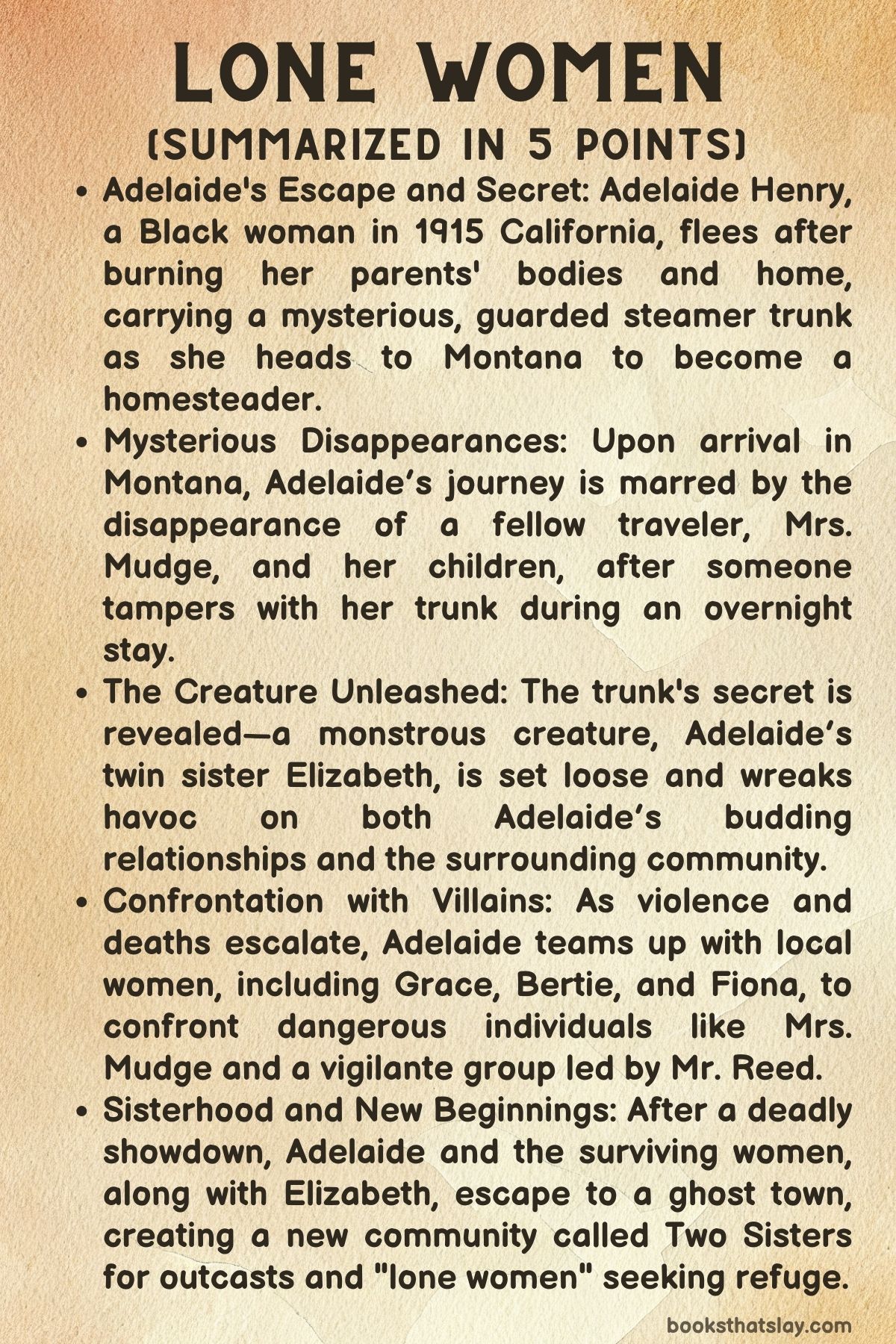

Lone Women Summary, Characters and Themes

Lone Women by Victor LaValle is a gripping historical novel set in 1915 that blends horror, historical fiction, and themes of isolation and survival. The story follows Adelaide Henry, a Black woman fleeing her troubled past to start a new life as a homesteader in the vast prairies of Montana.

