Lunch Ladies Summary, Characters and Themes

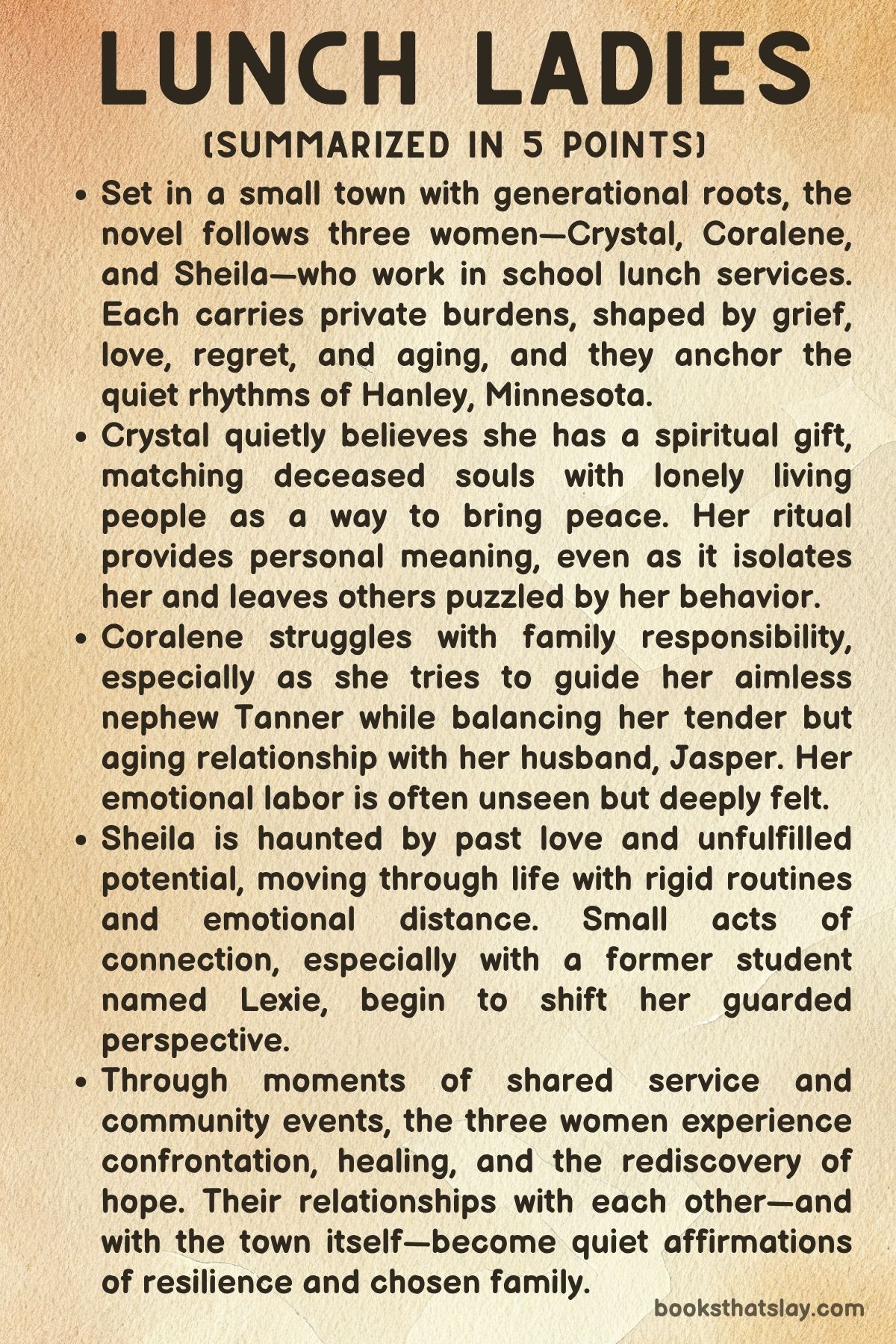

Lunch Ladies by Jodi Thompson Carr is a deeply moving and intricately structured novel set in the small town of Hanley, Minnesota, in 1976. At its heart, the book is a tender exploration of aging, grief, friendship, and generational responsibility, viewed through the lives of a group of women whose lives quietly intersect around family, memory, and community.

