I Think We’ve Been Here Before Summary, Characters and Themes

I Think We’ve Been Here Before by Suzy Krause is a character-driven exploration of love, grief, memory, and impending doom, set against the backdrop of an uncanny cosmic threat. Told through the eyes of multiple characters scattered across Canada and Berlin, the novel blurs the lines between déjà vu and destiny, humor and sorrow, apocalypse and routine.

Through these contrasting lenses, Krause dissects how people respond to personal loss and global crisis, and how our emotional patterns may repeat just like the cosmic ones we dread. The story balances wit and melancholy while examining how deeply ordinary moments become profound when time might be running out.

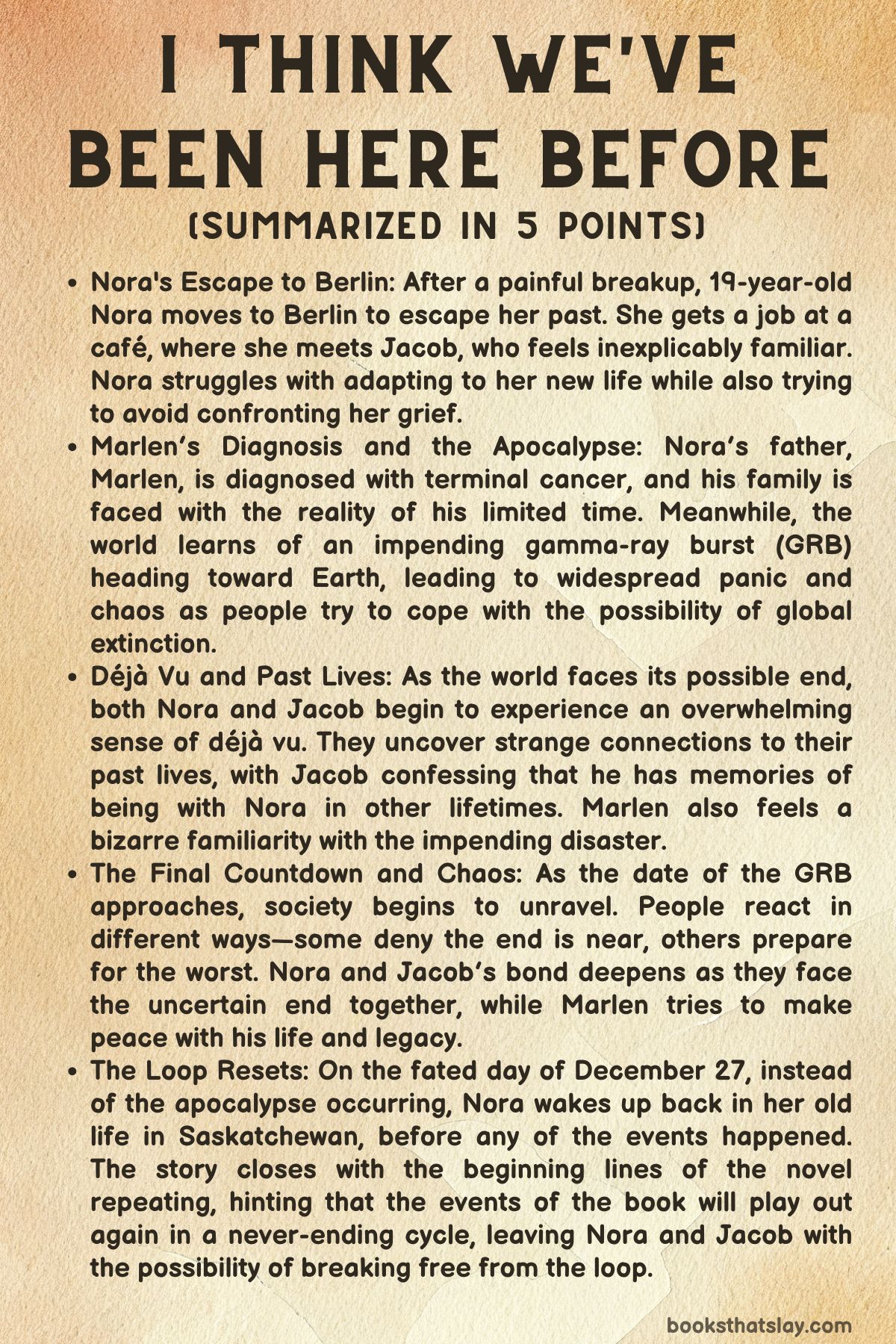

Summary

The story begins with Nora, a young Canadian woman reeling from her first heartbreak, which she likens to a stubborn bedbug infestation—ever-present and impossible to exterminate. Seeking escape and transformation, she leaves her life behind to move to Berlin through a work-abroad program.

