Is a River Alive Summary and analysis

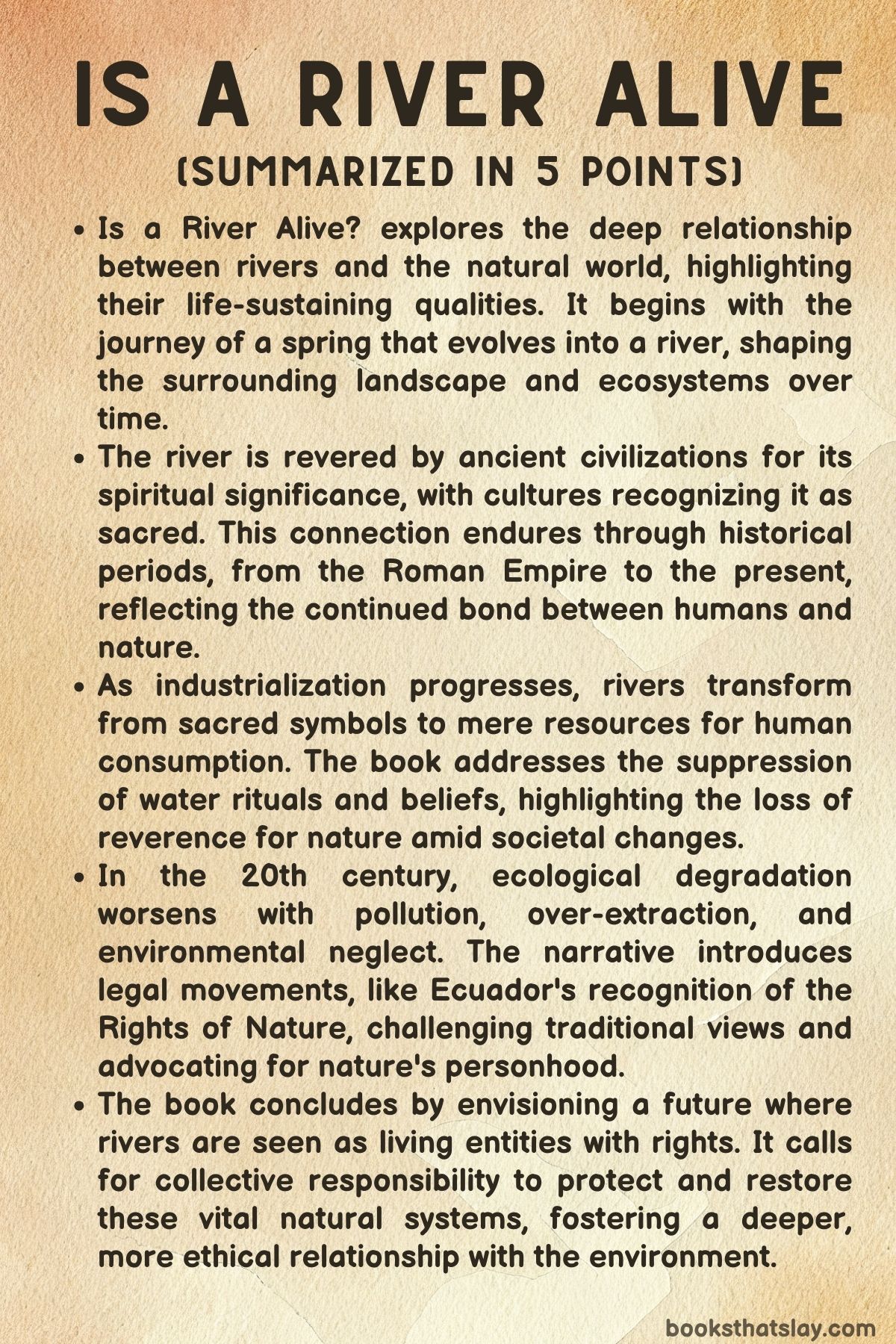

Is a River Alive by Robert Macfarlane is a profound exploration of the intricate and often overlooked relationship between humans, rivers, and the natural world. Through his exploration, Macfarlane delves into the spiritual, ecological, and historical significance of rivers, questioning what it means for a river to be alive.

This narrative is a journey through time and space, tracing the birth of a river from a spring to its eventual journey to the sea, revealing the human connection to these waterways across centuries. The book blends personal reflections with historical accounts and ecological insights, proposing a vision of the future where rivers are recognized not only as vital resources but as living entities with their own rights.

