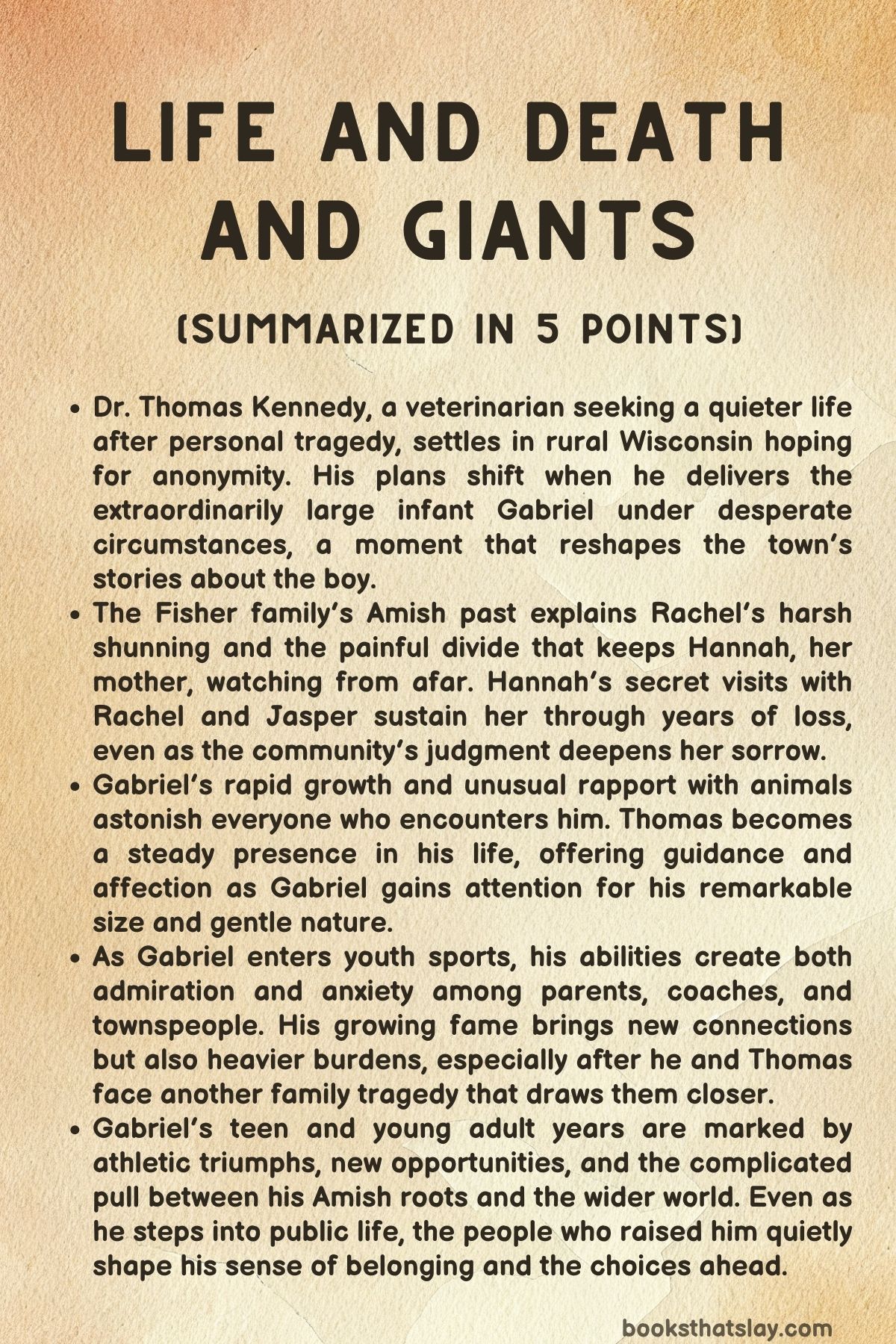

Life and Death and Giants Summary, Characters and Themes

Life and Death and Giants, by Ron Rindo, is a novel about a quiet Wisconsin town transformed by the extraordinary life of an extraordinary boy. It follows Dr. Thomas Kennedy, a grief-stricken veterinarian seeking solitude, and Gabriel Fisher, a child born under astonishing circumstances whose size, strength, and sensitivity reshape the lives around him.

