Lazarus Man Summary, Characters and Themes

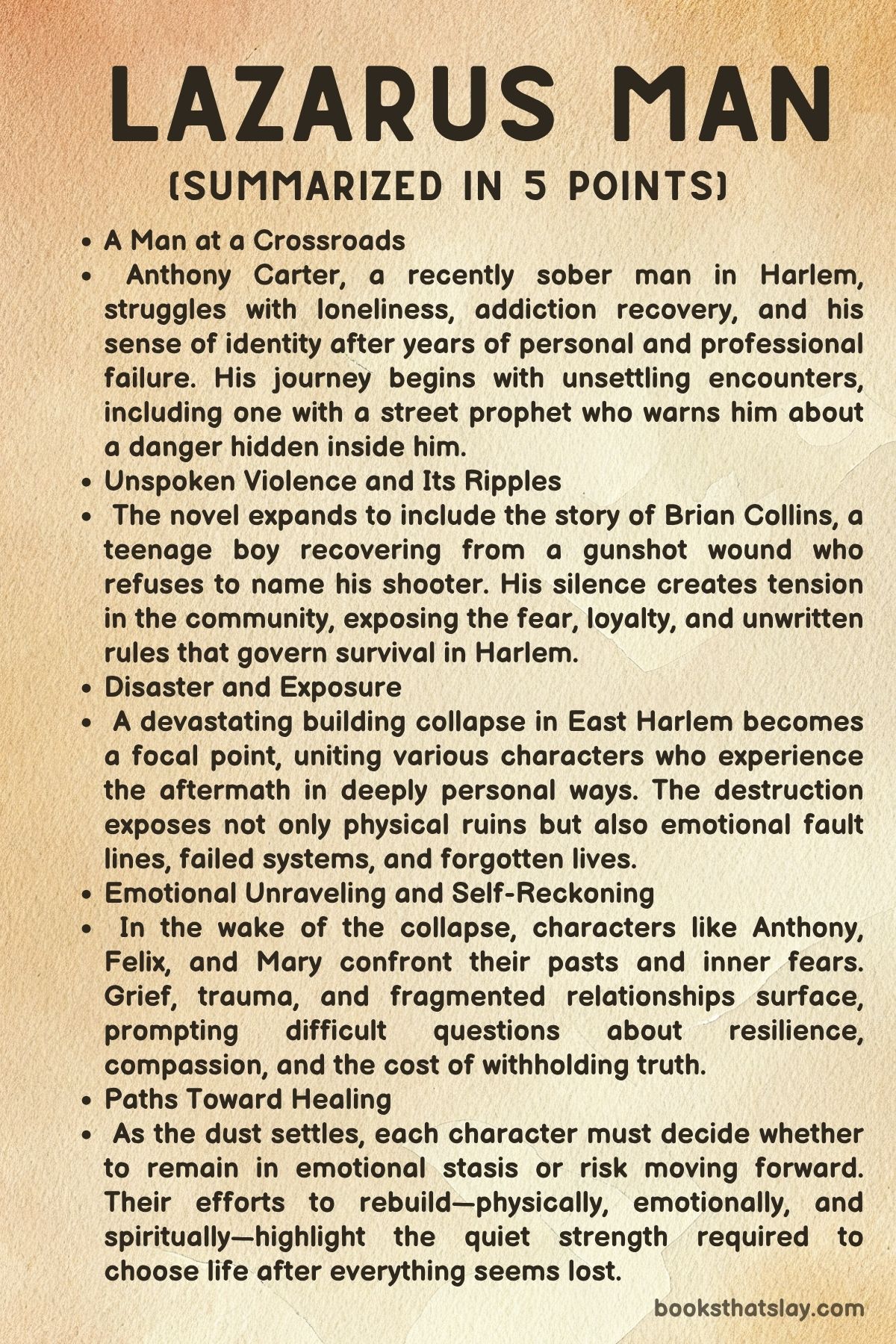

Lazarus Man by Richard Price is a multi-layered, emotionally resonant exploration of Harlem, tracing the lives of several interconnected characters before and after a building collapse disrupts their community. Through a kaleidoscopic narrative told in alternating perspectives, the novel examines themes of identity, grief, systemic neglect, resilience, and redemption.