What begins with quirky rituals and day-to-day mundanity gradually unfolds into an intimate portrayal of women’s emotional endurance across decades. Rich with emotional honesty and Midwest charm, the story invites readers into kitchens, graveyards, parades, and quiet homes where loss, love, and resilience echo through generations.

Summary

In Lunch Ladies, Jodi Thompson Carr crafts a multigenerational portrait anchored by several women navigating personal loss, familial duty, and emotional reckoning in a tight-knit Midwestern community. The story begins in 1976 in Hanley, Minnesota, with Crystal, a middle-aged lunch lady whose peculiar hobby involves spiritually “pairing” the recently deceased with living soul companions based on obituary readings.

Crystal is somewhat isolated, maintaining a structured but emotionally guarded life. Her work in the school lunch department with Coralene and Sheila is both a literal and metaphorical place of nourishment, routine, and shared labor, though she harbors disdain for the administration’s rebranding of their role.

She finds comfort in predictable rituals, including Friday night cornbread dinners and interactions with her beloved cat, Terry.

Crystal’s coworkers offer contrasting emotional landscapes. Coralene is warm and deeply rooted in family life, sharing a strong marriage with her husband Jasper.

Her protective and loving care of her troubled nephew Tanner adds dimension to her character, revealing her ability to balance boundaries with compassion. Coralene’s stability and home life contrast sharply with Sheila’s solitary existence.

Sheila, emotionally armored and cynical, is haunted by a past romantic betrayal and the pressures of having once been a teacher with dreams abandoned after societal judgment. Her quiet friendship with a waitress named Lexie offers her a rare space for vulnerability, though loneliness continues to shadow her.

The generational thread extends through Crystal’s cousin Darcy and their grandmother Leonora. Darcy visits Leonora to help plan the town’s Bicentennial Parade float, joined by a group of eccentric elderly women from the hospital guild.

Darcy is perceptive and dutiful, sensing Leonora’s declining health and the emotional detachment from Crystal. Despite Darcy’s frustrations with her cousin’s aloofness, she continues to hope for deeper engagement.

Meanwhile, Crystal skips float duties to attend a funeral, pursuing her self-appointed mission of soul-pairing and confronting her grief over her mother and aunt, both of whom drowned years earlier. These losses remain the emotional cornerstone of Crystal’s fractured identity, compounded by her father Alfie’s abrupt abandonment after their deaths.

As the narrative shifts, deeper emotional undercurrents begin to surface. Crystal’s quiet observation of a grieving man at a funeral prompts her to reevaluate the legitimacy of her matchmaking mission—realizing some bonds of love exist with or without her intervention.

Her grief resurfaces in scenes at the cemetery, as she mourns her mother and aunt and reflects on memories that continue to define her. Leonora’s grief, meanwhile, stems from the layered losses of her daughters and her husband, Badger.

Her reflections while gardening reveal an inner world steeped in memory, metaphor, and sorrow, as she compares her daughters to differently thriving plants and expresses the ongoing work of tending to a family even through tragedy.

Sheila’s storyline progresses with increased emotional weight. Having cared for her mother until her death, Sheila now finds herself reflecting on her own empty routines.

When she reconnects with Tom, a former acquaintance and school plumber, there’s a spark of possibility. But her habitual emotional withdrawal stalls the potential for new connection.

The real rupture comes when she learns of the death of Ralph Blatson, the great love of her life. This discovery sends her into a psychological tailspin, unraveling years of suppressed emotions.

The pain culminates in an impulsive and final decision: Sheila takes her own life, leaving behind a note and a spotless kitchen. Lexie, the only person with whom Sheila maintained warmth, is left reeling—her grief amplified by the weight of a farewell that feels both deeply personal and devastatingly avoidable.

Parallel to Sheila’s collapse, Coralene continues to embody quiet endurance. Tanner, her nephew, encounters a traumatic event when he and his friend discover a crashed truck belonging to Tom.

The boys were gathering flowers for the parade—a gesture of tenderness ironically juxtaposed with the tragedy they stumble upon. Coralene and Jasper step in to guide Tanner through this event, reinforcing the book’s emphasis on adult compassion and emotional scaffolding for younger generations.

The town’s Bicentennial Parade serves as both a literal and symbolic climax. Leonora participates despite her failing health, her sharp wit still intact, though her reflections on mortality grow more pronounced.

Crystal, forced into coordinating the children handing out cookies, begins to let down her emotional walls. Her friend Ada’s public and unexpected declaration of loyalty marks a turning point, prompting Crystal to reconsider the meaning of friendship and openness.

