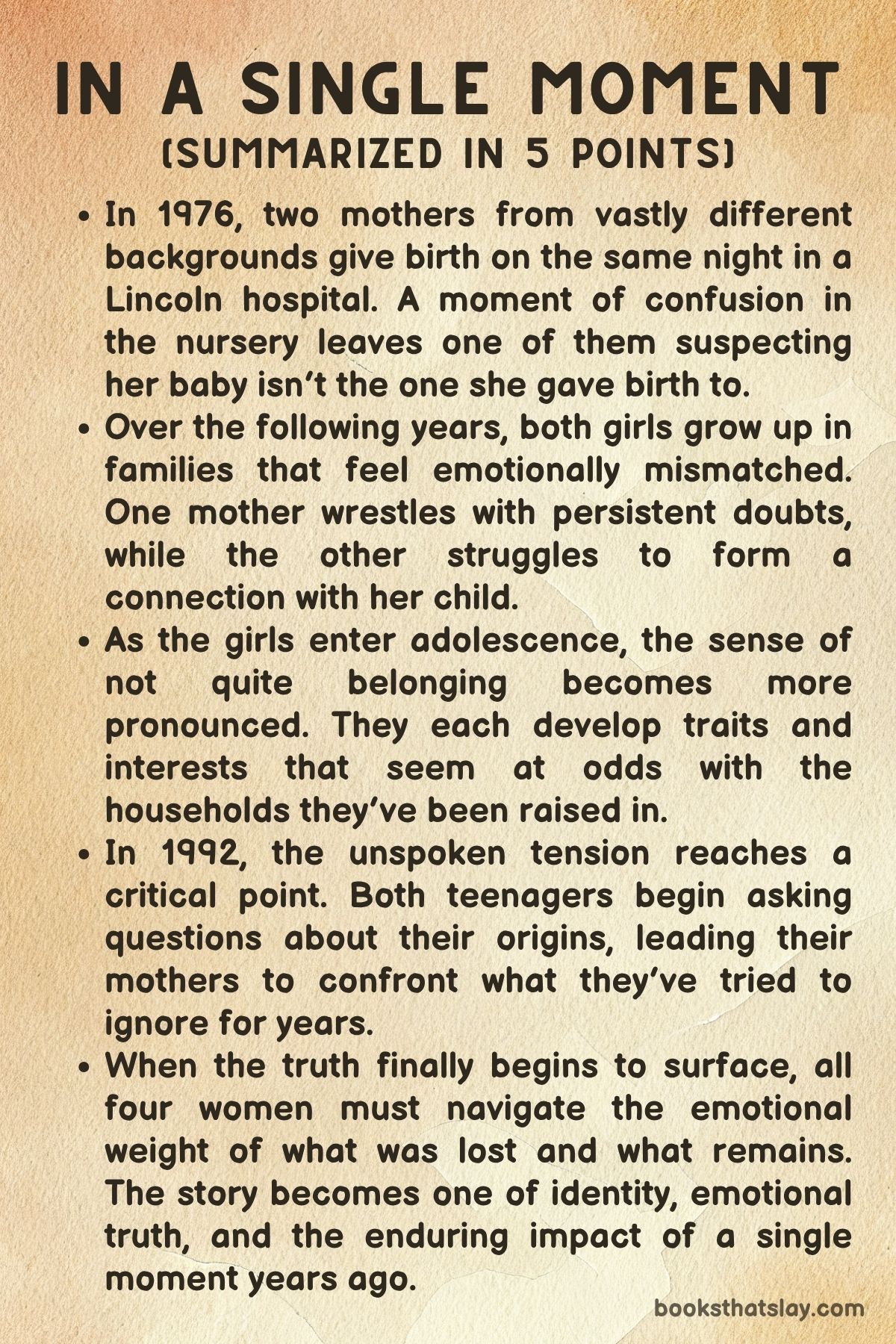

In a Single Moment Summary, Characters and Themes

In a Single Moment by Imogen Clark is a deeply emotional novel that explores how one seemingly minor decision can reshape the lives of multiple people forever. Set in England across several decades, the story centers on two families from vastly different social backgrounds who become linked by a mysterious event at a maternity ward in 1976.

