Kiss Her Goodbye Summary, Characters and Themes | Lisa Gardner

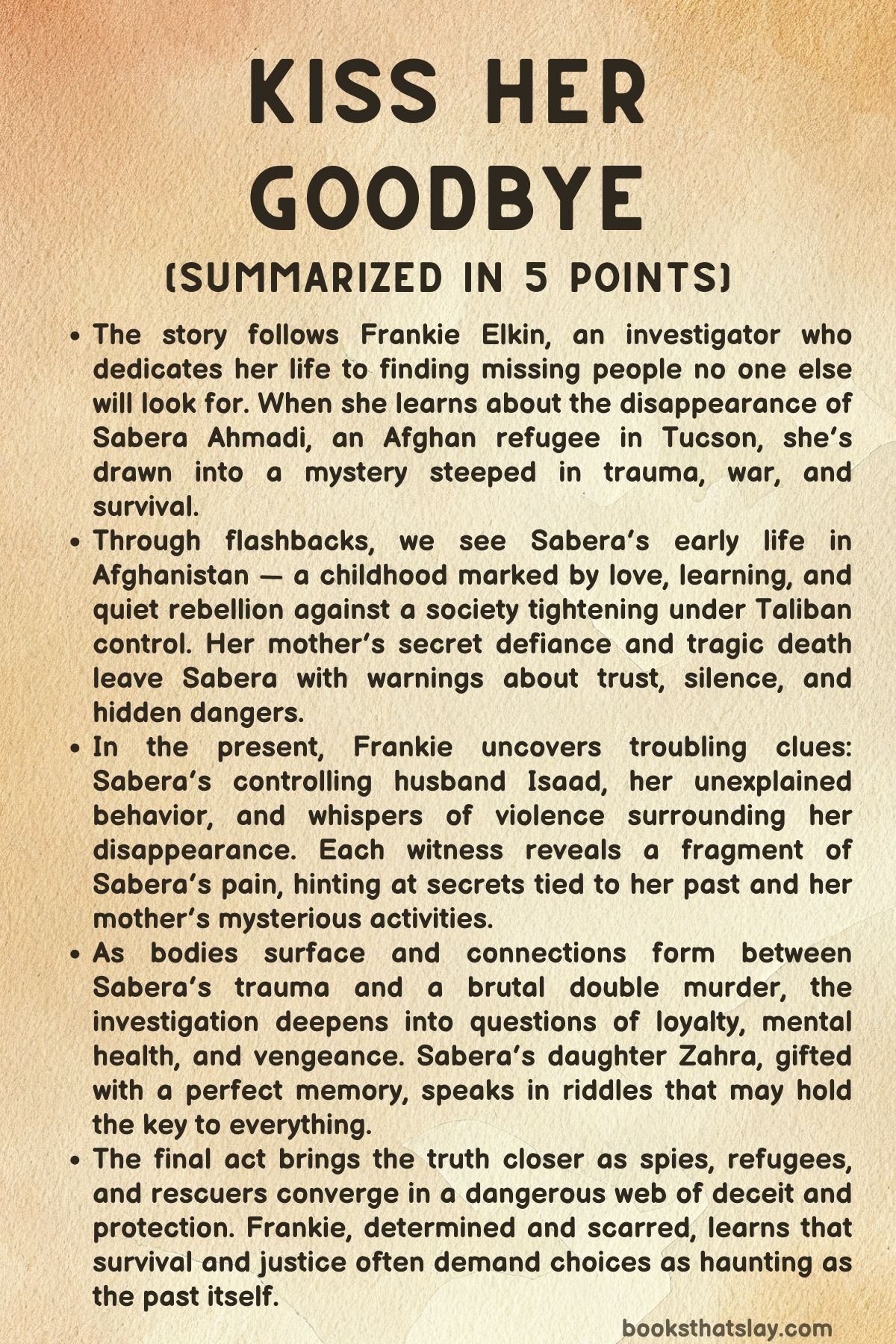

Kiss Her Goodbye by Lisa Gardner is a taut psychological thriller that explores trauma, resilience, and the haunting cost of survival. The novel follows Frankie Elkin, a wandering investigator who dedicates her life to finding missing people overlooked by others.