Across decades, the story explores community, family, faith, trauma, and the burden of being different. Told through multiple voices—Amish and English alike—it reveals how one life can unsettle old beliefs while offering unexpected hope. The novel blends rural hardship with moments of wonder, ultimately tracing the arc of a giant in body and spirit.

Summary

Lakota, Wisconsin is a declining rural town where privacy and hard living define daily life. Into this community arrives Dr. Thomas Kennedy, a veterinarian retreating from the scrutiny that followed his wife Angela’s suicide. Hoping for quiet work among farmers, he settles by the Mecan River.

That peace ends when seventeen-year-old Jasper Fisher arrives one morning with his mother, Rachel, unconscious and swollen from a prolonged labor she refused to treat for religious reasons. Jasper begs Thomas not to send her to the hospital but to save the babies he believes she carries.

Thomas reluctantly agrees and discovers a single, impossibly large fetus. Using veterinary tools and techniques, he enlarges the birth canal and pulls an eighteen-pound, twenty-seven-inch boy into the world.

Minutes later Rachel dies, and animals across the valley cry out as Gabriel takes his first breaths. Rumors spread, and the story of his birth grows into legend.

The narrative then turns to Hannah Fisher, Rachel’s mother, who recounts the family’s Amish life and the harsh upbringing she endured under her father Absalom Yoder. Hannah’s early married years with Josiah are steady but marked by loss; their first child dies shortly after birth.

Rachel’s arrival brings joy, yet Josiah later becomes infertile after contracting mumps. Rachel grows into a strikingly beautiful girl whose looks draw unwanted attention within the conservative community.

At sixteen she is baptized, but everything changes when she becomes pregnant at seventeen and refuses to reveal the father. The church imposes the strictest form of shunning.

With nowhere to go, Rachel moves across the river to live with the Widow Charlotte. Hannah secretly watches for her, eventually meeting her across the river at night.

Rachel raises her son Jasper with dignity despite loneliness.

Charlotte leaves her property to Rachel, giving her a small measure of stability. Years later Rachel becomes pregnant again and insists the child is a blessing.

Her body expands rapidly until she becomes housebound. Hannah watches helplessly as Rachel declines.

Before she can reach her, Rachel dies giving birth to Gabriel, the same child Thomas delivered.

After the small funeral, Thomas checks on Jasper and the newborn. Jasper tries to feed Gabriel but struggles until a wandering goat appears with an overfull udder; he milks her and raises Gabriel on goat’s milk.

Thomas becomes a regular presence, bringing food, clothing, and help. Gabriel grows at incredible speed and displays a remarkable gentleness with animals.

Chickens rest calmly on him, cats curl into his arms, and even skittish sheep settle in his presence. Thomas sees in Gabriel a reflection of his own childhood love for animals and begins taking him along on weekend veterinary calls.

As word of Gabriel spreads, Billy Walton, the local tavern owner and youth baseball organizer, becomes aware of the enormous five-year-old. Thomas enrolls Gabriel in T-ball, where his power forces rule changes.

Even with a lightweight bat he hits towering home runs, finishing with an astonishing batting record. The region takes notice, and stories circulate about the giant son of Rachel Fisher.

Hannah, still grieving, watches from afar. She reads scripture and her late mother’s book of Emily Dickinson poems, annotated in the margins, slowly finding strength.

She longs to see Gabriel, but Jasper rejects contact with the Amish community that shunned his mother. Eventually she secretly watches Gabriel play baseball from a buggy parked beyond the field.

Seeing him tower over other children and strike a ball beyond the far fence overwhelms her; she sees Rachel in his face.

When Hannah’s beloved goat becomes fatally ill, Thomas arrives with Gabriel. The boy comforts the dying animal and then embraces Hannah, a moment that pierces her grief.

After Thomas leaves, she performs the euthanasia herself, burying the goat in the rain while thinking only of Gabriel’s kindness.

As Gabriel grows older, his athletic achievements accelerate. At six he moves to the minor league; at seven he is banned after a line drive breaks another child’s hand.

At nine he is six foot four and moves into major league youth baseball, where he hits fifty home runs in a season filled with crowds and spectacle. Meanwhile Jasper falls behind on taxes and begins working at Absalom Yoder’s sawmill.