Through alternating perspectives, the novel unpacks questions of identity, maternal love, and the lasting impact of secrets. Imogen Clark writes with sensitivity and subtlety, focusing more on internal struggles than dramatic twists.

What unfolds is not just a tale of a possible baby switch, but a thoughtful examination of how people cope with doubt, guilt, and belonging over time.

Summary

In the sweltering summer of 1976, two women give birth in a hospital in Lincoln, England. Michelle, a young working-class mother of four, is overwhelmed by her chaotic home life and inattentive husband, Dean.

Sylvie, poised and reserved, comes from a wealthier background and is married to Jeremy, a painter. Unlike Michelle, Sylvie is detached from her newborn daughter, Leonora, and uneasy about motherhood.

One night, both mothers allow their babies to be taken to the nursery. The next morning, Michelle takes home a baby she names Donna, a quiet, docile infant unlike her other children.

Over time, she becomes haunted by the idea that the baby may not be hers. Her suspicions grow when she notices differences in appearance and behavior.

She remembers that the baby came back from the nursery wearing different clothing and without a name tag. Despite confronting hospital staff, she receives no answers.

Unable to locate Sylvie, Michelle decides to live with her doubts. She focuses on raising her family the best she can, even as a quiet unease lingers in the background.

Five years pass, and Donna and Leonora grow up in separate households, each feeling slightly out of place. Donna is gentle and composed, traits that starkly contrast with her rowdy siblings and chaotic home.

Michelle’s concerns never fully disappear, though life’s demands push them into the background. Sylvie, meanwhile, remains emotionally distant from Leonora, who is anxious and withdrawn.

Sylvie often feels judged by her mother-in-law and trapped in a life that doesn’t feel natural. Both mothers sense something isn’t quite right with their daughters, but neither takes action.

By 1983, both girls are seven. The emotional gap between them and their mothers has not narrowed.

Michelle continues to love Donna, but feels something is missing in their bond. Sylvie, despite appearances, still struggles with her role as a mother.

Neither woman can fully silence her private doubts. But life continues to move forward.

In 1987, Donna and Leonora are preteens. Donna remains the quiet outsider in Michelle’s busy household.

Leonora continues to feel out of sync with her cultured but emotionally unavailable parents. Both girls begin to sense, in different ways, that they do not quite belong where they are.

The emotional dissonance is no longer confined to the adults. It begins to show in the girls themselves.

By 1992, both girls are sixteen and questioning their identities. Donna, drawn to books and self-reflection, feels increasingly alienated from her family.

A teacher encourages her to think beyond her background, sparking friction with Dean. Meanwhile, Leonora also begins to sense that her life has been built on something uncertain.

When she comes across a newspaper photo of Michelle, a strange recognition surfaces. Each girl begins independently searching for answers.

Their searches eventually lead to revelations. Michelle, overwhelmed by years of doubt, finally tells Donna her long-held suspicion that she might not be her biological daughter.

Sylvie, too, finds an old hospital letter referencing possible confusion during the nursery shift years ago. The truth emerges: Donna and Leonora were switched at birth.

The girls finally meet, and although their reunion is tense and emotional, it brings a strange kind of clarity. Each recognizes something of herself in the other.

They don’t reject their families, but they begin to build a cautious connection. They understand that both love and identity can be complex and non-binary.

Seven years later, both women are in their twenties. The families have found a fragile peace.

Michelle and Sylvie have come to terms with the past. Donna and Leonora continue to define their own paths.

The moment that changed everything did not destroy them. It taught them what truly matters.

Characters

Michelle

Michelle is introduced as a working-class mother of four, grappling with the demands of parenthood, poverty, and a largely absent, emotionally unengaged husband. Her resilience is evident from the start—she gives birth amid exhaustion and social constraints, determined to keep her family together.

