La Casa de Bernarda Alba Summary, Characters and Themes

La Casa de Bernarda Alba is a play written by the renowned Spanish poet and playwright Federico García Lorca. It focuses on the themes of repression, female desire, and social convention in rural Spain.

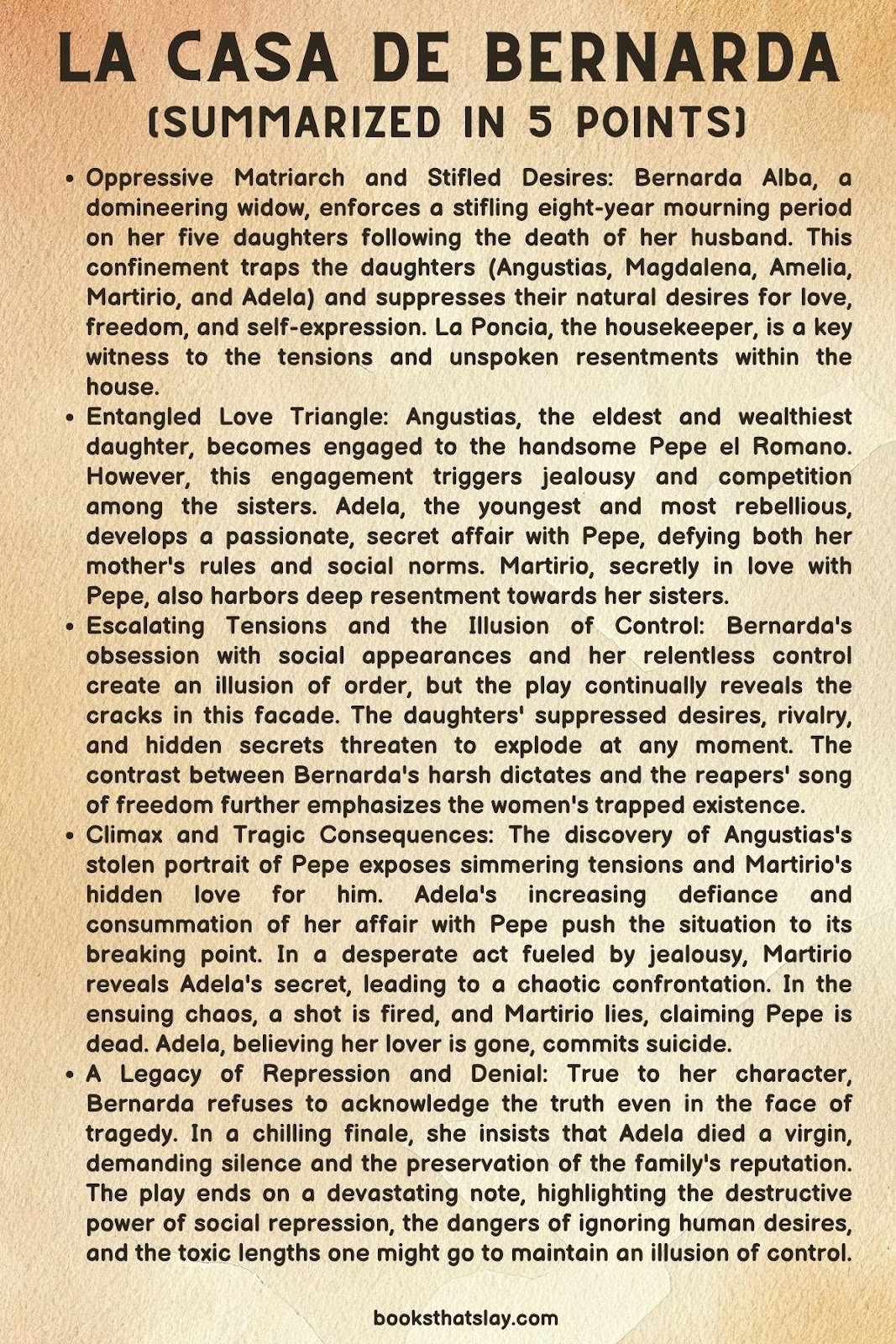

The story revolves around Bernarda Alba, an overbearing widow enforcing a strict eight-year mourning period upon her five daughters following her husband’s death. The play explores the daughters’ stifled desires and the simmering tensions within the household, ultimately leading to a tragic climax.