Gabriel struggles in school, bullied for his size. Thomas supplements his education with books from his mother’s library.

He takes Gabriel to Milwaukee to visit his dementia-stricken mother, who responds warmly to Gabriel in a way that mystifies Thomas. On their way home through a storm they find Jasper dead by suicide in the barn.

Thomas shields Gabriel and brings him through the rain to Hannah and Josiah’s home. They welcome the boy and prepare Rachel’s old room for him.

Hannah sings him to sleep as dawn approaches.

The story later moves forward to Gabriel’s college years. He becomes a monumental football star for Wisconsin, anchoring both lines.

During a major game against Ohio State, a pileup crushes his right knee, causing catastrophic damage that leads to amputation above the knee. The injury devastates the state and everyone who loves him.

Hannah suffers intense spiritual turmoil, wrestling with faith and loss, but finds brief clarity in her mother’s old poetry book.

With help from a social worker, the Fishers prepare their Amish home for Gabriel’s return. When he arrives—immense, tattooed, bearded, and grieving—he tries to adapt but founders in the electricity-free world.

Hannah eventually realizes he cannot thrive there. She asks Thomas to take him in.

Thomas builds a space for him, adjusts his home and vehicle, and supports him through physical therapy. Gabriel assists with veterinary work and finds comfort among animals, yet admits he misses the challenge of sports.

A London wrestling company offers him a contract. He accepts, launching a spectacular career as “Anakim, the Amish Giant.

” He becomes a global phenomenon, performing feats of strength and creating dramatic storylines in arenas around the world. Fame brings both joy and isolation.

Hannah, Thomas, and the town follow his rise from afar, and eventually Hannah agrees to see one of his matches in Chicago.

Eventually Gabriel returns home with devastating news: an inoperable brain tumor has left him blind and dying. He spends his final months at Thomas’s farmhouse, cared for by Thomas and Hannah.

Slowly he allows Hannah to guide him on daily walks, during which he recalls his travels and the loneliness beneath his fame. Hannah eventually reveals the painful truth of his parentage: Gabriel and Hannah share a father—Absalom Yoder, a violent and cruel man.

Gabriel cares more about Hannah’s suffering than his own shock.

As his condition worsens, neighbors and former mentors visit. Paparazzi descend but are driven out by the community, organized by Billy Walton and other locals.

When Gabriel becomes bedridden, an English nurse joins the household, and Josiah builds equipment to accommodate his immense size. Amish women arrive in shifts to bathe him, feed him, pray over him, and provide comfort.

Gabriel’s former girlfriend, Bella Alvarez, arrives with their two-year-old son, Raphael. Her presence lifts him; he holds his child and savors moments of peace.

As his pain increases, he returns to heavy morphine, cared for jointly by Bella and the Amish women.

On August 2, just before dawn, Gabriel’s breathing changes. A luminous gathering of animals fills the yard: birds, livestock, wild creatures, and clouds of insects, culminating in a storm of fireflies that surround his body with blinding light.

In this light, Gabriel dies peacefully.

The community holds a massive private funeral in a hidden field, attended by hundreds—Amish families, townspeople, former teammates, and friends. After hymns and spoken tributes, Gabriel’s enormous oak casket is carried by wagon and buried beside his mother and brother.

In the aftermath, Hannah reflects on suffering, faith, and the unexpected gifts Gabriel brought into her life. She returns to her Amish duties and embraces her new role in Raphael’s life.

Thomas, devastated by Gabriel’s death and unable to remain near Hannah without deep emotional pain, sells his home and leaves Wisconsin for a solitary cabin in Montana. As he drives west, he feels both sorrow and the sense of a new beginning, even at seventy-one.

Characters

Dr. Thomas Kennedy

Thomas Kennedy is a man shaped by grief, guilt, and an aching desire for redemption. A veterinarian fleeing the emotional wreckage of his wife Angela’s suicide and the pain of multiple miscarriages, he arrives in Lakota hoping for anonymity and calm but finds instead a new purpose through his bond with Gabriel.

