Imposter Syndrome Summary, Characters and Themes | Joseph Knox

Imposter Syndrome by Joseph Knox is a psychological thriller that blurs the lines between truth and illusion, identity and performance. Centered on a nameless con artist who stumbles into the dangerous remnants of a wealthy family’s unresolved trauma, the novel explores themes of manipulation, control, grief, and the fragile nature of reality.

Knox crafts a world in which every character is either deceiving or being deceived, where grief is weaponized and power is hidden behind charm and wealth. The protagonist’s journey through layers of impersonation and conspiracy reveals not just the darkness in others, but also the moral disintegration within himself. It’s a story about what it means to inhabit someone else’s skin, and how far one can go before becoming the very lie they’ve told.

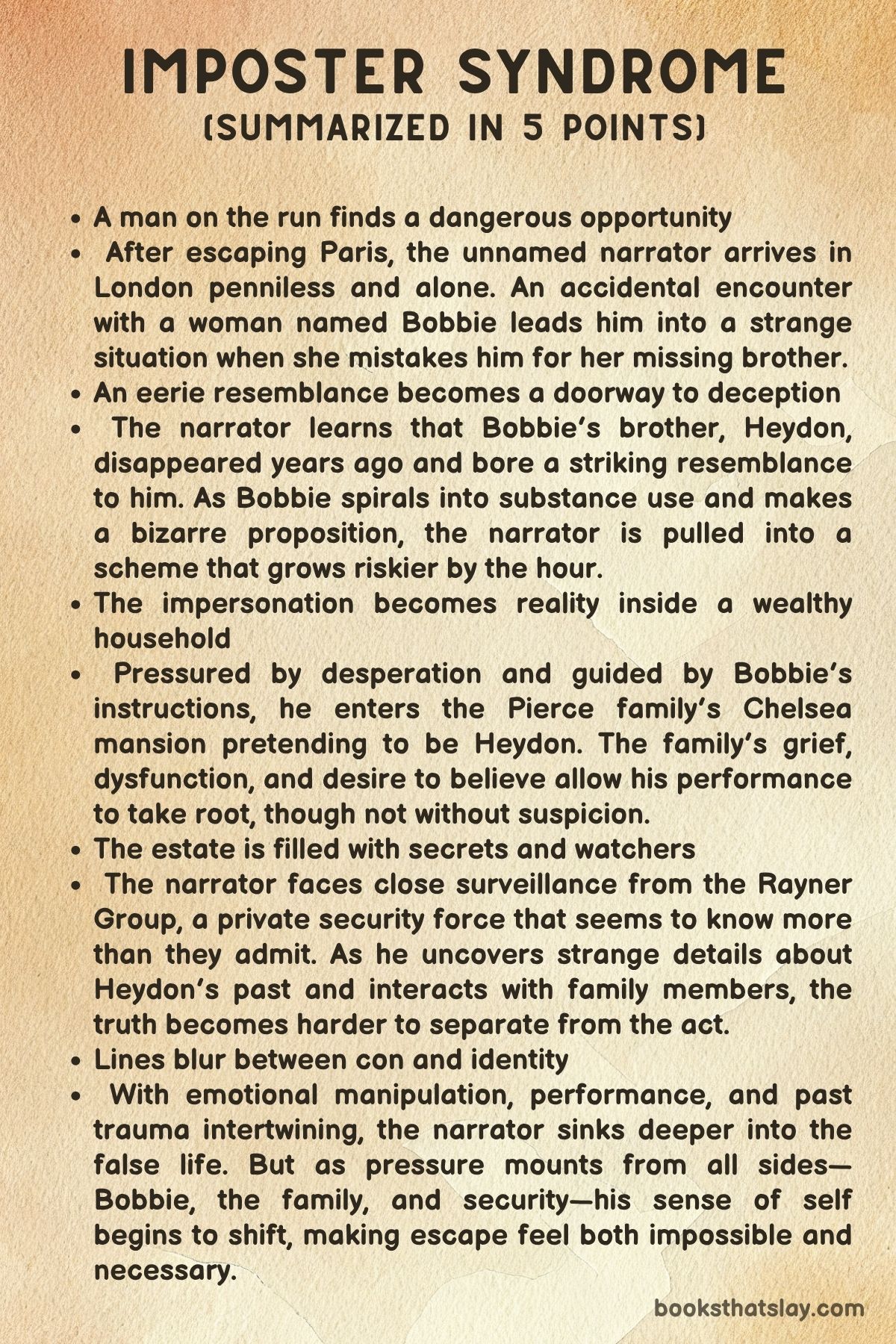

Summary

A nameless drifter arrives in London after fleeing a shadowy incident involving a woman named Clare in Paris. Struggling with exhaustion and guilt, he survives by petty theft and cunning.