Summary

Act I

In a remote Spanish village, the tyrannical Bernarda Alba imposes a strict eight-year mourning period on her five daughters following her husband’s death.

The daughters – Angustias, Magdalena, Amelia, Martirio, and Adela – are confined to the house, their desires and prospects stifled by their mother’s oppressive rule.

Bernarda’s iron-fisted control extends to the household staff, particularly the long-suffering La Poncia, her housekeeper. An atmosphere of resentment and unspoken desires simmers beneath the surface.

Meanwhile, Bernarda’s elderly mother, Maria Josefa, locked away due to her dementia, represents the madness lurking beneath the façade of order.

Angustias, the eldest and the only daughter with a substantial inheritance, attracts the attention of the handsome Pepe el Romano. The news sparks envy and despair among her sisters, particularly the passionate Adela, who defies her mother’s rules, revealing cracks in Bernarda’s regime.

Act II

Tensions escalate with the sisters’ suppressed desires and Bernarda’s unyielding authority. Adela, consumed by longing, secretly meets Pepe at night, a dangerous transgression. La Poncia, privy to the secret, warns Adela of the consequences, but her warnings are ignored.

The arrival of handsome reapers in the village momentarily disrupts the monotony, further highlighting the women’s trapped existence.

Matters reach a crisis point when Angustias’ portrait of Pepe goes missing, and the subsequent investigation reveals it in Martirio’s possession. Martirio, silently in love with Pepe, is exposed and humiliated. Bernarda’s focus on outward appearances and propriety blinds her to the growing turmoil within her household.

The act ends with a shocking act of violence outside the house – a young woman who gave birth out of wedlock has murdered her child.

Bernarda and her daughters join the frenzied calls for punishment, except Adela, whose defiance foreshadows a tragic collision.

Act III

A deceptive calm settles in Bernarda’s house as Angustias and Pepe’s engagement is announced.

However, Angustias senses Pepe’s distance and growing distraction. Adela, consumed by desire and desperation, becomes increasingly rebellious, refusing to be controlled. La Poncia, recognizing the imminent danger, attempts once more to awaken Bernarda to the reality of her daughters’ suffering, but her pleas fall on deaf ears.

Driven by passion, Adela defies all warnings and consummates her relationship with Pepe. Martirio, fueled by jealousy and a sense of betrayal, discovers the truth and exposes Adela’s actions.

Chaos erupts as Bernarda attempts to violently assert control. In a climactic moment, Adela breaks Bernarda’s cane – a symbol of her oppressive authority – and declares her determination to defy her mother.

Bernarda calls for a gun, and a shot rings out. Martirio falsely proclaims Pepe’s death, leading to Adela’s devastating suicide.

In a chilling display of denial and obsession with appearances, Bernarda insists on covering up the truth, demanding silence and the pretense that Adela died a virgin.

The play concludes with Bernarda’s ruthless silencing of any truth or emotion, leaving the audience with the haunting image of a family destroyed by repression, hidden desires, and the destructive pursuit of social conformity.

Characters

Bernarda Alba

The domineering matriarch at the center of the play, Bernarda Alba represents the suffocating forces of tradition, social convention, and female repression.

Her obsession with outward appearances and the family’s reputation drives her tyrannical rule over her household. She believes a woman’s place is in the home, obedient and silent.

This belief system blinds her to the bubbling passions and desires beneath the surface of her house, ultimately leading to tragedy. Bernarda is not simply cruel, but rather a product of her own repressed upbringing, leading her to perpetuate the cycle onto her daughters.