When Crystal later joins Darcy and Leonora for a casual dinner, their shared moments are filled with undercurrents of reconciliation and shifting dynamics. Leonora, philosophical about her decline, speaks cryptically about her autonomy, even as Darcy and Crystal watch her with a mix of concern and reverence.

The final emotional beat comes with Crystal’s transformation. After the death of her cat Terry, she abandons her fixation with death and embraces the idea of new life by adopting more cats.

This act, while small, signals her readiness to nurture and connect again. Her grandmother, once emotionally distant, begins to respond with warmth, recognizing Crystal’s slow but genuine growth.

In the end, Lunch Ladies offers a moving mosaic of personal grief, small-town connection, and the generational roles women occupy as caretakers, keepers of memory, and emotional anchors. Through the lenses of Crystal, Sheila, Coralene, Leonora, and Darcy, the novel captures the often-unspoken labors of women—grieving in silence, extending love without guarantees, and building community even in the face of profound personal loss.

The story refuses sentimentality, instead finding meaning in quiet endurance, human connection, and the possibility of change at any stage of life.

Characters

Crystal

Crystal is the central and most enigmatic character in Lunch Ladies. She is a middle-aged woman who straddles the line between eccentricity and quiet despair, marked by peculiar habits such as spiritually “pairing” the deceased with living companions from obituaries.

This unusual practice is not mere whimsy; it is a coping mechanism born from unresolved grief and emotional dislocation following the deaths of her mother, Pearl, and aunt, Ruby. Crystal is socially withdrawn and deeply introspective, often isolating herself in rituals that allow her to feel a sense of control and meaning.

Her interactions with others, including her coworkers Coralene and Sheila, reveal a woman capable of loyalty and affection but emotionally guarded. Crystal’s emotional evolution becomes increasingly evident after her exposure to death, companionship, and the community around her.

Ada’s open declaration of friendship and Crystal’s eventual decision to adopt a new cat after the death of Terry signify a symbolic turning point—Crystal is beginning to reclaim life and embrace connection, however cautiously. Her relationship with Leonora, her grandmother, is strained by mutual misunderstanding and old wounds, but gradually softens, especially as Crystal begins to confront her emotional legacy and responsibility within her family.

Sheila Raymond

Sheila is a complex portrayal of stoicism masking immense sorrow. Once a passionate English teacher, Sheila retreated into the unglamorous role of a lunch lady after a painful romantic betrayal and the oppressive social judgments of the era.

Her life is a regimented exercise in solitude, broken only by her weekly dinners at Denny’s and her unexpectedly tender relationship with her waitress, Lexie. Sheila is fiercely private, emotionally repressed, and habitually resigned to disappointment.

However, her storyline—particularly her heartbreak upon discovering the obituary of her long-lost love, Ralph—unearths the profound grief that anchors her soul. The magnitude of her despair climaxes in her suicide, a deeply considered act that nonetheless leaves Lexie, and the reader, stunned and aching.

Sheila’s arc underscores the silent suffering that can thrive beneath functional exteriors and the devastating toll of unspoken pain. Her final gesture—a note and a pristine kitchen prepared for Lexie—speaks to the tragic duality of her character: the meticulousness of someone who lived with discipline, and the loneliness of someone who could not bear to be truly seen.

Coralene

Coralene serves as a pillar of warmth, steadiness, and generational compassion. A lunch lady by day and a devoted wife and guardian by night, she exemplifies domestic strength and emotional reliability.

Coralene’s marriage to Jasper is one of quiet, mutual respect—an anchoring contrast to the more fraught relationships around them. She takes her guardianship of Tanner, her nephew, with deep seriousness, seeing it as a sacred promise to her deceased sister.

Coralene’s strength lies not in grand gestures but in everyday acts of care: preparing lunch for Jasper, calming Tanner’s fears, and gently guiding him toward maturity. Her mother, Cora, further reinforces Coralene’s lineage of maternal wisdom, forming a triad of strong women who nurture through resilience and emotional intelligence.

Coralene’s capacity to balance empathy with accountability—especially in her conversations with Tanner about taking responsibility—positions her as a crucial emotional backbone in the novel’s network of women.

Leonora Daniels

Leonora, the family matriarch, is a character carved by loss, resilience, and an unflinching desire for autonomy. Once a vibrant, independent woman, she now wrestles with the indignities of aging and illness.

