Mark Twain by Ron Chernow Summary, Characters and Themes

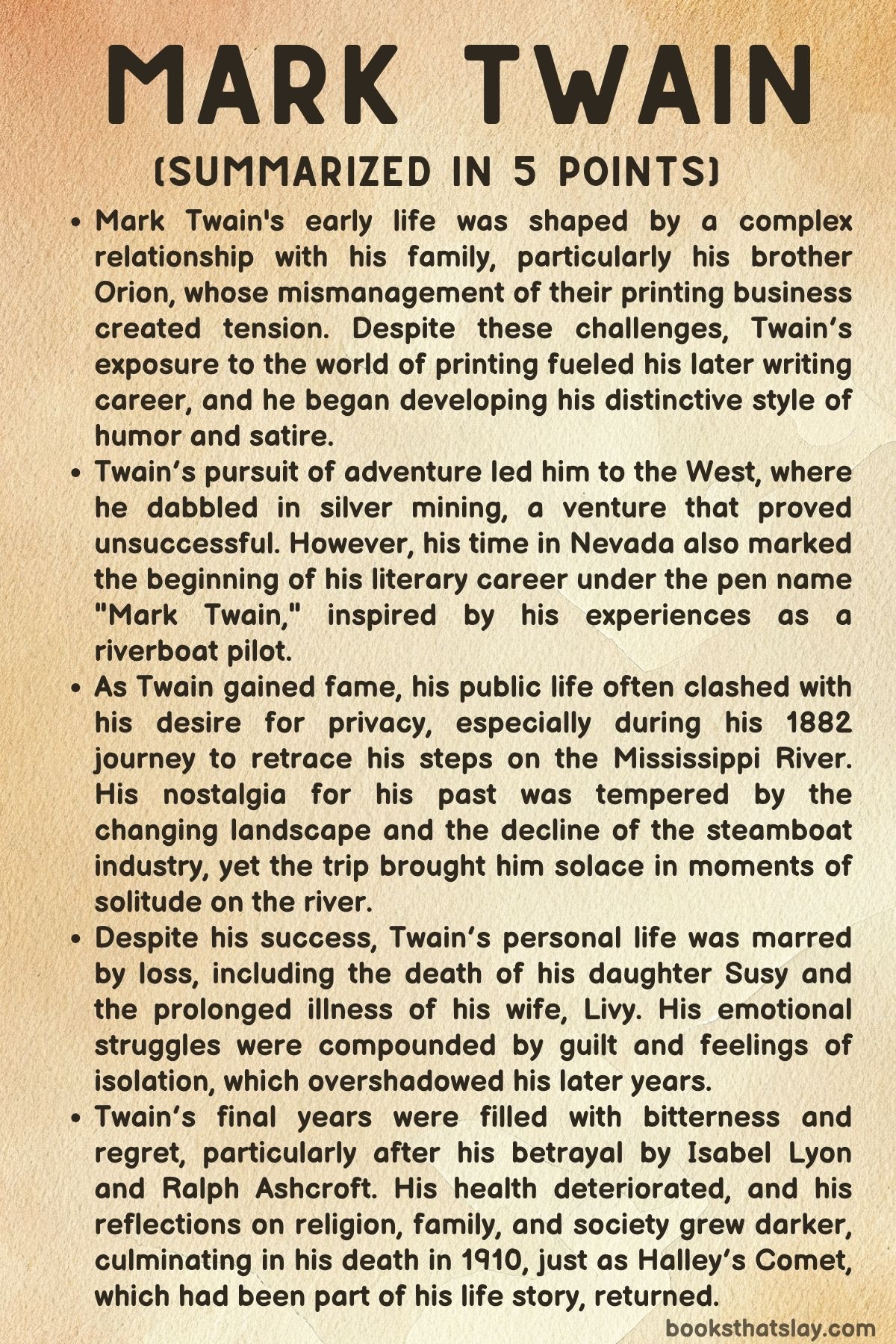

Mark Twain by Ron Chernow is an exploration of the life of one of America’s most iconic figures. Samuel Langhorne Clemens, known by his pen name Mark Twain, was more than just a celebrated author; he was a complex man whose life and works continue to resonate today.

