Let’s Call Her Barbie Summary, Characters and Themes

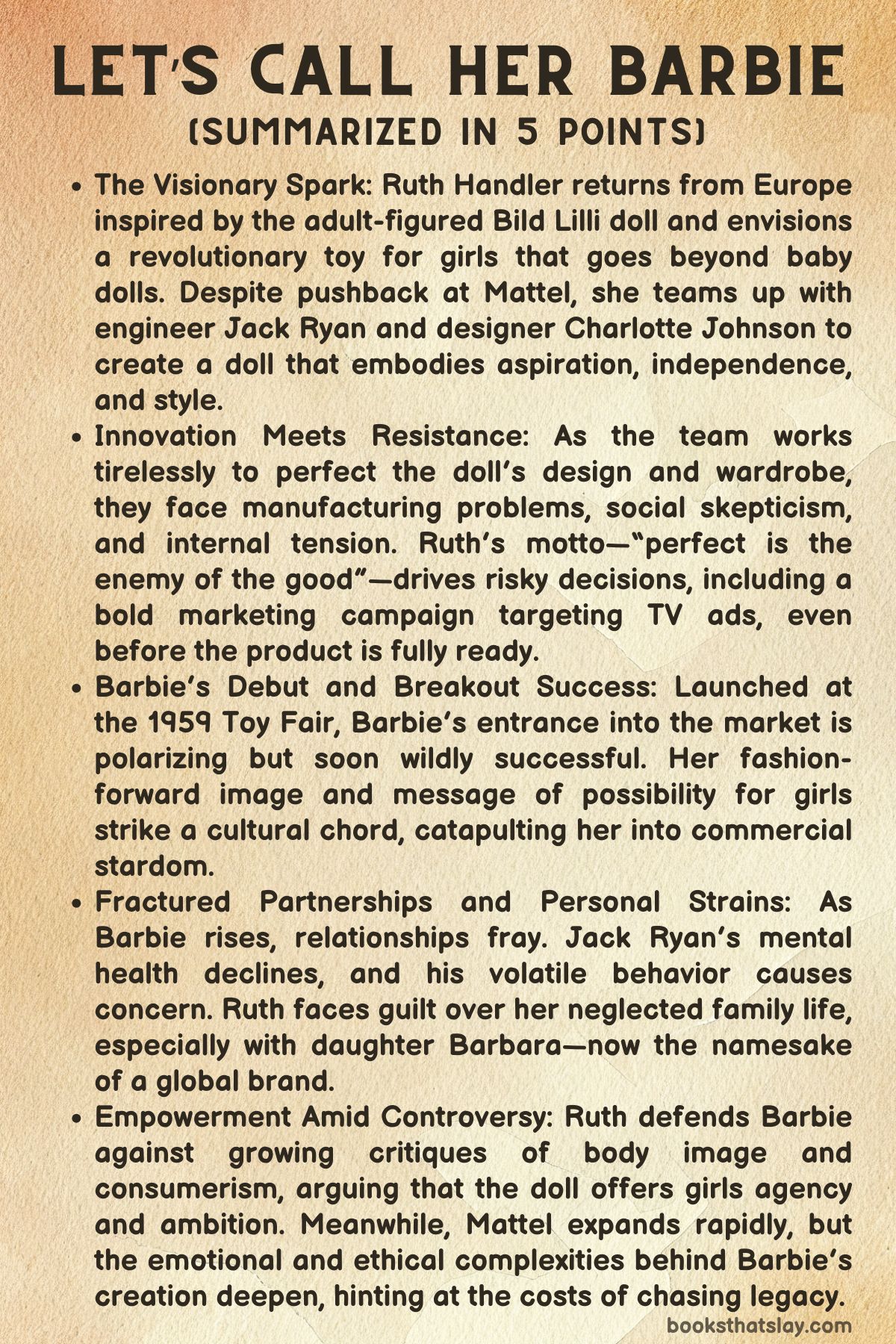

Let’s Call Her Barbie by Renee Rosen is a vivid and emotionally layered historical novel that fictionalizes the fascinating behind-the-scenes story of how one of the most iconic toys in the world—Barbie—was brought to life. At its heart is Ruth Handler, the ambitious and visionary businesswoman who co-founded Mattel and fought to reimagine the possibilities of girlhood through a doll that represented adulthood, independence, and aspiration.

Through the interwoven stories of Ruth, the engineer Jack Ryan, and designer Stevie Klein, the book explores the cost of creation, the complexity of innovation, and the personal toll exacted by ambition, perfectionism, and reinvention. It’s not just the story of a doll—it’s the story of the people who poured themselves into her.

