Isola by Allegra Goodman Summary, Characters and Themes

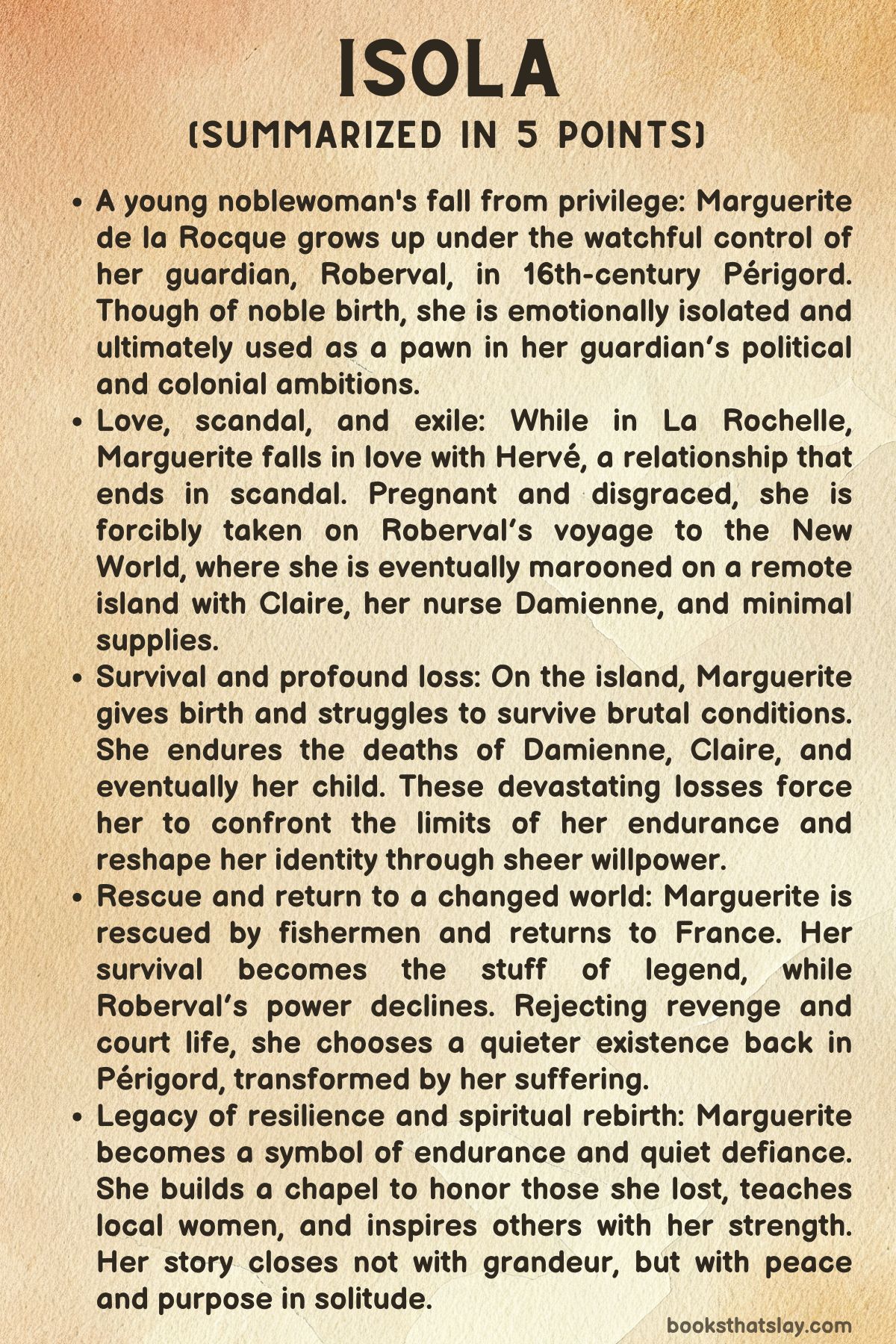

Isola by Allegra Goodman is a harrowing and lyrical historical novel that reimagines the true story of Marguerite de la Rocque, a 16th-century French noblewoman exiled to a remote island in the New World.