At its core, the book grapples with how people survive personal and collective trauma, and how moments of crisis reveal the cracks and fortitudes within a society. Price uses Harlem not just as a backdrop, but as a living character, capturing the nuance of urban life through the voices of those often unseen in mainstream storytelling.

Summary

The novel opens with Anthony Carter, a 42-year-old former teacher trying to rebuild his life after years of addiction and personal failures. Once a promising academic at Columbia University, Anthony’s downward spiral was triggered by self-sabotage, grief over his father’s death, and feelings of racial ambiguity—being biracial and light-skinned, he struggles with society’s inability to categorize him.

Now recently sober and unemployed, he drifts through Harlem’s bars and streets, looking for solace or distraction. A brief encounter with a woman named Andrea ends without substance, and Anthony masks his truth with fantastical lies, such as claiming to be a clown college dropout.

His story illustrates the ache of unrealized potential and the quiet shame of missed chances.

Later that night, Anthony stumbles into a frenzied Pentecostal church service led by Prophetess Irene. The scene is chaotic and powerful, Irene’s performance feeling both manipulative and strangely authentic.

She calls out Anthony’s hidden pain in front of the congregation, giving him a fleeting sense of visibility and spiritual possibility. Shaken, he returns to his parents’ old apartment, a physical reminder of his fractured upbringing, and prepares for a job interview with cautious hope.

Parallel stories begin to unfold. Anne Collins, a postal worker and mother, confronts a feared neighborhood figure named Junior White to advocate for her teenage son Brian, who has recently been shot.

Her emotional strength and veiled threats demonstrate a fierce maternal drive to protect her child against the normalization of violence. Her story parallels Anthony’s in its exploration of survival—not from drugs or emotional ruin, but from the literal threat of street violence.

Another central character, Felix Pearl, a 24-year-old adopted videographer, lives in a brownstone with an eclectic mix of tenants. Plagued by unsettling encounters and a compulsive need to film everything around him, Felix’s world is altered by a catastrophic building collapse that happens early one morning.

The explosion throws Harlem into chaos: smoke clogs the air, alarms scream, and panic spreads. Felix races outside to document the devastation, momentarily helping a survivor before losing his camera in the confusion.

This event becomes both a literal and symbolic center of gravity in the novel, representing the randomness of disaster and the unpredictability of life in an urban environment.

In the wake of the explosion, other narratives arise. Royal Davis, a funeral director with financial troubles, is filming a zombie-themed student project when the collapse occurs.

The irony is sharp—he plays dead while real death explodes nearby. Mary Roe, a seasoned but emotionally frazzled detective, is among the first responders.

Her response is both professional and deeply maternal, as she processes the wreckage while still carrying the emotional weight of a past elevator accident that traumatized her family.

As the investigation into the collapse begins, Mary finds herself mired in logistical and emotional complexity. Many tenants remain unaccounted for due to the informal and fragmented nature of housing in Harlem—ghost tenants, undocumented individuals, and multi-family units make data collection nearly impossible.

She grows especially preoccupied with the case of Christopher Diaz, a man who remains missing and whose story takes on personal significance. Mary’s investigations are not just procedural but deeply connected to her sense of justice and emotional balance.

Meanwhile, Felix continues to document the aftermath. He oscillates between detached observer and overwhelmed participant, photographing mourners and street scenes, absorbing their grief and confusion.

He also begins working on a mitigation video for Micah Wade, a teenager who stabbed another boy. The video reveals painful truths about Micah’s past—his abuse at the hands of his father, his mother’s passivity, and his exposure to violence—all of which illuminate the human costs behind acts of crime.

Felix’s emotional involvement in this project underscores his shift from voyeur to empathetic witness.

Mary’s personal life continues to unravel. Her relationship with her ex-husband Jimmy is emotionally complicated, marked by residual affection and ongoing co-parenting of their sons.

She attempts to shield her boys from urban myths and literal danger alike while confronting her own emotional shortcomings. Her need for order and truth is constantly challenged by the ambiguity of her cases and her internal contradictions.

As the city reels from the collapse, a community rally organized by Calvin Ray—a former convict turned youth mentor—offers a moment of collective reflection and resistance. Calvin speaks out against the “Death-style” that haunts the projects, urging youth toward change.

Anthony, now perceived as a miracle survivor of the collapse, delivers a passionate speech about rebirth and divine intervention. Though his words inspire many, some—including Mary—remain skeptical of his authenticity.