Summary

The journey begins thousands of years ago with the birth of a spring from the chalk hills, marking the beginning of a river’s life. This spring eventually transforms into a stream and later becomes a mighty river, flowing through a landscape shaped by ancient glaciers.

Over time, the river not only sustains life but also influences the very land through which it flows. Its crystal-clear water provides resources for ancient civilizations, who come to the river for sustenance and craft tools from the flints that scatter the ground around it.

As human civilizations evolve, the river becomes more than just a physical resource. It grows sacred in the eyes of ancient peoples, who worship it as a god, connecting human life to the rhythms of nature.

The river’s spiritual importance continues through various historical eras, from the rise of the Roman Empire to the Middle Ages and beyond. During these times, water rituals and beliefs tied to the river persist, although they begin to face suppression as industrialization and the Reformation lead to a shift in society’s views on nature.

The narrative transitions to the modern era, where human activities increasingly exploit rivers. The development of cities, alongside the rising demand for resources, turns rivers into mere utilities, stripping them of their sacred status.

In the 20th century, further environmental degradation occurs due to wars, industrialization, and pollution. The river becomes a symbol of the ongoing ecological crisis, illustrated through the shrinking Cam River, over-extraction of water, and pollution.

These issues highlight the fragile relationship between humanity and rivers, a bond that has been strained over the centuries.

However, in the face of environmental neglect, there is a movement that seeks to restore the reverence once held for rivers. This movement pushes for a radical rethinking of nature, advocating for the recognition of rivers and other natural entities as living beings with rights.

Legal frameworks like the “Rights of Nature” movement, exemplified by the landmark legal recognition of nature’s rights in Ecuador, propose that ecosystems, such as rivers, should not merely be seen as resources for human exploitation but as entities that deserve legal protection. The recognition of the Whanganui River in New Zealand as a legal person provides a powerful example of this shift in perspective.

Through this journey, the author also explores the personal emotional connection humans have with rivers. Macfarlane’s reflections highlight the deep spiritual bond people feel toward these waterways, a bond that has been neglected but can be reclaimed.

The narrative ends on a hopeful note, imagining a future where rivers are recognized as living beings with their own rights. This vision includes communities working together to restore and preserve the health of rivers, just as individuals have the capacity to heal themselves.

It calls for a return to a forgotten connection with nature, promoting a future where humans and the environment are harmoniously intertwined.

The story of the river is not just one of survival, but of mutual respect between humans and nature. Rivers shape the land, sustain life, and provide a deep source of meaning that transcends their role as mere physical resources.

The movement to grant legal personhood to rivers is not merely a legal reform; it is part of a cultural revolution aimed at recognizing the intrinsic value of nature. This shift, while challenging traditional systems of law and economics, holds the potential to foster a more ethical, sustainable relationship between people and the environment.

Macfarlane’s personal journey through the history of rivers and their changing relationship with humans is both a call to action and a reflection on the deeper spiritual and ecological connections that define our world. By recognizing the aliveness of rivers, and acknowledging their rights, society can begin to restore the balance that has been lost through centuries of exploitation.

The author’s vision is not one of hopelessness, but of possibility—an opportunity to reclaim the reverence for nature that has been absent for so long, and to build a future in which nature is seen as a partner, not a resource. This perspective offers a radical rethinking of how humanity might approach environmental issues, placing the rights of nature at the heart of global conservation efforts.

Key People

Giuliana

Giuliana, a mycologist, plays a pivotal role in the journey through Los Cedros, an ancient and biodiverse cloud forest in Ecuador. Her expertise in fungi provides a unique lens through which to view the intricate life forms of the forest.

While the narrator’s affinity lies with birds, Giuliana’s keen observation of the fungal networks beneath the forest’s surface allows the group to appreciate a lesser-known aspect of nature’s complexity. Her work is not just scientific but also deeply connected to the spiritual and ecological significance of the forest.

Giuliana’s focus on the unseen ecosystems, such as the mycelial networks, highlights her understanding of the interconnectivity of all life forms and their vital roles in the forest’s well-being.

César

César, an environmentalist, embodies the spirit of resistance against the exploitation of natural resources. His role in the expedition through Los Cedros connects directly with his broader mission to protect threatened ecosystems.

