Katabasis by R.F.Kuang Summary, Characters and Themes

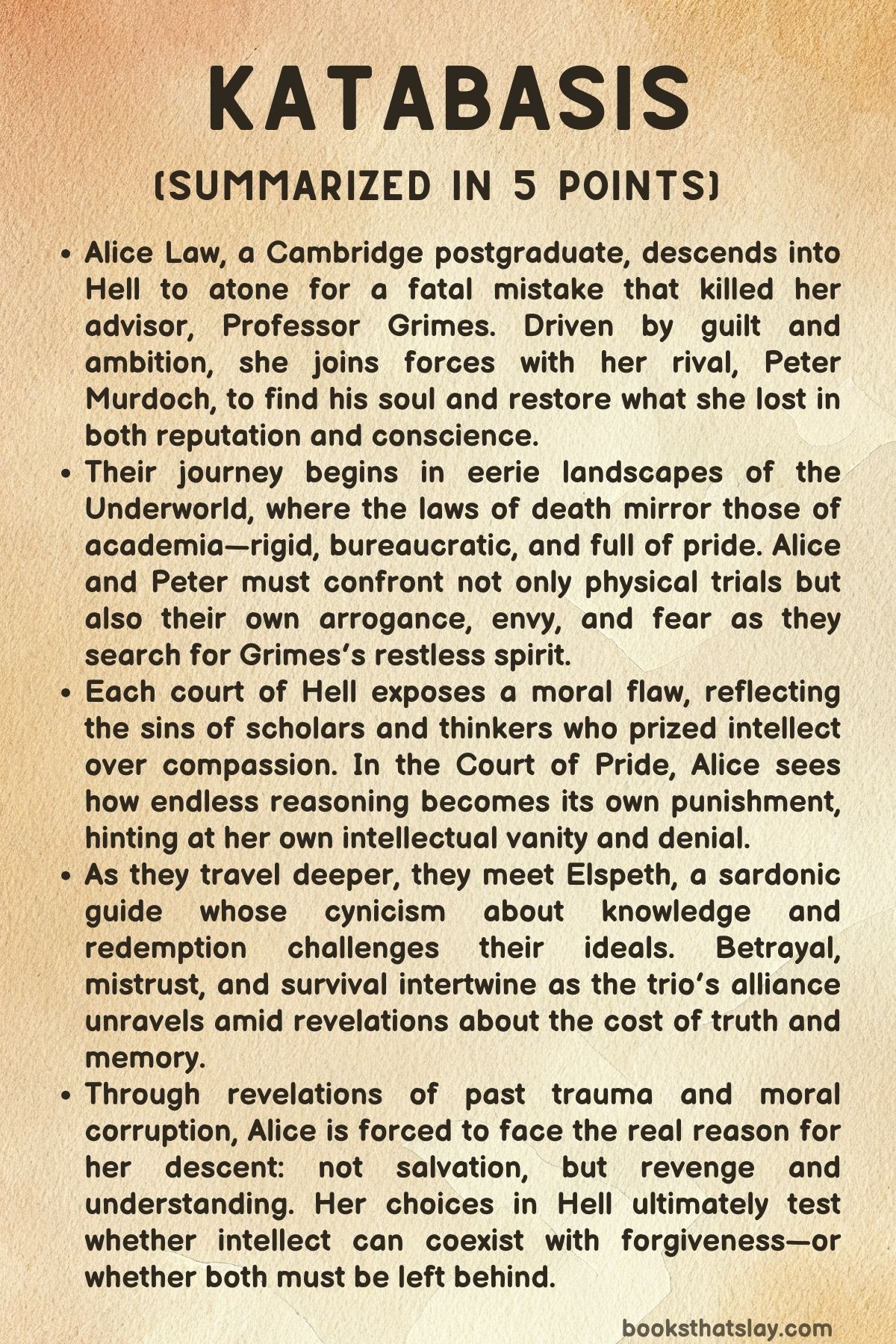

Katabasis by R.F. Kuang is a dark and imaginative exploration of guilt, ambition, and moral decay within the academic world, filtered through a mythic descent into the underworld. Set in an alternate Cambridge where magic and philosophy intertwine, the novel follows Alice Law, a brilliant yet tormented postgraduate student who ventures into Hell to retrieve her deceased mentor’s soul.

