Into the Woods Summary, Characters and Themes

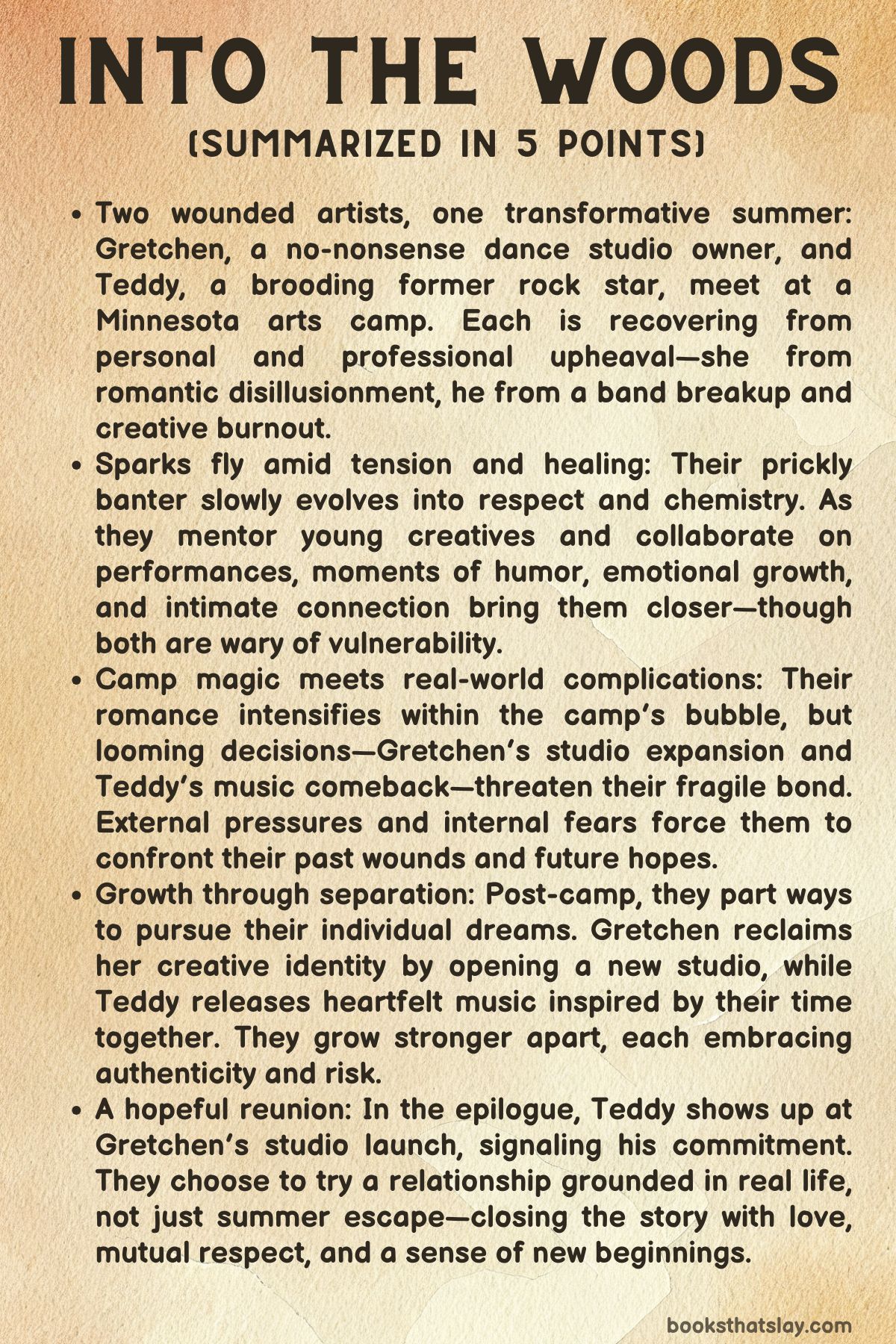

Into the Woods by Jenny Holiday is a contemporary romance that explores what happens when two creatively burned-out individuals seek solace in an artists’ retreat and unexpectedly find connection. The story follows Gretchen Miller, a fiercely independent dance studio owner experiencing a personal and professional crossroads, and Teddy Knight, a rock bassist recovering from band betrayal and emotional scars.