Anthony becomes a public figure, speaking at rallies and funerals, but privately he is tormented by doubts. A critical moment comes when Mary presents him with footage suggesting he wasn’t buried in rubble at all.

Her decision not to expose him immediately reflects her own complicated feelings—curiosity, empathy, and a desire to believe in something genuine.

As Anthony’s fame grows, so does his inner turmoil. His relationship with Anne collapses after a failed attempt to reconnect with his estranged daughter Willa ends in rejection.

At a pivotal funeral service, his speech about surviving the collapse once again moves the audience, though a grieving widow challenges his narrative. Later, Mary discovers the truth about Christopher Diaz—that he was not in the building during the collapse but was spending the night with another woman while his wife died.

Her confrontation with him is tinged with compassion, showing growth in her own emotional journey.

The story concludes at a memorial for the collapse victims. Anthony, finally stripped of pretense, chooses to honor the deceased rather than glorify his own survival.

In doing so, he relinquishes the false narrative of divine selection and embraces a humbler, more communal form of redemption. Mary, still grappling with her loneliness and doubt, finds a sense of grounding in her continued pursuit of justice and truth.

In the novel’s closing moments, Anthony’s tentative phone call with Willa suggests a fragile yet real hope for reconnection. Though nothing is neatly resolved, the characters emerge from their private and shared traumas with a deeper awareness of their limitations, their responsibilities, and their capacity for grace.

Lazarus Man closes not with triumphant redemption but with the quiet endurance of people learning to live with truth, however fractured it may be.

Characters

Anthony Carter

Anthony Carter is the emotional and thematic center of Lazarus Man, a character steeped in contradiction, shame, and the desperate pursuit of redemption. At 42, Anthony is a man stalled by the inertia of his past—a once-promising academic, expelled from Columbia not due to financial hardship, as he claims, but because of an act of self-sabotage rooted in profound grief after his father’s death.

The loss of his father, a white social justice educator whose lofty ideals Anthony never felt worthy of inheriting, haunts him like a ghostly standard he can neither live up to nor entirely reject. Caught between racial identities due to his biracial heritage and light skin, Anthony embodies a kind of existential limbo, not just between Black and white, but between truth and illusion, sobriety and addiction, collapse and rebirth.

His survival of the building collapse launches him into a reluctant public role as a symbol of hope, a role he both clings to and internally questions. His speech at a community funeral, imbued with grace and insight, resonates deeply, even as it draws doubt from those like Mary who seek empirical truth.

Yet when presented with video evidence that contradicts his version of events, Anthony chooses not to double down on falsehood but instead to reframe his survival story as an act of communal remembrance rather than divine salvation. His final shift—from self-mythologizer to humble witness—marks his moral evolution, culminating in a fragile yet real effort to reconnect with his estranged daughter, Willa.

Anthony is ultimately portrayed as a man learning to live with the ambiguity of grace: not chosen, but choosing.

Felix Pearl

Felix Pearl represents a different kind of search for meaning—one shaped by the lens of a camera and the yearning to document rather than intervene. A 24-year-old adopted videographer, Felix is both an observer and a participant in Harlem’s daily turbulence, his compulsive filming both a defense mechanism and a moral project.

Traumatized by a disturbing subway encounter and alienated by his own social awkwardness, Felix drifts between the earnestness of a documentarian and the naivety of a child seeking connection. His camera is both shield and sword, a way to shape chaos into narrative, to locate beauty or at least coherence in grief.

When the building collapses, Felix is one of the first on the scene, capturing devastation through his lens until his camera is stolen, symbolizing the loss of control over the stories he so desperately wants to tell. Yet his character arc moves from that of a passive recorder to someone more emotionally involved, seen in his encounter with Crystal, who cons him with a fantastical story about a dog.

Rather than respond with anger, Felix admires her storytelling, revealing his deep hunger for authenticity and emotional resonance. His collaboration with Royal and involvement in legal mitigation videos further expose him to the complexities of restorative justice and moral ambiguity, especially when documenting the story of Micah Wade.

In the end, Felix evolves into a witness with empathy—not just someone who sees, but someone who tries to understand, capturing not just images but the fractured humanity within them.