There, she begins working at a café named Begonia and rents a flat with new roommates. One of them is Jacob, a man she’s never met but feels inexplicably familiar with.

Their interactions are tinged with a strange emotional déjà vu, a sense that their lives are echoing something from before, although neither can pinpoint what.

Meanwhile, back in rural Saskatchewan, Nora’s family is gathering for Thanksgiving. The reunion is emotionally charged.

Her mother, Hilda, reveals that Nora’s father, Marlen, has been diagnosed with terminal cancer. The announcement is messy and stirs discomfort, especially in the absence of Nora, whose physical distance now feels like an emotional chasm.

Marlen, a trivia enthusiast and amateur researcher, attempts to soothe the situation with information and humor, much to Hilda’s frustration. Their dynamic reflects a lifetime of mismatched emotional coping strategies, now made more urgent by looming loss.

The family’s personal grief is suddenly dwarfed by a larger, existential threat. A double gamma ray burst—an astronomical event that could lead to mass extinction—is reported by scientists across the globe.

Initial projections warn of catastrophic atmospheric and ecological damage. The news sparks panic, disbelief, and introspection.

For Marlen, the event is strangely familiar. He has spent the past year writing a book about such a phenomenon without telling anyone.

Now, he wonders if his creativity was foresight. His cancer, too, had been something he sensed long before doctors confirmed it.

His reflections move from the rational to the metaphysical.

Nora is initially shielded from the global panic in Berlin. Her café begins to empty out as customers react to the news, and it is Jacob who tells her the world may be ending.

Nora finally turns her phone on and becomes engulfed by the storm of digital alarm. Her roommate Sonja joins her in processing the strange stillness that has fallen over the city.

Nora experiences a spiraling hysteria—not of fear, but from the unreality of it all. Her feelings for Jacob deepen as they spend more time together, their bond a fragile but genuine comfort amid chaos.

As the world inches closer to potential catastrophe, the narrative shifts across characters. In Canada, Irene, Hank, and their son Ole contend with their own fragmented responses.

Ole’s internal journey becomes marked by dread and philosophical inquiry, comparing death to staring into a starless Grand Canyon. His mother Irene clings to letters that suggest the gamma ray burst might be a hoax, while Hank dismisses them as harmful denial.

Their arguments become a mirror to many couples facing collapse—an unraveling of shared reality.

Nora, trapped in Berlin, attempts to return home but can’t find a flight. Her interaction with her logical and detached roommate Petra further isolates her emotionally.

In a moment of spontaneous rebellion, she gets a tattoo, a gesture meant to reclaim a piece of agency in a collapsing world. Jacob and Nora grow closer, their made-up roles as Mr.

and Mrs. Schmidt now taking on sincere meaning.

They walk through an eerie Berlin, stealing candy, making holiday crafts, and clinging to their growing love as the skies darken with more than just metaphor.

Back in Canada, other lives continue unfolding. Iver, an older man who has never bought anything online, suddenly becomes obsessed with ordering gifts for everyone he knows.

The end of the world has given him urgency to express unspent affection. He even reaches out to Elsie, someone he never liked, in order to acquire arcade machines for others.

Their awkward conversation ends in a small but significant reconciliation. His son Ole, once emotionally distant, helps decorate a Christmas tree with Iver.

Silence between them becomes a form of mutual understanding.

Irene and Hank begin repairing their relationship, brought together by shared memories and honest confrontation. Hank admits to his past failings, and Irene accepts the apology with grace.

In Germany, Jacob and Nora’s pretend relationship takes on the contours of something real. Their crafted rituals and spontaneous adventures evolve into a source of comfort and emotional truth.

They find joy in handmade decorations, paper snowflakes, and quiet acts of rebellion.

Marlen and Hilda respond to the encroaching end by listening to radio broadcasts and preparing for the worst. They create a mural dedicated to Nora, an act of preservation and love.

Despite Marlen’s worsening illness, the couple finds solace in each other’s presence and shared history. The world outside may be falling apart, but their home becomes a sanctuary of memory and care.

As time grows short, Nora finally makes it back to Canada. Her airport farewell with Jacob is emotionally loaded, but he surprises her by returning moments later, unwilling to let her go.

They fly back together, landing in a countryside that is eerily calm, in contrast to the urban chaos they’ve left behind. The townspeople, instead of succumbing to fear, continue with quiet rituals—garage sales, goodbyes, gift-giving.

Life, though fraying, is still lived with meaning.