What begins as a summer detour at a remote Minnesota camp soon becomes a transformative journey. Through reluctant collaboration, artistic rediscovery, and emotional vulnerability, Gretchen and Teddy find not only renewed purpose in their work but also the unexpected possibility of love and partnership.

Summary

Gretchen Miller has built her life on the foundation of independence and grit. Raised in a financially unstable household with a dreamer father and a hardworking mother, she vowed early never to rely on anyone but herself.

Seventeen years into owning her own dance studio in Minnetonka, Gretchen is professionally successful, owns a home, and is expanding her business. Yet despite her achievements, an undercurrent of dissatisfaction lingers.

Her love life is a string of disappointments, and after a humiliating final date with a pompous rock star named Scott, she decides to give up dating altogether.

Her best friend Rory, who is pregnant and persuasive, encourages her to take a temporary summer job as an artist-in-residence at Wild Arts, a remote Minnesota arts camp. The position is a last-minute fill-in for a famed dancer and offers Gretchen a chance to escape routine, reflect, and realign.

She accepts on impulse, hoping to retreat from stress and men alike. What she doesn’t expect is to meet Teddy Knight, the bassist of Scott’s band, who has also landed at Wild Arts trying to recover from personal and professional implosion.

Their connection is unknown to Gretchen at first, but Teddy instantly recognizes her as “Scott’s final date.

Teddy is emotionally raw from the abrupt breakup of his band, Concrete Temple, and the betrayal of his former bandmate Scott, who secretly launched a solo project behind his back. Teddy’s identity as a musician is shaken, and at the camp, he struggles to find his creative voice.

He’s closed off and acerbic, preferring isolation in his cabin to group dinners. Gretchen is equally wary, finding his brooding demeanor and minor celebrity status irritating.

Their first encounters are awkward, including one where Gretchen accidentally sees him swimming naked at night.

Despite their misgivings, the forced proximity and shared responsibilities of camp life begin to soften the edges between them. Gretchen bonds with the campers, finds joy in not being in charge for once, and starts exploring new ideas for choreography.

Teddy, meanwhile, begins mentoring musically inclined teens, especially Anna, a talented banjo player whose fresh take on old classics rekindles his creative spark. As the weeks progress, he starts composing again, exploring a new folk-rock style distinct from his band’s previous sound.

The emotional core of their dynamic unfolds in quiet conversations and shared vulnerabilities. Teddy opens up about his emotionally distant mother and the symbolic trauma of the “lemon tree” she loved more than her children.

Gretchen, though initially self-protective, shares her own emotional wounds—stories of failed dates, career pressure, and her internal conflict over whether her life’s work has any real meaning. Their physical relationship, sparked by a mutual sense of safety and curiosity, grows into something emotionally intimate, though neither initially admits it.

Gretchen is inspired to create a new performance based on Little Women, casting campers to explore themes of poverty and sisterhood, which resonate deeply with her own upbringing. Teddy begins supporting her work and contributes ideas for music and casting.

He critiques the “girl” songs used in class, prompting thoughtful discussions about feminism and agency in performance. Gretchen starts to question the limitations of her business model and dreams beyond Miss Miller’s as she regains artistic momentum.

Teddy returns home for a brief visit, where he finds that his ex, Karlie, has moved out and started a new life, including a pregnancy. Their farewell is cordial and affirming.

More importantly, Teddy supports his younger sister Auden through her first therapy session, where they share emotional truths about their childhood neglect. Teddy resolves to continue therapy with her, marking a significant step toward healing.

Back at Wild Arts, Teddy dives into songwriting, mentors Anna further, and finishes a solo album. He forms a bond with Marion, the camp director, who encourages him to pursue producing.

When Marion needs someone to chaperone Anna for a studio session, she suggests Gretchen. However, Gretchen has abruptly ended her relationship with Teddy, choosing to focus on her business instead of risking further emotional entanglement.

Still in love, Teddy seeks advice from his friend Jack, and inspired by Say Anything, he makes a grand gesture. He crashes Gretchen’s birthday party with a boombox blaring “Moon River” outside her bedroom window.

Though stunned, Gretchen listens. Teddy admits his earlier approach was flawed but sincere—he loves her.

She admits she feels the same, and the emotional walls between them begin to fall.

Months later, Gretchen has transformed her professional identity. She flips her original building and uses the proceeds to fund a modern dance company.