She carries a mysterious steamer trunk, fiercely guarded, that holds more than just her belongings—it harbors a dark secret. As Adelaide navigates her new life, she encounters other “lone women,” forms unlikely alliances, and battles both external dangers and the haunting legacy she brought with her.

Summary

Adelaide Henry, a 31-year-old Black woman, finds herself in a perilous situation when her parents are violently murdered in their California home in 1915. To hide the disturbing truth, Adelaide burns their bodies along with the house and flees, carrying a mysterious steamer trunk.

This heavy trunk is her constant companion as she travels by boat to Seattle and then by train to Montana, where she plans to live as a homesteader on her own plot of land.

The contents of the trunk remain a secret, but Adelaide’s attachment and whispered conversations to it suggest something sinister lurks within.

Arriving in Big Sandy, Montana, Adelaide is greeted by Mrs. Reed, a prominent figure in town, who introduces her to Mr. Olsen, a wagon driver. Adelaide shares the wagon ride with a woman named Mrs. Mudge and her four apparently blind sons.

After the wagon gets stuck, the group takes refuge in an abandoned hotel. The next morning, Adelaide wakes up to find that her trunk has been tampered with and the Mudge family has vanished.

Reaching her rundown homestead, Adelaide begins to settle in and meets her neighbors, including Grace Price and her son Sam. Despite Grace’s critical nature, Adelaide forms a bond with her.

She also becomes acquainted with Matthew Kirby, a young man who seems interested in her. However, things take a terrifying turn when, after a night together, Matthew unlocks Adelaide’s trunk, unleashing the monstrous being inside.

The creature attacks Matthew, and Adelaide, although deeply shaken by his betrayal, cares for him until he recovers.

Later, Adelaide learns that Grace has been attacked by Mrs. Mudge, who is now pretending to be another person in town. Grace regrets not heeding Adelaide’s warnings about her, and together, they turn to another Black homesteader, Bertie Brown, for help.

As Adelaide returns home, she discovers the creature has escaped its confinement and now hides under her bed.

Mrs. Mudge soon appears at Adelaide’s cabin with the intent to rob and kill her, but the creature emerges, killing Mrs. Mudge and her two older sons, while the two youngest flee.

As time passes, more killings plague the area, and suspicion grows in Big Sandy. Adelaide confides in Grace, Sam, and Bertie that the creature is actually her twin sister, Elizabeth.

The women resolve to find Elizabeth and stop the chaos she is causing. Meanwhile, a vigilante group called the Stranglers, led by Mr. Reed, is hunting for Adelaide and her creature.

In a tense confrontation at the Big Sandy opera house, Elizabeth violently slaughters many of the townspeople who wronged Adelaide and her companions.

In the end, Adelaide, Elizabeth, and the other “lone women” retreat to an abandoned ghost town where they begin a new life together.

They eventually create a haven for outcasts, naming their community Two Sisters, in honor of Adelaide and Elizabeth. Their story becomes one of survival, sisterhood, and reclaiming power in a world that has cast them aside.

Characters

Adelaide Henry

Adelaide Henry is the protagonist of Lone Women, a complex, layered character burdened by both personal guilt and the weight of a violent past. As a 31-year-old Black woman in 1915 America, she embodies strength and resilience while grappling with the trauma of her parents’ deaths—a mystery that haunts her throughout the story.

Adelaide’s decision to burn her family home and flee to Montana speaks to her desire for a new start. It also hints at her internal turmoil and need to hide a darker secret.

Throughout her journey, she is portrayed as resourceful, courageous, and protective—especially regarding the steamer trunk, which contains her monstrous twin sister, Elizabeth. The tension between her desire for a solitary, anonymous life and the reality of needing help from others leads her into complicated relationships with people like Grace, Matthew, and eventually, Bertie and Fiona.

Adelaide’s ultimate revelation—that the creature is her sister—forces her to confront her guilt and responsibilities. She transforms from someone running from her past to someone embracing it. Her development illustrates a shift from isolation to community, from secrecy to trust.