What distinguishes Michelle is her deep maternal instinct, which ironically becomes the source of her greatest torment: the gut-level feeling that the baby she brought home, Donna, isn’t her biological daughter. Over the years, Michelle’s unease evolves into quiet desperation.

She tries to suppress her suspicions for the sake of family stability, but the internal conflict seeps into her relationship with Donna. Despite raising her lovingly, Michelle can never shake the subtle sense of disconnection, and this guilt eats away at her.

She is portrayed as emotionally intelligent yet burdened by her environment—stuck between what she feels is true and what she’s told is irrational. When she finally confesses her fears to Donna, it’s not an act of abandonment but one of integrity.

Michelle’s growth is marked by her ability to confront the painful truth and seek reconciliation. By the end of the novel, she finds peace in embracing the emotional bonds that transcend biology.

Sylvie

Sylvie is a woman caught in the web of societal expectations, emotional repression, and personal dissatisfaction. Unlike Michelle, her struggle is less about survival and more about performance—trying to appear as the ideal mother and wife within a polished, upper-class existence.

Her lack of maternal instinct is striking and deeply felt, not only by herself but also by those around her. Sylvie is emotionally distant from Leonora, the daughter she raises, whom she treats more like an obligation than a joy.

This disconnection is not born of cruelty but of confusion and inadequacy. Sylvie often feels like an imposter in her own life, especially under the critical eye of her mother-in-law Margery.

Her detachment becomes a central emotional thread, exposing how privilege can mask deep unhappiness. Over time, Sylvie changes subtly but meaningfully.

She softens, reflects, and ultimately comes to terms with the truth of the baby swap. She never transforms into a conventionally warm or affectionate figure, but she gains self-awareness and a certain grace in allowing Leonora the space to redefine their relationship.

Sylvie’s arc is one of quiet redemption—not through dramatic gestures but through an honest, gradual acceptance of her limitations and a willingness to grow beyond them.

Donna

Donna is the emotional heart of the novel, embodying the quiet tragedy of misplaced identity. Raised in a bustling, noisy working-class household, she is the antithesis of her environment—gentle, introspective, and sensitive.

Her alienation is felt early on, not just by Michelle but by Donna herself, even if she can’t articulate it as a child. As she matures, Donna becomes more attuned to her differences and leans into them.

She develops academic interests and a refined sensibility that further set her apart from her family. Her journey is one of self-discovery, as she grapples with the growing realization that she might not belong where she was raised.

Yet, Donna never harbors bitterness; instead, she demonstrates emotional maturity, seeking truth without resentment. When Michelle finally reveals the truth, Donna is shaken but not shattered.

Her reaction is tempered by a lifetime of quiet knowing. She becomes the bridge between two worlds, navigating a relationship with her biological roots while honoring the love she received growing up.

By the novel’s end, Donna emerges as a woman who has reclaimed her narrative. She chooses how to integrate the fragmented pieces of her identity into a cohesive self.

Leonora

Leonora is a portrait of emotional displacement. Raised in an affluent home with artistic parents, she nonetheless feels invisible.

Unlike Donna, Leonora is not given the benefit of noise and chaos to mask the emptiness—her home is calm, elegant, and emotionally hollow. Sylvie’s coldness and Jeremy’s artistic aloofness leave Leonora to raise herself emotionally.

This results in a shy, reserved, and somewhat guarded young woman. Her internal world is rich and conflicted; she is intelligent and observant but lacks the support needed to truly blossom.

As she grows, Leonora begins to suspect that something about her origins doesn’t quite add up. Her reaction to discovering the truth is quiet but powerful, rooted in years of subtle emotional evidence.

She is less confrontational than Donna but equally determined to understand who she is. Leonora’s arc is marked by grace and introspection.