Her choreography becomes bolder, including a “trench dance” symbolizing female resistance. Teddy is now her partner in every sense—emotionally and creatively.

He splits his time between Minneapolis and New York, supporting her endeavors while also pursuing his own. His acoustic single, inspired by Gretchen, becomes a hit.

Their relationship is grounded in truth rather than fantasy. They argue, compromise, and support one another’s ambitions without losing themselves.

The story ends with Gretchen inviting Teddy to move in, a gesture that underscores how far they’ve come. What began as a retreat becomes a starting point for a shared life rooted in creativity, honesty, and mutual growth.

Into the Woods concludes not with a fairy tale ending, but with the promise of real love built on hard-earned trust and shared purpose.

Characters

Gretchen Miller

Gretchen Miller is a multifaceted protagonist whose journey in Into the Woods encapsulates themes of independence, creative transformation, and emotional reawakening. Raised in a household marked by love but deep financial instability, she developed a fierce self-reliance early in life.

Her father’s delusions of grandeur and inability to provide consistent support left an indelible mark, propelling Gretchen toward a life defined by practicality and self-discipline. This backstory informs the creation of her successful dance studio, Miss Miller’s of Minnetonka, which stands as both a literal and symbolic representation of her personal agency.

At the outset, she is pragmatic to the point of emotional austerity, shutting down her romantic prospects and focusing solely on expanding her business. Yet beneath this resolve lies a question of existential fulfillment—a slow-burning dissatisfaction that her achievements, impressive as they are, may not be enough.

Gretchen’s arc truly begins when she accepts a temporary summer position at Wild Arts camp, where the structured world she built begins to unravel in the best possible way. Initially determined to embrace her identity as a midlife woman disengaged from romance, she ends up confronting the very emotions she tried to suppress.

Her dynamic with Teddy challenges her self-imposed boundaries, forcing her to reckon with the difference between survival and flourishing. Gretchen also undergoes an artistic awakening, rediscovering her passion for choreography and reevaluating what empowerment means—especially when she fires a disrespectful student and recasts her narrative with an all-girl ensemble.

Her transformation is profound: from guarded and goal-oriented to emotionally present and creatively liberated. By the end, she is no longer just a successful businesswoman; she is a visionary artist, a partner, and someone who chooses vulnerability over control, proving that strength and softness can coexist.

Teddy Knight

Teddy Knight emerges as a complex and emotionally rich character whose journey parallels Gretchen’s in profound ways. A bassist reeling from the betrayal of his former bandmate Scott and the collapse of Concrete Temple, Teddy seeks refuge at the Wild Arts camp not just to escape the noise of fame, but to confront the void left in its wake.

His initial demeanor is brusque, standoffish, and imbued with a quiet despair. He is haunted by unresolved childhood trauma—specifically, the emotional neglect of his mother, symbolized by the haunting memory of a lemon tree she prioritized over her children.

This inner pain has long stunted his emotional growth and artistic output, leaving him paralyzed in both love and music. Yet within the solitude of the woods, and through unlikely mentorship roles and candid moments with Gretchen, Teddy gradually begins to shed his defenses.

His connection with Gretchen becomes a catalyst for healing. Their evolving bond, marked by raw conversations and mutual respect, allows Teddy to open up in ways he previously thought impossible.

His mentorship of a teenage musician, Anna, rekindles his artistic passion, prompting him to explore a solo project that reflects his authentic self—folk-inflected, emotionally resonant, and entirely different from his past work. The turning point in his arc comes when he chooses to face his past rather than flee it, attending therapy with his sister Auden and finally confronting the emotional debris of their upbringing.

In reclaiming his voice both musically and personally, Teddy steps into a version of manhood defined not by bravado but by emotional clarity, empathy, and courage. His eventual relationship with Gretchen, grounded in creative partnership and mutual healing, marks the culmination of a redemptive journey where love is not an escape but a commitment to presence and growth.

Rory

Rory, Gretchen’s best friend, plays a pivotal—if supporting—role in facilitating the protagonist’s transformation. As a pregnant and grounded figure in Gretchen’s life, Rory represents stability, familial evolution, and emotional encouragement.

It is through her gentle persuasion that Gretchen agrees to attend Wild Arts, a decision that becomes the story’s inflection point. While Rory doesn’t command much narrative space, her presence is vital as an emotional anchor and voice of reason.

