolving protagonist whose journey intertwines domestic life, self-perception, and spiritual growth. Through her narrative voice, she bridges the ordinary and the profound—examining kitchens, friendships, and daily routines as mirrors of her inner transformation.

Early in life, Kate embodies a perfectionist tendency, yearning for control and validation through beauty, order, and achievement. The small, imperfect kitchens of her early marriages become metaphors for her struggle with contentment; each new space triggers both gratitude and comparison.

Her evolving relationship with physical spaces parallels her emotional maturation—moving from envy and self-doubt toward acceptance and peace.

Kate’s reflections extend beyond domesticity into deeper existential terrains—friendship, body image, wealth, and time. Her tone balances humility and insight; she does not present herself as enlightened but as a learner continually reshaping her understanding of what matters.

The reader witnesses her gradual liberation from comparison culture, her shift from external validation to intrinsic joy, and her embrace of imperfection as beauty. As a wife, mother, and creator, Kate personifies resilience—admitting fears of loss, failure, and inadequacy but choosing to keep living fully despite them.

Her defining growth lies in realizing that fulfillment is not about having more—space, friends, money, or time—but about using what she has with gratitude and love.

Nate Strickler

Nate, Kate’s husband, is portrayed as a calm, pragmatic counterpart to her introspective and emotional nature. From the early days of their marriage, his steady ambition—studying law while Kate explores homemaking—anchors their shared life.

Nate’s character represents quiet dependability and partnership rooted in mutual respect rather than flamboyant romance. His disciplined, long-term approach to goals contrasts with Kate’s impulsive striving, teaching her the value of patience and sustainable growth.

As the years progress, Nate’s choices reveal an understated courage—especially when he leaves his law career to support Kate’s growing business and family-centered priorities. His transformation from conventional provider to co-partner in domestic and creative work underscores a redefinition of masculinity within modern family life.

Nate embodies balance: he is both disciplined and adaptable, a realist who also values emotional well-being. His presence in the narrative reinforces one of the book’s central truths—that home and partnership thrive not through perfection but through shared purpose and evolving support.

John Robert, Scout, Millie, and Alberta

Kate and Nate’s four children—John Robert, Scout, Millie, and Alberta—represent the living heart of the family and the tangible reminders of life’s changing seasons. Each child, though not explored in great psychological depth individually, contributes to the evolution of Kate’s worldview.

John Robert, the eldest, symbolizes early parenthood’s mixture of exhaustion and wonder; his presence during the couple’s modest years in Durham mirrors their learning curve as both parents and adults. Scout becomes a mirror for Kate’s anxieties about social acceptance and self-image, especially when facing exclusion at school or the pressures of “cool clubs.

” Through Scout, Kate confronts her inherited insecurities and learns to model healthier self-acceptance.

Millie and Alberta, born later, arrive as embodiments of both joy and humility. Millie’s near-drowning and Alberta’s difficult infancy force Kate to face vulnerability head-on—learning compassion, patience, and the fragility of control.

Alberta’s sleeplessness and Kate’s postpartum anxiety push the narrator beyond pride into dependency and gratitude for her community. Collectively, the children humanize the narrative, grounding abstract reflections in the chaos and tenderness of daily family life.

They remind Kate—and the reader—that perfection is not the goal of parenting or home-making; presence is.

Meg

Meg, the woman from Kate’s church whose tiny, cluttered kitchen radiates warmth and abundance, serves as a pivotal symbolic figure in the narrative. She represents an alternative vision of success—one rooted in generosity and authenticity rather than appearances.

Kate’s visit to Meg’s home becomes an awakening: the realization that a space’s worth lies not in its size or cleanliness but in its capacity to nourish and welcome. Meg’s ability to create beauty and hospitality in imperfection inspires Kate to embrace her own home’s mess as a mark of life and love.

Meg thus functions as both a mentor figure and a moral compass, embodying the grace that comes from contentment and wholehearted living.

Aunt Ellen

Aunt Ellen stands as another influence shaping Kate’s understanding of home and identity. Through Ellen’s joyful and adaptable spirit, Kate observes a model of hospitality unbound by perfection.