The family gathers at Hilda and Marlen’s home for what could be their final Christmas. Irene hangs decorations in the basement, turning it into a warm haven.

Friends and relatives arrive, sharing stories, laughter, and meals. Even Alfie, the ever-giving outsider, is finally welcomed with open arms.

As they sit together, surrounded by lights and handmade snowflakes, Marlen shares his final thoughts on death and time. He suggests that life might not end, but instead loop infinitely, giving us a chance to relive, remember, and revise endlessly.

The gamma ray burst finally arrives. But there is no screaming, no chaos—only calm.

The family holds hands, trading stories, watching the approaching light as a symbol not of obliteration, but of transformation. In their final moments, they are united not by fear, but by memory, love, and the choice to face the unknown together.

The ending doesn’t offer answers, but it does offer peace—a quiet recognition that even at the end of all things, the essence of being human remains unchanged.

Characters

Nora

Nora is the emotional anchor of I Think We’ve Been Here Before, and her journey encapsulates the human impulse to flee pain only to find it reinvented elsewhere. Devastated by her first heartbreak, Nora equates emotional devastation to a parasitic infestation—bedbugs that can’t quite be eradicated, no matter how much she scrubs her life clean.

Her flight to Berlin represents not just a change of scenery but a full existential reset, embracing the unfamiliar as a means of outpacing memory. However, her newfound solitude becomes fertile ground for introspection rather than escape.

Her job at the café Begonia is both symbolic and literal—a place of temporary beauty, blooming in unfamiliar soil, but fragile nonetheless. Nora’s connection with Jacob, tinged with uncanny familiarity, introduces the theme of timeless connection and possible past lives or parallel memories, aligning well with the novel’s motifs of déjà vu and cyclical existence.

Even as the apocalypse looms, her emotional chaos—being suspended between departure and return, between loss and new affection—mirrors the outer world’s disintegration. Nora’s eventual return home and reunion with her family underscores her arc from flight to acceptance, from individual heartbreak to shared mortality, culminating in a quiet surrender to love and memory over fear.

Jacob

Jacob is introduced as a mysterious yet comforting presence in Nora’s Berlin chapter, his character interwoven with feelings of familiarity and past intimacy that defy logical explanation. His own fragility, exposed in a moment of panic and vulnerability, balances his earlier allure.

Jacob is not simply a love interest but a mirror for Nora’s own emotional state—wounded, searching, and caught in the interstices of memory and desire. The fake marriage they concoct evolves into a tender, absurd, and increasingly meaningful bond, one born from survival instincts but sustained by emotional authenticity.

His character is marked by a quiet depth, someone who grapples with fear not through detachment but through connection, offering a kind of poetic defiance against the unraveling of the world. When he reappears at the airport in a moment of near-melodramatic romance, it is not contrived but charged with emotional sincerity.

His final gesture of joining Nora on the journey home speaks to his desire for meaningful continuity, even in the face of cosmic finality.

Hilda

Hilda, Nora’s mother, is defined by her emotional complexity and maternal instincts, which vacillate between frustration, fear, and fierce love. Her initial reaction to Marlen’s cancer diagnosis and Nora’s absence is a tangled web of disappointment and longing.

She yearns for connection, for the opportunity to mother actively, but is denied by both her husband’s emotional withdrawal and her daughter’s physical absence. As the story progresses, Hilda becomes the emotional spine of the family, channeling her anxiety into tangible actions—preparing for Christmas, creating a mural, organizing and remembering.

These acts of creation in the face of destruction reflect her deep need to preserve love and memory, not as resistance to death, but as tribute to life. Her emotional arc—from suppressed grief to open vulnerability—aligns with the novel’s central themes of emotional honesty and enduring love, even when words and actions falter.

Marlen

Marlen, Nora’s father, is an intellectual romantic whose stoic, often awkward, manner of dealing with crisis masks a profound inner world. His initial use of humor to deflect from the gravity of his terminal cancer diagnosis contrasts with his later introspective turn, particularly through the mysterious book he’s written, predicting not only his death but the apocalypse itself.

Marlen straddles the line between eccentric scholar and prophetic figure, embodying the novel’s preoccupation with the unknowable and the cyclical. He is deeply loving but emotionally reserved, retreating into research and trivia when real emotion threatens to overwhelm him.

His book, his silence, and his ultimate willingness to sit beside his family as the gamma ray burst arrives all reflect a man who has come to peace with the invisible forces he once sought to measure. Marlen’s reflections on invisibility versus ignorable threats elevate him from a mere supporting character to a philosophical compass for the narrative.

Irene

Irene, mother to Ole and estranged from him for much of the novel, is one of the most emotionally transparent characters. Her anxieties—whether stemming from imagined cougar attacks in her youth or the very real specter of planetary death—expose her vulnerability.