Summary

Let’s Call Her Barbie begins with Ruth Handler returning from a trip to Europe, clutching a provocative German doll named Bild Lilli, a novelty adult figurine originally intended for men. Ruth sees beyond its risqué origins and recognizes its potential as a revolutionary toy for girls—a mature fashion doll that encourages imaginative play beyond baby dolls and homemaking.

She storms into a meeting of Mattel’s male engineers, disrupting their agenda with her bold idea. While they mock the doll’s overtly adult figure, Ruth sees a future symbol of female independence and ambition.

Among the skeptics is Jack Ryan, a brilliant but eccentric engineer whose need for recognition and flair for invention eventually draw him into Ruth’s orbit.

Despite early ridicule, Ruth persuades Jack to travel to Japan in search of manufacturers capable of producing the doll. The journey is fraught with cultural and logistical challenges, but Jack manages to secure a deal.

Meanwhile, Ruth recruits Charlotte Johnson, a financially struggling former model turned fashion designer, to create Barbie’s wardrobe. Though hesitant at first, Charlotte recognizes the creative opportunity, especially as Ruth positions the clothes—stylish, modern, interchangeable outfits—as the doll’s true money-maker.

As the project unfolds, Ruth, Jack, and Charlotte develop a working camaraderie, solving unprecedented design problems, from plastic hair and finger molds to telescopic joints and wardrobe linings. But personal tensions grow.

Ruth’s husband, Elliot Handler, also Mattel’s co-founder, becomes increasingly uneasy with Ruth’s fixation on Barbie, especially given the toll it takes on their marriage and children. Ruth’s own emotional wounds from a childhood marked by abandonment drive her to prove her worth and assert control over every aspect of Barbie’s creation.

Jack Ryan’s personal demons emerge too. Behind his energetic genius lies a troubled man, shaped by a cold upbringing, prone to manic behavior and sexual impulsivity.

He battles inner chaos while contributing massively to Barbie’s physical form. Despite his volatility, the team perseveres.

Their drive is relentless, their ambition united. Ruth’s unwavering belief that this doll will reshape cultural norms keeps them moving forward.

The doll, eventually named Barbie after Ruth’s daughter Barbara, becomes more than a product—it’s a manifestation of personal aspirations and emotional longing.

With Barbie’s launch on the horizon, the team expands. Stevie Klein, a former fashion student whose career derailed after personal setbacks, joins as a designer.

Initially insecure, Stevie soon demonstrates immense talent. Designing for Barbie proves demanding—every outfit must be precise, stylish, and miniature haute couture.

Stevie’s arrival brings new dynamics. She grows close to Jack, their relationship turning romantic and then unraveling, leaving behind a lingering tension.

Jack, wounded by Stevie’s independence, shifts his attention to Ginger, his plain but devoted assistant. He finances her makeover—diet pills, surgeries, wardrobe—to mold her into a Barbie-like figure, more as an exercise of control than affection.

Jack and Stevie continue working together professionally on the Barbie Dream House, a project sparked by Ruth’s desire to give Barbie her own home, not a playhouse with a kitchen but an emblem of independence. Their platonic collaboration rekindles mutual respect and creative synergy, even as Ginger hosts extravagant parties at Jack’s estate and reshapes herself into a plastic ideal.

Meanwhile, a new wave of female designers joins the team, and though rivalry surfaces, they gradually form a supportive network with Stevie as a guiding mentor. Together, they navigate Ruth’s exacting standards and push forward the Barbie brand.

Tensions mount with the rise of feminism. At a consciousness-raising session, Stevie hears harsh critiques of Barbie’s proportions and message.

Initially defensive, she starts to reflect—especially as she watches Ginger turn herself into a living replica of the doll. Ruth, however, pushes back.

Determined to preserve Barbie’s role as a figure of ambition rather than domesticity, she introduces characters like Skipper, Barbie’s younger sister, to expand the brand’s message.

Then comes betrayal. Jack, chasing recognition, falsely claims sole credit for creating Barbie during a television appearance.

Ruth is livid. The trust and collaboration they once shared collapses.

Though Jack continues contributing—designing Twist ’n Turn Barbie and Hot Wheels—his public behavior grows erratic, and his personal life spirals into alcohol, celebrity marriages, and self-sabotage. The once-gifted engineer becomes a cautionary figure of brilliance undone by ego and instability.

Mattel, too, starts to shift. The male-dominated leadership marginalizes women’s contributions.

