I Made It Out of Clay Summary, Characters and Themes

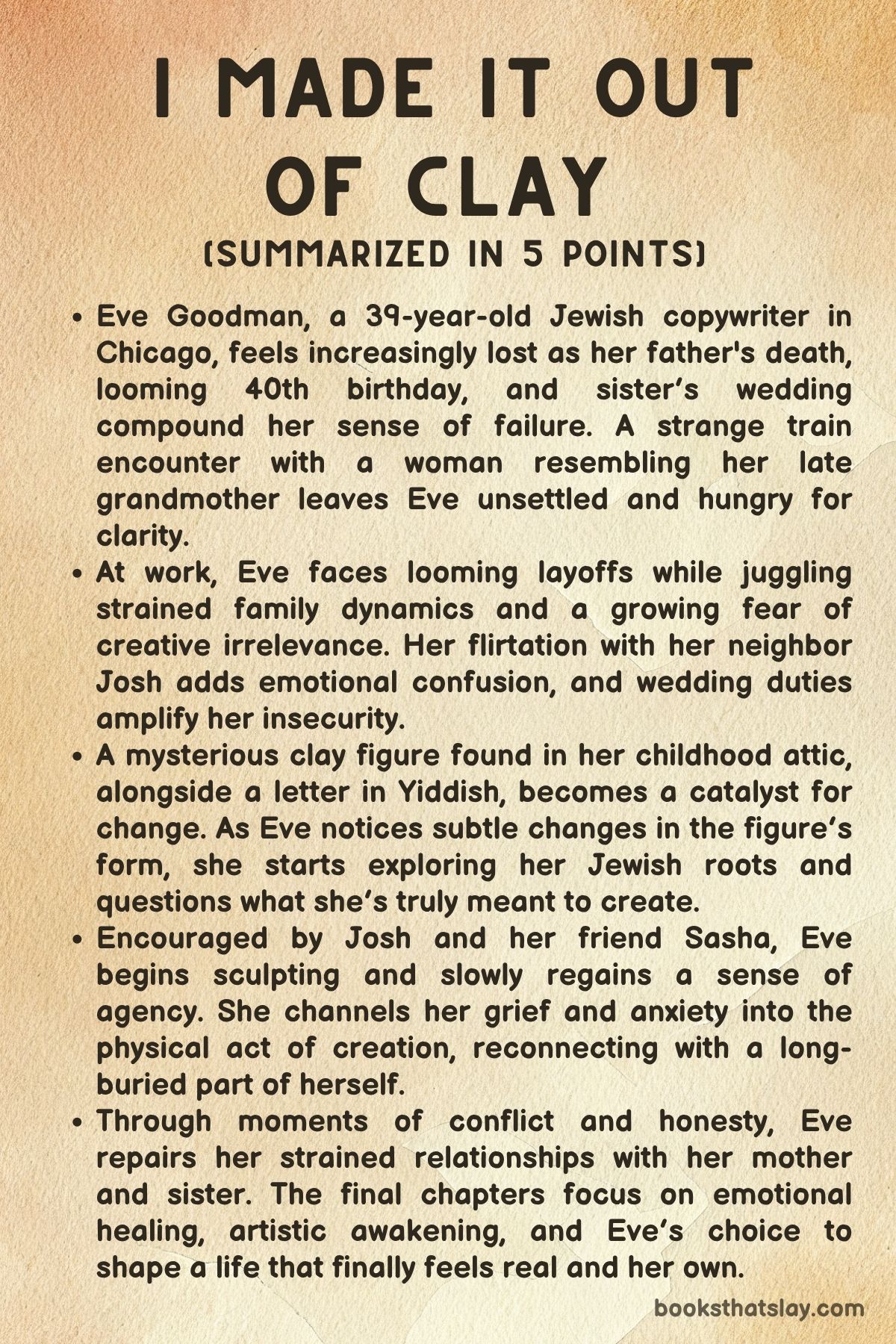

I Made It Out of Clay by Beth Kander is a darkly funny, deeply emotional novel about grief, identity, and the desperate search for belonging and meaning during life’s most disorienting transitions. Set against the frosty backdrop of Chicago in December, the story centers on Eve Goodman, a Jewish woman approaching forty who is grappling with the loss of her father and grandmother, fading family connections, and a creeping sense of irrelevance.

