Life In The Iron Mills Summary, Characters and Themes

“Life in the Iron Mills” is a short story by Rebecca Harding Davis, published in 1861.

It’s a stark portrayal of the grim realities faced by workers in 19th-century American factories. The story centers around Hugh Wolfe, a mill worker with artistic talent trapped in a life of poverty and despair. Davis uses vivid imagery and unflinching realism to expose the dehumanizing conditions of industrial labor and the crushing weight of social inequality, sparking a conversation about workers’ rights that remains relevant today.

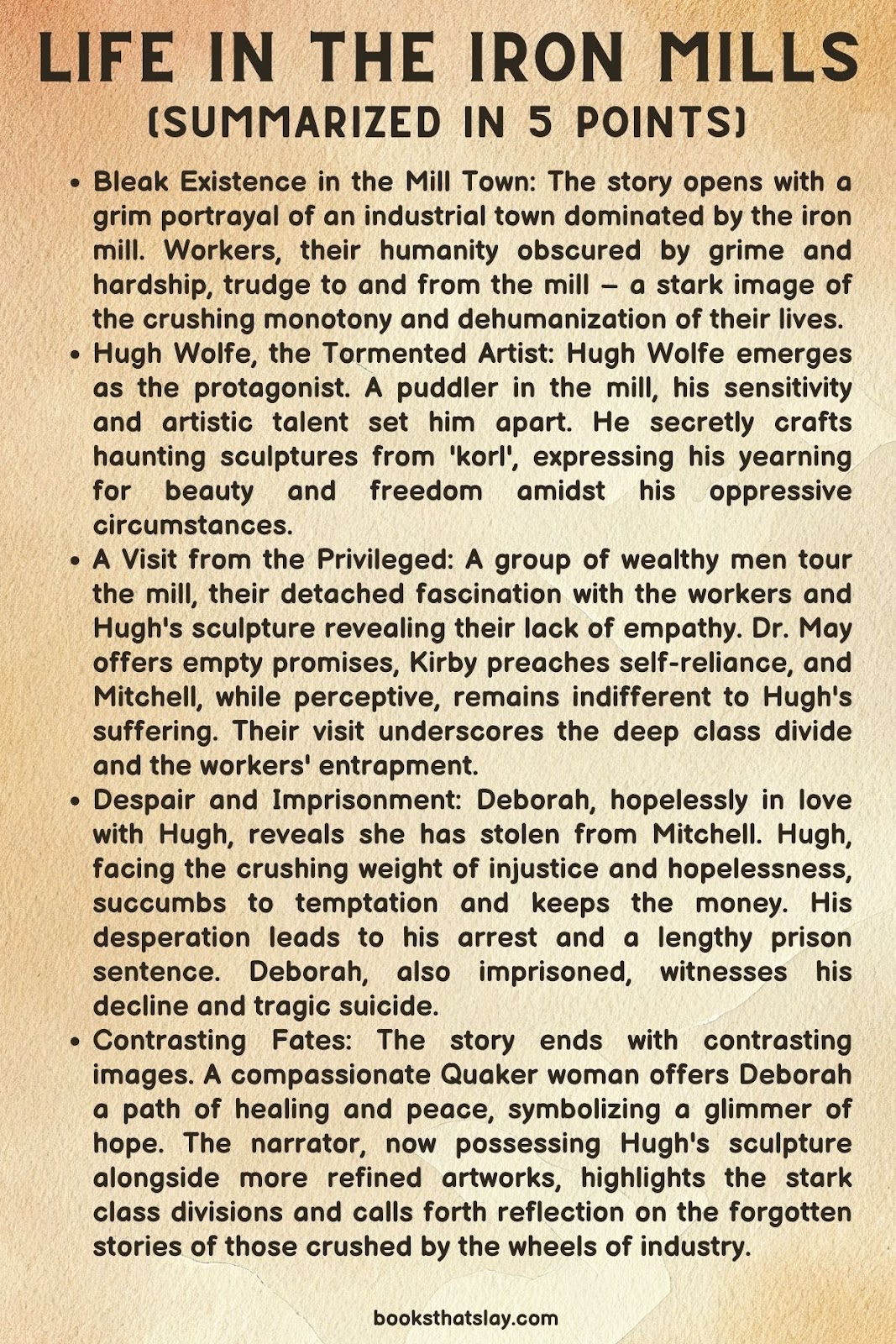

Summary

The novella opens with a bleak description of a grimy, industrialized Virginia town choked by smoke and ash.

An unnamed narrator, later presumed female, gazes from her window at the miserable procession of mill workers. Her focus shifts to Hugh Wolfe, a man burdened by a life of relentless toil, and she decides to tell his story.

We meet Deborah, a hunchbacked millworker with an unrequited love for Hugh.

Exhausted from her workday, she resists her coworkers’ temptations and returns home dedicated to caring for the other boarders. One of these boarders is Janey, a young girl whose father has been imprisoned. We learn that Hugh is not yet home, and Deborah sets out to bring him his meal.

Hugh Wolfe is portrayed as a puddler, a physically demanding and dangerous job within the iron mill. He is perceived as an outsider by his coworkers, his artistic nature setting him apart.

In secret, he uses ‘korl’, a malleable waste product, and transforms it into beautiful yet haunting sculptures.

A group of wealthy, detached men tour the mill: Clark Kirby, the owner’s son; Dr. May, the town doctor; Mitchell, Kirby’s foppish brother-in-law; and a curious reporter.