With animals he is skilled, empathetic, and instinctively protective; with people he is cautious, wary, and a little broken. His accidental role in Gabriel’s miraculous birth ties him irrevocably to the Fisher family, and over the years he becomes a surrogate father to both Jasper and Gabriel, offering them stability, education, and emotional safety that he cannot give himself.

His tenderness with the boy reveals a quiet longing—Thomas wants to nurture, to save, to be needed. Later in life, when he becomes Gabriel’s caretaker during his final illness, Thomas is both humbled and enriched by the experience, facing mortality with a gentleness learned from the very child he once delivered.

His departure at the end of the story, retreating into solitude in Montana, reflects a man who has given everything he had to give and must now rebuild his own identity in the wake of heartbreak and love.

Hannah Fisher

Hannah is the emotional and moral core of the novel, a woman molded by Amish tradition, severe childhood trauma, and a lifetime of quiet endurance. The shunning of her daughter Rachel leaves a wound that never fully closes, and the secrecy of her nightly visits to Rachel reveals both the constraints of her world and the rebellious strength of her maternal love.

Hannah’s deep faith is constantly tested—first by Rachel’s ostracization, then by the mysterious nature of Gabriel’s birth, and later by the tragedies that threaten to rip the remaining pieces of her family apart. Yet she remains resolutely compassionate, her love expressed through acts of service, domestic warmth, spiritual contemplation, and a steadfast refusal to abandon those she cares for.

Her relationship with Gabriel, from their first embrace beside the dying goat Magdalene to their long walks during his final months, becomes a redemptive journey for her, transforming her understanding of suffering and grace. Her acceptance of Bella and Raphael into her life reveals a generosity that transcends doctrine, and by the novel’s end Hannah emerges as a woman whose faith has deepened not through obedience but through profound, lived experience.

Gabriel Fisher

Gabriel is the extraordinary center of the story, a giant in both body and spirit whose life is marked by mythic wonder and crushing vulnerability. Born enormous under impossible circumstances, he becomes a figure of fascination, feared and adored by animals and humans alike.

Yet despite his physical dominance, Gabriel is gentle, emotionally perceptive, and deeply lonely. Growing up without his mother and later without Jasper, he clings to Thomas, the man who raises him into kindness as much as strength.

As a child, Gabriel displays uncanny empathy, calming distressed animals and offering comfort without words. As an athlete, he becomes a near-supernatural force, his baseball and football feats drawing crowds and creating legends.

And as a wrestler, he embraces spectacle while yearning for genuine connection. His catastrophic injury and eventual terminal illness reveal the child within the giant—a boy who once bottle-fed goat’s milk, slept in Rachel’s old room, and walked fields with his grandmother.

Even in his final days, blind and weak, Gabriel exudes a presence that draws the living world to him. His death is depicted not as an end but as a transcendent return to the natural order, confirming him as a figure who reshaped everyone he encountered.

Rachel Fisher

Rachel is a symbol of defiance, suffering, and tragic beauty. Growing up under strict Amish rules, she is both the joy of her mother Hannah’s life and the subject of unwanted attention because of her beauty.

Her faith is sincere but deeply personal, and when she becomes pregnant at seventeen and refuses to reveal the father’s identity, she is cast out under streng meidung. Her exile reveals the cruelty of rigid doctrine and the loneliness of a girl who will not betray her convictions even at great personal cost.

Rachel’s first child, Jasper, becomes her anchor, and the years she spends raising him across the river from her parents are both isolating and resilient. Her second pregnancy is shrouded in mystery and rapid physical decline, culminating in her death during Gabriel’s monstrous birth.

The stories the community later tells about her and Gabriel become legendary, but beneath the mythology lies a young mother who died believing her children were gifts from God. Rachel’s absence haunts nearly every character, especially Hannah and Gabriel, whose lives carry the imprint of her loss.

Jasper Fisher

Jasper is a boy forced into adulthood too early, shaped by abandonment, religious shunning, and the heavy responsibility of caring for his mother and later Gabriel. His childhood is marked by hardship—raised by an ostracized mother, cut off from family support, and burdened with labor beyond his years.

After Rachel’s death, Jasper becomes both brother and parent to Gabriel, feeding him goat’s milk, nurturing him with fierce loyalty, and keeping him safe through the chaos of rumors and judgment. His relationship with Thomas gradually evolves from suspicion to deep trust as Thomas becomes an indispensable presence in their lives.