Her latest case involves Sabera Ahmadi, an Afghan refugee and mother who has vanished in Tucson, Arizona. As Frankie delves deeper, she uncovers layers of secrets spanning continents—from war-torn Kabul to America’s refugee communities. Through Sabera’s story, Gardner examines the enduring scars of conflict, the complexity of cultural displacement, and the lengths to which a mother will go to protect her child. It’s the 4th book in the Frankie Elkin series by the author.

Summary

The story begins in Afghanistan, where young Sabera Ahmadi grows up in a loving, educated household. Her father is a literature professor, her mother a bold fashion designer who secretly aids resistance movements, and her older brother Farshid is her closest companion.

Their home brims with warmth and books, even as war encroaches. When her mother falls mysteriously ill, Sabera is forced into premature adulthood.

On her deathbed, her mother entrusts her with cryptic advice—never trust her uncles, protect what she loves, and clean out the sewing room after her passing. Hidden among fabric and threads, Sabera discovers tokens of her mother’s secret life, revealing that she was part of a quiet rebellion against oppressive forces.

The political climate deteriorates swiftly as the Taliban reclaims Kabul. Herat and the family’s countryside refuge are no longer safe.

As violence spreads, Sabera’s father and brother attempt to shield their home but fall victim to brutal killings. Alone amid devastation, Sabera retrieves a few keepsakes and her brother’s rifle before fleeing into the chaos, clutching her mother’s words like a compass: “When I became a woman, I woke up.”

Years later, the narrative shifts to Arizona. Frankie Elkin, a self-taught investigator who searches for missing persons, is approached by Aliah, an Afghan refugee who pleads for help finding her friend Sabera.

Police dismiss the case, but Aliah insists Sabera would never abandon her young daughter, Zahra. Frankie, haunted by her own loneliness and addiction, accepts.

She finds a temporary home as a pet-sitter for an eccentric man, Bart, whose mansion is filled with reptiles. Her unlikely partner becomes Daryl, Bart’s stoic driver and ex-convict.

Frankie’s investigation leads her to Ashley, a weary resettlement worker who describes Sabera as educated but withdrawn, trapped in an unhappy marriage with her older husband, Isaad. Sabera’s co-workers recall her exhaustion, erratic behavior, and hints of alcohol on her breath—an unlikely detail for a devout Muslim woman.

Ashley suspects deep trauma beneath the surface.

At the refugee complex, Frankie meets Nageenah, another Afghan mother who reveals that Sabera disappeared weeks ago and that Isaad left soon after, abandoning Zahra in her care. Shortly before vanishing, Isaad received a mysterious package from a courier.

Nageenah’s account suggests Sabera’s life was shadowed by danger, secrecy, and fear.

The tension escalates when local news footage shows a woman resembling Sabera fleeing a double homicide scene. Aliah insists it is her friend, while police remain skeptical.

As Frankie and Daryl pursue leads, an attempted abduction of Zahra jolts everyone—the attacker calls the child by name, indicating premeditation. Zahra, gifted with an eidetic memory, utters an enigmatic phrase: “A lock to a key for a key that has no lock.” Frankie senses the words hide an important clue.

Through Sabera’s recovered diary entries, fragments of her past emerge. After losing her family in Kabul, she accepted protection from Professor Ahmadi, her father’s colleague.

Pregnant and desperate, she agreed to marry him to ensure safety. Their marriage, however, became another form of confinement.

Her husband’s love was possessive, his authority unyielding. The diary closes with a mother’s farewell to her daughter, urging her to remember strength and hope.

Frankie’s search uncovers more grim revelations: Isaad’s body is found, fingers burned as he tried to preserve a red notebook filled with equations. The evidence points to coercion and torture.