She understands Gretchen in ways few others do and nudges her toward a journey of vulnerability and creativity. Rory’s role underscores the importance of female friendship and chosen family, offering emotional scaffolding during Gretchen’s retreat and reawakening.

Her influence serves not only as a plot device but as a symbol of enduring, supportive sisterhood.

Anna

Anna is a secondary but symbolically powerful character whose presence catalyzes emotional and artistic breakthroughs for Teddy. A teenage banjo prodigy with a fresh and unfiltered approach to music, Anna becomes both muse and mentee.

Her confidence, vulnerability, and talent remind Teddy of why he became a musician in the first place, offering a mirror through which he can rediscover his own artistic joy. Through Anna, Teddy steps into the role of mentor and producer, finding meaning not in the spotlight but in nurturing talent.

She represents the next generation of artists—unburdened by cynicism and full of possibility. Her relationship with Teddy highlights the redemptive power of teaching, collaboration, and creative mentorship.

Auden

Teddy’s sister, Auden, appears briefly but leaves a lasting impact through the emotional depth of her shared history with Teddy. Bound by a childhood marked by neglect and silence, the siblings’ reconciliation is one of the novel’s emotional high points.

Auden, stoic and long-suffering, finally breaks down during her first therapy session, revealing the profound emotional wounds she has carried. Teddy’s offer to attend therapy alongside her signifies a shared commitment to healing and accountability.

Their bond is raw, honest, and emblematic of the way trauma can both fracture and forge unbreakable ties. Auden helps humanize Teddy, giving readers a deeper glimpse into his compassion, guilt, and capacity for growth.

Together, they begin to dismantle generational pain, choosing understanding over silence.

Scott and Karlie

Scott, though a relatively minor figure, serves as an inciting force in both Teddy and Gretchen’s stories. As Gretchen’s final disappointing date and Teddy’s backstabbing bandmate, Scott is the embodiment of performative charm and creative betrayal.

His actions indirectly push both protagonists toward reinvention. Karlie, Teddy’s ex, is a more nuanced figure.

Her pregnancy and decision to leave their shared life behind represent a clean break and a mature reassessment of values. Her calm, respectful closure with Teddy opens emotional space for his new relationship with Gretchen.

Both characters serve as emotional mirrors, reflecting what the protagonists no longer want in their lives and relationships.

Together, this ensemble supports a nuanced exploration of growth, healing, and rediscovery, illustrating how personal reinvention is not a solo act but a collaborative journey of truth, connection, and creation.

Themes

Midlife Reinvention and the Pursuit of Fulfillment

Gretchen’s journey in Into the Woods is a layered exploration of what it means to confront life at a crossroads. Her professional accomplishments have brought her financial security, independence, and public validation.

Yet, an undercurrent of discontent threatens the foundation of that success. The question once voiced by her father—“Is this all there is?

”—echoes through her internal monologue, highlighting the dissonance between outward achievement and inward satisfaction. Her decision to step away from dating and shift her focus toward Miss Miller’s 2.

0 might seem like an assertion of agency, but it also masks deeper uncertainty about what she wants from life. When she accepts a temporary position at Wild Arts, it marks a pivotal departure from structure and control, thrusting her into an unfamiliar environment where productivity and busyness can no longer shield her from introspection.

Her time at the camp doesn’t simply serve as a break from routine but forces her to reckon with her evolving identity as a woman, artist, and human being. Through physical space and emotional distance from her usual surroundings, she comes face-to-face with what she’s been avoiding: the possibility that her life might need to look very different to feel truly fulfilling.

Creative Awakening Through Collaboration

Artistic rebirth is a powerful theme threaded through both Gretchen’s and Teddy’s arcs. Each arrives at Wild Arts emotionally depleted, creatively stalled, and unsure of what comes next.

Gretchen, used to being the one in control of her studio and its routines, is disoriented by the open-endedness of camp life but finds a new spark when she begins choreographing an adaptation of Little Women. Her creative instincts are reawakened not by ambition but by curiosity and connection.

The camp’s dancers become her mirror, allowing her to explore questions of class, girlhood, and belonging through movement. Teddy, likewise, begins the story paralyzed by betrayal and artistic grief.

The loss of his band—and the duplicity of Scott—cuts deeper than professional disappointment; it severs his sense of identity. At camp, he slowly begins composing again, initially in solitude and later through his mentorship of Anna, a gifted teen musician.