Even at the play’s end, after Adela’s suicide, she remains fixated on appearances, illustrating the deep-rooted nature of societal pressures.

Adela

The youngest and most rebellious of the daughters, Adela embodies a fierce desire for freedom and self-expression.

Her defiance of her mother’s rules and her passionate pursuit of love with Pepe make her a tragic figure.

Unlike her sisters, Adela refuses to be stifled by tradition and chooses to embrace her desires fully, even knowing the consequences. Her death is not an act of weakness, but a final act of rebellion against the oppressive forces that sought to contain her spirit.

Martirio

Plagued by jealousy and bitterness, Martirio represents the tragic consequences of unfulfilled desire.

Secretly in love with Pepe herself, she experiences a tortured existence, her own passions simmering under a veil of quiet resentment. Martirio’s ultimate betrayal of Adela stems from a twisted sense of entitlement and the despair of knowing she can never have what she truly desires.

Her character embodies the corrosive effect of repression within the female sphere and the dangers of harboring internalized longing.

La Poncia

Bernarda’s housekeeper and confidante, La Poncia is a complex figure straddling the line between authority and servitude.

While she shares Bernarda’s belief in tradition and social order, her years of service in the household have given her an intimate understanding of the family’s hidden dynamics.

La Poncia consistently voices concerns and warnings, but she ultimately remains powerless to alter events. She represents the voice of practicality and reason, yet her loyalties ultimately lie with preserving the existing hierarchy within the house.

Maria Josefa

Bernarda’s elderly mother, afflicted by dementia, Maria Josefa is a symbolic figure within the play.

Her confinement highlights the madness that can arise from a life of repression. Despite her fractured ramblings, Maria Josefa often acts as an oracle, speaking harsh truths that the other characters try to ignore.

Her yearning for freedom and her repeated demands to be let out near the ocean reflect the suppressed desires of all the women trapped within Bernarda’s house.

Themes

Repression and the Destructive Power of Social Conformity

Lorca explores the suffocating consequences of the rigid social expectations placed upon women in rural Spain during his time.

Bernarda Alba represents this oppressive force, dictating an extreme mourning period and severe limitations on her daughters’ freedom of movement and expression.

This enforced repression has dire consequences. Angustias may have inherited wealth, but she’s trapped in a loveless engagement. Martirio and Amelia yearn for love and connection but are doomed to remain unmarried and unseen.

The vibrant Adela, the most defiant of the sisters, suffers the most, and her passion ultimately leads to her tragic demise.

Lorca challenges the notion that upholding appearances and adhering to social norms is worth the sacrifice of individual freedom and happiness.

The Conflict Between Desire and Authority

A central tension in the play is the clash between the daughters’ natural desires for love, freedom, and self-expression and the iron-fisted authority of their mother. Bernarda symbolizes the old, patriarchal order, suppressing her daughters’ individuality to maintain control.

The conflict becomes most evident in Adela, whose defiance of her mother escalates throughout the play. Her defiance culminates in her illicit relationship with Pepe and eventually the shattering of Bernarda’s cane – a pivotal moment symbolizing her rejection of Bernarda’s rule.

Lorca starkly highlights the danger of suppressing basic human needs and emotions, foreshadowing the inevitable tragedy such oppression brings.

The Illusion of Honor and Reputation

Bernarda’s obsession with maintaining an outward appearance of respectability and traditional values masks a dysfunctional, fractured household. Her primary concern after Adela’s suicide isn’t her daughter’s despair but the preservation of the family’s reputation.

She insists on framing Adela’s death as that of a virgin, denying the reality of the situation.

This hypocrisy reveals that upholding appearances becomes more important than genuine love or familial connection.

Lorca forces the audience to confront the emptiness and destructive nature of adhering to a rigid social code that values reputation above all else, even at the cost of individual happiness and even life itself.