Mary Roe

Detective Mary Roe is one of the most psychologically intricate figures in Lazarus Man, caught between the rigidity of law enforcement and the fluid, messy terrain of emotional truth. Assigned to Community Affairs, Mary operates as a conduit between institutional protocol and grassroots trauma, navigating a Harlem neighborhood where the boundaries between police and public, justice and futility, are constantly shifting.

Mary’s investigative instincts are sharp, but they are deeply entwined with a private yearning for connection, meaning, and maternal validation. Her personal life is frayed by a complicated co-parenting arrangement with her ex-husband Jimmy and a lingering trauma from a past elevator accident involving one of her sons—a moment that reset her priorities and exposed her vulnerabilities.

She approaches Anthony with equal parts suspicion and fascination, drawn to his eloquence yet unable to fully believe in his story of miraculous survival. Her pursuit of truth is not driven by cynicism but by an urgent need to reconcile the chaos around her with something solid, something real.

When she uncovers evidence that Anthony may not have been buried in the collapse as he claimed, she does not seek to expose him but rather confronts him with compassion, enabling his transformation without enforcing humiliation. Mary’s strength lies not in heroism but in her capacity for moral clarity amid ambiguity.

Her eventual confrontation with the missing Christopher Diaz is similarly layered—not about punishment but about reckoning. In the end, Mary’s journey is about learning to balance duty with empathy, and skepticism with faith in small, human redemptions.

Anne Collins

Anne Collins, a postal worker and fiercely protective mother, represents the working-class backbone of Harlem’s community. Her role in Lazarus Man is shaped by her tenacious advocacy for her son Brian, who was recently shot in a neighborhood rife with violence and intimidation.

Anne confronts Junior White, a figure of authority in the local underground hierarchy, with a blend of veiled threats and unflinching maternal courage. Her power is not institutional but emotional—rooted in a lifetime of raising a child alone while navigating a dangerous social landscape.

She is not idealized; her skepticism toward Anthony’s rise as a symbolic figure is pointed and insightful. Despite being drawn to his vulnerability, she remains grounded in her own truths and refuses to be easily seduced by lofty speeches.

Her eventual breakup with Anthony stems from this clarity—she can recognize charisma, but she knows it is no substitute for accountability. Anne’s emotional intelligence is grounded in lived experience.

She is a realist who still dares to hope, and her refusal to be either victim or saint gives her a moral authority that anchors the novel’s broader themes of resilience and justice.

Royal Davis

Royal Davis is a man who straddles the border between reverence and regret. As a funeral home director, Royal is professionally surrounded by death, yet personally distanced from any authentic sense of closure or fulfillment.

Once a promising basketball player, his transition into funeral services was a concession to familial expectations and economic realities rather than a calling. Royal’s foray into promotional videos and his odd participation in a student zombie film offer a glimpse into his internal conflict—a man trying to revive a sense of relevance and creativity in the twilight of a compromised life.

His interaction with Felix marks a turning point, especially after learning of Felix’s father’s farewell video. That moment bridges the generational and emotional gap between them, allowing Royal to connect with someone else’s grief in a way he has been unable to access his own.

His ambivalence toward his role in the community is further highlighted by the irony of his presence at the explosion site in zombie makeup, a grotesque symbol of life imitating death. Yet by the end, Royal, like many others, edges closer to a fragile sense of meaning—not through transformation but through acknowledgment of what he has become and the small ways he might still serve.

Calvin Ray

Calvin Ray embodies the redemptive potential of mentorship and activism within a fractured urban environment. A reformed convict turned youth advocate, Calvin orchestrates a community rally aimed at disrupting the “Death-style” culture that he believes is strangling young Black boys in Harlem.

His speech is not merely rhetoric—it is a distillation of hard-earned wisdom and personal transformation. Calvin’s work as a Credible Messenger bridges the institutional and emotional divides between authority and youth, providing a model for restorative engagement.

His support of Micah Wade’s mitigation video, alongside his leadership in the community, shows a man who has taken his pain and weaponized it into hope for others. He is not naïve—he understands the systemic forces at play—but he believes in the incremental power of narrative, mentorship, and visibility.

His role in the narrative is both symbolic and functional, offering a vision of what healing might look like when driven by those who have walked the darkest paths and returned with purpose.