They are struck by Hugh’s sculpture depicting a desperate woman, their appreciation tainted by a shallow understanding of the workers’ plight.

The men’s indifference to Hugh’s suffering is profound. Dr. May offers empty platitudes about self-improvement, while Mitchell, though recognizing Hugh’s potential, does nothing to help.

Their fleeting acknowledgment only serves to highlight Hugh’s entrapment in his desperate circumstances.

Walking home with Deborah, Hugh grapples with despair, and his initial impulse to return the money he finds tucked in his coat falters.

Driven by the injustice of a life of endless labor with no hope of escape, he loses his way. He roams the streets and even seeks solace in a church, but the preacher’s words fail to resonate with his broken spirit.

A newspaper clipping informs the reader of Hugh’s arrest for theft and his lengthy prison sentence.

Deborah, sentenced for a shorter term, desperately pleads with Hugh when she glimpses him sharpening a piece of metal against the bars of his cell. Though she is forced away, her fears are confirmed when Hugh commits suicide.

A compassionate Quaker woman cares for Deborah after her release from prison, offering a path to peace.

The narrator ends the tale by revealing she owns Hugh’s haunting sculpture, juxtaposing it with other, more refined pieces of art.

Despite tragedy, the remnants of Hugh’s genius and Deborah’s transformation suggest a tentative glimmer of hope within this otherwise stark portrayal of industrial despair.

Characters

Hugh Wolfe

Hugh is the complex and tortured heart of the novella. A mill worker trapped in grinding poverty, he possesses a sensitive soul and an artistic talent that sets him apart from his fellow laborers.

His sculptures crafted from ‘korl’ represent his desperate yearning for beauty and escape from his bleak existence. The conflict between his aspirations and his harsh reality drives him to despair.

Hugh embodies the destructive cost of industrialization on the human spirit, highlighting how a society obsessed with production grinds down those with potential for something greater.

Deborah

Deborah’s physical deformity masks a fiercely devoted and courageous spirit. Her unrequited love for Hugh reveals her capacity for self-sacrifice, yet this same love drives her to a morally perilous act.

Deborah’s actions underscore the limited options and desperate measures available to the downtrodden within such a rigid class system.

Despite her flaws, she embodies resilience and humanity within a world designed to destroy both.

The Narrator

The unnamed narrator serves as a bridge between the world of the mill workers and the likely readership of the time – the more privileged classes.

Their perspective is tinged with both pity and a sense of distance, highlighting the vast gulf between social classes.

The narrator’s good intentions stumble against a lack of true understanding; they frame the story, demonstrating the challenges of empathy and action even when a desire to help is present.

Doctor May

Dr. May is a symbol of the hypocrisy and empty paternalism of the upper class. He dispenses platitudes and self-help advice to Hugh, masking his indifference and unwillingness to offer real assistance.

His character reveals how those in power often absolve themselves of responsibility by placing the burden of change solely on the oppressed.

Mitchell

A more nuanced figure than his companions, Mitchell possesses a perceptive eye. He recognizes Hugh’s talent and the injustice of his situation, yet his inaction makes him complicit.

Mitchell illustrates the paralysis that can occur even among those with awareness; a passive acknowledgement of suffering ultimately does nothing to change it.

Other Characters

Clarke Kirby stands for unchecked capitalism, oblivious to the human toll exacted by his wealth. Janey’s vulnerability represents the potential for innocence to be crushed by industrialization’s relentless force.

Finally, the Quaker Woman symbolizes a path beyond despair, offering Deborah a chance for peace and demonstrating that compassion, however late, can provide a flicker of hope.

Themes

The Crushing Weight of Social Inequality

Davis paints a stark picture of the vast gulf separating the laboring class from the privileged elite. The mill workers live in squalor, their bodies and spirits broken by the relentless toil demanded of them.

In contrast, the upper-class visitors to the mill view the workers with a mix of curiosity and disdain, utterly detached from their suffering. This juxtaposition underscores the deep injustice of a society where some are denied basic dignity, trapped in a cycle of poverty and despair while others enjoy wealth and leisure without question.

Davis forces the reader to confront the consequences of rampant inequality, sparking a conversation about social responsibility that remains relevant today.

The Destructive Power of Hopelessness

The characters in the story are trapped in an environment that offers no escape, no opportunity for betterment.

Hugh Wolfe, a man with artistic talent, is ground down by his monotonous and physically demanding work. Even when opportunities fleetingly present themselves, like the acknowledgement by the upper-class visitors, the entrenched social structures ensure that nothing can truly change.

This pervasive hopelessness leads to desperation and, ultimately, self-destruction in Hugh’s case.

Deborah’s willingness to compromise her morals through theft is another consequence of this despair.

Davis highlights how a lack of hope can corrupt and destroy the human spirit.

The Search for Beauty and Meaning amidst Squalor

Despite the bleak and oppressive setting, Davis infuses a poignant search for beauty and meaning into the story.

Hugh’s act of transforming waste material into moving art symbolizes the enduring power of the human spirit to find expression, even in the most dire circumstances. Deborah’s unwavering love for Hugh, however unreciprocated, represents both the beauty and pain of human connection.

And the Quaker woman’s quiet acts of compassion at the end offer a flicker of hope that kindness and a better way of life are still possible.

This theme invites reflection on the resilience of humanity and the importance of seeking out meaning and beauty, even within a harsh and unyielding world.