Little Women Summary, Characters and Themes

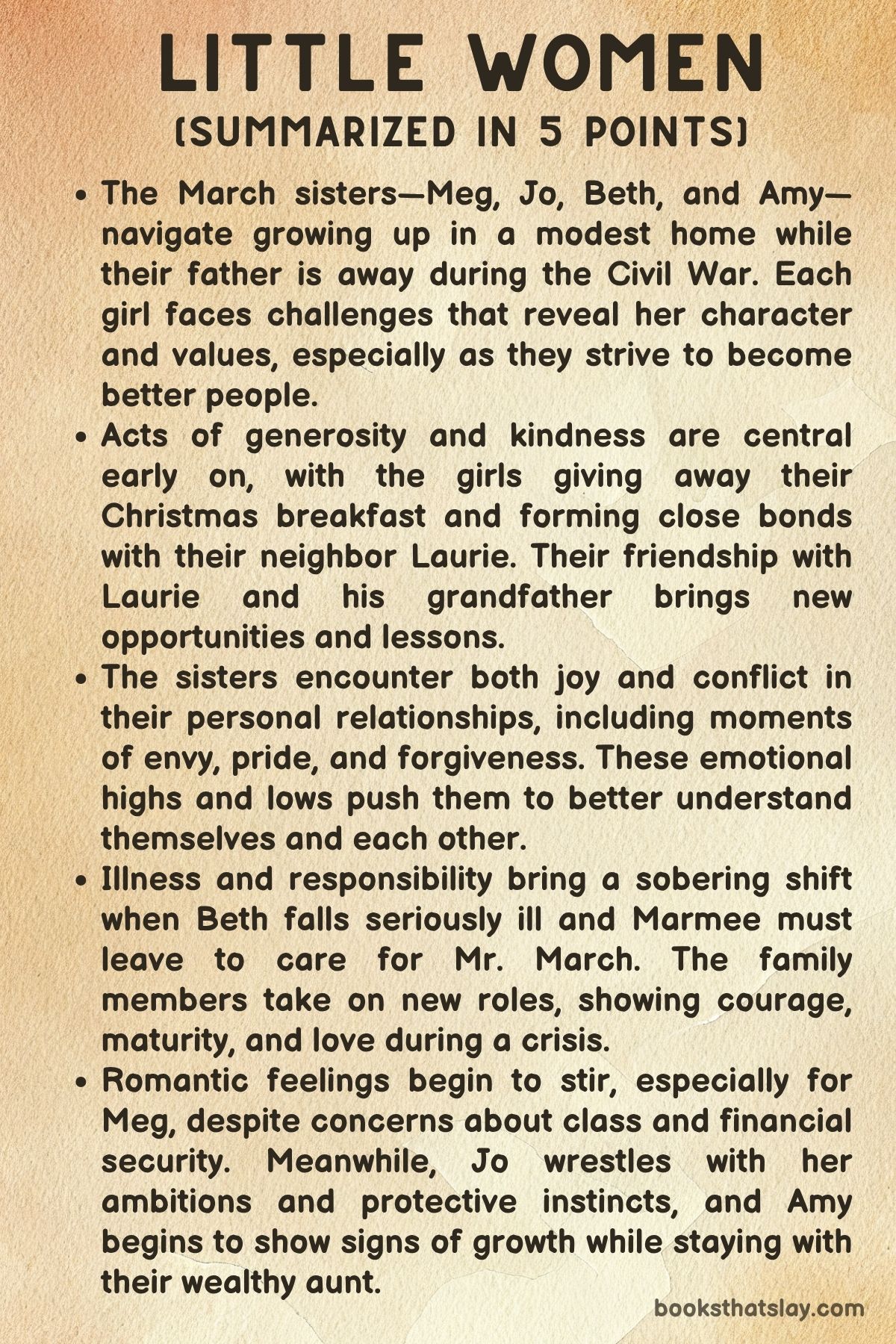

Little Women by Louisa May Alcott is a famous coming-of-age novel set during the American Civil War, focusing on the lives of four sisters—Meg, Jo, Beth, and Amy March—living in New England. First published in 1868, the story reflects themes of family, morality, sacrifice, and personal growth.