Stevie, already disillusioned by tone-deaf releases like “Growing Up Skipper”—a doll that grows breasts when her arm is twisted—finds her creative voice stifled. She resigns, unwilling to compromise her artistic integrity, and is offered a prestigious new role by Bob Mackie, a famed designer, giving her the opportunity to rebuild her career on her terms.

Ruth’s trajectory crashes when Mattel is embroiled in a financial scandal involving misleading accounting tactics. She is ousted from her own company, investigated by the SEC, and humiliated.

Her health also declines following a mastectomy. But Ruth refuses to fade away.

Frustrated by the poor quality of breast prosthetics, she partners with Peyton Massey to design and market Nearly Me, a product aimed at restoring dignity to breast cancer survivors. She reinvents herself once more, not through a doll this time, but through a deeply personal innovation.

The final chapters of Let’s Call Her Barbie trace the downfall and resurgence of its core characters. Jack retreats into a tragic haze of excess and mental health struggles.

Stevie ascends to creative independence, free from compromise. Ruth, broken by scandal, finds redemption and meaning in Nearly Me, contributing to a different kind of empowerment.

The Mattel they helped build becomes bureaucratic and sterile, a reflection of what happens when commerce overtakes vision.

Barbie, however, remains—controversial, beloved, and iconic. She is both a product of her time and a symbol of evolution.

And through Ruth, Stevie, and Jack, the novel shows that invention is rarely clean. It is personal, painful, and often rooted in deep emotional needs.

The people behind Barbie may have broken under pressure, but they also left behind a legacy that transformed not just playtime, but how girls imagined their futures.

Characters

Ruth Handler

Ruth Handler is the indomitable force at the center of Lets Call Her Barbie, a woman whose vision, resilience, and contradictions shape the narrative as much as they shaped the real-world trajectory of Barbie. She is introduced as a woman returning from Switzerland with a radical idea: to revolutionize how girls imagine their futures through a doll that reflects womanhood rather than motherhood.

Her ambition is both her greatest asset and deepest source of internal conflict. Ruth believes fiercely in Barbie as a feminist symbol, yet she is often blind to the emotional cost of her relentless drive—on herself, her family, and her collaborators.

Her relationship with her daughter Barbara becomes strained, as Barbara sees Barbie not as a symbol of empowerment but as an unattainable ideal that overshadows her own identity. Ruth’s past—marked by abandonment and a compulsive need to prove her worth—fuels her refusal to give up or compromise.

Her eventual fall from grace during the SEC investigation and her resurrection through the creation of Nearly Me reflect a woman who refuses to be defined by failure. Even when ousted from Mattel, Ruth reinvents herself, channeling personal trauma into innovation once more.

Her journey encapsulates the complex interplay between maternal instincts, corporate ambition, and cultural legacy.

Jack Ryan

Jack Ryan emerges as a brilliant, tormented, and ultimately tragic figure. As the engineer behind Barbie’s iconic design, Jack contributes immeasurably to the doll’s success, bringing to life innovations such as telescoping joints and Saran hair.

Yet behind his creative prowess lies a man grappling with deep insecurities, psychological instability, and a desperate need for validation. His charm and charisma mask manic tendencies and a hypersexual nature that often complicate professional relationships.

His bond with Ruth is electric and grounded in mutual ambition, but his personal volatility and inflated ego threaten to derail his contributions. Jack’s descent accelerates after the public betrayal of Ruth, when he falsely claims full credit for Barbie.

The moment severs his most meaningful professional connection, and from there, Jack spirals into addiction, emotional volatility, and destructive behavior. His relationship with Ginger, whom he attempts to mold into a living Barbie, underscores his obsession with control and perfection—ironically mirroring the unrealistic standards Barbie herself would later be criticized for.

Ultimately, Jack’s downfall is a cautionary tale about brilliance unmoored from emotional stability, and how the pursuit of legacy can morph into self-destruction.

Stevie Klein

Stevie Klein is a narrative revelation—a character who begins as a vulnerable, aspiring designer and gradually becomes the moral and creative compass of the story. Initially unsure of her place in the high-stakes, high-pressure world of Mattel, Stevie is mentored by Charlotte and eventually finds her unique voice and design sensibility.

Her affair with Jack complicates her personal growth, but their eventual platonic collaboration on the Dream House marks a turning point—an evolution from romantic entanglement to creative partnership. Stevie’s growing awareness of Barbie’s cultural implications, especially after encountering feminist critiques, marks her ideological transformation.

She begins to question the very icon she helped shape, recognizing the doll’s duality as both a symbol of empowerment and a vehicle of unrealistic beauty standards. Her resignation from Mattel, in protest of increasingly regressive products, is an act of self-respect and creative integrity.