What begins as an academic quest soon becomes a confrontation with her own trauma, complicity, and desire for power. Through this infernal journey, Kuang exposes how obsession, pride, and the hunger for intellectual immortality can become their own form of damnation.

Summary

Alice Law, a postgraduate at Cambridge’s Department of Analytic Magick, is haunted by guilt over the death of her mentor, Professor Jacob Grimes. His demise in a failed magical experiment was her fault—she neglected to seal a pentagram’s loop, triggering a violent rupture that killed him instantly.

To protect herself, Alice concealed all evidence of her involvement. Still, guilt festers, and desperation drives her to attempt a dangerous resurrection.

Without Grimes, she cannot finish her dissertation or secure her academic future. Her research into Tartarology, the study of the underworld, culminates in a forbidden spell designed to reach Hell and bring him back.

Just as Alice prepares the incantation, Peter Murdoch—her rival and fellow student—interrupts. Peter, disheveled yet brilliant, insists on joining her, revealing he has also studied underworld traversal.

With no time to argue, Alice agrees. Together, they sacrifice half their remaining lifespans to fuel the spell.

The earth trembles, light engulfs them, and they awaken in Hell’s bleak gray plains under a red sky.

Their journey begins in eerie calm beneath the “Viewing Pavilion,” a place where the living and dead faintly perceive each other. Alice mischievously tries to contact the living world but is reminded by Peter that escaping Hell requires the permission of Lord Yama, ruler of the underworld.

As they move forward, they encounter the Fields of Asphodel, filled with lost souls wandering endlessly. Hoping to find Grimes, they summon the dead through a ritual offering, but instead are visited by Shades—students who died decades earlier under Grimes’s supervision.

Bitter and mutilated, they reveal that Grimes passed through recently, still arrogant in death. Terrified of reincarnation, they prefer eternal stagnation to losing their intellects.

The encounter leaves Alice disturbed but determined.

Following their lead, Alice and Peter reach an immense white wall stretching across the horizon, where Shades queue for reincarnation. When they attempt to cut ahead, the spirits attack, forcing them to retreat.

Learning Grimes has already passed through, they decide to climb the wall—constructed from compacted bones. Alice leads; Peter, terrified of heights, falters, but she helps him push through.

At the summit, they glimpse Hell’s vast, shifting landscape: a chaotic realm that refuses fixed shape, morphing between deserts, seas, and labyrinths. It is both awe-inspiring and disorienting.

Descending into the next level, they camp and confront their mutual resentments. Old academic rivalries resurface—Peter’s success in winning the Cooke Fellowship, Alice’s humiliation, and their shared resentment toward Grimes’s manipulative mentorship.

The night’s awkward intimacy softens their hostility briefly. The next day, Hell reshapes itself into a grotesque reflection of Cambridge: Gothic towers, courtyards, and libraries, devoid of life.

They realize they have entered the Court of Pride, a domain punishing scholars consumed by vanity.

Inside the court’s grand library, they meet Moore, a Shade and self-appointed dean, who explains that all trapped souls must define “the good” to advance. Endless debates rage among Shades obsessed with logic and philosophy, each punished by their own intellectual arrogance.

When Moore grows threatening, Alice distracts him with a logical paradox that traps him in infinite reasoning, allowing their escape. Outside, they encounter the River Lethe—its dark waters shimmering with fragments of memory.

Peter speculates that the river connects all courts, but its waters are lethal to the mind. The two move onward along its banks.