Set against the backdrop of Renaissance France and the brutal world of early colonization, the novel is both a survival epic and a profound spiritual journey. Goodman weaves together themes of patriarchal oppression, forbidden love, resilience, and redemption, transforming history into a deeply intimate portrait of a woman who loses everything and becomes stronger for it. It’s a haunting meditation on solitude, agency, and faith.

Summary

Isola follows the journey of Marguerite de la Rocque, a young French noblewoman whose life is irrevocably changed by betrayal, exile, and survival.

The novel opens in Périgord in 1531, where Marguerite is orphaned and raised in a château under the guardianship of her uncle, Jean-François de Roberval, a rigid and ambitious royal courtier. Though born into wealth, Marguerite grows up in emotional isolation, raised primarily by her nurse, Damienne.

Her life takes a turn when she meets Claire d’Artois, a gentle and scholarly girl, and her mother, Madame D’Artois. Under their guidance, Marguerite begins to mature intellectually and emotionally, forming bonds that prove critical to her later survival.

As Roberval returns to Périgord, financial decline sets in, and Marguerite’s place in society becomes more fragile. He mortgages the estate, displaces the women, and views Marguerite increasingly as a pawn for political gain.

Despite fears of being forced into marriage, Marguerite negotiates with Roberval and gains temporary reprieve, showing early signs of the agency and resilience that will define her later.

By 1539, Roberval moves his household to La Rochelle, a bustling port city rife with court intrigue and preparation for New World colonization. Marguerite struggles to adapt to the public scrutiny and elite expectations of city life.

There, she meets Hervé, a charming young man who ignites in her a passionate, secret romance. Their bond grows, offering her a sense of freedom and self-worth—but it also places her in grave danger.

Claire warns her of the consequences of secrecy and desire, but Marguerite ignores the risks. When her pregnancy becomes harder to conceal, Roberval’s control tightens, and scandal looms.

In 1542, Roberval, now authorized to lead a colonizing expedition to New France, forces Marguerite, Claire, and Damienne to join his voyage.

The sea crossing is brutal, marked by storm, surveillance, and the slow unraveling of Marguerite’s hopes. Roberval, learning of her pregnancy, sees her as a disgrace and an obstacle to his ambitions. Upon reaching an uninhabited island, he maroons Marguerite, Claire, and Damienne, providing minimal supplies under the guise of divine punishment.

Stranded and vulnerable, the women rely on each other to survive. Marguerite gives birth to a daughter in dire conditions.

The child becomes a symbol of love and resistance, but the island’s harshness claims Damienne and then Claire. Marguerite, now alone with her baby, learns to adapt to the wilderness, creating tools, foraging, and building shelter. Tragedy strikes again when her infant falls ill and dies. Grief nearly destroys her, but Marguerite chooses to live.

She begins to name the landscape, mark time, and craft meaning from her suffering. Her exile becomes a crucible in which she is spiritually transformed.

In 1544, a Basque fishing crew discovers her alive. Emaciated but dignified, Marguerite returns to France, where her survival causes a stir. She refuses to return to court life or seek vengeance on Roberval, whose reputation has already begun to crumble. Instead, she returns to Périgord with Madame D’Artois and reclaims a modest portion of her childhood estate.

There, she builds a chapel in memory of Damienne, Claire, and her daughter, offering sanctuary to other women. Her legend grows, but Marguerite remains grounded and solitary, a woman who endured abandonment and death yet emerged with quiet strength and a profound sense of purpose.

The novel ends with Marguerite walking alone through the fields of Périgord, her journey complete—not in triumph, but in hard-won peace. Her story becomes one of myth, not for what she lost, but for how she endured.

Characters

Marguerite de la Rocque

Marguerite de la Rocque is the central figure in Isola by Allegra Goodman. She starts as an orphaned noblewoman, experiencing deep emotional isolation despite her aristocratic status.

As the narrative unfolds, Marguerite’s journey from privileged but powerless daughter to a survivor of exile is profound. In her early years, Marguerite struggles with her lack of agency, living under the control of her guardian, Jean-François de la Rocque de Roberval.

She harbors a longing for love and identity, and her relationship with Claire d’Artois serves as a source of emotional connection and growth. However, her life begins to change drastically as she moves to La Rochelle and is exposed to the challenges of court politics, love, and betrayal.