She clings to gestures of normalcy, to rituals, and to the comfort of denial when reality becomes too overwhelming. Her love for her family is raw, often spilling over in tense interactions with Hank or bittersweet memories of Ole.

Irene’s dreams and moments of déjà vu imbue her character with a sense of metaphysical sensitivity. She is a mother striving to find meaning through repetition, through baking, decorating, and remembering.

Her creation of the sanctuary-like basement for the final Christmas becomes an act of sacred preservation, a mother’s final embrace of a world she cannot save but can still love.

Hank

Hank is Irene’s husband and Ole’s father, a man whose emotional repression masks a simmering grief. His stoicism is challenged by the apocalypse, as the structures he once relied upon—rationality, distance, emotional quietude—begin to crumble.

His clashes with Irene expose the fractures in their marriage, but also demonstrate the possibility of renewal through honesty. When he finally opens up, it is not with grand declarations but with quiet admissions, apologies, and the willingness to endure discomfort.

Hank’s arc is less visible but equally profound—a man learning to be vulnerable not in heroic fashion, but through small, consistent gestures of presence and forgiveness.

Ole

Ole is the embodiment of youthful alienation and emotional paralysis. Haunted by guilt, uncertainty, and the silence between him and his family, Ole is a deeply interior character whose journey is marked by avoidance.

Living with his estranged father Iver, he exists in emotional limbo, unable to confront or articulate his grief. Yet the apocalypse jolts him into engagement, not through words but through shared actions—decorating a tree, returning home, accepting embraces.

Ole’s transformation is subtle but resonant; he moves from passivity to participation, from ghosting his past to reclaiming it. In him, the novel explores the complexity of male emotional development and the quiet bravery of choosing connection when it would be easier to retreat.

Iver

Iver, Ole’s grandfather, offers a redemptive portrayal of aging as a time not of resignation but of spontaneous generosity. Motivated by regret and impending extinction, Iver channels his unresolved emotions into a flurry of gift-giving, trying to leave behind fragments of joy.

His awkward but touching phone call to Elsie reveals a man unaccustomed to emotional transparency, yet willing to stumble into it. Iver’s dynamic with Ole, built largely on shared silence, represents a non-verbal form of love, where acts replace words and presence becomes affirmation.

His character reminds us that even in the eleventh hour, growth, connection, and kindness are still possible.

Alfie

Alfie is a quiet but powerful presence, a symbol of community and continuity. Through her tireless work at the Pot Hole coffee shop and her quiet perseverance, she embodies the spirit of everyday heroism.

In a world unraveling, Alfie’s steadiness becomes an anchor. Her eventual inclusion into the family’s final Christmas gathering is more than a gesture of kindness—it is an acknowledgment of her place in the web of shared humanity.

She represents those who give without being asked, who serve without expectation, and who deserve recognition not just for their labor, but for their love.

Themes

Disorientation and Displacement

Nora’s relocation from Canada to Berlin after a painful breakup encapsulates a broader feeling of existential disorientation that permeates I Think We’ve Been Here Before. The city is foreign in every sense—language, culture, weather, and emotional temperature—mirroring the internal alienation she feels.

Her decision to sever ties with everything familiar is not just an escape from a failed relationship, but an act of self-erasure and reinvention. The sense of being untethered manifests physically and psychologically, from awkward exchanges in a second language to the eeriness of uncanny recognition in Jacob.

The sensation of having been somewhere—or with someone—before is repeated throughout, blurring the lines between memory, imagination, and reality. Displacement, then, becomes both a literal and metaphorical condition.

While Nora tries to outpace her grief, the shifting political and environmental backdrop ensures that no place offers true refuge. As the threat of a gamma ray burst emerges, the idea of ‘home’ itself becomes meaningless.

Borders dissolve under shared catastrophe, and personal histories seem arbitrary against impending annihilation. Yet, paradoxically, this global disorientation triggers a desperate grasp for the grounding elements of identity: family, love, belonging.

The unfamiliar becomes familiar when layered with emotion, and in a strange city on the brink of collapse, Nora begins to construct a fragile sense of connection that rivals what she lost back home. Her movement across geographies is not a journey of linear healing, but one of layered confusion, fragmented memory, and tentative reorientation.

Mortality and the Smallness of Human Control

The cancer diagnosis of Marlen sets the stage for a contemplation of mortality that later magnifies with the news of the gamma ray burst. What begins as a private, family-centered confrontation with death morphs into a collective reckoning with extinction.