Elizabeth Henry

Elizabeth, Adelaide’s twin sister, is physically monstrous, yet her existence is deeply tied to Adelaide’s sense of guilt and responsibility. Though Elizabeth spends most of the novel locked in the steamer trunk, her presence looms large, representing both Adelaide’s burden and her familial bond.

Elizabeth’s monstrosity is symbolic of how society marginalizes women, especially women of color, by making them appear monstrous when they do not conform. As a literal monster, Elizabeth acts out violently, but her actions are driven by survival instincts and familial loyalty.

She is neither purely evil nor a villain, but rather a tragic figure whose relationship with Adelaide mirrors the complex dynamics of love and guilt. When the sisters reunite near the end of the novel, Elizabeth absolves Adelaide of her guilt, and together, they find a sense of belonging with other marginalized women.

Elizabeth’s arc transforms from being Adelaide’s hidden shame to becoming a crucial figure of power and protection within the new community.

Grace Price

Grace is one of the most important people Adelaide meets on the prairie. She is a tough, self-sufficient woman who also functions as a mother to Sam.

Grace’s sharp exterior often hides her caring nature, though it becomes clear that her critical attitude stems from survival in a harsh, rural world. Grace’s relationship with Adelaide evolves from initial judgment to one of deep friendship and mutual dependence.

Grace plays an important role in helping Adelaide adapt to prairie life, providing both practical advice and emotional support. However, Grace also hides her own secrets—particularly her murder of Sam’s father—which speaks to her own moral complexities and the lengths she will go to protect her family.

Ultimately, Grace is a symbol of the difficult choices women have to make in a male-dominated, often violent world. Her ability to forgive Adelaide’s past mistakes shows her depth of character and her role as a protector of the women in her community.

Sam Price

Sam is Grace’s son and reveals himself to be a perceptive and brave young boy. Despite his youth, Sam has a clear understanding of the violence and complexities in his mother’s life, including her murder of his father.

His loyalty to Grace and growing trust in Adelaide create a bond between the three that transcends the typical adult-child dynamic. Sam also represents fluidity and resilience, especially when his birth as “Samantha” is revealed.

Mrs. Reed’s attempt to force Sam back into a traditional gender role by dressing him in a girl’s dress demonstrates the novel’s critique of rigid societal expectations. Sam’s trust in Adelaide and his insistence that Joab deserves a second chance show his remarkable sense of justice and empathy.

His character arc speaks to the theme of finding identity and acceptance in a world that tries to impose conformity.

Mrs. Jerrine Reed

Mrs. Reed is a powerful and controlling figure in the town of Big Sandy. She wields social and political influence, using it to maintain control over the community, particularly the women.

Her leadership of the “Busy Bees,” a group of vigilante women, reflects her obsession with maintaining moral and social order, and her willingness to use violence to achieve her goals. Mrs. Reed is also deeply racist and classist, making thinly veiled comments about Adelaide and Fiona, reflecting the larger societal prejudices of the time.

Her desire to “civilize” Sam by forcing him to conform to traditional gender norms shows her narrow worldview and manipulation of those around her. In the end, Mrs. Reed’s downfall comes at the hands of Elizabeth, the very creature she sought to destroy.

Her death symbolizes the collapse of the old, oppressive social order that she represented.

Matthew Kirby

Matthew is one of the few men in the novel who forms a connection with Adelaide, though their relationship ultimately sours. Initially, Matthew appears as a potential romantic partner, offering Adelaide companionship and understanding.

However, his curiosity and eventual betrayal—when he opens Adelaide’s trunk and unleashes Elizabeth—demonstrates his inability to fully respect Adelaide’s boundaries and secrets. His character arc reflects the novel’s critique of male entitlement and the dangers women face when their autonomy is violated.

Though Matthew survives the attack by Elizabeth, his relationship with Adelaide is irreparably damaged, symbolizing a breach of trust that cannot be repaired.

Bertie Brown

Bertie Brown is another Black woman living on the prairie, and her presence serves as a crucial counterpoint to Adelaide’s isolation. A businesswoman who runs the Blind Pig tavern, Bertie is resilient, pragmatic, and emotionally intelligent.

She is also in a romantic relationship with Fiona, which adds complexity to her character, particularly in the context of the time period. Bertie provides emotional support to Adelaide and helps her come to terms with her past.