When she is exiled to an island, Marguerite transforms from a noblewoman into a self-sufficient survivor, enduring hardships that strip away her previous identity. Her strength deepens as she faces the death of those she loves, ultimately emerging as a spiritual figure for others.

Her resilience, resourcefulness, and transformation throughout the novel reflect her growth from helplessness to empowerment.

Jean-François de la Rocque de Roberval

Roberval is Marguerite’s guardian and the man who ultimately condemns her to exile. He embodies the stern and controlling patriarchal figure of the time.

Initially, he is distant and cold, focusing on his own ambitions rather than Marguerite’s well-being. As the narrative progresses, his character is revealed to be driven by a desire for wealth, power, and colonial conquest.

He takes advantage of Marguerite’s status as his ward, using her to solidify his political and financial goals. His decision to maroon her on a desolate island symbolizes his utter lack of compassion and the extent to which he views her not as a niece or a person, but as a tool for his own purposes.

Roberval’s harsh treatment of Marguerite, his exploitation of her vulnerability, and his eventual disfavor among the royal court reflect his moral and personal decline. Ultimately, Roberval’s character arc shows him as a tragic figure whose pride and ambition lead to his downfall.

Claire d’Artois

Claire d’Artois plays a pivotal role in Marguerite’s emotional development. She is a companion and confidante who offers Marguerite both friendship and spiritual guidance.

Their relationship is marked by a contrast between Marguerite’s impetuousness and Claire’s grace and calmness. Claire is portrayed as a grounded and humble character, someone who has been raised with a sense of dignity and wisdom, which Marguerite initially envies.

However, as their friendship deepens, Claire becomes more than just a friend; she represents the ideals of virtue and spiritual strength. Claire’s warnings to Marguerite about her romantic involvement with Hervé highlight her role as a voice of reason, even if Marguerite does not always heed her advice.

Her eventual death on the island is a turning point for Marguerite, deepening her sense of loss and highlighting the fragility of the bonds they shared. Claire’s influence on Marguerite remains strong even after her death, symbolizing the importance of friendship, moral grounding, and spiritual clarity.

Damienne

Damienne, Marguerite’s nurse and surrogate mother, is a figure of unwavering loyalty and devotion. She represents the maternal love and protection that Marguerite lacks from her biological mother, who died when Marguerite was born.

Damienne’s presence in the novel serves as a constant source of emotional stability for Marguerite, especially in the early parts of the story when the young girl feels lost and alone. Damienne’s death on the island marks the end of Marguerite’s childhood and the start of her transformation into a solitary adult.

Though her role is secondary to Marguerite’s, Damienne’s maternal influence is crucial in shaping Marguerite’s sense of duty, compassion, and survival instincts. The emotional weight of Damienne’s loss further isolates Marguerite, but also strengthens her resolve to survive, illustrating the profound impact Damienne had on her life.

Hervé

Hervé is a young, charismatic man with whom Marguerite embarks on a secret romance. He is depicted as ambitious and full of promise, offering Marguerite the possibility of love and escape from her otherwise controlled and isolated existence.

Hervé’s relationship with Marguerite serves as a form of emotional liberation for her, providing her with a sense of self-worth and desire. However, their secret affair also highlights the tension between Marguerite’s internal desires and the external pressures placed on her by Roberval.

His disappearance, presumed to be a result of Roberval’s wrath, marks a tragic turning point in the novel. His loss devastates Marguerite, further compounding her sense of abandonment and loss.

Although Hervé’s character is not as deeply explored as some others, his role in Marguerite’s life represents the fleeting nature of love and the consequences of defying societal constraints.

Themes

Gender and Patriarchy in 16th Century France

The novel Isola explores the theme of gender and the restrictive norms surrounding women in 16th-century France. Marguerite’s journey from childhood to womanhood is framed within a patriarchal society where women, regardless of their noble birth, have little autonomy.

In the first part of the book, Marguerite’s guardian, Roberval, controls her life, keeping her in a state of dependency and denying her the agency she seeks. As she matures, Marguerite begins to understand the full extent of her powerlessness within a system that values her primarily for her marital prospects rather than her individual identity.

The novel highlights the limited roles available to women, who are often treated as objects of exchange or pawns in political and social negotiations, as exemplified by Roberval’s decision to marry her off. Even when she tries to assert herself by forming a romantic relationship with Hervé, this act of defiance leads to her being punished and marooned.