At Heathrow Airport, he encounters Bobbie Pierce, a chaotic young woman convinced he is her long-lost brother Heydon. He plays along initially, accepting her hospitality and listening to her fraught stories of family dysfunction.

Their night together ends with her tattooing a broken heart beneath his eye, believing it symbolizes her missing brother. The next day, she disappears, leaving him with the unsettling suggestion that he break into her wealthy family’s Chelsea mansion.

Driven by desperation, he does exactly that. Caught inside by the family’s private security, his tattoo convinces them he might truly be Heydon.

Bobbie’s mother, Miranda, and older sister, Reagan, don’t entirely believe him, but they don’t reject him either. Instead, Miranda makes a strange proposition: she wants him to continue impersonating Heydon in order to retrieve sensitive items from a criminal named Badwan.

In exchange, she offers £25,000. The narrator agrees, stepping into a new role with high stakes and a thin margin for error.

To perfect the illusion, Reagan oversees his grooming and reconstructive surgery. The narrator, now dubbed “Mr.Lynch,” is immersed in Heydon’s former life and begins to uncover cracks in the Pierce family’s façade. He observes Heydon’s emotional decline through old photographs and hears about a traumatic family event: the drowning of the youngest sibling, Theo, under Heydon’s watch.

The guilt from that tragedy haunted Heydon for years, leading to addiction and paranoia. As Lynch digs deeper, the lines between impersonation and reality begin to blur.

He questions whether Heydon truly committed suicide or was destroyed by forces far beyond his control.

Lynch successfully retrieves the case from Badwan, barely making it before a deadline. When opened, it contains a phone encased in cement and a Faraday cage.

The phone holds a disturbing pre-recorded message from Heydon, detailing his psychological torment. He speaks of being manipulated by his mother, hallucinations involving his dead brother, and being stalked by magpies—symbols of his crumbling mind.

The phone also reveals messages to a contact named “CTRL,” suggesting he was monitored or attacked just before his death.

Reagan and Miranda are shaken. Forensic analysts uncover a vanished media file and signs of digital erasure.

Lynch becomes convinced Heydon was targeted, not mentally ill. He presses forward, determined to expose whoever orchestrated the breakdown.

His search leads him to Dr. Kate Matten, Heydon’s therapist.

Matten, threatened into compliance by a man named Alan Peck, admits she broke confidentiality under coercion. Her story confirms Lynch’s theory: Heydon’s mind was deliberately warped through a campaign of gaslighting, impersonation, and surveillance.

A man named Vincent Control was even paid to impersonate Theo, but he ends up murdered, his death staged as suicide.

As Lynch’s obsession grows, he discovers links between the conspiracy and Hartson Holdings, a powerful and corrupt conglomerate with a logo matching his tattoo. This suggests Lynch, like Heydon, is now part of something larger—marked and manipulated.

He confronts Reagan again, who admits she always knew he wasn’t Heydon but allowed the deception because of her need for answers. Their emotional exchange is cut short when Reagan is summoned to a mysterious agency.

Lynch follows and meets Sebastien, a PR fixer who controls narratives for the powerful. Sebastien reveals how easily public perception can be bent and offers Lynch a chilling demonstration of burying scandal.

Still searching for truth, Lynch is evicted from his hotel and left vulnerable. He confronts Ronnie Pierce, Miranda’s estranged husband, who reveals more disturbing behavior: a grotesque shrine to dead women, revealing Ronnie’s own unraveling mind.

With each discovery, Lynch realizes how deeply the family is entangled in grief, manipulation, and denial.

Then comes the explosion. A Mercedes is blown up, killing four people.

Lynch, though not directly implicated, knows it’s connected. He’s approached by Elsa Carhart from the Rayner Group, who coldly informs him the job is done.