Each sister has her own personality and dreams, and together they navigate the challenges of adolescence, poverty, illness, and changing social expectations. With their father away at war, their mother Marmee guides them through hardship with compassion and wisdom. Alcott’s writing balances sentiment and realism, capturing the enduring power of sisterhood and self-discovery.

Summary

The story begins during a cold Christmas in the March household. The four sisters—Meg, Jo, Beth, and Amy—feel the absence of their father, who is away serving in the Civil War.

Despite their modest circumstances, they are encouraged by their mother, Marmee, to be grateful and kind. On Christmas morning, they give their breakfast to a poor family, and later receive thoughtful gifts and enjoy a play they perform together.

Their shared values and dreams are clear from the start. Each girl stands out with a unique personality.

Meg, the eldest, is gentle and proper. Jo is headstrong and dreams of being a writer.

Beth is shy and musically gifted. Amy is artistic and concerned with social status.

They support one another through small everyday struggles and moral lessons. When Jo meets Laurie, the rich boy next door, a close friendship forms.

The March family bonds with Laurie’s grandfather, Mr. Laurence, who invites Beth to play his piano. This marks the start of a tender connection between them.

Meg experiences the tension between modest living and the appeal of wealth when she stays with a wealthy friend. She temporarily indulges in a lifestyle she doesn’t quite belong to.

Jo’s friendship with Laurie grows, while Amy feels left out when she’s not invited to the theatre. In anger, Amy burns Jo’s cherished manuscript, causing a serious rift.

The incident is mended after Jo saves Amy from drowning during a skating accident. Jo is forced to confront the importance of forgiveness.

Beth’s quiet goodness earns her a personal gift from Mr. Laurence—a small piano. Meanwhile, the girls experiment with taking a week off from household duties.

They soon realize the value of effort and routine. They start a secret literary club and each shares her dream for the future.

Jo wants to be a famous author. Meg dreams of marrying well.

Beth hopes to stay at home. Amy wishes for refinement and art.

As the girls mature, Jo secretly submits a story for publication. Mr. Brooke, Laurie’s tutor, shows interest in Meg, taking one of her gloves as a token.

Their budding relationship is hinted at, though not yet confirmed. News soon arrives that Mr. March is gravely ill, and Marmee prepares to travel to Washington.

Jo cuts and sells her hair to help fund the trip. Her act deeply moves the family.

During Marmee’s absence, Beth becomes critically ill with scarlet fever after helping the Hummels, a poor family. Amy is sent to live with Aunt March to avoid exposure.

The household is filled with anxiety. Beth’s condition worsens, but she gradually begins to recover after Marmee returns home.

Amy matures during her stay with Aunt March. She takes her lessons seriously and even writes a “will” in case something happens to her sister.

Meanwhile, Laurie mischievously teases Meg about Mr. Brooke, causing Jo to react angrily. The misunderstanding is resolved, and Mr. Brooke’s quiet interest in Meg continues to develop.

Aunt March objects to the idea of Meg marrying someone with limited financial means. Meg stands firm in her feelings, showing her growing independence.

By the end of this portion of the story, each of the girls has experienced personal trials and small victories. Beth’s slow recovery brings the family hope.

Amy returns home with a new level of maturity. Jo, still driven by ambition, struggles with her temper but shows signs of reflection.

Meg begins to understand her own heart. The curtain closes on this stage of their lives with the sisters closer than ever, having gained strength through love, hardship, and resilience.

Characters

Jo March

Jo is the spirited, headstrong second daughter of the March family and easily one of the most vividly drawn characters in the first part of the novel. She is independent, fiercely intelligent, and deeply passionate about her writing, which she views both as an outlet for expression and a path to financial independence.