Investigators suspect multiple parties are hunting for something Sabera possesses—perhaps tied to her mother’s past as an MI6 asset and her family’s rumored involvement in hidden wealth or coded intelligence.

Amid mounting danger, Zahra’s cryptic drawings of mathematical matrices catch attention; they may encode valuable information. A retired captain named Sanders Kurtz and his brother, Dr. Richard, surface with MI6 records linking Sabera’s psychiatric episodes and cryptic statements about someone named “Jamil. ” These documents reveal Sabera’s mental instability, postpartum trauma, and possible pregnancy.

Yet her tox screens were clean—her confusion born not from substance use but from deep psychological wounds.

As the threads converge, the narrative shifts to Sabera’s perspective. Haunted by ghosts of Kabul, she believes her cousin Habib—whom she thought dead after she killed him in self-defense—has returned.

Terrified, she hides while plotting how to keep Zahra safe. Habib, driven by greed and vengeance, teams up with Rafiq, another embittered refugee, seeking a treasure rumored to be encoded in Sabera’s inherited secrets.

Sabera’s disappearance turns into a violent chase. She is captured, beaten, and forced to reveal the code her mother left behind.

During her captivity, Rafiq and his accomplice are killed with a hammer in a desperate struggle for survival. Sabera escapes but remains hunted, carrying both guilt and terror.

Frankie and her allies, including Daryl, Aliah, Roberta (Daryl’s former parole officer), and Captain Kurtz, orchestrate a plan to protect Zahra and draw out the remaining pursuers. They lure the enemies to Bart’s snake-filled mansion, turning the eccentric house into a fortress.

When Habib invades, dragging Aliah as hostage, chaos erupts. Daryl intercepts him but is badly wounded; Sabera kills her cousin in a frenzy of release and despair.

More attackers follow, but they are outmaneuvered by the team’s traps and last-minute reinforcements.

As the dust settles, the surviving group faces new betrayals. Lilla, a British operative posing as an ally, reveals ulterior motives and poisons Sabera, claiming the secret she carries will always endanger her.

Sabera collapses and is declared dead. Her allies mourn, believing the story has closed with tragedy.

But the final twist reveals Sabera alive. Lilla and Dr. Richard faked her death to free her from pursuit. Sabera, pregnant and emotionally scarred, prepares to leave for the United Kingdom with Zahra.

Before departing, she entrusts Frankie with a bundle of letters written for her daughter—a legacy of love and truth. Frankie promises to keep her secret.

The aftermath brings quiet restoration. Daryl recovers from his injuries, Aliah reopens her deli, and Frankie continues her mission to find the lost.

Though scarred by the ordeal, she finds renewed purpose. The story closes with a sense of fragile hope—proof that even in the ruins of war and trauma, resilience endures, and love, however bruised, survives.

Characters

Sabera Ahmadi

Sabera Ahmadi stands as the emotional and moral center of Kiss Her Goodbye, a woman defined by courage, trauma, and transformation. Born into an educated and liberal Afghan family, she embodies the tension between progress and repression in her homeland.

Her childhood memories—of orchards, literature, and her mother’s secret resistance—shape a dual inheritance: tenderness and defiance. After her mother’s death and the Taliban’s return, Sabera’s life collapses.

Forced into survival, she loses her family to violence and flees Afghanistan. Her marriage to Isaad is both refuge and cage; while he offers safety, he also represents patriarchal control.

In America, Sabera struggles with displacement and fractured identity. Her mental health deteriorates under the weight of guilt and memory—haunted by ghosts, both literal and symbolic.

The discovery of her mother’s links to MI6 and her own entanglement in hidden political and familial secrets reveal a woman trapped between history and survival. Sabera’s cryptic writings—“a lock to a key for a key that has no lock”—reflect her fractured psyche and her coded defiance.

In her final moments, she demonstrates immense resolve, orchestrating her own “death” to protect her daughter and ending the cycle of violence that has shadowed her life. She emerges as a figure of resilience and tragedy—a woman shaped by war, patriarchy, and love, yet unwilling to be silenced.