She gives him £50,000 and a warning to keep silent. Lynch visits the hospital where Miranda lies dying and confronts Reagan one last time.

She confesses she fought with Miranda before her fall down the stairs but insists it was accidental. Lynch is left to question every story he’s been told.

In a final twist, Lynch is abducted and taken to Matthew Hartson, a mogul who hired Sebastien to psychologically destroy Heydon as revenge against Miranda. But before Hartson can elaborate, a masked man—possibly Heydon—arrives and kills Hartson’s sons and security.

Lynch narrowly escapes, wounded and bewildered.

Seeking answers, Lynch finds Bobbie again at Heathrow. She reveals the truth: Heydon is dead.

The masked killer was Nate, her lover, who enacted revenge on the Hartsons. Bobbie admits to manipulating Lynch, using him as a decoy in their broader plan.

She offers a cold apology and promises to keep him safe if he takes the fall when necessary.

In the end, Lynch walks away, scarred and alone, but free from the madness. He finds a payphone, intending to call Clare—the only person who once knew his real self—holding on to the last hope of redemption.

The truth remains murky, but the performance, the lie, is finally over.

Characters

Lynch

Lynch, the protagonist of Imposter Syndrome, is an enigmatic and morally ambiguous character whose evolution forms the backbone of the novel. Initially introduced as a nameless grifter fleeing an undefined crime in Paris, Lynch exhibits a potent mix of cunning, desperation, and self-loathing.

His first interactions—petty thefts, manipulations, and moments of unexpected conscience—reveal a man perpetually in flux, vacillating between his conman instincts and a buried desire for redemption. Lynch’s transformation begins when he is pulled into the psychological and familial web of the Pierce family.

As he impersonates Heydon Pierce, Lynch undergoes a bizarre identity reformation. What starts as a performance turns into obsession, as he uncovers layers of Heydon’s trauma, manipulation, and potential murder.

His impersonation forces him to confront not just the external conspiracies but also his internal void—his lack of identity, moral compass, and past. By the novel’s end, Lynch is deeply changed.

Though still deceitful and elusive, he is more self-aware, driven not by greed but by a compulsion to uncover truth and seek justice for Heydon. His final act—walking away from the machinations of the rich and corrupt—signals a complex redemption arc, defined not by absolution but by hard-won autonomy.

Bobbie Pierce

Bobbie is the chaotic, wounded, and magnetic entry point into the Pierce family’s haunted narrative. Her first encounter with Lynch is marked by confusion and emotional volatility, mistaking him for her missing brother, Heydon.

This case of mistaken identity sets the novel’s central deception into motion, but Bobbie’s role is far from passive. Her vulnerability—evidenced by her addictions, her erratic behavior, and her desperate clinging to familial myths—is undercut by a calculating edge.

As the story progresses, Bobbie reveals herself to be a knowing player in the web of manipulation, ultimately confessing to using Lynch as a decoy in a larger scheme. Her motivations, however, are complicated.

She appears to be driven by grief, guilt, and a desire to protect her mother and memory of Heydon. In the end, her tearful conversation with Lynch reflects a mix of remorse and resolve, proving her to be both victim and architect of deception.

She embodies the novel’s titular theme—an imposter not in identity but in familial role, teetering between sister, conspirator, and puppet master.

Heydon Pierce

Though absent for much of Imposter Syndrome, Heydon casts a long and haunting shadow over every event. Through Lynch’s impersonation and investigation, Heydon emerges as a tragic figure—emotionally fractured, manipulated from childhood, and scapegoated by powerful interests.

He is introduced as a wayward son and possible suicide, but deeper layers reveal profound mental trauma rooted in the accidental death of his younger brother, Theo. This tragedy becomes the nexus of Heydon’s psychological unraveling, compounded by Miranda’s emotional manipulation and the subsequent exploitation by the Agency.

His descent into paranoia is not merely delusional—it is manufactured. The chilling video he leaves behind confirms he was targeted, gaslit, and stripped of his agency.

Heydon becomes a symbol of lost identity and the dehumanizing effects of institutional power. His posthumous voice is the most honest and heartbreaking in the novel, a scream for recognition that ultimately galvanizes Lynch’s transformation.