Micah Wade

Micah Wade is both a perpetrator and a victim, his stabbing of another boy framed within a deeply tragic backstory of familial abuse and emotional neglect. Through the mitigation video Felix helps create, Micah’s story emerges not as an excuse but as a plea for understanding—a desperate attempt to map violence onto a blueprint of trauma.

Raised by a violent father and a mother too passive to protect him, Micah is shaped by a childhood devoid of safety or validation. His quiet demeanor masks deep wells of rage and confusion, emotions that erupt in the fatal incident that places him in the criminal system.

What makes Micah’s arc compelling is the rawness of his truth—how candidly he admits fear, remorse, and yearning. Through testimonies by his brother JC and activist Calvin Ray, the novel excavates the layers behind his act, revealing a systemic failure that extends far beyond one violent moment.

Micah represents the limits of restorative justice in a society unwilling to reckon with its own complicity in producing broken boys who become broken men. Yet in his honesty, he also embodies the quiet, flickering hope that truth-telling, if not healing, is still possible.

Crystal

Crystal is a peripheral but vivid presence in Felix’s arc, a con artist who dupes him with a dramatic tale about a lost dog in order to steal money. Yet rather than become a symbol of betrayal, Crystal’s interaction with Felix unfolds as a surprising moment of connection.

Felix, rather than lashing out, is impressed by her theatrical talent and drawn to the emotional conviction in her storytelling. Crystal is not fleshed out in depth, but her presence lingers because she encapsulates the blurred lines between performance and truth that ripple through the novel.

In a world where everyone is trying to make their pain legible, Crystal’s con becomes another kind of desperate narrative—one that elicits empathy even in its deception.

Themes

Identity and the Struggle for Self-Definition

Anthony Carter’s arc in Lazarus Man reveals the sustained difficulty of locating a coherent sense of self in a world that demands legibility. His biracial background and ambiguous appearance unsettle both social and internal boundaries.

Throughout his journey, Anthony is positioned in a liminal space—not just racially, but morally and emotionally—as someone constantly under reconstruction. From lying about attending clown college to hiding the truth behind his expulsion from Columbia, his interactions are layered with efforts to redefine or obscure who he truly is.

His father’s legacy as a radical white social justice educator adds another layer of complexity: a burden of ideological inheritance that both inspires and suffocates. Anthony’s failure to live up to these inherited ideals becomes a recurring source of shame, underscoring his conflicted relationship with his own origins.

His brief moments of emotional clarity—during the church service or funeral speech—offer glimpses of a man desperate not for reinvention but for reconciliation with the fragmented parts of himself. Even his role as a community figure toward the novel’s end teeters between genuine service and performative redemption, constantly questioning whether his newly claimed identity is truth or illusion.

In essence, the theme of identity permeates every narrative turn, capturing the haunting fluidity of being in a society that privileges certainty.

Survival, Trauma, and the Residue of Catastrophe

The aftermath of the building collapse becomes more than a physical disaster; it functions as a metaphor for the enduring fragility of survival. Characters like Anthony, Felix, and Mary walk through their lives bearing psychological injuries that predate the collapse, yet the incident acts as a catalyst, forcing submerged traumas to the surface.

For Anthony, survival raises uncomfortable questions about why he lived while others perished. His subsequent speeches may inspire some, but they also stir suspicion, even in himself, suggesting that survival can carry its own guilt and confusion.

Mary’s compulsive investigation of the collapse and the case of the missing Christopher Diaz reveal her personal entanglement with the need to understand loss. The chaos of the incident feeds her obsession with control and closure, reflecting how trauma distorts professional duty into something deeply personal.

Felix, initially viewing the catastrophe through a lens, cannot maintain detachment. His camera becomes both shield and curse—a device that captures suffering but also distances him from it until it no longer can.

He loses the camera in the midst of saving someone, suggesting that true survival requires participation, not just observation. This theme lays bare the emotional and spiritual aftermath of physical disasters and questions the stories survivors must tell themselves in order to continue living.

Community, Disconnection, and the Search for Belonging

Harlem itself emerges as a restless character in Lazarus Man, a terrain of stoops, corner stores, scaffolding gyms, and street-level negotiations of trust. The community is portrayed as vibrant yet unstable, intimate yet fractured.