Frankie Elkin

Frankie Elkin, the series’ recurring protagonist, brings a distinct lens to Sabera’s disappearance. A recovering alcoholic and self-taught investigator, Frankie is driven by an almost obsessive compulsion to find the missing—people forgotten by society.

Her life of transient purpose contrasts sharply with Sabera’s domestic imprisonment, yet both women share a profound loneliness. Frankie’s empathy, rooted in her own losses, allows her to bridge cultural divides and confront institutional indifference.

Throughout the investigation, Frankie evolves from observer to protector, risking her safety to uncover Sabera’s truth. Her skepticism about faith, law, and authority clashes with the refugees’ fatalistic hope, forcing her to confront the limits of her understanding.

Despite her flaws—pragmatic detachment, occasional arrogance—Frankie’s moral core remains intact. Her compassion for Zahra and respect for Sabera’s courage elevate her from a mere detective to a witness of human endurance.

In the end, Frankie’s narrative voice offers balance to the story’s chaos—anchoring it in humanity, grief, and redemption.

Isaad Ahmadi

Isaad Ahmadi is a complex figure whose intellect and insecurity intertwine to create both protector and oppressor. Once a respected mathematician, he becomes a refugee stripped of identity, clinging to authority within his marriage.

His relationship with Sabera oscillates between care and control—he saves her from danger in Kabul, yet exerts psychological dominance over her in exile. His obsession with logic, order, and his red notebook symbolizes his futile attempt to impose structure on a disordered world.

Isaad’s eventual murder underscores his moral ambiguity. His burned hands clutching the notebook suggest both martyrdom and guilt; he may have been complicit in the secrets Sabera’s family carried.

Isaad’s love for Zahra is real but filtered through his need for control and preservation of legacy. In death, he becomes a tragic echo of a man destroyed not by war alone, but by the loss of purpose and the corrosive effects of fear.

Zahra Ahmadi

Zahra is the fragile yet luminous thread binding the story’s chaos. Gifted with a photographic memory and a precocious intellect, she serves as both victim and vessel—carrying within her the key to her family’s secrets.

Her cryptic words—“A lock to a key for a key that has no lock”—embody the novel’s theme of encrypted trauma, where truth is both weapon and wound.

Zahra’s innocence contrasts with the darkness surrounding her. Though barely a child, she displays astonishing composure amid abduction attempts, murder, and loss.

Her bond with Sabera is profound—a transmission of strength across generations of women who refuse to surrender. When Sabera vanishes, Zahra’s survival becomes a symbol of hope and continuity, ensuring that her mother’s resilience lives on even in exile.

Aliah

Aliah, Sabera’s closest friend and fellow refugee, represents solidarity within diaspora. Her Afghan deli serves as both cultural refuge and emotional anchor for displaced women.

Loyal and outspoken, Aliah balances compassion with pragmatism, embodying the community’s fractured resilience. Her faith in Sabera’s goodness propels much of the investigation, contrasting with the cynicism of American institutions that dismiss the missing woman’s case.

Aliah’s grief and endurance make her one of the story’s emotional pillars. She experiences betrayal, fear, and eventual physical harm, yet continues to fight for truth and justice.

Through Aliah, the novel portrays the quiet heroism of ordinary women who hold communities together amid loss.

Daryl

Daryl, Frankie’s formidable companion, provides strength both literal and moral. A man with a criminal past seeking redemption, he symbolizes the possibility of transformation.

His loyalty to Frankie and courage in the face of danger humanize him beyond his imposing exterior. The bond between Daryl and Frankie deepens the emotional tone of the narrative—mutual respect born from pain.

His near-fatal wounding during the climactic confrontation underscores the cost of decency in a violent world. Daryl’s survival and slow recovery mirror the novel’s larger arc—from chaos to tentative healing—and reinforce the theme that redemption is a continuous act, not a single event.