Their path crosses with Elspeth, a mysterious ferryman who offers passage across the Lethe. As they sail, Elspeth teaches them about the river’s nature: it absorbs every forgotten memory yet never destroys them.

They witness flickering visions of lost lives within the current. When a monstrous, many-eyed nightmare surfaces, Elspeth repels it, revealing her deep knowledge of Hell’s creatures.

Her cynicism about human memory and pain fascinates Alice, who begins to envy the peace of forgetting. They reach the shore of Greed, a desert where souls fight endlessly over worthless trinkets.

The cruelty of human ambition repeats itself even in death.

Moving onward to Wrath, the group splits when Elspeth leaves to gather embers from a fiery deity’s footprints. Peter and Alice conspire to trap her using a pentagram, but their plan backfires when Elspeth’s cat exposes it.

Enraged by betrayal, Elspeth transforms into a storm of butterflies and casts them from her boat into the wasteland. Stranded and furious, Alice and Peter argue bitterly until Alice confesses the truth: Grimes’s death was her fault.

The admission leads her to recount her harrowing past—Grimes’s predation, the sexism of academia, and her own moral compromises. He had harassed her and others, destroyed her reputation, and left her isolated.

His death had freed her, and her descent into Hell was both penance and defiance.

Peter listens in stunned silence. When he asks what she truly intended, Alice admits she never meant to resurrect Grimes as a living man.

Instead, she sought to bind his soul to his corpse—forcing him to speak, to serve her, and to suffer. Her goal was not redemption but control.

Peter, shaken yet strangely admiring, calls her plan “fascinating. ” They share a fragile understanding amid the chaos.

Later, Alice performs another necromantic act, binding the soul of Nick Kripke into a corpse, unleashing agony that fractures the very structure of Hell. Amid violent distortions, the landscape shifts to the banks of the Lethe, where Alice drags Nick’s tormented form toward the water.

As he disintegrates, other souls—including Magnolia and her son—walk willingly into the river, seeking release through oblivion. One by one, memories dissolve into the current.

Exhausted and half-mad, Alice nearly succumbs to Lethe’s pull, but Elspeth reappears, rescuing her. Together aboard the Neurath, they share a quiet reconciliation.

Alice’s protective sigils, once carved into her skin, fade as Lethe’s water burns away her knowledge. Elspeth offers comfort and gives Alice the Dialetheia—a rare plant embodying contradiction, capable of granting a divine boon.

It is both gift and test.

They reach Yama’s domain, an island where geometry folds and souls are judged. Alice bargains with Yama, offering the Dialetheia in exchange for an audience with Grimes.

His Shade appears, charming and manipulative, urging Alice to stay in Hell and exploit its infinite potential. For the first time, she sees through him.

Calmly, she performs a final ritual that destroys his soul completely. Yama, intrigued, honors her courage and releases Peter, alive but scarred, from the void.

Together, Alice and Peter present the Dialetheia, asking for restored lifespans and a return to the world. Yama grants half their years back and opens a spiral stair leading upward.

They ascend through fading landscapes of Hell until they reach a trapdoor rimmed with butterflies. Stepping through, they emerge beneath the night sky of Cambridge.

The underworld fades behind them. Hand in hand, they walk toward a new life—scarred, changed, but free.

Characters

Alice Law

Alice Law stands as the emotional and moral center of Katabasis. A postgraduate student at Cambridge’s Department of Analytic Magick, she begins her journey burdened by guilt, ambition, and trauma.

Her descent into Hell mirrors her internal descent—a quest not just for redemption but for understanding and reclaiming agency in a world that has persistently denied it to her. Alice’s intellect and obsession with control initially appear as virtues, but they are revealed to be shields against her self-loathing and the patriarchal violence she endured under Professor Grimes.

Her actions, from concealing her culpability in his death to orchestrating a forbidden descent into the underworld, reflect a complicated blend of arrogance, desperation, and the longing to make meaning out of suffering.