Characters like Anne Collins assert themselves with defiant strength—her confrontation with Junior White for her son’s safety is both an act of maternal love and communal assertion. Calvin’s rally, organized as a push against what he calls a “Death-style,” provides a rare moment of unity in a neighborhood plagued by suspicion, violence, and despair.

Yet even this moment is underscored by doubt, especially around Anthony’s speech, whose eloquence is both moving and suspect. The event becomes a test of communal belief—can people trust each other, or are all redemptive narratives suspect in an environment worn down by disappointment?

Felix’s failed attempt to help a con artist, and his subsequent admiration for her performance, speaks to the desperation for human connection in a world where scams masquerade as stories. Royal’s funeral home and his own internal ambivalence reflect how rituals of death become backdrops for ongoing negotiations of belonging and loss.

Whether through organized rallies, intimate funerals, or stoop conversations, the novel examines how people forge connections despite—and sometimes because of—their failures to fully know one another.

Redemption and the Burden of Public Persona

Throughout the narrative, Anthony’s transformation from anonymous addict to quasi-public figure reveals the unstable grounds of redemption when mediated through performance. His speech at the funeral is a moment of raw self-exposure, but it also borders on self-aggrandizement, prompting a widow to publicly challenge its sincerity.

This moment captures the central tension in the redemptive arc: the line between authenticity and performance is thin, often invisible. Later, when Mary presents Anthony with footage that challenges his account of the collapse, his entire identity teeters on collapse.

Yet rather than retreat into defensiveness, Anthony makes a significant pivot. At the memorial, he chooses to speak only of the dead, relinquishing the spotlight he had grown to occupy.

Redemption, in this telling, becomes a quieter, more anonymous act—not rooted in applause but in the relinquishing of ego. Felix’s arc mirrors this in smaller scale.

His growing awareness that documentation is not enough, that empathy and participation are necessary, signals his moral growth. Royal, meanwhile, finally connects with Felix through a story about a deathbed video, recognizing shared emotional needs masked by stoicism.

The book questions whether redemption is possible without illusion and what it costs to maintain or abandon the narratives that redeem us in the eyes of others.

Motherhood, Masculinity, and Emotional Inheritance

Mary Roe’s storyline broadens the novel’s examination of gender and care. Her role as a detective and mother brings with it competing mandates—professional rationality and emotional protection.

Her fraught relationship with her ex-husband Jimmy, shaped by tenderness, bitterness, and unspoken injuries, underscores how familial obligations persist even when romantic ties disintegrate. Mary’s parenting is colored by trauma, particularly a past elevator accident that reoriented her relationship to fear and control.

Her protective instincts manifest in both literal and symbolic battles—against myths like the Candyman and against the emotional erosion of her sons. At the same time, the subplot surrounding Micah Wade, the young man accused of stabbing another boy, offers a piercing commentary on the emotional inheritance passed down through fathers and absent parenting.

The raw interviews Felix films for Micah’s mitigation video reveal cycles of violence, shame, and neglect, exposing how masculine identity often forms in the shadow of abandonment or aggression. Calvin’s efforts as a mentor represent a redemptive counterpoint, but even his message of transformation is met with doubt.

The theme underscores how gendered expectations—whether of the protective mother or the emotionally armored man—can shape, constrain, or warp the path toward healing.

Truth, Belief, and the Ethics of Witnessing

A core question that arises again and again in Lazarus Man is: what is truth, and who gets to decide it? Anthony’s potentially fabricated survival story functions as a mirror to the community’s hunger for something transcendent, something meaningful amidst devastation.

Mary’s decision not to expose him, despite having evidence that casts doubt on his claims, becomes a moral act that prioritizes collective healing over forensic certainty. Felix’s role as cameraman also places him at the junction of truth and narrative.

His camera becomes a tool of testimony, but also of intrusion, and at times, deception. When he is mistaken for a predator while photographing children, it highlights how witnessing can be misread, weaponized, or corrupted.

Even in his interactions with con artist Crystal, the boundary between truth and performance is never entirely clear. These tensions also emerge in the legal defense storyline around Micah Wade—what parts of a person’s life are considered admissible truth, and what gets excluded as irrelevant backstory?

Across these arcs, the novel insists that truth is rarely neat and belief is always colored by context. The ethics of witnessing—whether as detective, photographer, survivor, or parent—are central to the novel’s moral architecture, raising questions about justice, empathy, and the price of certainty.