As a defender of the forest, César is invested in ensuring that the environmental rights recognized by Ecuador’s constitution are upheld. He stands as a voice of the forest, advocating for the legal recognition of nature’s inherent rights and ensuring that nature is treated not just as a resource, but as an entity deserving of protection.

César’s journey through the forest is both a personal and professional one, as he grapples with the weight of the ongoing legal battles and the urgency of protecting the land he so deeply cares about.

Ramiro and Agustín

Ramiro and Agustín, both Ecuadorian constitutional judges, are crucial to the legal defense of Los Cedros. Their work in ensuring the forest’s protection within Ecuador’s “Rights of Nature” framework is a testament to their commitment to ecological justice.

Over the years, they have worked tirelessly through legal channels to challenge mining concessions that threatened to destroy the forest. Their expertise in constitutional law intersects with their passion for environmental justice, as they fight to extend the legal recognition of nature’s personhood.

Their ultimate victory in 2021, which declared mining in Los Cedros a violation of the Rights of Nature, marked a significant triumph for both the legal movement and the environmental cause they represent.

Josef DeCoux

Josef DeCoux, an American who has lived in Los Cedros for decades, represents the deep, personal connection one can form with the land. His rugged, solitary life in the forest is marked by a dedication to its protection against external threats.

DeCoux is a figure of perseverance, having resisted mining and logging operations for years. His personal history is intertwined with the forest’s own, as he has spent much of his life protecting its delicate ecosystems.

His isolation speaks to the sacrifices made by individuals who stand as guardians of the land, often at great personal cost. His life and work symbolize the ongoing struggle of environmental defenders worldwide, reflecting both the challenges and rewards of living in harmony with the land.

Rita Mestokosho

Rita Mestokosho, an Innu activist and poet, brings a spiritual and cultural perspective to the journey. She represents a deep connection to the land and the river, offering the group valuable insights into how Indigenous communities view and protect natural ecosystems.

Rita’s reverence for the Mutehekau Shipu river extends beyond a recognition of its physical importance; she sees the river as a sacred, living being deserving of respect and protection. Her belief in the spiritual guardianship of the land and its rivers profoundly influences the narrator and the others on the journey.

Rita’s actions, such as her invitation to offer tobacco to the river as a gesture of gratitude, are reflective of the profound relationship Indigenous communities have with the natural world, where the land and water are seen as integral parts of the living fabric of existence.

Wayne Chambliss

Wayne Chambliss, the narrator’s friend, plays an important role in the journey to the Mutehekau Shipu river. A companion to the narrator, Wayne’s perspective on the journey provides a grounded, practical element to their expedition.

As they face physical challenges, such as navigating the demanding Lac Magpie, Wayne’s camaraderie and support become essential to the narrator’s personal transformation. His presence underscores the value of shared experiences in fostering deeper connections with both nature and fellow travelers.

Wayne’s role is less about having a direct influence on the environment itself and more about serving as a partner in the exploration and transformation that the journey represents.

Analysis of Themes

The Rights of Nature

The “Rights of Nature” is a revolutionary theme explored in Is a River Alive. This concept challenges the traditional view of nature as a mere collection of resources available for human use.

Instead, it advocates for the recognition of natural entities—rivers, forests, mountains, and other ecosystems—as living beings with inherent rights. The legal recognition of nature’s rights is an extension of this philosophy, seen in the groundbreaking movements in countries like Ecuador and New Zealand.

Ecuador’s 2008 constitutional recognition of nature’s rights was a pioneering move in acknowledging that ecosystems possess legal standing and should be protected as individuals, not merely as property. This development calls for a radical shift in how society views its relationship with the environment, urging that rivers, forests, and other natural systems are integral, living parts of the world and deserve legal protection from exploitation, just like humans.

The idea that a river, such as New Zealand’s Whanganui River, can be granted personhood and treated as an entity capable of having its own legal voice, challenges anthropocentric legal systems. The movement promotes the idea that nature is not only essential for human survival but also has intrinsic value that transcends human needs.

This legal shift is not just a matter of environmental conservation; it marks a philosophical transformation that calls for an overhaul of current legal frameworks, emphasizing a more harmonious and ethical relationship with the Earth.

The Interconnectedness of Life

The idea of interconnectedness forms another central theme throughout Is a River Alive. The narrative brings to light the profound relationships that exist among humans, rivers, and the broader ecosystem.