Throughout the narrative, Alice evolves from a guilt-ridden scholar defined by external validation to a woman who recognizes the futility of academic and moral hierarchies. Her confrontation with Grimes in the underworld marks a pivotal catharsis—she rejects his manipulative power, dismantling the very authority that once consumed her.

The final act, in which she and Peter emerge from Hell reborn, symbolizes her reclamation of autonomy and her acceptance of imperfection. Alice’s journey is thus both literal and metaphysical—a resurrection of selfhood forged in defiance of intellectual and emotional tyranny.

Peter Murdoch

Peter Murdoch, Alice’s rival and reluctant companion, embodies the duality of intellect and insecurity that defines much of Katabasis’s academic critique. A gifted but fragile scholar, Peter’s brilliance is undermined by envy and a yearning for validation.

His relationship with Alice oscillates between camaraderie, competition, and resentment, mirroring the toxic dynamics that pervade their academic environment. Unlike Alice, Peter’s pride manifests in moral cowardice and self-deception—he often cloaks his fear in reason, refusing to confront his complicity in the system that destroyed them both.

As the narrative unfolds, Peter’s descent into Hell becomes a crucible for empathy and courage. His physical fears, such as his terror of climbing the bone wall, parallel his psychological paralysis in confronting the truth about Grimes and himself.

Yet by the end, Peter demonstrates emotional growth—he listens to Alice’s confession without judgment, offering solidarity rather than superiority. His eventual death and resurrection alongside Alice symbolize his transformation from a self-serving intellectual to a partner capable of emotional integrity.

Peter is both mirror and foil to Alice—his redemption reinforces hers, grounding the novel’s exploration of shared guilt and fragile humanity.

Professor Jacob Grimes

Professor Jacob Grimes, though dead at the novel’s start, casts a long and suffocating shadow over Katabasis. As a mentor, he embodies the corruption of academic authority—a figure of genius and abuse who manipulates his students intellectually, emotionally, and sexually.

Grimes represents the seductive cruelty of power disguised as intellect; his charisma masks his predation, and his death fails to extinguish his influence. In Hell, he is revealed as unchanged—still arrogant, manipulative, and utterly convinced of his superiority.

His efforts to persuade Alice to join him in exploiting the Dialetheia expose the hollowness of his scholarship, rooted in domination rather than discovery.

Grimes functions as both antagonist and symbol: he personifies the patriarchal system that commodifies brilliance while crushing vulnerability. Alice’s final act of annihilating him is therefore not merely vengeance but liberation—a rejection of the academic and moral structures that once enslaved her mind.

Through Grimes, the novel dissects the myth of the “great man” scholar, exposing the violence that sustains intellectual prestige.

Elspeth

Elspeth, the mysterious ferryman of the Lethe, emerges as one of the novel’s most enigmatic and compelling figures. A blend of guide, skeptic, and mirror, she embodies the wisdom of disillusionment.

Her cynicism toward academia—calling it vain, futile, and self-destructive—contrasts sharply with Alice and Peter’s naive idealism. Yet beneath her bitterness lies compassion and clarity; she sees through illusions, understanding that Hell reflects one’s inner nature rather than divine judgment.

Her relationship with Alice evolves from wary mentorship to genuine empathy, culminating in her final gift of the Dialetheia—a symbol of faith and contradiction.

Elspeth’s philosophy—that Hell is reflection, not punishment—becomes a thematic cornerstone of Katabasis. She bridges the gap between damnation and enlightenment, revealing that salvation lies not in escape but in acceptance.

Her decision to remain in Hell, content with her fate, contrasts with Alice’s return to the world, underscoring the novel’s meditation on choice, identity, and peace.

Nicomachus (Nick) Kripke

Nick Kripke serves as both a cautionary figure and a tragic emblem of intellectual obsession. His resurrection by Alice is one of the novel’s most disturbing moments—an act of cruelty masquerading as control.