Her role in the community is as much about creating a safe space for outcasts as it is about survival. Bertie’s relationship with Fiona, though kept private in a conservative society, offers a vision of love and partnership that defies the constraints of the time.

Bertie also plays a significant role in founding the new town, Two Sisters, embodying the novel’s theme of creating spaces for marginalized people.

Fiona Wong

Fiona is a Chinese-American woman who runs a laundry service in Big Sandy and is in a relationship with Bertie. She faces racial and economic discrimination, particularly from Mrs. Reed, who attempts to undermine her business.

Despite these challenges, Fiona is resourceful and loyal, especially in her friendship with Adelaide. Her connection to her family’s past and search for her father’s grave give her character a sense of personal history and emotional depth.

Fiona’s quiet strength and vulnerability make her an integral part of the group of women who band together to create a new community. Like Bertie, Fiona represents the theme of finding solidarity among women who are considered outsiders by society.

Joab Mudge

Joab is the youngest surviving son of Mrs. Mudge, and his character undergoes a significant transformation. Initially, he is part of his family’s criminal activities, but by the end of the novel, he seeks redemption.

His relationship with Sam and willingness to accept Sam’s offer of friendship highlight his capacity for change and his need for belonging. Joab’s journey from a villainous figure to someone deserving of a second chance reflects the novel’s themes of forgiveness and transformation.

His inclusion in the final group of survivors suggests that even those with a dark past can find redemption and community.

Mrs. Mudge

Mrs. Mudge is one of the novel’s antagonists, a conwoman who uses her children in her schemes and attempts to rob and kill Adelaide. Her brutality and ruthlessness contrast sharply with nurturing women like Grace and Adelaide.

Mrs. Mudge represents the dangers of isolation and desperation, as her survival tactics become increasingly violent and cruel. She meets her end at the hands of Elizabeth, underscoring the novel’s theme that violence begets violence, and those who prey on others will ultimately face their downfall.

Themes

Intersection of Race, Gender, and Isolation in Early 20th Century America

Victor LaValle’s Lone Women deftly explores the intersection of race, gender, and isolation, particularly as experienced by a Black woman in 1915. Adelaide Henry’s identity as a Black woman places her in a unique, precarious position.

She is part of two marginalized groups—Black people and women—each facing oppression in deeply ingrained ways within American society. The novel presents the additional complexity of Adelaide’s physical isolation as she flees to Montana, a place where the challenges of being a Black woman are magnified by the harsh and sparsely populated environment.

In this landscape, the historical context of racial discrimination compounds her experiences of being a “lone woman,” emphasizing the intersectionality of race and gender in a society that marginalizes both. The novel engages with this intersectionality in Adelaide’s struggles to fit into the small, white-dominated town of Big Sandy, as well as in her relationships with other women who suffer under the combined pressures of patriarchal and racial violence.

Bertie Brown, the other Black woman in Montana, serves as a parallel to Adelaide, as both women strive to navigate their isolation while negotiating the social codes imposed upon them. This theme demonstrates how systems of oppression intersect to create unique hardships for women of color, especially in isolated rural environments where there is little communal support.

The Burden of Secrets and Generational Trauma

The heavy steamer trunk that Adelaide carries with her serves as a powerful metaphor for the burden of family secrets and generational trauma. LaValle uses the trunk and the monstrous creature inside it as symbols of unresolved familial pain, passed down through the generations.

Adelaide’s creature, which is ultimately revealed to be her twin sister Elizabeth, represents the dangerous, destructive power of secrets that have been buried, locked away, and repressed. The violence surrounding Adelaide’s parents’ deaths is tied to these long-hidden family secrets, and her journey reflects the difficulty of reconciling with this past.

The creature’s constant threat also symbolizes the inescapable nature of trauma, which follows Adelaide no matter where she goes, lurking in the shadows and demanding confrontation. As Adelaide tries to leave her past behind, the creature repeatedly resurfaces, showing how trauma cannot be outrun, ignored, or hidden.

The novel ultimately argues that generational trauma, much like the creature, can only be dealt with through direct confrontation, understanding, and—crucially—acceptance, a process Adelaide undergoes in her final reconciliation with Elizabeth.