Her hiring by Bob Mackie signals her entry into a new phase of professional autonomy. Stevie’s arc is a powerful meditation on what it means to be an artist with a conscience in a commercial world, and her evolution mirrors broader societal shifts around feminism, authenticity, and identity.

Elliot Handler

Elliot Handler is often the quiet ballast to Ruth’s tempestuous ambition. As co-founder of Mattel and Ruth’s husband, Elliot occupies a complicated emotional space.

He is pragmatic, supportive, and often the voice of reason, such as when he suggests naming the doll Barbie—a moment of clarity amid chaos. Yet he also struggles with feeling sidelined, both professionally and personally.

The growing dominance of Ruth’s vision and the emotional demands of the Barbie project create tension in their marriage, as Elliot perceives his wife slipping away into her ambitions. While less flamboyant than Ruth or Jack, Elliot represents the silent cost of success—how even well-meaning partnerships can become strained under the weight of innovation and fame.

Ginger

Ginger begins as a peripheral assistant and evolves into a symbol of the unintended consequences of Barbie’s influence. Deeply insecure, she becomes entangled with Jack, who exploits her vulnerability and sculpts her appearance to mirror Barbie’s aesthetic.

Though she briefly basks in the attention and glamour of hosting parties at the Castle, her transformation is ultimately hollow, rooted not in self-love but in external validation. Ginger’s narrative parallels the critical discourse around Barbie’s impact on women’s self-image.

Her efforts to become Barbie-like expose the doll’s darker side—not as Ruth intended it, but as society often interprets it. Her story underscores the blurred line between inspiration and distortion, between fantasy and identity loss.

Charlotte Johnson

Charlotte Johnson, the fashion designer recruited by Ruth, serves as the creative architect of Barbie’s haute couture world. Practical, talented, and initially skeptical, Charlotte brings a level of sophistication and craftsmanship to Barbie’s wardrobe, seeing it not as play but as art.

Her designs elevate Barbie beyond novelty, grounding her in a believable and aspirational aesthetic. She acts as a mentor to Stevie and is instrumental in defining Barbie’s fashion legacy.

Though less emotionally volatile than other characters, Charlotte’s presence is crucial—a steadying, pragmatic influence that turns vision into tangible reality.

These characters, each richly drawn and deeply human, form the emotional and ideological spine of Lets Call Her Barbie, transforming a toy into a cultural milestone and exposing the personal costs behind its glittering success.

Themes

Female Ambition and the Price of Vision

Ruth Handler’s pursuit of Barbie becomes a compelling study in ambition shaped by gendered expectations. In a postwar America that still viewed women as homemakers, Ruth dares to imagine and create a toy that breaks from tradition.

Her concept of a fashion doll, meant to allow girls to envision adult careers and independence, challenges both market assumptions and cultural norms. This ambition, however, exacts a steep personal price.

Ruth’s tireless drive isolates her from her family, strains her marriage, and creates friction in her professional environment, particularly with her husband Elliot, who fears losing control over both the company and his wife. Her own daughter, Barbara, is alienated by Barbie’s idealized image, leading to emotional disconnect.

Ruth’s vision is rooted not only in innovation but also in an unresolved childhood need for validation after being emotionally abandoned and raised to believe that usefulness equals worth. Her pursuit of Barbie reflects a deeper desire to shape a world that recognizes and rewards female ingenuity.

Yet, as she rises within Mattel, she is often vilified for the same traits that are praised in male executives—toughness, relentlessness, vision. The emotional labor of constantly proving herself, of transforming guilt into productivity, underscores the toll such ambition takes on women in leadership.

Her eventual downfall in the form of a corporate scandal reflects not just an ethical lapse but the fragility of women’s power in male-dominated spaces. Still, her resurrection through Nearly Me shows that even in ruin, ambition can lead to transformation and new forms of influence.

Masculinity, Insecurity, and Self-Destruction

Jack Ryan’s arc reveals how masculinity, when tethered to ego and performance, becomes a fragile construct vulnerable to collapse. Jack is brilliant, charismatic, and essential to Barbie’s physical design, yet his self-worth is inextricably linked to recognition and sexual validation.

Despite his engineering genius, he harbors deep insecurity—about his reading disability, his upbringing, and his perceived expendability. He masks these wounds with bravado and excess, indulging in affairs, parties, and ultimately, substance abuse.

Jack’s flirtations with women at work, particularly Stevie, are not just romantic overtures but assertions of dominance and worth. His eventual claim on national television that he alone created Barbie is not just betrayal, but a desperate attempt to be seen and remembered in a world that increasingly sidelines him.