Ellen’s home, like Meg’s, is described not for its aesthetic appeal but for the comfort it exudes. She represents an older generation’s wisdom—living proof that a house evolves with the people in it.

Her presence affirms that love, laughter, and adaptability are the real cornerstones of domestic life. For Kate, Aunt Ellen’s example reinforces that the essence of home is not found in structure but in spirit.

Anna

Anna, Kate’s sister, mirrors her in both closeness and contrast. Their shared experiences of motherhood—marked by struggle, disappointment, and recovery—deepen Kate’s empathy and dissolve her earlier judgments.

Anna’s difficult births, juxtaposed with Kate’s postpartum challenges, reveal the universal vulnerability of motherhood. Through Anna, Kate learns that comparison—even among sisters—is futile and that compassion begins with recognizing one’s shared fragility.

Anna’s presence grounds the narrative in family continuity, underscoring how sisterhood, like friendship, is forged through honesty and mutual grace rather than ease.

The Friends

Kate’s friends, though numerous and unnamed in some cases, collectively represent the evolution of adult connection in an age of digital comparison and busyness. They embody the ebb and flow of community—showing up in small, transformative acts like driving her children or sitting beside her in postpartum darkness.

These friendships mark Kate’s gradual learning that intimacy grows not from social breadth but from consistent, vulnerable presence. The women who surround her reflect the shifting ecosystem of modern motherhood, where isolation often coexists with virtual connectedness.

Through them, Kate discovers that belonging is not something found—it is something built, day by day, through shared lives.

Analysis of Themes

Home and Identity

The connection between home and identity forms the emotional core of I Just Wish I Had a Bigger Kitchen. Through her experiences in various houses, the author reveals how physical spaces reflect personal evolution.

Each kitchen she inhabits becomes a marker of growth—from her first humble duplex where she learned to cook and mother, to the larger homes that mirrored changing ambitions and family dynamics. What begins as a yearning for more space evolves into a reflection on how environments shape, and are shaped by, one’s inner life.

The author comes to understand that the home’s true beauty lies not in its aesthetic appeal but in its ability to serve the people who live there. The clutter, scratches, and crowded countertops become emblems of a life that is active and authentic rather than curated for display.

By contrasting the staged perfection of social media homes with the warmth of lived-in spaces, she recognizes that identity is rooted in use, memory, and belonging—not appearance. Ultimately, her acceptance of imperfection parallels her acceptance of herself, linking the evolution of her home to her maturation as a woman, wife, and mother.

Comparison and Contentment

The tension between envy and gratitude runs throughout the narrative, revealing how modern life fuels discontent through endless comparison. The author’s longing for a larger kitchen becomes a metaphor for the universal desire for “more”—more beauty, wealth, approval, and time.

She acknowledges that social media has blurred the boundary between aspiration and reality, making others’ abundance feel both near and unattainable. This awareness does not immediately erase her envy but helps her examine its roots in insecurity and cultural pressure.

By recalling her encounter with Meg’s small, cluttered but joy-filled home, she realizes that satisfaction does not depend on square footage but on the quality of life lived within it. Over time, she reframes her perspective from lack to sufficiency, learning that gratitude must be practiced intentionally.

The law of “diminishing returns” she later applies to money also applies to lifestyle: the pursuit of more rarely leads to happiness. Instead, contentment grows when she stops comparing and defines what “enough” means for her own family.

Friendship and Belonging

The exploration of friendship reveals the author’s deeper search for community and acceptance. Her struggles to form lasting connections—first in college, later as a young mother—expose the vulnerability of adult relationships.

The loneliness of starting over, the awkwardness of initiating contact, and the insecurity of not being “enough” all shape her understanding of belonging. Through the steady kindness of friends who step in during her postpartum crisis, she learns that love often requires both humility and dependence.

The act of receiving help becomes as transformative as giving it. Her reflections on social inclusion, from childhood cliques to adult “mom groups,” underscore how the need for connection persists across life stages.