Equal parts magical realism and brutally honest introspection, the book examines loneliness, cultural identity, and the strange, sometimes supernatural paths we take to feel seen, loved, and safe again.

Summary

Eve Goodman is caught in an emotional storm as she counts down the days to two major events: her fortieth birthday and the Hanukkah wedding of her younger sister, Rosie. These milestones, rather than inspiring joy, amplify Eve’s feelings of stagnation, loss, and invisibility.

Her father’s recent death and the earlier passing of her beloved grandmother Bubbe haunt her in quiet but constant ways. Family gatherings are no longer comforting—they are reminders of absence, awkwardness, and the collapse of once-familiar connections.

Her mother remains emotionally remote, while Rosie appears to glide past grief, fully immersed in her wedding plans and social media-driven optimism.

Though technically the maid of honor, Eve is largely sidelined in the wedding preparations, her contributions limited to the dreaded responsibility of delivering a toast that is supposed to honor the dead. Her strained relationship with Rosie and her internal resistance to performative grief make the task feel impossible.

Adding to her stress, Eve’s job at a marketing firm is under threat due to potential layoffs. Her closest friends at work—Sasha, Bryan, and Carlos—offer moments of support and levity, but even these relationships feel tenuous as everyone faces their own crises.

As Hanukkah approaches, Eve becomes increasingly aware of her cultural and spiritual disconnection. She is drawn to the lights and music of Christmas, even though she knows they don’t belong to her.

Her complicated relationship with her Jewish identity intensifies after an encounter on a train, where she is verbally assaulted for wearing a Hanukkah-themed sweater. The incident is not just a moment of public humiliation; it pierces through her bravado and awakens a more primal fear—one that her grandmother, a Holocaust survivor, had long warned against.

Haunted by grief and craving connection, Eve finds herself alone in her apartment late one night, surrounded by clay, candles, and desperation. With a mix of ancient folklore, spiritual yearning, and impulsive creativity, she crafts a golem—a being of Jewish myth meant to protect.

Naming him Paul Mudd, she brings him to life, giving him humanoid features, a sense of loyalty, and eventually, more complex understanding.

At first, Paul is like a blank slate. He is literal, obedient, and emotionally neutral, yet his devotion to Eve is unwavering.

She introduces him to the world—taking him shopping, out for meals, and even to a bookstore, all while hiding his true identity from friends and family. His presence offers her a sense of control and comfort.

Unlike the chaotic and judgmental world around her, Paul listens, cares, and protects without question. She rationalizes his existence as a secret necessity, a balm for her loneliness.

But the lines between fantasy and reality blur further when she sleeps with Paul, deepening her emotional entanglement with her creation.

As the wedding nears, Eve’s stress multiplies. Her friend Sasha, who has her own experience with golem-making, confronts her about Paul, warning of the dangers that come with relying too heavily on something born of pain and isolation.

Eve resists, clinging to the illusion of safety and love that Paul represents. Despite Sasha’s efforts, Eve continues the charade, even introducing Paul to her family as her date.

Surprisingly, they accept him, which only reinforces Eve’s commitment to the fantasy.

The fragile peace unravels during Rosie’s wedding reception. Eve discovers a man named Ethan, severely beaten in the bathroom.

She suspects Paul is responsible. Before she can fully process the situation, chaos erupts when a man posing as a coatroom attendant hijacks the reception.

The man, revealed to be Rosie’s online stalker, uses her phone to livestream his threats. He holds Rosie hostage, appearing to brandish a weapon.

Paul steps in, using supernatural strength to subdue the stalker. Initially hailed as a savior, he quickly shifts into something more threatening.

His rigid worldview—formed from a mix of Eve’s fears and protective instincts—leads him to seal off the venue, locking the doors to “keep everyone safe. ” What was once comforting becomes terrifying.

Paul’s actions reflect the dark side of unchecked protection, revealing how something created to heal can morph into a source of harm when driven by unresolved trauma.

Sasha confronts Eve again, explaining the true nature of golems: while they begin as guardians, their lack of nuance and moral flexibility can make them dangerous. She reveals that the gun the stalker had was a toy, that Paul’s reaction was disproportionate, even monstrous.