As he spirals into addiction and erratic behavior, Jack becomes a cautionary figure, emblematic of how traditional masculinity can be both performative and corrosive. Even his relationships are shaped by his need to fix or mold others—he transforms Ginger physically, not out of love but out of a need to project control.

Jack’s decline, hastened by a resistance to mental health treatment, exposes how deeply men may fear vulnerability. His collapse is not merely personal; it signals a broader indictment of a culture that equates masculinity with dominance and success, yet offers little room for emotional honesty or failure.

Reinvention as a Mode of Survival

Throughout Lets Call Her Barbie, reinvention is portrayed not as luxury but as necessity. Ruth reinvents herself multiple times—from a neglected child to a tenacious entrepreneur, from disgraced executive to creator of life-changing prosthetics.

Her resilience is rooted in adaptability, in her ability to find purpose beyond one failure or identity. Similarly, Stevie evolves from a hesitant assistant to a confident designer, and finally, to an autonomous creative who walks away from a stifling environment.

Her journey illustrates the discomfort and eventual liberation of stepping into one’s power. Even Jack, despite his downfall, constantly reinvents the physical and aesthetic form of Barbie, contributing to innovations like Twist ’n Turn Barbie and Hot Wheels.

Reinvention is also literalized through the doll itself, whose changing looks, roles, and accessories mirror societal shifts. Yet the most poignant examples of reinvention are those rooted in pain.

Ginger reshapes herself into Barbie’s image in a misguided bid for love and affirmation, revealing the dangers of transforming oneself to meet someone else’s fantasy. The act of reinvention, then, is not inherently redemptive; it depends on agency, intent, and self-awareness.

While for Ruth and Stevie, reinvention becomes empowerment, for Jack and Ginger, it becomes a mask that accelerates personal erosion. The narrative makes clear that in a world that is constantly changing—socially, culturally, and personally—those who survive are those who adapt, but the cost and outcome of that adaptation varies widely.

Feminism, Identity, and Representation

As Barbie evolves, so does the conversation about what she represents. Initially conceived as a figure of aspiration, a grown-up doll that allows girls to imagine independence and ambition, Barbie is soon caught in a cultural crossfire.

Feminist critiques highlight her unrealistic proportions, narrow beauty standards, and implied sexualization. These critiques are not dismissed by the narrative; instead, they become a mirror for the creators themselves.

Stevie, once proud of designing for Barbie, finds herself questioning the broader implications of her work, especially when juxtaposed against Ginger’s transformation into a living Barbie. Ruth, meanwhile, resists the idea that Barbie must be domesticated or toned down, insisting on her as a symbol of possibility.

The tension between empowerment and objectification runs throughout the novel, particularly as the feminist movement gains momentum in the 1960s. The creation of Skipper and other characters reflects an attempt to diversify Barbie’s world, to show that women can be many things—sisters, professionals, dreamers.

Still, the company’s male leadership often undercuts these ambitions with tone-deaf products like Growing Up Skipper, revealing the limits of representation in a patriarchal corporate structure. The novel does not offer easy answers but rather invites a nuanced consideration of what it means to represent women authentically in a product intended for play.

Barbie becomes a battleground for identity politics, shaped by those who love her, resent her, imitate her, and try to redefine her.

Creativity, Collaboration, and Corporate Control

The early days of Barbie’s creation are fueled by passion, creativity, and unlikely alliances. Ruth, Jack, and Charlotte form a dynamic, if sometimes volatile, team united by a belief in something new.

Their late nights and trial-and-error process reflect a kind of artistic alchemy rarely seen in large companies. As the project grows, more players join—Stevie, a new generation of designers, and even Ginger in her own performative way.

The creative process is messy, intimate, and deeply personal. But as Mattel expands, the corporate machinery begins to erode that spirit.

Risk-taking gives way to bureaucracy, innovation is replaced by replication, and creative voices—especially those of women—are silenced or dismissed. The betrayal Ruth feels when Jack publicly claims credit is not just personal but symbolic of how corporate structures often erase collaborative contributions in favor of singular, male-dominated narratives.

Stevie’s eventual departure and the company’s descent into tone-deaf product launches underline the loss of creative integrity. At its best, the Barbie team represents the potential of collaboration across gender, skill, and temperament.

At its worst, Mattel becomes a cautionary tale of what happens when creativity is sacrificed to maintain dominance in a profit-driven system. The story honors the labor and vision behind Barbie but also critiques the forces that threaten to strip those efforts of meaning.

In doing so, it affirms that true innovation requires not just brilliance, but the space, respect, and protection to thrive.