The collaborative energy between him and Gretchen, sometimes playful and sometimes argumentative, creates a space where inspiration can thrive again. Their eventual partnership, both romantic and creative, becomes a testament to how healing can come through shared artistic purpose.

It isn’t just about producing something new—it’s about rediscovering why the act of creation matters.

Emotional Intimacy and Vulnerability

The romantic trajectory between Gretchen and Teddy evolves through subtle, emotionally intimate exchanges rather than dramatic declarations. Their relationship is not immediately romantic in nature; instead, it begins with friction, suspicion, and defensive banter.

What allows it to grow is the gradual erosion of those defenses. Both characters carry emotional wounds—Gretchen’s rooted in years of disillusioning romantic encounters, Teddy’s in his fractured childhood and recent heartbreak.

The camp becomes their emotional laboratory, a place where their armor is no longer necessary or sustainable. In quiet conversations, accidental moments of connection, and even physical vulnerability (as in the scene where Gretchen sees Teddy swimming naked), they begin to see and be seen.

Their bond is not forged in traditional romance tropes, but in mutual respect, curiosity, and the safety of being their unvarnished selves. The emotional honesty they achieve by the end of the story is not about fixing each other, but about choosing to witness and honor the other’s growth.

Their relationship becomes not a rescue mission but a shared experience of healing.

Feminine Strength and Redefining Power

Gretchen’s arc reclaims the meaning of feminine power by challenging conventional ideas of success and strength. She begins the story proud of her self-sufficiency, a badge earned through years of tireless work and sacrifice.

But that strength, while admirable, has hardened into isolation. Her interactions with others at Wild Arts, especially the younger girls and Teddy, reveal that power can also exist in softness, creativity, and openness.

Her decision to remove a disrespectful male student from her Little Women dance project and replace him with a female ensemble is not just a disciplinary act—it’s a symbolic re-centering of women’s voices. Later, when she returns to Minneapolis and reinvents her studio into a modern dance company with a bold new vision, she claims her place as both artist and leader on her own terms.

Her choreographed trench dance, representing female resistance, is an embodiment of this new power: expressive, unapologetic, and rooted in truth. Gretchen doesn’t shed her ambition—she redefines it.

The story affirms that female empowerment doesn’t require the rejection of intimacy or vulnerability. Instead, it arises from a deeper alignment with one’s authentic desires and values.

Healing from Family Trauma

Teddy’s childhood experience—marked by maternal neglect and emotional deprivation—casts a long shadow over his adult relationships and creative expression. His mother’s fixation on a lemon tree while ignoring her children’s needs becomes a haunting metaphor for misplaced care and unresolved grief.

Returning to this memory through music, especially the symbolic significance of the song “Lemon Tree,” allows Teddy to begin the process of emotional reckoning. His relationship with his sister Auden, often held at a polite emotional distance, deepens as they begin therapy together.

These moments are not grand catharses, but quietly powerful acknowledgments of shared pain. The novel suggests that trauma doesn’t vanish through confrontation alone; it requires patience, accountability, and a willingness to sit with discomfort.

Teddy’s emotional growth—particularly his willingness to be open with Gretchen, to fail at communication and try again—signals a break in the generational pattern. He may never “fix” his childhood, but he can choose not to let it dictate the rest of his life.

His love for Gretchen and his artistic revival emerge not in spite of his trauma, but through his decision to confront it.

The Redemptive Potential of Temporary Spaces

The setting of Wild Arts functions as more than a backdrop; it is a transformative space where both Gretchen and Teddy step outside the structures that have defined and limited them. Removed from the demands of the outside world—Gretchen’s studio, Teddy’s music industry pressures—they are allowed to experiment, falter, and rebuild.

This “in-between” setting fosters a kind of psychological permission to explore the sides of themselves they’ve long buried. For Gretchen, it’s the creative visionary she’s set aside in favor of managerial competence.

For Teddy, it’s the tender, thoughtful mentor who was silenced by ego-driven band dynamics. The ephemeral nature of the camp paradoxically gives them clarity about what they want in the long term.

What starts as a temporary detour becomes the crucible through which lasting change is forged. When they leave, they carry the lessons and momentum with them—not as souvenirs, but as the foundation for their next chapters.

In this way, Into the Woods offers a hopeful message: sometimes, the most unexpected environments can offer the truest paths to clarity, purpose, and connection.