Her memories of her late husband Badger are saturated with longing, suggesting a love that still gives her spiritual sustenance. Leonora’s garden is both a literal and metaphorical space—where grief is tended like plants, and family is cultivated with care and effort.

Her reflections on raising her daughters, Pearl and Ruby, reveal a woman of nuance: she loved them differently but wholly. Leonora’s cryptic discussions about death and her choice to manage her own decline with quiet dignity speak to a generation that equates vulnerability with loss of control.

Her dynamic with Crystal and Darcy oscillates between affection, frustration, and fear of emotional irrelevance, yet in the end, she recognizes and welcomes Crystal’s reengagement with family life, suggesting reconciliation and mutual healing.

Darcy

Darcy operates as a bridge between generations—young enough to envision a future beyond Hanley but deeply tethered by familial obligation and love. As Leonora’s caretaker and Crystal’s cousin, she often assumes roles beyond her years, managing logistics and emotions with a maturity that is both admirable and burdensome.

Darcy’s struggle stems from being caught between wanting Crystal to engage more fully in their shared responsibilities and understanding the depth of Crystal’s unresolved grief. Her relationships—particularly the failed romantic endeavors—highlight her yearning for autonomy and adult identity.

Despite her frustrations, Darcy remains deeply empathetic, especially evident in her worry over Leonora’s health and her gentle persistence in pulling Crystal closer into the fold of family. She embodies the hope of continuity, resilience forged from inherited pain, and the desire to rewrite the emotional inheritance passed down through generations.

Ada

Ada emerges as a vibrant, unapologetically eccentric friend who embodies the sort of unconditional loyalty Crystal has never quite known. Her cheerful weirdness and unwavering affection become a turning point in Crystal’s emotional development.

By publicly affirming their friendship during the parade chaos, Ada cracks open Crystal’s hardened shell and reveals the possibility of connection unmarred by judgment or expectations. She symbolizes a form of love that is freely given, without strings or prerequisites—a love that Crystal, shaped by abandonment and death, has never quite trusted.

Ada’s presence infuses the story with warmth and a kind of radical acceptance, offering a vision of companionship that neither demands perfection nor flinches at emotional messiness.

Tanner

Tanner’s storyline provides a younger, more volatile perspective on grief and trauma. Raised by Coralene after his mother’s death and burdened by the absence of his father, Tanner oscillates between resentment and affection.

His encounter with Tom’s fatal accident introduces him to the rawness of mortality, prompting growth and emotional vulnerability. His act of collecting flowers with Craig for the parade table, a seemingly simple gesture, is layered with meaning: it’s an act of tribute, a cry for connection, and an assertion of love for the women who raised him.

Tanner embodies the pain of adolescence shaped by loss, but also the potential for renewal when guided by compassion and structure.

Themes

Female Friendship and Quiet Solidarity

Throughout Lunch Ladies, the story foregrounds an ecosystem of female friendship and solidarity built not on overt declarations but on consistent acts of care, presence, and recognition. Crystal, Coralene, and Sheila share a workplace in the Hanley School District’s lunch department, but their connection surpasses professional ties.

Even when their personalities and coping mechanisms vary wildly—Crystal’s mystical fixations, Coralene’s steady domesticity, Sheila’s guarded cynicism—their lives orbit a shared sense of duty and unspoken mutual understanding. Their friendship is not loud or sentimental but rooted in rituals: shared bus rides, familiar lunchroom banter, or casual check-ins.

These subtle but powerful patterns offer an emotional architecture that steadies each woman amidst life’s turbulence. The solidarity also stretches across generations.

Ada’s public affirmation of Crystal during the parade planning is a pivotal example of friendship offering validation where family has failed. Lexie’s vigilant concern for Sheila adds another dimension—one where a younger woman stands as a quiet but persistent witness to an elder’s suffering.

These friendships serve as lifelines, sometimes noticed only in absence, as shown in Lexie’s grief after Sheila’s suicide. They reveal how women often uphold one another not through grand interventions, but through consistent presence and emotional availability.

Grief, Death, and the Desire for Control

The characters in Lunch Ladies are repeatedly confronted by death—not just the literal end of life but the persistent emotional residue it leaves behind. Crystal’s compulsion to match the dead with suitable companions from the living world is an almost sacred ritual through which she attempts to impose order on the unpredictable nature of loss.