This biography takes a deep dive into Twain’s personal experiences, including his childhood, career, family, and the social issues that shaped his writing. Through Chernow’s lens, we gain an intimate understanding of the contradictions that defined Twain, from his humor and wit to his reflections on life, death, and morality.

Summary

Samuel Langhorne Clemens, later known as Mark Twain, grew up in a family that faced constant financial struggles. His father’s death when Clemens was young marked a pivotal moment in his life, and the financial instability that followed left a significant impact on his character.

Clemens, nicknamed Sam, had a complex relationship with his brother Orion, who managed the family’s newspaper but struggled with poor business decisions. Despite their difficulties, Sam’s early exposure to the printing business was formative.

At the age of fifteen, he worked as a printer for Orion and developed a deep resentment toward his brother. His frustration was not just due to the strained family dynamics but also because of his brother’s failure to achieve success.

Over time, Sam became increasingly dissatisfied with his life in Hannibal, Missouri, and his desire for independence led him to leave and work as a printer in St. Louis.

His yearning for adventure and new experiences took him to New York City, and eventually, to the West.

In the West, Sam tried his luck in silver mining. Although he failed to find the wealth he had hoped for, it was during this time that he began to write, working as a journalist for the Territorial Enterprise in Virginia City, Nevada.

It was also here that Sam adopted the pen name Mark Twain, which was derived from a riverboat term indicating a safe depth of two fathoms. Sam’s time in Nevada marked a crucial turning point in his career, allowing him to combine his storytelling abilities with his sharp observations of the world around him.

His writing was filled with humor, satire, and social commentary, often poking fun at the absurdities of human nature.

As Twain’s writing gained popularity, he explored a wide variety of topics, from his travels to his reflections on society. He began to form a distinctive literary voice that incorporated humor, wit, and criticism of the Gilded Age.

His works like The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn and The Adventures of Tom Sawyer became iconic in American literature. Twain’s success as a writer was complemented by his growing fame as a public speaker.

His lectures, which were a blend of humor and social critique, further cemented his place in American culture.

Twain’s personal life was marked by both joy and sorrow. He married Olivia “Livy” Langdon, with whom he had three daughters.

His relationship with Livy was deeply affectionate, but their family life was far from perfect. Twain’s heartache began when their first daughter, Susy, died at a young age, which left a permanent scar on the family.

Twain’s grief over Susy’s death was compounded by his growing concerns about his own health and well-being. Despite the challenges, Twain remained deeply devoted to his wife and daughters.

However, his relationship with his father was more complicated, as his father had died when Twain was only eleven, leaving a void in his life.

As Twain aged, his views on race evolved. He grew up in a slave-owning family in the South, which influenced his early views on race.

However, as he matured, Twain became a staunch critic of slavery and racial prejudice. His friendship with figures like Frederick Douglass helped shape his evolving perspective on racial issues.

Despite his personal growth, Twain’s legacy is complicated by the use of racist language in some of his works, particularly in Huckleberry Finn. Nonetheless, his lifelong engagement with issues of race demonstrates his complex relationship with the societal norms of his time.

Twain’s later years were marked by increasing personal tragedy. After Livy’s death in 1904, Twain’s emotional and physical health began to deteriorate.

His grief was compounded by the ongoing struggles with his daughter Clara, who faced emotional difficulties following Livy’s death, and Jean, who battled epilepsy. The family’s financial troubles also weighed heavily on Twain, adding to his sense of isolation.

He continued to write, but his later works, including Letters from the Earth, reflected his disillusionment with life, religion, and human nature.