Miranda Pierce

Miranda is the icy matriarch of the Pierce family—at once powerful, distant, and emotionally unreachable. She orchestrates the central ruse of the novel: hiring Lynch to impersonate her dead son in order to recover sensitive belongings.

Her motivations, however, are rooted less in maternal love and more in control, reputation, and perhaps denial. She is portrayed as manipulative and emotionally cold, particularly in the video left by Heydon, which accuses her of psychological abuse and calculated detachment.

Her desire to maintain a sanitized family image leads her to embrace elaborate fictions, even if they erode the truth. In her final appearances, Miranda’s composed façade crumbles.

Her hospitalization, following a fall precipitated by an argument with Reagan, suggests the psychological toll of years of control and secrecy. She remains a potent figure, embodying the corrosive effects of guilt masked as strength and love expressed as domination.

Reagan Pierce

Reagan, the eldest Pierce daughter, is a fascinating study in repression and fractured identity. At first, she plays the role of the rational handler—coordinating Lynch’s transformation into Heydon, managing the family’s secrets, and maintaining public composure.

But as Lynch probes deeper, it becomes clear that Reagan is also deeply scarred. She knew Lynch was an imposter from the start, and yet allowed the masquerade to continue, perhaps out of curiosity, emotional exhaustion, or a subconscious desire to resurrect her brother.

Reagan is the novel’s most emotionally guarded character. Her complicated relationship with Miranda and Heydon is marked by unspoken guilt, particularly surrounding Theo’s death and Miranda’s subsequent emotional collapse.

Her final interactions with Lynch are steeped in fatigue and defeat. Though she helps resolve the financial arrangement and ensure his silence, her calm is brittle.

She embodies the cost of enforced decorum and the price of inherited trauma.

Mike Arnold

Mike Arnold, the bumbling security officer initially meant to watch Lynch, represents the ineffectiveness of institutional safeguards. He is easily manipulated, quickly dismissed from his post, and largely forgotten.

Yet his presence early in the novel underscores the chaos and desperation that surround the Pierce family’s inner workings. His removal is demanded by Lynch as a precondition for cooperation, revealing how fragile the family’s control really is.

Arnold serves as a reminder that appearances—uniforms, roles, authority—are easily pierced by those who understand the mechanics of manipulation.

Dr. Matten

Dr. Matten is Heydon’s former therapist and a crucial piece of the conspiracy puzzle.

Her initial wariness transforms into fear as Lynch confronts her with evidence of her compromised role. She confesses to being coerced into revealing confidential information, a victim of psychological terrorism involving her child’s safety.

Matten’s moral collapse is sympathetic—her maternal instinct is weaponized against her—but it also exemplifies the wider theme of institutional betrayal. Her reluctant honesty gives Lynch the next thread in the labyrinthine plot, and her arc underscores how even those trained to protect mental health can be crushed by larger systems of control.

Sebastien Keeler

Sebastien is the slick, chilling embodiment of corporate corruption and psychological manipulation. Operating as the face of “The Agency,” he reveals how crises are manufactured and truth is spun for elite clients.

He mentors Lynch in the art of silencing scandals, showcasing the tools of media control and narrative suppression. Keeler’s role in the harassment of Heydon is hinted at but never confessed, though it’s clear he orchestrated many of the illusions that destabilized him.

He operates without remorse, driven by efficiency and power. In the web of Imposter Syndrome, Sebastien is the spider—still, calculating, and utterly devoid of empathy.

Ronnie Pierce

Ronnie, the estranged father of the Pierce children, is portrayed as unhinged, grotesque, and deeply broken. His home is a grotesque museum of death, cluttered with memorabilia of famous deceased women, signaling his obsession with mortality and control.

He may have stolen Lynch’s passport, and his motives remain murky throughout. Ronnie’s madness is perhaps the most overt in the family, but it reflects the psychological rot infecting all of them.

He embodies the toxic legacy of unresolved grief and the patriarchal complicity in the systemic breakdown of the Pierce family.

Matthew Hartson and the Hartson Twins

Matthew Hartson and his sons represent the apex of the novel’s critique of power. Wealthy, surgically altered, and sociopathic, they are revealed to have funded Heydon’s psychological torture as revenge against Miranda.