Once a scholar who sought transcendence through knowledge, Nick becomes a grotesque reflection of the magicians’ hubris, his tortured reanimation demonstrating the cost of manipulating life and death. His dissolution into the Lethe marks a grim form of release; he achieves the oblivion that scholars like Grimes and Alice have feared and resisted.

Through Nick, Katabasis explores the perils of unbounded curiosity and the moral decay that accompanies the pursuit of mastery. He embodies the self-consuming drive of the intellect when divorced from empathy, his fate a warning that even brilliance cannot withstand the erosion of the soul.

King Yama

King Yama, the Lord of Death, serves as both judge and cosmic balance within the structure of Katabasis. His presence is neither punitive nor benevolent; he embodies neutrality—the acceptance of contradiction, the inevitability of consequence.

When Alice presents the Dialetheia, Yama’s amusement and measured grace reveal a divine perspective beyond human moral binaries. His restoration of half their lifespans and his absorption of the Dialetheia’s light symbolize equilibrium rather than mercy—a return to order after chaos.

Yama’s throne room, where souls pass through the arch at his touch, encapsulates the novel’s central paradox: death as both ending and renewal. In his hands, justice becomes reconciliation rather than retribution.

Through Yama, the narrative closes its philosophical circle—affirming that knowledge, guilt, and love must coexist in their contradictions, and that true wisdom lies in accepting what cannot be undone.

Themes

Guilt and Redemption

From its opening pages, Katabasis positions guilt as both Alice’s punishment and her propulsion. The novel turns her descent into Hell into a psychological reckoning rather than a mere supernatural adventure.

Alice’s guilt begins with Professor Grimes’s death—a consequence of her own failure—and evolves into something far deeper: the recognition that her complicity extended long before the accident. Her silence during Grimes’s years of exploitation, her self-deception about his abuse, and her willingness to destroy evidence after his death all form layers of a burden that no spell can lift.

Each encounter in Hell externalizes this guilt: the Shades who refuse reincarnation mirror her own fear of accountability; the endless courts expose her inability to move on. Redemption, in this context, becomes inseparable from acknowledgment.

Alice’s attempt to resurrect Grimes is not born of compassion but of self-preservation, a need to rewrite her own narrative. Yet her journey transforms this impulse into confrontation—she comes to see that true redemption does not lie in reversing the past but in naming it.

Her eventual rejection of Grimes before King Yama is the culmination of this arc. The act is neither dramatic nor sentimental; it is a quiet assertion of moral clarity.

By binding Grimes’s soul to oblivion, Alice accepts her own culpability while reclaiming power over her trauma. Redemption here is not absolution from sin but liberation from silence, a reclamation of identity after years of intellectual and emotional bondage.

Power, Knowledge, and Corruption

The world of Katabasis treats academia as a mirror of Hell itself—a hierarchy where intellect masquerades as virtue but often conceals vanity and cruelty. R.

F. Kuang constructs Cambridge and the Courts of Hell as parallel institutions, each obsessed with defining “the good” while perpetuating injustice.

In the Court of Pride, scholars are condemned to debate ethics endlessly, their brilliance turned into self-parody. This punishment reveals the central irony of the novel: knowledge pursued without humility becomes a form of damnation.

Alice, Grimes, Peter, and Elspeth are all products of this intellectual system that prizes mastery over understanding. Grimes’s genius is weaponized to manipulate others; Peter’s curiosity verges on recklessness; Elspeth’s cynicism curdles into nihilism; and Alice’s own brilliance becomes a cage of perfectionism and shame.

Kuang shows how knowledge, when stripped of empathy, breeds moral decay. The magical system of the novel—a precise blend of ritual and reason—symbolizes this duality.

Every spell requires sacrifice; every act of knowing consumes life itself. By the end, Alice recognizes that wisdom lies not in domination or cleverness but in relinquishing control.

Her destruction of Grimes is therefore an epistemological act: she denies the authority of corrupt knowledge and asserts a new ethic grounded in survival, not superiority. The journey through Hell becomes an allegory for academia’s descent into hubris, exposing how institutions built on enlightenment can replicate the very darkness they claim to dispel.