Jo resists traditional gender roles and expectations — she prefers “boyish” behavior, shuns fashion, and dreams of adventure and authorship rather than marriage. However, her character arc in these early chapters also shows internal conflicts, especially regarding her temper and impulsiveness.

Her grief and eventual forgiveness after Amy burns her manuscript highlight her emotional growth. So does her sacrifice in cutting her hair to help fund her mother’s trip to see their ailing father.

Jo’s deep, protective love for Beth and the intensity of her bond with Laurie shape many of her decisions. These elements add complexity to her character, making her journey as a flawed but deeply caring sister all the more compelling.

Meg March

Meg, the eldest of the sisters, embodies domestic virtue and conventional femininity. Yet she also wrestles with vanity and class aspirations.

Her experiences navigating upper-class social scenes — particularly during her visit to the Moffats’ — expose her vulnerability to appearances and material comfort. Over time, she ultimately comes to question these desires.

Despite her prim and proper demeanor, Meg demonstrates a quiet strength and a growing sense of personal agency. This becomes clear when she defends her interest in Mr. Brooke against Aunt March’s disapproval.

She asserts her right to choose love over wealth. Meg’s story in the first 23 chapters is one of balancing romantic idealism with maturity.

Her gradual acceptance of Brooke’s humble position signals a turning point in her self-understanding and values.

Beth March

Beth is the most self-effacing and morally pure of the March sisters. She is often described in near-angelic terms.

She is quiet, gentle, and happiest within the confines of home, where she plays the piano and cares for others with serene devotion. Her character serves as the emotional heart of the family.

Beth’s fear of strangers is overcome through her bond with Mr. Laurence, whose gift of a piano symbolizes both her musical talent and her silent influence on others. Her near-death experience brings the family into a profound emotional focus.

Beth’s illness with scarlet fever is a pivotal event. It draws out deep care, fear, and transformation among all the sisters, especially Jo.

Beth may not have the dramatic arcs of her sisters, but her quiet heroism and saint-like patience provide the moral grounding for the novel’s early chapters.

Amy March

Amy, the youngest March sister, begins the novel as vain, self-centered, and fixated on outward appearances. She is particularly concerned with social status and material elegance.

Her early immaturity is showcased when she burns Jo’s manuscript in a fit of childish revenge. This moment leads to one of the novel’s most emotionally charged conflicts.

However, her character starts to shift during her stay with Aunt March. There, she confronts serious matters like Beth’s illness and even creates a “will” to express her thoughts and belongings.

These moments mark the beginnings of her transformation from a superficial child into a more thoughtful and graceful young woman. Amy’s artistic aspirations and desire to become a “refined lady” point to her awareness of beauty and culture.

Her growth in these early chapters lies in learning restraint, empathy, and the value of family over personal pride.

Marmee (Mrs. March)

Marmee is the moral and emotional backbone of the March family. With her husband away at war, she manages the household with grace, warmth, and moral wisdom.

She guides her daughters not through harsh discipline but by embodying the values she hopes to instill — selflessness, humility, and inner strength. Marmee is not idealized without depth.

She confesses to Jo her own struggle with anger in her youth. This offers Jo a model of self-mastery.

Her departure to care for Mr. March and her timely return during Beth’s illness reveal her as both a nurturer and a pillar of resilience. Marmee’s steady presence ensures that the household does not merely survive hardship but uses it as a vehicle for moral growth and familial closeness.

Laurie Laurence

Laurie is the charming, wealthy boy next door who quickly becomes an honorary member of the March family. His friendship with Jo is at the center of his early character development.

Their relationship is filled with mischief, warmth, and growing emotional complexity. Laurie is drawn to the March family for the comfort and affection it offers, which is lacking in his own austere home.

He is playful, intelligent, and occasionally impulsive, as seen when he pranks Meg regarding her relationship with Mr. Brooke. Yet, he also shows loyalty and generosity.

Notably, he sends Mr. Brooke with Marmee to visit the ailing Mr. March. Laurie’s evolving feelings, especially toward Jo, begin to take shape.