Roberta

Roberta, Daryl’s former parole officer and dance partner, injects humor, defiance, and tenacity into the grim narrative. Fiercely independent and unflinching, she bridges law enforcement and personal loyalty.

Her pragmatism often offsets Frankie’s impulsiveness, creating a dynamic of trust and tension. Roberta’s willingness to risk herself for justice—particularly in the violent final acts—cements her as an unsung hero of the story.

Her presence highlights the idea that courage manifests in unexpected forms: in aging women who refuse to retreat, in friendships forged through shared survival, and in the simple act of showing up when others look away.

Dr. Richard

Dr. Richard and Captain Kurtz form the story’s shadowy link between humanitarian aid and espionage.

Dr. Richard, the weary physician haunted by his failures, personifies the moral cost of intervention.

His compassion contrasts with the manipulative precision of his brother, Kurtz—a strategist navigating the blurred lines between rescue and exploitation. Together, they expose the undercurrents of Western complicity in Afghan suffering.

Kurtz’s revelation about orchestrating the Ahmadis’ relocation and the staged death of Sabera redefines him as both savior and puppeteer. Their actions question whether rescue can ever be clean when entangled with intelligence and politics.

These men, despite their good intentions, embody the ethical murk at the heart of Kiss Her Goodbye.

Lilla

Lilla, the enigmatic MI6 agent, operates as both antagonist and guardian. Her ambiguous morality—poisoning, deceit, and manipulation—reflects the shadow world that shaped Sabera’s family.

She blurs the boundaries between justice and expedience, compassion and control. Lilla’s relationship with Sabera vacillates between mentorship and coercion, culminating in the faked death and escape that end the novel.

In many ways, Lilla represents the embodiment of cold pragmatism that contrasts with Sabera’s emotional authenticity. She survives by deception, while Sabera survives by faith in truth.

Together, they frame the novel’s final paradox: that survival often demands both.

Themes

Identity and Displacement

The narrative of Kiss Her Goodbye by Lisa Gardner explores identity as a fragile construct continuously reshaped by displacement, trauma, and survival. Sabera’s journey—from an educated Afghan girl to a refugee woman navigating life in America—reflects how identity becomes fragmented when history, homeland, and personal agency are stripped away.

Her early life in Afghanistan anchors her in familial love and cultural richness, but political collapse transforms her into someone unrecognizable even to herself. The forced migrations of her family, the death of her loved ones, and her marriage of necessity to Isaad all erode her sense of belonging.

In Tucson, the alien environment amplifies her inner dislocation; her voice becomes one of silence and concealment rather than expression. Yet within that silence lies endurance—the identity of a survivor who adapts even when belonging is denied.

Through Frankie Elkin, the novel adds a mirror image: a woman who is rootless by choice but equally alienated, existing on society’s margins while seeking lost people as a way to piece together her own fractured self. Both women embody different versions of exile—Sabera’s imposed by war and patriarchy, Frankie’s self-inflicted through guilt and loss.

The theme underscores how identity is not a fixed inheritance but an evolving response to rupture and memory, revealing that survival often demands the reshaping of the self until it becomes both shield and disguise.

Female Resistance and Silence

The story’s female characters—Sabera, her mother, Aliah, Ashley, and even Frankie—carry the shared burden of resistance conducted through silence, secrecy, and small acts of defiance. In a patriarchal world where open rebellion is punished, their endurance becomes an unspoken language of survival.

Sabera’s mother embodies this resistance first: a woman who trades forbidden goods and information under the gaze of conservative men, nurturing her daughter’s quiet strength with coded lessons. Sabera inherits this mode of defiance, turning secrecy into her armor when faced with political oppression, domestic control, and cultural exile.

Her silence conceals not weakness but strategy, a way to live under scrutiny without surrendering autonomy. In Tucson, this resistance manifests differently but with equal potency—Frankie’s refusal to conform to expectations of femininity or domesticity, Ashley’s exhaustion within bureaucratic neglect, Aliah’s steadfast faith amid discrimination.