Her behavior, which at first reads as eccentric, gradually emerges as a coping mechanism formed in the wake of her mother and aunt’s tragic deaths. Crystal is not mourning in the conventional sense; she is trying to rewrite death as something purposeful and curated.

Similarly, Sheila’s response to the death of her former lover Ralph reveals how grief lingers even decades after a romantic wound. Her breakdown, especially after realizing that Tom’s absence at the parade was due to a fatal car crash, speaks to how easily a single moment can unearth buried sorrow.

Leonora’s arc also revolves around grief, but hers is shaped by time and acceptance. She contemplates her own mortality with intentionality, signaling her desire to orchestrate her end on her terms.

The persistent presence of death is not morbid for these women—it’s simply a reality to manage. They grieve not just people, but what might have been, what they never had the chance to repair, and the selves they had to abandon.

Generational Burden and Emotional Inheritance

Across multiple storylines, Lunch Ladies presents generational responsibility not as a chore, but as an unspoken, often painful, inheritance. Crystal was raised by Leonora after her parents’ deaths, but the emotional gaps in that arrangement still reverberate.

Leonora, shaped by her own hardships, cannot offer Crystal the language of love or comfort she needs, even though she tries in her own stern, practical way. Coralene’s devotion to her nephew Tanner, a child not biologically hers, echoes this dynamic.

Her steadfast guardianship stems from a promise made in the wake of her sister’s death—another example of a woman stepping into a maternal role because she must, not because she was prepared to. Darcy, meanwhile, becomes the quiet caretaker for Leonora in her old age, often trying to manage both her grandmother’s health and her cousin Crystal’s emotional reticence.

Each of these characters shoulders more than they were meant to carry, often without recognition. What connects them is their choice to continue carrying it, because to do otherwise would feel like failure.

Their emotional inheritances—grief, silence, unspoken expectation—are as tangible as any heirloom. These women are simultaneously products and stewards of their lineage, sculpting the next generation not through lessons, but through presence and example.

Loneliness and the Ache for Recognition

Loneliness is not incidental in Lunch Ladies; it is an active, shaping force that haunts nearly every character. Sheila is perhaps its most distilled representation.

Her life has been a gradual retreat from public engagement into a world of routine and guarded detachment. Yet under her controlled facade lies an overwhelming desire for someone to truly see her.

Lexie’s friendship cracks that shell, offering moments of comfort, but it’s not enough to prevent Sheila’s final decision. Her suicide is not only an escape from pain but a tragic assertion of control over a life that rarely felt acknowledged.

Crystal, too, operates from a deep well of isolation. Her hobbies—matching obituaries, eating alone with her cat—aren’t simply quirks but shields against the hurt of disconnection.

Her transformation begins not with therapy or epiphany, but with a friend’s simple declaration: “I love you anyway. ” Even Leonora, despite being surrounded by family, harbors a private loneliness rooted in age, memory, and the absence of her husband.

The loneliness in the novel is nuanced. It isn’t just about being physically alone but about not feeling seen, understood, or essential.

The story reveals how human connection, however fleeting or imperfect, can interrupt that ache—if only momentarily.

Care Work as Identity and Resistance

Whether making meals, organizing parades, or tending to the emotional needs of others, care work in Lunch Ladies emerges as both a daily task and an assertion of personal and communal value. Crystal, Coralene, and Sheila take pride in their roles as lunch ladies, rejecting the bureaucratic renaming of their department as “Nutrition Services.

” For them, feeding children is not just a job; it’s a dignified form of service. Coralene’s domestic rituals—preparing Jasper’s lunch, cleaning dishes, guiding Tanner—are not treated as chores, but as enactments of love and stability.

Even Leonora, physically weakened by illness, maintains her garden with symbolic tenacity, seeing it as a reflection of family. These acts, often dismissed by society as invisible labor, become central to the women’s identities.

But beyond identity, care becomes resistance: against erasure, against being sidelined in old age, against the devaluation of feminine labor. In a world that often strips aging women of agency, their insistence on nurturing, feeding, planning, and protecting reclaims power.

The care work in the story is also communal. The older lunch ladies take charge during the parade, demonstrating competence and purpose.

Through caregiving, the women forge bonds, preserve dignity, and subtly redefine what it means to lead, to serve, and to be remembered.