Their role is emblematic of how the ultra-rich play games with human lives for sport and leverage. Their deaths at the hands of Nate (posing as Heydon) bring a grim form of justice, though not absolution.

Their story arc is a stark reminder of what happens when power becomes pathological.

Nate

Nate, Bobbie’s lover and the final impersonator of Heydon, is the hidden executioner in the novel’s climax. Cold, methodical, and deadly, Nate infiltrates the Hartsons’ fortress and carries out a meticulously planned revenge.

He is the ghost of Heydon given brutal form—a man who completes the arc of vengeance that Lynch was too fractured to finish. Though not deeply explored, Nate’s existence confirms Bobbie’s complicity and adds another layer to the novel’s theme of identity as performance.

His exit from the story is swift but unforgettable—a silent avatar of retribution.

Clare

Clare, the woman from Lynch’s past in Paris, serves as an emotional tether in an otherwise bleak narrative. Though largely absent, she represents the only flicker of genuine connection in Lynch’s life.

His final decision to call her signals his yearning for something real, beyond impersonation, manipulation, and survival. Clare is not a fully fleshed character, but her presence lingers as a symbol of redemption, or at least the hope of it.

Through this complex tapestry of characters, Imposter Syndrome constructs a world where truth is fluid, identity is weaponized, and everyone is playing a part—often unwillingly. Each character, regardless of screen time, contributes to the spiraling sense of dislocation and moral ambiguity that defines the novel’s chilling emotional core.

Themes

Identity and Impersonation

Imposter Syndrome explores identity not as a stable concept, but as something precarious, performative, and often manipulated. The protagonist enters the narrative as a nameless figure, already in flight from a misdeed, and very quickly assumes the identity of Heydon Pierce—a man whose life is riddled with trauma, mystery, and erasure.

What begins as a simple deception for survival soon spirals into a psychological abyss where the protagonist loses track of where the impersonation ends and his own persona begins. The facial tattoo, the grooming, and the conditioning are not just cosmetic; they symbolize a forced transformation that leads to internal disorientation.

His repeated use of false names and histories, along with his unsettling ability to inhabit these roles convincingly, suggests not just a moral flexibility but a deeper absence of self. By the time he confronts people who knew Heydon intimately—Reagan, Miranda, Badwan—he isn’t merely faking; he’s becoming a distorted version of the man.

This theme is exacerbated by the narrative’s ambiguity about whether anyone truly knew the real Heydon to begin with, and if “being” him is even possible anymore. The protagonist’s descent into the role reveals the hollowness of the social constructs around identity—wealth, family, power—all of which can be imitated or bought.

What is most haunting is how this impersonation leaves behind no original self to return to. By the novel’s end, Lynch no longer belongs to any life he once knew, including his own.

Power, Surveillance, and Control

Throughout the novel, institutions and individuals exert power through psychological manipulation, surveillance, and coercion. The manipulation of Heydon Pierce by corporate and clandestine actors illustrates how modern control is less about brute force and more about destabilizing reality itself.

Heydon is gaslit into questioning his memories, stalked by digitally manipulated symbols like magpies, and isolated from truth through strategic media erasure. This targeted campaign of destabilization culminates in his emotional collapse, showing the devastating impact of weaponized information.

Lynch, too, finds himself under constant threat—his passport stolen, his finances blocked, his movements tracked—suggesting that once marked, escape from institutional influence is nearly impossible. Entities like Hartson Holdings and The Agency operate beyond the reach of law or reason, creating a shadow state that engineers public narratives and silences truth through both economic power and emotional trauma.

Even minor characters like Dr. Kate Matten and Sebastien are enmeshed in this machinery, either as pawns or willing participants.

The psychological warfare waged on Heydon is not unique but systemic, a method for neutralizing those who threaten powerful interests. This theme is embodied in Lynch’s tattoo—an emblem that brands him as both a product and a target.

By the novel’s end, the realization dawns that there is no safe distance from these forces; survival requires participation in the very games one seeks to escape.

Family and Generational Trauma

The Pierce family stands as a fractured monument to wealth, grief, and generational damage. Heydon’s psychological decline is not only a product of external manipulation but also a consequence of internal family dynamics—particularly the death of his younger brother Theo, which haunts every member in different ways.