She doesn’t reject her past but seeks to understand it. Her eventual bond with Donna, and her cautious redefinition of her relationship with Sylvie, shows her strength in forging identity not through rejection but through careful reintegration of truth.

Dean

Dean is a consistent figure of emotional inadequacy throughout the novel. From the moment of Donna’s birth, he is portrayed as distant, dismissive, and emotionally unavailable.

His idea of fatherhood is rooted in presence rather than connection—he’s there physically, but rarely meets the emotional needs of his family. Dean minimizes Michelle’s concerns, laughs off her suspicions, and refuses to engage with the emotional undercurrents of their household.

His character represents a certain archetype: the man overwhelmed by domestic life, choosing avoidance and denial over intimacy. He never truly evolves, remaining largely blind to the gravity of what has happened under his own roof.

By the novel’s end, he is more a static backdrop than a dynamic force. He is a reminder of how emotional passivity can be just as harmful as active neglect.

Jeremy

Jeremy is a more complex counterpart to Dean—also emotionally unavailable, but under the guise of artistic sensitivity. He loves from a distance, often lost in his painting studio, immersed in creativity rather than family.

His affection for Leonora is real, but shallow, rooted in aesthetics and occasional indulgences rather than deep understanding. Jeremy’s avoidance is subtler than Dean’s but just as consequential.

He fails to notice the strain in Sylvie, the alienation in Leonora, and the quiet implosion of their family dynamic. Jeremy’s arc is less about change and more about exposure.

As the truth emerges, he must confront the limitations of his role as a father and husband. Yet he remains emotionally removed.

Tina

Tina, Michelle’s eldest daughter, is a stabilizing presence in Donna’s life. From early childhood, she treats Donna with affection and protectiveness, almost like a surrogate mother.

While not a central character, Tina represents the power of sibling love to bridge emotional gaps. Her relationship with Donna is uncomplicated and pure.

She offers Donna a sense of belonging even in a family where she otherwise feels like an outsider. Tina’s loyalty and warmth serve as emotional ballast for Donna during turbulent times.

Margery

Margery is the embodiment of judgmental upper-class rigidity. As Jeremy’s mother, she frequently critiques Sylvie and exerts subtle pressure on how Leonora should be raised.

Her constant interference exacerbates Sylvie’s insecurities. This contributes to Sylvie’s emotional detachment.

Margery is not cruel, but her controlling nature and narrow standards of parenting reinforce the emotional sterility in the Fotherby-Smythe household. She plays a minor but symbolically important role in highlighting generational and class-based expectations of motherhood.

Themes

Motherhood and Maternal Identity

The novel In a Single Moment explores motherhood as something far more complicated than a simple biological bond. Through the experiences of Michelle and Sylvie, it reveals the emotional burden and ambiguity often buried beneath this role.

Michelle, overwhelmed by the chaos of working-class life, initially embraces motherhood with instinct and resilience. Yet her sense of maternal identity is shaken by her enduring suspicion that Donna is not her biological child.

The emotional distance she feels from Donna, despite her efforts, never fully closes. This fuels her guilt and makes her relationship with Donna feel forced and conditional.

Sylvie, in contrast, struggles with maternal connection from the beginning. Her upper-class life provides comfort but lacks emotional depth, and she never develops the closeness with Leonora that she longs for.

Her inability to bond becomes a constant source of internal shame. She performs the duties of parenting without truly feeling like a mother.

In both women’s experiences, motherhood is portrayed as fraught with self-doubt, disconnection, and unmet expectations. Neither the comforts of class nor the strength of instinct provide immunity from the emotional weight of this role.

The book challenges the assumption that biology guarantees closeness. It asks whether being a mother is about birthing a child or building a relationship with one—and whether it’s ever possible to feel like enough.

Identity and Belonging

In a Single Moment explores identity through the contrasting lives of Donna and Leonora. Raised in homes that do not reflect their inner personalities, both girls grow up feeling estranged from the families who love them.