The novel underscores how gender shapes Marguerite’s life choices, limiting her options and defining her worth based on her relationships with men, whether as a daughter, a potential wife, or a mother.

Colonialism and the Exploitation of Land and People

The theme of colonialism is also central to Isola, particularly as it intertwines with Roberval’s ambitions for power, wealth, and glory. Roberval’s expedition to New France is not merely about exploration but about asserting dominance over new territories for economic and political gain.

Marguerite’s role in this colonial venture is symbolic; she is not just a passive observer of history but a participant whose fate becomes intertwined with Roberval’s imperialist project. Her journey to the New World is framed within the broader context of European colonialism, where individuals like Roberval seek to exploit the land and people of the Americas in the name of progress and civilization.

In this context, Marguerite’s exile can be seen as a personal and literal manifestation of the violence and dispossession that colonial expansion brings—loss of agency, forced dislocation, and the destruction of personal identity. While Roberval sees his venture as an opportunity for personal advancement, Marguerite’s experience reflects the devastating human costs of colonial exploitation.

As Marguerite is cast away to an island with little regard for her survival, it becomes evident that the colonial project is rooted in the dehumanization of those who are seen as expendable.

Spiritual Transformation and the Search for Meaning in Isolation

One of the most compelling themes in Isola is the idea of spiritual transformation that Marguerite undergoes in her physical and emotional isolation. After being marooned on a desolate island, Marguerite is cut off from the structures of power and society that once defined her.

In her exile, she faces immense physical challenges—hunger, cold, and the death of her companions—but these hardships also serve as a crucible for spiritual growth. Through her intense suffering, Marguerite begins to embrace a new sense of self, detached from the external validation she once sought.

The narrative emphasizes that her transformation is not simply about surviving but about finding deeper meaning in the face of profound loss. Her relationship with God and the natural world becomes central to her survival, as she engages in prayer and meditation to find solace and purpose.

Marguerite’s shift from being a noblewoman concerned with societal expectations to a woman focused on inner strength and spiritual clarity symbolizes a journey of personal transcendence. She learns to confront her grief and pain, ultimately finding peace in her solitude, and her spiritual awakening marks her as both a survivor and a figure of wisdom.

In this light, Marguerite’s evolution into a spiritual matriarch at the end of the novel illustrates the power of inner transformation, even in the most dire of circumstances.

Human Connection and the Costs of Survival

Another significant theme in Isola is the fragility of human connection and the emotional and psychological toll of survival. Throughout her time on the island, Marguerite experiences profound isolation, both physically and emotionally.

Her relationships with Claire, Damienne, and her daughter are central to her sense of self, and their deaths mark the ultimate loss for Marguerite. The brutal conditions of the island force her to reckon with the transience of life and the inevitable solitude that follows.

The struggle to stay alive can often come at the expense of emotional attachment, as survival requires Marguerite to harden herself against the grief and loss that come with it. However, Marguerite’s ability to rebuild after these losses suggests that while human connections are fragile, they are also essential for resilience.

Her eventual transformation into a figure who fosters strength and guidance for others shows that survival does not simply mean physical endurance—it involves emotional fortitude and the capacity to continue caring for others, even in the face of overwhelming hardship.

The Power of Memory and Legacy in the Face of Adversity

Finally, Isola explores the theme of memory and legacy, particularly how individuals seek to shape their own narratives in the face of adversity. Marguerite’s exile and her eventual survival in the wilderness leave her with little hope of traditional legacy—no titles, no wealth, and no public recognition.

Yet, she finds a way to create a legacy that transcends her immediate circumstances. By the end of the novel, Marguerite has transformed the isolated island into a site of spiritual significance, building a chapel and offering guidance to other women.

In doing so, she reclaims agency and defines her own legacy, not through material success or social standing, but through the emotional and spiritual connections she fosters with others. This theme also extends to the way Marguerite reflects on her past life in Périgord—her memories of childhood, of Claire, of Damienne, and her daughter, all shape her understanding of her identity.

By remembering and honoring those she loved and lost, Marguerite ensures that their stories live on, even if only in quiet moments of reflection. In this sense, the novel suggests that while historical events may often erase individuals from collective memory, personal legacies can endure through acts of remembrance, love, and the quiet strength to endure.