Feminine Agency and Resistance

Beneath its metaphysical structure, Katabasis is fundamentally a story about a woman reclaiming agency in a system designed to erase it. Alice’s arc traces the long, painful emergence of self-possession after years of coercion and misogyny.

Her relationship with Grimes encapsulates the gendered dynamics of power that dominate academic spaces—the mentor who uses authority as entitlement, the institution that protects the abuser, and the culture that shames the victim into silence. Alice’s early complicity—her belief that proximity to Grimes’s intellect could shield her from vulnerability—reflects the internalized logic of patriarchal academia.

Her descent into Hell literalizes her psychological entrapment: she must traverse a world ruled by male hierarchies, from the philosophers of Pride to the lordly Yama himself, before she can speak in her own voice. Kuang portrays her rebellion not as sudden vengeance but as a process of unlearning obedience.

When Alice confesses her past to Peter, it is the first time her story exists outside Grimes’s shadow. By confronting Grimes in the final act, she transforms the victim’s silence into the survivor’s command.

Destroying him is not merely revenge—it is a declaration that her mind, body, and future are her own. Feminine agency in the novel thus emerges through defiance and reconstruction: Alice claims not only her voice but the right to define the terms of her resurrection, rejecting the narrative written for her by men and gods alike.

Memory, Forgetting, and Identity

The River Lethe stands at the philosophical heart of Katabasis, embodying the tension between remembering and forgetting that governs every soul’s journey. Kuang transforms the classical symbol of oblivion into a metaphor for trauma and survival.

Memory in the novel is both torment and tether—what keeps Alice human and what threatens to destroy her. The Lethe’s promise of erasure tempts her throughout the narrative, especially after the confessions that expose her pain.

Elspeth’s tales of the Kripkes—souls who drink the river to dull their anguish—mirror the human desire to escape consciousness itself. Yet the novel insists that identity cannot exist without the continuity of memory.

When Alice’s tattoos begin to dissolve in the Lethe, she experiences a terror more profound than death: the loss of the very language that defines her. Forgetting, once imagined as mercy, becomes annihilation.

The journey toward King Yama thus becomes an argument against oblivion. To live again, Alice must remember—not perfectly, but enough to hold meaning.

Her survival depends on a selective preservation of self: she accepts the past but refuses to be defined solely by it. Kuang’s portrayal of memory is not nostalgic but moral; it demands accountability even as it acknowledges pain.

In the end, the Lethe is not an endpoint but a threshold—a reminder that healing requires remembrance, and that identity, once erased, can only be rewritten through choice, not through forgetting.

Death, Rebirth, and Transformation

The structure of Katabasis follows the mythic rhythm of descent and return, but Kuang reshapes it into an existential meditation on transformation rather than salvation. Every stage of Hell strips Alice of illusions—her belief in intellectual purity, her rational defenses, her fantasies of control.

Death here is not punishment but revelation, exposing the falseness of the lives the characters built. The underworld is populated by scholars, magicians, and thinkers who refuse reincarnation because they fear mediocrity, an inversion of the human instinct to evolve.

Against this backdrop, Alice’s decision to seek rebirth marks an act of radical courage. Her final ascent through the courts, hand in hand with Peter, signifies more than physical return—it represents the acceptance of imperfection as the condition of life.

Rebirth, in this narrative, is not a restoration of the old self but the birth of a self reconciled with loss. By trading the Dialetheia for a second chance, Alice relinquishes omnipotence for the possibility of change.

The transformation is quiet yet absolute: she emerges not purified but human, stripped of certainty yet capable of love and forgiveness. Kuang’s vision of rebirth rejects transcendence in favor of continuity—it honors the broken, the guilty, and the striving as the true bearers of meaning.

Death, in Katabasis, is only the beginning of learning how to live.