Their struggles intersect through shared understanding rather than overt rebellion, emphasizing that in oppressive systems, women’s survival itself becomes an act of defiance. The novel transforms silence from a symbol of submission into one of moral courage and endurance.

By portraying resistance as intimate and interior, Gardner reveals how women navigate power not through confrontation alone but through endurance, coded communication, and moral clarity in a world that repeatedly tries to erase them.

Trauma, Memory, and Inheritance

Trauma in Kiss Her Goodbye functions not merely as aftermath but as a living, inherited force that shapes generations. Sabera’s memories of violence, her dissociative episodes, and the hallucinations of her dead family reveal how unprocessed grief becomes a haunting that transcends time and geography.

Her daughter Zahra’s eidetic memory, while extraordinary, represents the same burden—an inability to forget. In contrast, Frankie’s emotional numbness and obsession with rescuing others highlight another form of trauma: one defined by guilt and self-erasure.

Gardner constructs trauma as an ecosystem of echoes where survival depends on selective forgetting, yet the narrative insists that forgetting is impossible. Each character becomes a vessel for inherited pain—Sabera from her mother, Zahra from Sabera, and Frankie from her own buried past.

The novel portrays trauma as cyclical rather than linear, showing how it distorts perception, fractures relationships, and challenges identity. It also connects personal and political suffering, linking individual breakdowns to larger historical violence.

The fusion of memory and madness blurs boundaries between reality and delusion, demonstrating how those who endure trauma live in two worlds at once: the one that is gone and the one that demands endurance. Gardner treats memory not as a tool of healing but as a test of survival—the question is not whether to remember, but how to live with remembering.

Power, Control, and Patriarchy

Power dynamics pervade the novel, revealing the many ways control manifests—from the intimate to the institutional. Isaad’s dominance over Sabera mirrors the systemic subjugation of women in both Afghan and Western contexts.

His control is intellectual and paternalistic, disguised as protection but functioning as possession. The men who orbit Sabera—her uncles, Habib, Rafiq—represent different shades of patriarchal violence: coercion, entitlement, exploitation.

Yet Gardner extends the critique beyond the personal. Bureaucratic systems that process refugees, intelligence agencies that manipulate lives for geopolitical ends, and law enforcement that dismisses missing women—all become embodiments of structural control.

Frankie’s role as an investigator highlights this theme further: she operates within the same masculine-coded realm of authority but reclaims it through empathy and persistence. Her power comes not from domination but from witnessing and understanding.

In contrast, the state and its male agents wield power through erasure—reducing individuals to cases, refugees to statistics, women to suspects. Sabera’s final act of reclaiming agency, even amid deception and staged death, asserts a moral reversal: survival and motherhood become her final forms of power.

The novel ultimately suggests that true control lies not in coercion but in the refusal to submit, even when silence and secrecy are the only available weapons.

Guilt, Redemption, and Moral Ambiguity

At its core, Kiss Her Goodbye is a meditation on guilt and the human longing for redemption. Every major character is haunted by a moral wound—Sabera by the killing of her cousin Habib, Frankie by the unnamed losses that drive her nomadic crusade, Isaad by his complicity in violence and deception.

Their actions oscillate between mercy and vengeance, showing how guilt distorts intention. Gardner’s narrative refuses to divide her characters into simple victims or villains; instead, it situates them within moral gray zones where survival often demands transgression.

Sabera’s guilt evolves into self-punishment, manifesting in hallucinations and breakdowns, while Frankie’s need to “find the lost” becomes a penance that isolates her from life. Yet redemption, in Gardner’s world, does not arise from forgiveness or absolution—it comes through acknowledgment and endurance.

When Sabera sacrifices her identity to protect Zahra, she performs the ultimate act of moral clarity: choosing life over vengeance, concealment over destruction. Frankie’s decision to protect that secret continues the cycle of imperfect redemption, suggesting that morality is not about purity but persistence in doing what remains right after everything else has fallen apart.

In this moral landscape, guilt becomes both a curse and a compass, guiding broken people toward acts of quiet grace.