By the end, she embraces the idea that belonging is not about being universally liked or having numerous friends but about cultivating depth and presence with a few trusted people. Genuine friendship, like a home, must be functional, forgiving, and capable of holding life’s messiness without judgment.

Body Image and Self-Acceptance

The theme of body image in I Just Wish I Had a Bigger Kitchen extends beyond physical appearance to questions of self-worth and peace. The author’s memories of teenage comparisons, diet obsession, and mirror fixation reveal how societal ideals distort personal perception.

Her eventual decision to limit mirrors in her home becomes symbolic of choosing inner calm over external validation. She learns to view her body not as an ornament to be perfected but as a living record of her experiences—childbirth, aging, and effort.

Her husband’s steady approach to health and her reflections on aging actresses demonstrate that dignity and confidence can coexist with imperfection. Through her evolution, the author rejects the pursuit of an unattainable ideal and replaces it with gratitude for functionality, strength, and resilience.

The acceptance of her changing body mirrors her acceptance of a cluttered home: both are imperfect spaces that hold the richness of real life.

Money and Simplicity

The author’s reflections on money highlight the moral and emotional weight that financial choices carry. Her upbringing in an affluent community instills early associations between wealth and worth, but adult life challenges those assumptions.

Marriage introduces contrasting attitudes toward spending and saving, and the years of financial restraint during her husband’s law school become an education in simplicity and joy. She realizes that contentment does not increase with income; instead, expectations expand to fill every new level of comfort.

Social media amplifies this cycle, offering endless comparisons that make satisfaction elusive. Over time, she learns that the healthiest financial mindset is rooted in sufficiency and gratitude rather than acquisition.

Her “goalpost” metaphor captures the danger of allowing others’ lifestyles to define success. In redefining wealth as the ability to live according to personal values—time with family, generosity, peace—she aligns financial simplicity with spiritual clarity.

Time and Presence

The scarcity of time emerges as both a modern anxiety and a philosophical question. The author’s drive for productivity once gives her a sense of control but eventually becomes a trap that erodes joy.

Her reflections during the pandemic mark a turning point, as enforced stillness reveals the richness of unhurried moments. She comes to see that busyness masquerades as purpose but often conceals avoidance—the fear of stillness and reflection.

Her shift toward mindful living, embodied in the small act of baking a pie, symbolizes the rediscovery of presence. The decision for her husband to leave his job for a slower family rhythm demonstrates that time, like money, must be spent with intention.

By learning to protect margin—the breathing room in life—she finds that peace lies not in managing every minute but in accepting time’s limits. Presence, not productivity, becomes her measure of a well-lived day.

Fear, Control, and Acceptance

Underlying the narrative is a deep examination of fear—the fear of loss, tragedy, and failure to protect those she loves. Early experiences with death and near misses instill a chronic vigilance that shapes her worldview.

Yet as she matures, she begins to recognize control as an illusion. Her gradual exposure to flying after years of anxiety becomes a metaphor for choosing courage over certainty.

Through faith, reflection, and repeated experience, she learns to live alongside risk rather than trying to eliminate it. This acceptance also influences her parenting: she allows her children to face small dangers, understanding that safety cannot come at the cost of growth.

The theme culminates in her recognition that life’s beauty lies in its fragility. The “reps” of everyday tasks—driving, cooking, tucking children into bed—become acts of trust in a world that cannot be controlled but can still be cherished.

Imperfection and Realness

The concluding chapters of I Just Wish I Had a Bigger Kitchen return to a central revelation: that a meaningful life is built through imperfection. Whether in her home, friendships, or self-image, the author comes to see mess and wear as signs of authenticity rather than failure.

The metaphor of The Velveteen Rabbit’s “becoming Real” captures this beautifully—love and time make us imperfect, but they also make us genuine. The polished, empty house prepared for photography represents an appealing but lifeless ideal; true beauty, she realizes, exists in the fingerprints and laughter that fill the rooms afterward.

Her journey transforms the pursuit of “better” into the practice of gratitude for what already is. In embracing imperfection, she discovers the quiet grace of ordinary life—the way small acts of care, repetition, and faith accumulate into a home, a body, and a soul that feel real.