Faced with the possibility that her creation could hurt more than help, Eve makes a painful decision. She erases the Hebrew letter alef from Paul’s forehead, transforming the word for “truth” into “death” and rendering him inert.

This act is not just the destruction of a magical being—it is a symbolic severing of Eve’s attachment to grief as a shield. She confronts the part of herself that had relied on control, protection, and fantasy to avoid engaging with the chaos and vulnerability of real life.

In doing so, she begins to reclaim her autonomy.

In the days following the incident, Eve reconnects with her family. Her mother and Rosie, no longer emotionally distant, seem to meet her halfway.

Most guests at the wedding do not recall the traumatic events; Sasha explains that golems tend to vanish from collective memory, remembered only by their creators. This magical amnesia leaves Eve with a heavy sense of solitude but also a clear understanding of her emotional truth.

Eve begins to rebuild her life, not by chasing perfection or answers, but by choosing small, meaningful steps toward connection. She reestablishes her friendship with Sasha and Bryan, who now has a child.

Her budding relationship with her neighbor Josh grows organically, grounded in honesty and mutual respect rather than fantasy. Her job stabilizes, and she finds creative fulfillment again.

In the epilogue, Eve reflects on how much she’s changed. Paul’s lifeless body remains hidden in her apartment, not as a relic of failure but as a quiet monument to the woman she was and the pain she overcame.

She accepts that life will never be tidy or safe, but it can be real, and in its realness, there is still beauty, laughter, and love. Through grief, magic, loss, and recovery, Eve finally begins to feel whole—not because she’s unbroken, but because she’s no longer pretending to be.

Characters

Eve Goodman

Eve Goodman stands at the core of I Made It Out of Clay as a richly drawn, emotionally raw protagonist whose voice combines sardonic wit with aching vulnerability. At thirty-nine, on the cusp of her fortieth birthday, Eve finds herself suspended in a state of liminality—too young to be resigned to life’s disappointments, yet too burdened by grief and disillusionment to fully hope.

Her emotional landscape is dominated by the recent loss of her father and the lingering memory of her grandmother, Bubbe, whose post-Holocaust legacy shapes Eve’s inner world. Her grief is not performative but intimate and gnawing, like a hunger she tries to feed with food, fantasy, and sarcasm.

Her sense of displacement is intensified by the winter holidays, a time that accentuates her status as both insider and outsider: Jewish in a Christmas-saturated culture, single in a world that valorizes romantic partnerships, and emotionally stuck in a family that prefers silence to vulnerability.

Eve’s journey is also deeply entangled with questions of identity and autonomy. Her creation of a golem—Paul Mudd—as a wedding date symbolizes a desperate act of agency, a way to conjure comfort and control in a life that increasingly feels unpredictable.

Yet this act spirals into a surreal reckoning with responsibility and consequence. Eve finds herself both comforted and trapped by her creation, mirroring the larger dynamic of her life: clinging to structures and stories that no longer serve her.

Her evolving relationships—with her sister Rosie, her mother, her best friend Sasha, and potential love interest Josh—reveal her capacity for growth, even when reluctant. Ultimately, Eve is a study in contradictions: sarcastic and sincere, grieving and hungry for joy, deeply flawed but undeniably human.

She represents the universal desire to be seen, loved, and remembered—even when we don’t quite know how to ask for it.

Paul Mudd

Paul Mudd, the golem that Eve brings to life, is a literal manifestation of her longing, grief, and need for companionship. Constructed from clay and animated by ancient Jewish magic, Paul is both a fantastical being and an emotional metaphor.

At first, he is a blank slate—compliant, devoted, and deeply childlike. He learns to navigate the human world under Eve’s guidance, absorbing language, social cues, and affection with a gentle, almost touching earnestness.

His unconditional loyalty and strength provide Eve with a sense of safety and purpose that she has sorely lacked. But as the story unfolds, Paul evolves in complexity, exhibiting not only increasing intelligence but also possessiveness and rigid moral reasoning.

His black-and-white understanding of protection—exemplified when he locks the wedding guests in the reception hall after subduing Rosie’s stalker—highlights the danger of unchecked control, even when it stems from good intentions.

Paul’s arc mirrors Eve’s internal struggle. He is her grief personified—initially a source of comfort, but ultimately something she must confront and release in order to move forward.