The Monstrous as Metaphor for Social Marginalization and the Outsider Identity

The figure of the monster in Lone Women serves as a multifaceted metaphor for social marginalization. It casts a spotlight on how those who do not conform to societal norms—whether due to race, gender, sexuality, or personal history—are perceived as monstrous.

Elizabeth, the physical manifestation of Adelaide’s hidden, monstrous secret, represents all that is feared, misunderstood, and ostracized in society. Adelaide herself occupies a marginal position as a Black woman, and her literal and metaphorical “creature” is an externalization of the monstrous otherness society projects onto those who do not fit into established norms.

By the end of the novel, Elizabeth is no longer merely a symbol of destruction and violence but an integral part of the “lone women” community. This signifies the acceptance of one’s full identity, even the parts deemed monstrous by a judgmental society.

LaValle cleverly uses the monstrous as a narrative device to explore how societal norms stigmatize and otherize those who are different. He also showcases the potential for marginalized people to reclaim that perceived monstrosity as a source of strength and community.

Female Solidarity in the Face of Patriarchal Violence and Oppression

One of the novel’s core themes is the necessity of female solidarity in overcoming the pervasive forces of patriarchal violence and oppression. Adelaide’s journey to Montana is an attempt to escape male-dominated spaces, but she soon realizes isolation does not protect her from patriarchy’s reach.

This is illustrated by the town of Big Sandy’s violent, male-dominated social order, personified in characters like Mr. Reed and The Stranglers. In contrast, the relationships between the lone women—Adelaide, Grace, Bertie, and Fiona—demonstrate the power of female solidarity in resisting and surviving male violence.

Each woman is marginalized in her own way, but by coming together, they create a space of mutual support and care. Their final act of resistance, culminating in the destruction of their male oppressors at the opera house, is a triumph of collective female strength over patriarchal violence.

This solidarity is not only physical but emotional, as the women share their deepest fears and traumas with one another, forging a bond that enables them to survive in a hostile world. The creation of the town of Two Sisters symbolizes the transformative power of female communities that operate outside patriarchal control, offering a vision of an alternative world where women’s independence and safety are prioritized.

Reclaiming the Narrative of the Frontier and Settler Colonialism

LaValle’s Lone Women subverts traditional narratives of the American frontier, which often glorify white male settlers as brave pioneers taming a wild, untamed land. Instead, LaValle’s frontier is a dangerous, isolating space, and the novel re-centers the narrative around those often excluded from conventional settler stories: women, especially women of color, and other marginalized individuals.

Adelaide’s story is not one of triumph over the land but of survival in the face of both external and internal threats. The frontier in Lone Women is not a place of opportunity and freedom but a landscape filled with violence, secrets, and isolation.

The novel critiques the myth of the self-reliant settler by showing that the women who ultimately find success in this harsh environment do so not through individualism but through community and solidarity. The inclusion of characters like Fiona Wong and the Mexican couple who assist Adelaide challenges the traditionally whitewashed narratives of the American West.

By framing the formation of Two Sisters, a community of women who are social misfits, as the true triumph of the story, LaValle reclaims the frontier as a place where marginalized voices can thrive and create a new, inclusive future.

The Ethics of Survival and Moral Ambiguity

Throughout Lone Women, LaValle explores the ethics of survival in a world where morality is often ambiguous. Adelaide’s actions—burning her parents’ bodies, keeping the secret of her sister’s monstrosity, and even engaging in violence—raise complex questions about what it means to survive in a hostile environment.

These moral ambiguities reflect the larger theme of how survival can demand difficult choices that blur the line between right and wrong. Adelaide’s decision to keep her sister locked away is both an act of love and a form of imprisonment, raising the question of whether she is protecting Elizabeth or perpetuating her suffering.

Similarly, characters like Joab and the Mudge family operate within their own moral codes, shaped by the brutal realities of life on the frontier. The novel presents survival as a messy, often morally compromising process, where characters must navigate personal and ethical dilemmas to protect themselves and their loved ones.

In this way, LaValle challenges the simplistic notions of good versus evil, offering instead a nuanced exploration of how individuals negotiate their morality in extreme circumstances.