The journey of the river is symbolic of the life cycle of nature itself, illustrating how all life is interconnected. The narrative weaves together ancient civilizations’ reverence for rivers and the modern struggles to preserve them, emphasizing that rivers are not only physical entities but also spiritual and cultural symbols for communities.

The interconnectedness between human beings and rivers is especially poignant in the context of the Ecuadorian cloud forest of Los Cedros, where legal scholars and environmental activists use the Rights of Nature framework to preserve the sacred forest from mining. This theme extends beyond the physical realm to include the spiritual bond many cultures share with nature.

The Innu people’s connection to the Mutehekau Shipu River, seen as a sacred being, mirrors this profound relationship. Through their reverence for the river, the community underscores the concept that human life is intricately connected to the land, and thus the degradation of the environment results in the degradation of the community itself.

The theme of interconnectedness further explores the idea that human well-being is directly linked to the health of the natural world, and if nature suffers, so too do the people who depend on it.

Ecological Justice

Ecological justice, a theme woven through Is a River Alive, is fundamentally about recognizing the rights of ecosystems and the injustice faced by both nature and marginalized communities when the environment is exploited. This theme is particularly highlighted in the context of legal battles against mining in places like Los Cedros and the broader issues of deforestation and pollution.

Environmental degradation disproportionately affects Indigenous communities, whose cultures are deeply tied to the land. The legal victories in Ecuador, where mining concessions were overturned to protect natural ecosystems, represent a significant step in the fight for ecological justice.

These actions are not only legal victories but also cultural ones, as they acknowledge the intrinsic value of nature and the right of local communities to protect their ancestral lands. The theme is further explored through the concept of “slow violence,” which refers to the gradual and often unseen environmental harm caused by industries like mining, which can poison water sources, deplete resources, and permanently alter ecosystems.

By highlighting the struggles of communities in the Intag Valley and the efforts to stop resource extraction in sacred forests, the book underscores that ecological justice is not only about protecting nature but also about preserving cultural heritage and human rights. Ecological justice is framed as a moral imperative that transcends borders and legal systems, advocating for a global recognition of the rights of ecosystems to exist and thrive.

The Spiritual and Sacred Nature of the Environment

Another significant theme in Is a River Alive is the spiritual and sacred nature of the environment. Throughout the narrative, nature is portrayed not only as a physical entity but as something deeply spiritual and worthy of reverence.

This theme is explored through both the personal experiences of the author and the cultural practices of Indigenous peoples. The river, for example, is not simply a source of water but a living, breathing entity that holds deep significance in various spiritual and cultural traditions.

This reverence for nature is not a modern concept but one that stretches back through history, as seen in the practices of ancient civilizations and Indigenous groups. The Innu people’s view of the Mutehekau Shipu River as a sacred being underscores this belief, as does the idea of Pachamama in Andean cosmology, where the Earth is revered as a deity.

The narrative stresses that this spiritual connection to nature is not just about respect but also about the responsibility to protect it. The environmentalist movements and legal frameworks that challenge human exploitation of nature are rooted in this idea that nature is sacred and deserving of protection.

By portraying nature as a living, conscious being, the narrative invites readers to rethink their own relationship with the environment and to understand that protecting it is not just an ecological or economic necessity but a spiritual and moral obligation.

Human Responsibility and Environmental Stewardship

The theme of human responsibility and environmental stewardship is deeply embedded in Is a River Alive, especially as it explores the consequences of neglecting the natural world. The narrative examines how the growing demands of modern civilization—urbanization, industrialization, and the exploitation of natural resources—have led to the degradation of the environment.

The changing landscape, from sacred rivers and forests to polluted and overexploited resources, reflects the lack of respect and stewardship humans have shown toward nature. The story of the river, from its birth as a spring to its role in sustaining civilizations, underscores the vital importance of water and ecosystems in maintaining life.

The personal reflections of the author and the group of activists in the forest emphasize the collective responsibility humanity bears to preserve the health of natural systems for future generations. As legal frameworks like the Rights of Nature movement gain traction, the narrative calls for a renewed commitment to environmental stewardship, urging individuals and societies to protect and restore ecosystems.

This stewardship goes beyond conservation efforts—it requires a fundamental shift in how humans relate to the Earth, recognizing that human actions have far-reaching consequences and that true progress lies in harmony with the natural world. Through this theme, the narrative stresses that environmental protection is not a peripheral issue but central to the survival and flourishing of life itself.