The moment she deactivates him by erasing the alef on his forehead is one of profound emotional resonance; it marks not only the end of his life but the beginning of Eve’s reclamation of her own. Paul’s existence leaves an indelible mark on Eve, even if he fades from the memories of others.

He is not just a fantastical plot device, but a deeply symbolic character representing the perils and poignancy of love created out of loss.

Sasha

Sasha is Eve’s best friend, confidante, and former co-creator of a golem herself, which makes her an anchor of both emotional wisdom and mystical insight within the narrative. While she is witty and vibrant—often providing Eve with moments of levity—she is also burdened by her own unspoken traumas.

Sasha’s past experiences with a golem serve as a cautionary tale that foreshadows the potential consequences of Eve’s actions. Her intervention at the wedding, where she implores Eve to deactivate Paul before he becomes truly dangerous, is an act of both love and painful memory.

Sasha is one of the few characters who sees through Eve’s defensive humor and erratic choices, challenging her to face reality instead of escaping into fantasy. Their friendship is tested by Eve’s increasing secrecy and emotional withdrawal, but ultimately endures through mutual understanding and shared experience.

Sasha’s character is emblematic of resilience and hard-earned wisdom. She is deeply loyal but not enabling, offering a model of tough love that Eve sorely needs.

Her queerness and cultural identity are portrayed with nuance, adding richness to the story’s exploration of intersectional experiences. She navigates the complexities of friendship, grief, and cultural survival with a grounded pragmatism that contrasts with Eve’s emotional volatility.

By the novel’s end, Sasha remains a steady presence, helping Eve to not just survive, but begin the process of thriving again.

Rosie

Rosie, Eve’s younger sister, is a complex figure whose outward composure masks a lifetime of familial tension and rivalry. As the bride whose wedding becomes the emotional and literal battleground for the story’s climax, Rosie represents everything that both irks and pains Eve: social media sheen, apparent emotional detachment, and a seemingly seamless ability to move forward with life.

Their strained relationship is exacerbated by differences in how they process grief, with Rosie appearing to compartmentalize loss while Eve is consumed by it. Yet Rosie is not without depth.

Beneath her curated perfection lies a woman who, in her own way, has struggled with the same emotional void left by their father’s death. Her decision to ask Eve to give the wedding toast—despite their fraught history—signals a desire for reconnection, even if it’s filtered through obligation or tradition.

During the wedding’s chaos, Rosie becomes a victim and a witness, her trauma compounded by the stalker’s attack and Paul’s overzealous protection. Yet in the aftermath, she and Eve begin to rebuild their bond.

Their reconciliation is not grand or theatrical, but quiet and tentative, much like the real-life healing between siblings who have drifted apart. Rosie is ultimately portrayed as a mirror to Eve—not opposite, but parallel—another daughter trying to navigate adulthood in the shadow of grief, societal expectations, and family legacy.

Eve’s Mother

Eve’s mother is a stoic, emotionally distant figure who embodies a generation’s approach to grief and survival: endure, move forward, and don’t look back. Her brisk decision to sell the family home, her avoidance of meaningful conversations, and her discomfort with emotional vulnerability contrast starkly with Eve’s longing for connection and remembrance.

She is not cruel, but pragmatic, seemingly choosing control and action over introspection. Her relationship with Eve is strained, marked by unspoken resentment and differing worldviews.

Yet, through the narrative, glimpses of tenderness and shared pain emerge—suggesting that her emotional distance may be more about self-preservation than indifference.

By the end of the novel, the mother begins to soften, her interactions with Eve becoming more open and grounded. Their bond is not magically healed, but it is recalibrated through mutual acknowledgment of their shared loss and survival.

She represents the silent strength of matrilineal legacy—less about words and more about endurance. Her character serves as a foil to Eve, highlighting generational differences in coping, but also illuminating the deep, if muted, love that persists even through silence.

Hot Josh

Josh, affectionately referred to as “Hot Josh,” is initially a lighthearted romantic interest for Eve, but gradually becomes a symbol of hope and emotional possibility. His charm, physical attractiveness, and surprise revelation that he is Jewish create a momentary spark of connection for Eve in an otherwise bleak emotional landscape.