Jasper’s later struggles—financial pressure, the grueling job at Absalom Yoder’s sawmill, and the emotional toll of isolation—reveal the fragility beneath his stoic exterior. His suicide is one of the novel’s most devastating moments, leaving Gabriel shattered and Thomas guilt-ridden.

Jasper’s life is a portrait of love weighed down by unbearable burden, and his absence reverberates through Gabriel’s entire story.

Josiah Fisher

Josiah is a man caught between devotion and rigidity, faith and fear. Once a loving husband and hopeful father, his infertility after mumps shapes much of his identity, creating quiet insecurities that color his relationship with Rachel and later with Gabriel.

Josiah initially upholds the Amish community’s harsh treatment of Rachel, but his grief after her death softens him, revealing a man who mourns deeply but struggles to express it. His unease with Gabriel’s extraordinary nature reflects both superstition and unresolved paternal doubt.

Still, when Jasper dies, Josiah opens his home to the boy Gabriel once again becomes, demonstrating a capacity for compassion that rises above his fears. Throughout the novel, Josiah represents the complexities of faith lived in a world where divine mysteries refuse to obey human rules.

Billy Walton

Billy is the community’s flawed yet big-hearted storyteller, a man who drinks too much, parents too little, and gives too freely to the children he coaches in baseball. His tavern is the unofficial town center, and his voice provides an earthy, irreverent counterpoint to the novel’s more spiritual and tragic perspectives.

Billy loves the spectacle of Gabriel’s athletic success but also recognizes the humanity behind it, defending the boy against gossip and unfair accusations. He becomes a fierce protector of Gabriel in adulthood, helping to drive away paparazzi and honoring him with a heartfelt eulogy.

Billy’s character blends humor, nostalgia, and regret, and his loyalty to Gabriel reveals a capacity for goodness that transcends his shortcomings.

Absalom Yoder

Absalom is the shadow looming over Hannah, Rachel, and ultimately Gabriel. A man steeped in violence, cruelty, and oppressive piety, he represents the darkest expression of patriarchal religious authority.

His abuse of Hannah defines her childhood and shapes her marriage, motherhood, and faith. The eventual, horrifying revelation that he fathered both Rachel’s son Jasper and Hannah’s grandson Gabriel confirms the novel’s deepest truths about generational trauma and secrecy.

Absalom never receives redemption; instead, his legacy is carried forward through the suffering he caused and the strength his victims ultimately display. His presence is a quiet indictment of unchecked power within closed communities.

Bella Alvarez

Bella offers Gabriel something the rest of the world cannot: unconditional love without awe or fear. Their relationship, formed during Gabriel’s college years, is passionate and steady despite being overshadowed by Gabriel’s fame and eventual withdrawal.

Her reappearance at the end of the novel with their son Raphael provides Gabriel a final, radiant source of meaning and peace. Bella’s willingness to care for Gabriel in his last days alongside the Amish women reflects her strength, loyalty, and grace.

She bridges Gabriel’s worlds—modern and Amish, public and private—and becomes the vessel through which his legacy continues.

Raphael

Raphael, Gabriel’s young son, appears late in the story but embodies hope, renewal, and continuity. His presence brings Gabriel a joy he thought forever lost, granting him purpose during his final weeks.

Through Raphael, the Fisher family begins a new chapter—one unmarred by the violence and secrecy of the past. He symbolizes healing, lineage, and a life that grows from tragedy into possibility.

Dorothy Kennedy

Dorothy, Thomas’s mother, appears only briefly but leaves an emotional imprint on both Thomas and Gabriel. Struggling with dementia, she nevertheless connects with Gabriel in a profound and inexplicable way, recognizing in him something innocent and wondrous.

Her library, her memories, and her quiet presence reveal parts of Thomas that he rarely shows the world.

Themes

Faith, Doubt, and the Burden of Spiritual Authority

Faith in Life and Death and Giants operates as both a source of strength and a force of destruction, shaping entire lives through unquestioned authority and inherited tradition. The Amish world surrounding Rachel and Hannah is defined by its insistence on obedience, separation, and the belief that suffering is both expected and redemptive.