Miranda Pierce emerges as a matriarch both manipulative and helpless, someone who enforces rigid roles while failing to protect her children from collapse. Reagan is the emotionally calcified daughter who, despite her strength, is burdened by the expectation to preserve the family’s façade.

Bobbie’s wild instability reveals the cost of familial rejection and emotional neglect. Heydon, once the golden child, becomes the scapegoat, and eventually the sacrificial offering whose disintegration keeps the family machinery going.

The impersonation plot is therefore not just a thriller device but an allegory for how families force members into roles they must perform indefinitely. Lynch’s gradual immersion into the Pierce dynamic allows the reader to see how identity is shaped by expectation, guilt, and denial.

The family’s refusal to confront Theo’s death openly festers into a network of lies and psychoses that make Heydon’s mental collapse feel inevitable. Even Lynch, an outsider, becomes infected by the same sickness—by participating, he inadvertently adopts the family’s legacy of self-destruction masked as duty.

Morality in the Age of Deceit

The novel portrays morality as a moving target in a world dominated by performance, manipulation, and power. Lynch is not a hero; he begins the story fleeing from wrongdoing and continues to deceive everyone he meets.

Yet, he is portrayed as more ethical than many of the high-status characters—people who condone surveillance, gaslighting, and even murder to maintain power. Miranda justifies employing an impostor to face a criminal rather than seeking legal channels.

Sebastien engineers the cover-up of crimes for celebrity clients. Matthew Hartson manipulates a grieving son as part of a vendetta.

In contrast, Lynch’s moments of conscience—returning the stolen purse, protecting Bobbie, confronting those behind Heydon’s demise—suggest a fragmented but persistent moral compass. His eventual decision not to kill Bobbie and instead demand protection is not just a strategic move but a declaration that he will no longer serve others’ manipulative agendas.

In a world where institutions disguise their cruelty behind legality and wealth, Lynch’s raw, conflicted humanity stands out. This theme challenges the reader to consider how truth and justice function in environments built on artifice, and whether integrity is possible when survival requires lies.

Reality, Delusion, and Mental Deterioration

The novel blurs the boundary between psychological instability and manipulated delusion, particularly through the character of Heydon. His belief that his dead brother Theo might be alive is reinforced through manufactured symbols and impersonations, creating a hallucinatory landscape in which he cannot distinguish internal trauma from external deceit.

Lynch walks into this madness as a bystander, but slowly begins to feel its effects himself—questioning what’s real, who he can trust, and whether his own sense of identity is intact. The recurrence of distorted symbols, from magpies to surveillance glitches, reveals how perception can be controlled by those with access to technology and information.

Heydon’s videotaped confessions oscillate between paranoia and painful clarity, indicating a man deeply unwell but also deeply aware of the trap closing around him. This confusion is mirrored in Lynch’s journey as he moves through layers of lies and confronts a world where truth is deliberately obfuscated.

Reagan’s reluctance to face the implications of her mother’s behavior, Dr. Matten’s coerced silence, and the Hartsons’ detached cruelty all underscore a world where denial is a survival mechanism.

By the conclusion, it’s clear that mental deterioration in the novel is not a personal failing but the byproduct of a society engineered to produce madness in anyone who questions its order.

Redemption and the Possibility of Reconnection

Lynch’s arc is, in part, a search for meaning and redemption in the aftermath of moral compromise. The reappearance of Clare, the woman from his past, serves as a symbolic lifeline—someone who knew him before the web of lies began.

His journey through the Pierce family, his encounters with Bobbie, Reagan, and even Heydon’s ghost, push him to consider not just survival, but the possibility of restoration. Yet redemption is never clearly attainable.

The system he is entangled in does not forgive or forget; it monetizes, manipulates, and eliminates threats. Lynch’s choice to walk away—rejecting more violence, refusing to kill Bobbie, demanding self-protection—signals a moment of agency, a shift from passive tool to active participant in his own life.

His call to Clare is less about romantic closure than about reconnecting with a version of himself that predates the impersonation. It is a final attempt to reclaim humanity in a world that has persistently sought to erase or commodify it.

Whether this redemption is real or delusional is left ambiguous, but the gesture affirms Lynch’s refusal to vanish quietly. In a novel full of exploitation and artifice, choosing to seek truth—even at personal risk—becomes the most radical act of all.