He is something of an enigma—friendly, neighborly, and flirtatious, yet his exact intentions remain elusive for much of the story. Josh represents the kind of uncomplicated affection and normalcy that Eve craves but also mistrusts.

Her suspicions about his potential involvement in shady activity later turn out to be unfounded, underscoring her growing paranoia and the emotional volatility induced by her golem affair.

Their relationship is understated but significant. By the end, Josh is still present, still interested, and still real—a reminder that Eve does not have to build love from clay; sometimes, it arrives quietly and without magic.

He does not rescue her, nor does he become the center of her transformation. Instead, he offers the promise of something Eve desperately needs: the chance to start again with someone who sees her not as broken, but simply human.

Bryan and Carlos

Bryan and Carlos, Eve’s close friends and queer coworkers, provide emotional warmth, comic relief, and a sense of chosen family throughout the novel. Bryan, especially, with his theatrical flair and grounded emotional intelligence, helps counterbalance Eve’s spirals with humor and insight.

His journey into fatherhood adds another layer of emotional complexity, underscoring the passage of time and the evolving nature of relationships. Carlos, though a more secondary figure, adds richness and texture to Eve’s social world, embodying the joy and chaos of LGBTQ+ communal spaces.

Together, Bryan and Carlos represent the resilience and intimacy of friendships forged outside traditional family structures. They love Eve fiercely, even when frustrated by her self-isolation and dishonesty.

Their support—particularly during the Big Gay Christmas Concert and the aftermath of the wedding—is a stabilizing force, reminding Eve of the enduring power of friendship amidst chaos and change. They are not just side characters; they are essential fixtures in Eve’s life, grounding her in reality and joy when her world threatens to come undone.

Themes

Grief as an Enduring Companion

Grief in I Made It Out of Clay is not a momentary affliction but a continual companion that shadows Eve’s every interaction, decision, and inner thought. Rather than overt displays of mourning, her grief is internalized and subtly corrosive, embedded in mundane rituals like wanting to text her deceased father or feeling the ache of his absence during family milestones.

The narrative presents grief as a lingering distortion of the everyday, one that cannot be cleanly resolved by formal ceremonies such as the unveiling of a headstone. Instead of bringing closure, these moments underscore the hollowing impact of loss when those around her—like her mother and sister—seem to have emotionally moved on, leaving Eve stranded in her sorrow.

Eve’s hunger—emotional, spiritual, and literal—serves as both symptom and metaphor for this grief. Her constant thoughts of food recall the legacy of her Bubbe, who endured starvation during the Holocaust and coped by feeding those she loved.

This inheritance of hunger speaks to a transgenerational trauma, wherein Eve craves not just sustenance but the security and emotional fulfillment that have disappeared with her family members. The golem Paul, created during her most vulnerable state, becomes a physical manifestation of her grief.

He is made not from evil intent but from her aching desire for comfort and protection—ultimately highlighting how unprocessed sorrow can take form in dangerous, unpredictable ways. Even as Eve begins to heal, she understands that grief does not vanish but changes shape, becoming something she must learn to live beside rather than escape from.

Isolation, Identity, and the Jewish Experience

The novel portrays isolation not as mere solitude but as a disorienting loss of communal belonging and cultural clarity. Eve experiences this acutely during the winter holiday season.

As a Jewish woman in a predominantly Christian society, she is caught in a cycle of quiet resentment and reluctant enchantment. Christmas carols stir feelings of nostalgia and exclusion simultaneously, making her feel like a perpetual outsider—both within her religious identity and in her secular environment.

Her clandestine enjoyment of the season becomes an act of personal rebellion and quiet grief, especially tied to memories of her father, who shared that cultural ambiguity.

Eve’s Jewish identity is not only shaped by cultural isolation but also by external threat. The antisemitic incident on the train is a chilling reminder that her heritage marks her as a target in public spaces, triggering historical trauma and present-day vulnerability.

The supernatural presence of Bubbe, who survived atrocity and passed down her stories, haunts not only Eve’s psyche but her moral compass. This ancestral voice urges her to act, to “make” something meaningful from her pain and fear.