Yet the novel constantly exposes the tension between private conviction and institutional power. Hannah experiences faith as a quiet companion—a set of rituals, scriptures, and memories that anchor her—but she also carries lifelong wounds inflicted by men who wielded religious doctrine as a weapon.

Absalom Yoder embodies this distortion: a man who uses scripture to justify violence, silence dissent, and enforce purity. His righteousness is fear masquerading as order, and his dominance shapes generations.

Rachel’s shunning reveals how a faith community can abandon compassion when doctrine becomes more important than people. Her pregnancy, met not with mercy but condemnation, exposes an upright society that refuses to look inward at its own hypocrisy.

Later, Hannah’s secret readings of Emily Dickinson show a woman awakening to a different kind of spirituality—one rooted in wonder, questions, and personal reflection rather than decrees. Gabriel’s life further complicates these boundaries.

His gentle power, his connection with animals, and the strange radiance surrounding his birth and death evoke a spiritual presence that defies Amish certainty and English skepticism alike. Faith becomes something felt rather than imposed.

Through Hannah, Thomas, and eventually Gabriel himself, belief is shown as a lifelong conversation rather than a rigid rulebook—a struggle to reconcile love and loss, mystery and suffering, discipline and grace.

The Cost of Isolation and the Human Need for Connection

Isolation shapes nearly every character long before it claims their futures. Thomas seeks Lakota as a refuge from grief, imagining solitude will dull the memory of Angela’s suicide, yet the silence of the Mecan River only sharpens his loneliness until Gabriel enters his life.

Rachel’s expulsion from her community turns separation into a living death, and her long decline becomes a portrait of what happens when a society enforces distance as punishment. Jasper inherits that isolation, growing up on the margins of two worlds—Amish and English—belonging fully to neither.

Even Gabriel, who is celebrated for his size and power, experiences isolation as a constant shadow. His body sets him apart from other children, coaches, fans, and finally from an entire nation that watches him rise and fall.

The more legendary his image becomes, the more hollow his private life grows. Fame brings crowds but not closeness.

Yet the novel also shows how connection rescues those lost to solitude. Hannah, burdened by decades of silence, finds light again when Gabriel wraps his arms around her during Magdalene’s death.

Thomas discovers a sense of purpose after years of emotional withdrawal when Gabriel rides with him on veterinary visits. And when Gabriel returns home blind and dying, isolation threatens to overwhelm everyone, but the Amish women—steady, prayerful, unpretentious—arrive in shifts to erase loneliness through physical presence.

This theme reveals that human beings survive not through independence but through shared burdens, meals, prayers, and small acts of care. The novel argues that isolation may wound, but connection—earned, hesitant, or imperfect—is what allows healing to begin.

Generational Trauma and the Long Reach of Violence

The shadow of Absalom Yoder stretches through the novel like a cold wind, shaping the lives of his descendants long after he has aged into infirmity. His cruelty, justified through religious authority, becomes a generational weight that Hannah carries into adulthood.

Her childhood, marked by fear and obedience, teaches her to accept suffering as a natural condition. Rachel inherits the consequences in subtler ways: secrecy, shame, a belief that her body and desires exist under constant judgment.

When she refuses to reveal the father of her child, the community sees only rebellion, not the legacy of silence and coercion she has internalized. Gabriel’s very existence is bound to this history, and his later discovery that he shares a father with Hannah forces him to confront the reality that his life began in violence.

Yet the novel avoids turning trauma into destiny. Instead, it shows how characters fight to reshape the story they were born into.

Hannah breaks the cycle through small but radical acts—meeting Rachel in secret, embracing Gabriel, extending compassion where she once feared reprisal. Gabriel refuses the bitterness that might have defined him; he channels his strength into kindness toward animals, playfulness with children, and a gentle curiosity about the world.

Even Thomas, an outsider, becomes a witness to the ways trauma mutates across generations and offers steadiness where others have faltered. This theme reveals that while violence leaves marks that echo through families, healing is equally capable of passing from one generation to the next.

Gabriel’s final moments—surrounded by music, fireflies, and community—become a symbolic release from the history that tried to shape him.

Bodies, Monstrosity, and the Burden of Being Different

Gabriel’s body dominates the story from the moment he is pulled into the world. Enormous at birth, towering by childhood, and colossal in adulthood, he lives constantly under the gaze of others—admiration, fear, curiosity, or suspicion.