These early chapters lay the groundwork for future emotional entanglements. His character represents the interplay between youthful exuberance and the yearning for deeper connection and purpose.

Mr. Brooke

Mr. Brooke, Laurie’s tutor, is introduced as a quiet, dependable, and honorable young man. His growing affection for Meg is developed subtly through gestures like holding onto her glove.

Despite his modest means, he emerges as a sincere and respectful suitor. His values align with those of the March family — hard work, honesty, and humility.

His willingness to accompany Marmee to Washington without hesitation further demonstrates his devotion. Although he remains a peripheral character in these early chapters, his presence is important.

He serves as a catalyst for Meg’s personal evolution. Mr. Brooke’s character supports the broader theme of love founded on character rather than wealth.

Aunt March

Aunt March, the wealthy and sharp-tongued aunt, provides a foil to Marmee’s gentle guidance. She represents traditional ideas about marriage, money, and social status.

She often pressures the girls to conform to societal expectations. Her influence on Amy, while demanding, also becomes an unexpected avenue for Amy’s growth in maturity and refinement.

Though often critical and overbearing, Aunt March is not without affection. Her attempts to “settle” the question of Meg’s future illustrate her belief in protecting family interests.

She operates from a rather self-important vantage point. Her character embodies the tensions between old-world practicality and the March girls’ romantic idealism.

Themes

Family and Sisterhood

One of the most prominent themes in Little Women is the enduring bond of family and sisterhood. From the very first chapter, the closeness of the March sisters — Meg, Jo, Beth, and Amy — is at the heart of the narrative.

Their interactions reveal a family unit that, though often tested by hardship, remains grounded in love, support, and shared moral values. Whether it is sacrificing their Christmas breakfast for a needy family or supporting each other’s ambitions, the girls demonstrate deep affection and loyalty.

Conflicts arise — such as Jo’s anger when Amy burns her manuscript — but these are resolved with genuine forgiveness, reinforcing the idea that familial bonds can withstand emotional pain and jealousy. The absence of their father during the war only heightens their reliance on one another and their mother, Marmee, whose nurturing presence guides them through hardship.

The girls’ commitment to growing as individuals is deeply rooted in their shared identity as a family. The domestic scenes — sewing, reading, play-acting — are not just glimpses of daily life but acts that reinforce their unity.

Even as romantic interests and outside relationships begin to influence their lives, the sisters constantly return to one another for emotional grounding. In these early chapters, Alcott presents family not as an idealized structure but as a dynamic relationship in which conflict, change, and affection coexist.

The theme insists on the value of connection. It shows the importance of being seen and understood by those closest to you, even in times of turmoil.

Personal Growth and Moral Development

The journey of each March sister is marked by a conscious pursuit of personal growth and moral development. This theme is heavily inspired by The Pilgrim’s Progress, which the girls adopt as a model for self-improvement.

Each sister faces challenges that test their individual weaknesses and encourage virtues like patience, humility, forgiveness, and fortitude. Meg, who is often tempted by luxury and status, must learn to reconcile her desires with her principles, especially as she begins to understand the complexities of romantic and social expectations.

Jo struggles deeply with her temper and pride. Her impulsiveness and sense of injustice often lead to clashes, particularly with Amy, but these incidents also become moments of reflection and change.

Beth, naturally gentle and timid, represents quiet strength. Her illness later becomes a pivotal moment for all the sisters, urging them toward greater compassion and maturity.

Amy, the youngest, evolves from a vain and self-centered child to a more thoughtful and emotionally intelligent young woman, especially during her time with Aunt March. These transformations are not portrayed as grand or sudden but as gradual, sometimes painful processes.

The book insists that virtue is something to be practiced daily, not merely aspired to. Alcott’s message here is that real growth involves struggle, sacrifice, and a willingness to confront one’s flaws.