Donna’s bookishness and quiet ambition place her at odds with her boisterous working-class siblings. She is alienated by her environment, never fully fitting in, despite her affection for Michelle and the others.

Leonora, meanwhile, feels equally out of place in a world of elegance and artistic pretension. She craves warmth and understanding but instead grows up in emotional isolation.

As teenagers, both begin to act on their feelings of otherness. Their investigations into the truth of their birth confirm what they’ve always sensed—that they belong elsewhere.

However, the novel goes further than revealing a switched identity. It suggests that identity is built over time through lived experience, not just determined by blood.

Even after discovering the truth, the girls are not fully liberated or defined by it. They are left to reconcile the lives they lived with the lives they might have had.

Belonging, the book implies, is not a fixed condition. It can be found in multiple places, even in families where one might not have begun.

Class and Social Inequality

Class difference shapes every part of In a Single Moment, not just the physical environments of the characters, but their emotional lives as well. It determines who is heard, who is believed, and who is left to question themselves in silence.

Michelle and Dean live under financial pressure, sharing a cramped house and juggling the needs of four children. Their love is real, but it is battered by exhaustion and stress.

Michelle’s suspicions are repeatedly dismissed, often because she lacks the social capital to demand answers. Her instincts are labeled anxiety rather than insight.

Sylvie and Jeremy, by contrast, live in an ordered world of comfort and cultural currency. But their wealth does not protect them from emotional disconnection.

Sylvie’s failures as a mother are less visible and more internalized. She suffers in private, afraid to admit what she feels to anyone—even to herself.

The novel highlights how class does not insulate people from pain but shapes the way that pain is processed and perceived. Emotional struggle wears a different mask in each household.

Even the healthcare system fails Michelle because of who she is and how she presents. Her voice is quieted not because she lacks feeling but because she lacks status.

The book asks readers to consider how deeply inequality influences not just access to resources but access to emotional validation. Class divides are not just about money—they are about who gets to speak, and who is taken seriously when they do.

Emotional Repression and Silence

Silence is a recurring and corrosive force in In a Single Moment. It affects all the characters, shaping their relationships and decisions in damaging ways.

Michelle senses early on that something is wrong. But her concerns are muted—first by others, and eventually by her own reluctance to confront a painful possibility.

Years of avoidance create a fragile bond with Donna. Their relationship becomes a quiet compromise between love and uncertainty.

Sylvie’s silence is rooted in shame and fear of judgment. She avoids emotional honesty, even in her most private moments.

Her home is filled with conversations that say nothing. Jeremy, while kind, remains emotionally unavailable, and Leonora is left to grow up in a house that offers little warmth.

This collective failure to speak leaves lasting damage. The longer the truth remains buried, the harder it becomes to repair the emotional distance it creates.

When revelations finally come, they do not heal everything. But they create a space where genuine conversation can begin.

The novel suggests that silence, while often chosen for protection, ultimately isolates. Only truth—however uncomfortable—offers the possibility of connection and growth.

The Irreversibility of Choice

The idea that a single moment can change everything is central to In a Single Moment. The novel shows how decisions made quickly, under pressure or fatigue, can echo across decades.

The baby switch itself may have been accidental. But the real damage comes from the choices made afterward—the choice not to ask, not to question, not to speak.

Michelle’s silence becomes a burden she carries for sixteen years. Sylvie’s decision to ignore her instincts leaves her trapped in a role she cannot fully inhabit.

As the girls grow older, their sense of dislocation forces the past back into the present. They begin to ask the questions their mothers never could.

These choices cannot be undone. Donna and Leonora cannot return to the lives they were meant to have. They can only confront the lives they did have and find meaning within them.

The book does not offer a perfect resolution. There is no justice to be served, only understanding to be reached.

Still, the later choices the characters make—choosing honesty, choosing to meet, choosing to build new relationships—show that the past, while fixed, does not have to define the future.

The theme of irreversibility is not fatalistic. It is a reminder of the weight our actions carry and the resilience required to live with their consequences.