The community’s reaction oscillates between awe and unease, as though his size signals something unnatural. His gentleness undermines these fears, but the tension persists: every playground, baseball field, and stadium becomes a stage where his body is scrutinized.

The novel questions what society labels monstrous and what it celebrates. When Gabriel hits baseballs into distant fields, children panic, and parents accuse him of endangering others.

Yet when he crushes opponents on the football field, the state cheers and corporations build brands around his body. Both responses reduce him to spectacle rather than person.

After his devastating injury, the public’s fascination transforms again, making his suffering part of a national narrative he never agreed to. The amputation brings a new form of physical difference, forcing him to navigate a world built for smaller, faster, more “normal” bodies.

His blindness later deepens this divide, confronting him with the fragility hidden beneath his strength. Through this arc, the story suggests that monstrosity is not inherent in the body but in the interpretations imposed upon it.

Gabriel redefines his own physicality by offering comfort to animals, working alongside Thomas, wrestling with theatrical flair, and finally accepting care with humility. His body becomes a vessel not of threat but of tenderness and wonder.

The novel transforms what might have been a grotesque spectacle into a meditation on human dignity, vulnerability, and the quiet heroism of carrying a body that others cannot understand.

Community, Redemption, and the Shifting Shape of Home

Lakota begins as a town marked by economic decline and cultural division, but as Gabriel’s life unfolds, the community gradually reveals its capacity for redemption. The Amish and English worlds that appear rigidly separated start to bleed into each other through acts of necessity, empathy, and grief.

Thomas becomes a bridge between them, moving from farm to farm, offering veterinary help and quiet companionship. Billy Walton, rough-edged and imperfect, becomes a protector not only of Gabriel but of the whole town when the paparazzi arrive.

Even those who once shunned Rachel eventually gather to care for her grandson in his final days. Redemption emerges not in grand gestures but in accumulated moments: Abiah accompanying Hannah to a hidden baseball game; Josiah building ramps and equipment after decades of emotional distance; Amish women sitting through the night to keep Gabriel clean and warm; townspeople forming roadblocks to shield him from exploitation.

Home shifts for every character. For Hannah, home becomes a place where forbidden books are read in darkness and where a dying grandson can be held as he slips away.

For Thomas, home evolves from a self-imposed exile into a place of purpose, then into a space he must leave after Gabriel’s death. For Gabriel, home is both the place he returns to and the place he outgrows—a source of belonging and a reminder of limitations.

The novel suggests that home is not a static location but a living relationship sustained by care. Redemption becomes possible when community stops enforcing boundaries and begins to share burdens, creating a collective home where even the most wounded can find rest.

Mortality, Legacy, and the Search for Meaning

Death shapes the novel from its opening pages, yet it never appears as final ruin. Rachel’s death marks the beginning of Gabriel’s legend; Jasper’s death forces Gabriel into the care of grandparents who become the anchors of his later life.

Angela’s suicide sends Thomas on the path that ultimately brings him to Gabriel. Each loss reshapes the living, compelling them to confront what remains meaningful.

Gabriel’s final illness becomes the most profound exploration of mortality in the story. Blind, weakened, and stripped of the physical strength that once defined him, he must reconstruct his sense of self through memory, storytelling, and the love that surrounds him.

He shares his travels with Hannah, discovering that his most enduring legacy is not measured in trophies or victories but in the people who cared for him and the child he leaves behind. His final moments—animals gathering, fireflies rising, hymns echoing from the yard—shift death from tragedy to transformation.

For Hannah, mortality becomes a lens through which she reevaluates her faith, her suffering, and the unexpected blessings that entered her life through Gabriel. For Thomas, Gabriel’s death forces him to release the life he built in Wisconsin and seek renewal elsewhere.

The novel suggests that meaning is found not in avoiding death but in shaping a legacy of tenderness, courage, and connection. Gabriel’s life, brief and extraordinary, becomes a testament to the idea that mortality does not diminish a person’s impact; it illuminates it.

Through him, the community discovers the possibility of grace even in sorrow, and the story itself becomes an argument that lives touched by love continue to echo long after the body fails.