The girls are not saintly; they are human, which makes their attempts at moral development more authentic and relatable. This ongoing theme of becoming better — not perfect — individuals is the ethical spine of the story.

Gender Roles and Expectations

Throughout the first twenty-three chapters, Little Women offers a quiet but firm critique of 19th-century gender roles and societal expectations. The March sisters inhabit a world where a woman’s future is largely defined by marriage, beauty, and domesticity.

Each sister wrestles with these expectations in her own way. Jo, in particular, represents a challenge to conventional femininity.

She is outspoken, ambitious, and dreams of a life beyond marriage. Her passion for writing and her resistance to the idea of becoming someone’s wife highlight her desire for independence and self-definition.

Meg, while more inclined toward traditional roles, finds herself caught between the romantic fantasy of wealth and the grounded reality of love and responsibility. Amy’s yearning for refinement and social status reflects a desire to succeed within the constraints imposed upon her, while Beth’s simplicity aligns more closely with the era’s ideal of feminine virtue.

Beth’s influence within the family is deeply felt despite her quiet demeanor. Alcott portrays these different reactions to gender expectations without judgment, instead presenting a spectrum of female identity.

Marmee also subtly challenges norms by encouraging her daughters to think for themselves and prioritize integrity over appearances or ambition. The theme of gender is not aggressively confrontational, but it is consistently present.

It invites the reader to question the limitations placed on women and to consider the value of choice, ambition, and authenticity.

Class and Social Mobility

Social class and the desire for upward mobility play a significant role in shaping the characters’ desires and dilemmas. The March family occupies a space of genteel poverty — they are educated, respected, and morally upright, but they lack wealth.

This creates a tension for characters like Meg, who is often exposed to wealthier peers and momentarily seduced by the lifestyle of opulence. Her visit to the Moffats, for instance, underscores the seductive power of wealth and the embarrassment that can come from economic disparity.

Amy also displays an acute awareness of class and dreams of marrying into wealth, seeing it as a path to respect and artistic fulfillment. The girls’ relationship with Laurie and his wealthy grandfather further illuminates the divide between social classes, even as their friendship bridges it.

Laurie’s acceptance into their world is based not on money but on shared values and genuine connection. However, the threat of class-based prejudice remains, as seen in Aunt March’s opposition to Meg’s potential marriage to Brooke, a man without fortune.

This theme challenges the notion that wealth should dictate personal worth or the viability of relationships. Instead, Alcott presents a nuanced picture: while money offers comfort and opportunities, true character and happiness cannot be bought.

The Marches’ modest life is filled with rich emotional and moral experiences. This suggests that dignity and virtue can thrive even in the absence of material wealth.

This treatment of class issues encourages a reevaluation of what it means to live a “successful” life.

Illness, Mortality, and Compassion

The theme of illness introduces a somber yet transformative element into the story, particularly through Beth’s contraction of scarlet fever. Her sickness not only acts as a test of the family’s emotional endurance but also becomes a catalyst for growth, reflection, and an outpouring of compassion.

Prior to this, the narrative is filled with smaller moral lessons. Beth’s near-death experience confronts the characters with the reality of mortality and the fragility of life.

Jo, who is fiercely protective of Beth, learns a deeper sense of responsibility and empathy. Amy, kept at a distance for her safety, undergoes a personal awakening about the seriousness of life, as seen in her creation of a “will” and her reflective behavior while staying with Aunt March.

Marmee’s return during Beth’s decline adds emotional weight to the story and highlights the nurturing power of maternal love. The household’s entire rhythm changes in the face of illness; daily routines give way to bedside vigils, and the family is united in fear and hope.

This period of crisis forces each character to confront what matters most. It strips away vanity and trivial concerns.

The way they care for Beth — with patience, tenderness, and hope — reflects a deep well of compassion that defines their relationships. The theme ultimately emphasizes that suffering, while painful, can deepen human connection and foster a greater appreciation for life.

Alcott uses this episode to explore how facing loss brings clarity to the characters’ values and affirms their capacity for love.