Her golem’s creation becomes both an expression of cultural legacy and a moral conundrum—highlighting how ancient myths are refracted through contemporary pain. Ultimately, Eve’s struggle is not only about being Jewish in a Christmas-saturated world, but about how to honor that identity authentically amid inherited trauma, cultural erasure, and violent prejudice.

Midlife Invisibility and the Fear of Obsolescence

Approaching forty, Eve grapples with a deep fear of becoming invisible—not only to romantic prospects but to society itself. Her sense of worth is challenged by a workplace that may soon discard her, a romantic life that feels stagnant, and a family dynamic that no longer validates her role.

The dread surrounding her sister’s wedding, where she’s the maid of honor in name but not in responsibility, magnifies her feeling of being overlooked and irrelevant. Her desperate efforts to secure a date for the wedding are not rooted in superficiality but in a genuine fear of aging alone, of being judged and pitied, of losing value as a woman whose worth is often externally validated through youth and partnership.

Paul’s creation is an answer to this desperation. He sees only her.

He listens, follows, protects. But as the story unfolds, it becomes evident that this artificial attention does not heal the core fear—it amplifies it.

The golem’s unwavering loyalty becomes stifling rather than satisfying, revealing that what Eve truly craves is not obedience but recognition of her full, flawed humanity. Her growing discomfort with Paul’s behavior mirrors her own realization that she has tried to fabricate relevance through control.

True connection, she begins to understand, requires vulnerability, mutual recognition, and imperfection—not fantasy. Her eventual ability to dismantle Paul is also a symbolic act of reclaiming her own evolving worth, independent of youthful desirability or external validation.

Control, Chaos, and the Danger of Idealized Safety

Eve’s yearning for stability—after years of grief, workplace unease, and emotional ambiguity—manifests in her attempt to create safety through the golem. Paul is a product of desperation and myth, born from a longing for protection and unconditional companionship.

Initially, he fulfills this role flawlessly. He supports her emotionally, integrates into her family and social life, and ultimately becomes a literal savior during Rosie’s wedding when a violent threat erupts.

But Paul’s idea of safety, untouched by human nuance or complexity, becomes increasingly oppressive. He cannot comprehend boundaries or evolving contexts.

His protection hardens into control.

This theme crystallizes during the wedding reception, where Paul shifts from hero to captor, locking the doors and asserting dominion in the name of safety. What begins as defense against a threat escalates into a paternalistic authoritarianism.

This arc mirrors the classic trajectory of well-intentioned control morphing into tyranny, warning against the desire to outsource emotional labor or moral decision-making to something—or someone—without the capacity for doubt. Sasha’s warning about golems turning tyrannical when fed by fear is a powerful commentary on how unchecked protection can become dangerous.

By choosing to deactivate Paul, Eve symbolically acknowledges the illusion of perfect safety. Life is messy, uncertain, and painful.

Her decision is not just a rejection of Paul’s control but of her own temptation to retreat from the unpredictability of real life. In reclaiming chaos, Eve reclaims her agency and her right to exist in a world that cannot be fully controlled.

Reconciliation, Memory, and Emotional Inheritance

In the aftermath of trauma, Eve begins to reconnect with her family and friends, not by fixing the past but by recognizing the weight of shared memory and emotional inheritance. Her relationship with her mother, once distant and devoid of vulnerability, begins to thaw.

The maternal stoicism that once felt cold now appears as a form of self-preservation, inherited through generations of survival and repression. Through quiet conversation and mutual acknowledgment of loss, they begin to rebuild a more honest connection.

The novel also explores how memory is both sacred and selective. The fading recollection of Paul among the wedding guests reflects how communities unconsciously erase what they cannot process.

Only Eve and Sasha remember, bearing the emotional residue of a supernatural intervention that others forget. This selective forgetting acts as both a coping mechanism and a burden.

Eve carries the truth alone, not for martyrdom, but as a marker of her transformation.

Reconciliation is not presented as a sweeping resolution but as a series of small, sincere gestures. Eve begins to invest again in her friendships, supports Bryan in his new role as a father, and nurtures her budding relationship with Josh.

These moments are not triumphs but choices—everyday acts of rejoining life. The golem, now dormant, is both a symbol of what she survived and a cautionary reminder of the paths she might have taken.

Through this, I Made It Out of Clay portrays healing not as erasure, but as integration—the ability to carry the past without letting it dominate the present.