This escalation from the intimate to the planetary underscores the illusion of human control. Marlen tries to understand his illness by researching and cataloging facts, a habit of using intellect to make sense of the body’s betrayal.

But when the world itself faces destruction, his framework collapses. The existential weight of cosmic randomness—how something as remote and abstract as a gamma ray burst can undo life—renders science impotent in offering comfort.

Hilda’s emotional disarray, Irene’s flashbacks, and Nora’s physical withdrawal reflect the destabilizing effect of confronting mortality in its rawest, most unmanageable form. Attempts at preparation—stockpiling food, writing books, constructing bunkers—are shown to be symbolic gestures rather than solutions.

Death becomes not just inevitable but unknowable in form and timing. The futility of trying to outsmart it forces the characters to abandon strategy for presence.

The emphasis shifts from surviving to experiencing: laughing, baking, forgiving, and remembering. The story insists that if death is a certainty and control an illusion, then meaning must be found not in conquest over death but in the surrender to life’s fleeting, beautiful moments.

Memory, Repetition, and the Loop of Existence

One of the most haunting ideas in the book is the notion that time might not be linear, but cyclical. Through repeated motifs—Nora’s déjà vu with Jacob, Irene’s dream mirroring her waking life, Marlen’s eerily predictive manuscript—the story toys with the idea that we may be living variations of the same life over and over.

Memory becomes less a record of the past and more a whisper of other versions of ourselves. The gamma ray burst, in this context, is not simply an end but a possible restart.

Marlen’s final philosophical proposition, that death may usher in a loop of reliving life, gives poetic coherence to the title I Think We’ve Been Here Before. The eerie familiarity of events, the recurrence of certain emotions, and the revisiting of unresolved tensions all suggest that the characters are caught in some karmic cycle—reliving, revising, forgetting, and remembering again.

This perception imbues their final acts with added poignancy. Each goodbye becomes a rehearsal for another, each joy a memory waiting to be reawakened.

The repetition isn’t merely structural—it’s emotional. The characters are constantly returning to core truths about love, regret, identity, and desire.

If time is circular, then so is healing: never complete, always underway. The book suggests that rather than fearing the end, we might consider the possibility that we are always at the beginning of another loop.

Human Connection as Resistance to Annihilation

Throughout the story, characters resist the pull of despair not through grand heroics but through the deliberate act of staying close to one another. Whether it’s setting up a Christmas tree, making paper snowflakes, calling an old enemy to ask for help, or holding someone’s hand in a corner store, these acts of love and togetherness form a quiet rebellion against the end.

The constructed marriage between Nora and Jacob, first born out of loneliness, becomes something real not through romantic climax, but through shared silliness, confession, and care. Iver, driven by a lifetime of emotional suppression, spends his final days buying gifts, reconnecting with people, and resurrecting lost relationships.

These gestures—tiny in the scope of cosmic destruction—carry enormous emotional weight. The story affirms that meaning is not imposed from above but built in the spaces between people.

Even as systems collapse and logic fails, the characters remain steadfast in their attempts to preserve love. They create rituals not because they believe they will change the outcome, but because the act of creating gives shape to chaos.

The apocalypse, then, is not met with explosions or violence, but with a community of people wrapping presents, baking buns, and telling stories. These connections—messy, flawed, heartfelt—are presented as the most authentic response to oblivion.

Rather than being defined by their approaching end, the characters are remembered for their attempts to live fully in the shadow of it.

The Invisibility of Catastrophe

One of the most unsettling features of the gamma ray burst is its invisibility. Unlike an earthquake or a fire, it provides no immediate sensory warning—no sight, no smell, no sound.

This makes it an ideal metaphor for the kind of psychological and emotional crises that people endure silently: depression, heartbreak, regret, and terminal illness. Marlen, in reflecting on his manuscript, notes that the real danger is not that the event is “ignorable” but that it is invisible.

This reframing deepens the emotional resonance of the narrative. Many of the characters, even before the official apocalyptic news, are already battling private forms of collapse.

Nora’s heartbreak, Irene’s childhood trauma, Ole’s shame and withdrawal, Iver’s unspoken regrets—these are invisible catastrophes, ignored by those around them, but no less devastating. The gamma ray burst simply externalizes what has already been happening internally.

This convergence of visible and invisible crisis blurs the line between what counts as disaster. It also raises questions about attention: what we choose to notice, when we decide to act, and how we determine which threats are real.

In making the apocalypse quiet and slow, the novel encourages a more empathetic engagement with the hidden struggles people carry daily. The world may end not with a bang, but with a sigh, a moment of remembrance, or a touch.

The silence of destruction forces a louder kind of emotional honesty—one where people finally say what they mean and ask for what they need.