One of the most painful experiences of Twain’s final years was the betrayal by Isabel Lyon, his secretary, and Ralph Ashcroft, who had been close to the family. Twain had trusted Isabel, but he discovered that she had been embezzling funds and engaging in deceitful behavior, which further strained his relationship with his daughters.

Twain’s anger toward Isabel and Ashcroft fueled his writings during this time, as he vented his frustrations in letters and manuscripts.

Twain’s health continued to decline, and he suffered from various ailments, including angina pectoris. He spent much of his time at his home, Stormfield, where he reflected on his life and writings.

Despite his physical decline, Twain remained intellectually active, indulging in his interest in literature, astronomy, and religious satire. His later years were also marked by his sense of loss and regret, particularly regarding his treatment of his daughter Jean and the breakdown of his family.

Mark Twain’s final years were a stark contrast to his earlier life, filled with the optimism of youth and the drive for adventure. As Twain faced the realities of aging, loss, and betrayal, his once vibrant sense of humor faded, replaced by sorrow and a deep sense of personal failure.

Despite his personal struggles, Twain remained an influential figure, whose sharp social commentary and reflections on human nature continue to resonate with readers. Twain passed away on April 21, 1910, just one day after Halley’s Comet returned, fulfilling his prediction that he would die with the comet.

His death marked the end of an era, but his legacy as one of America’s greatest writers endures. His life, filled with both triumphs and tragedies, left an indelible mark on American literature and culture.

Key People

Mark Twain (Samuel Clemens)

Mark Twain, born Samuel Langhorne Clemens, is the central character in his own life story, reflecting a complex persona shaped by various personal and professional experiences. From a young age, Twain exhibited an intense drive for independence, particularly during his time as a steamboat pilot on the Mississippi River.

His career path, which included roles as a printer, miner, journalist, and eventually a writer, highlighted his restless nature and search for success. Twain’s connection to the Mississippi River, where he found freedom, and his diverse professional background contributed to his unique perspective as an author.

He is often regarded as a symbol of American humor, but his sharp critiques of human nature and societal issues reveal a more serious side. Twain’s sharp wit often masked his deeper emotional struggles, particularly the profound loss he experienced through the deaths of his loved ones, including his wife, Livy, and daughter, Susy.

Despite his fame and public persona, Twain grappled with personal isolation, his complex relationships with his family, and his evolving views on race and human nature. He was a man of contradictions, embodying both humor and deep introspection, and these complexities made him a towering figure in American literature.

Olivia “Livy” Clemens

Livy Clemens, Mark Twain’s wife, played a pivotal role in his life and emotional well-being. Mark Twain’s deep love and devotion to Livy are evident throughout their marriage, and her illness became a major source of emotional turmoil for him in his later years.

Twain’s grief and guilt regarding her declining health and eventual death were profound. He often blamed himself for her suffering, reflecting on their past interactions with a sense of regret.

Livy, a woman of strength and grace, endured immense physical pain, which Twain tried to alleviate by seeking medical help and exploring various treatments. Despite her frailty, Livy’s occasional moments of improvement gave Twain hope, though these were fleeting.

Twain’s anguish over her deteriorating health was compounded by his own physical struggles and the emotional strain of the situation. Livy’s death in 1904 marked the greatest loss in Twain’s life, leaving him devastated and struggling with a sense of void that would never be filled.

Her absence deeply affected him, and her death contributed to his growing emotional isolation in the years that followed.

Orion Clemens

Orion Clemens, Mark Twain’s older brother, had a complex and strained relationship with Sam. While Orion was well-meaning, he lacked the financial acumen and management skills needed to succeed in the business ventures they pursued together.

As a result, Sam grew resentful of Orion, particularly during their time working together in the printing business. Sam’s frustration with his brother’s mismanagement led to a gradual emotional distance, although he maintained a sense of familial loyalty.

Orion’s financial struggles, combined with his inability to provide Sam with the independence he sought, contributed to Sam’s desire to leave Hannibal and explore new opportunities. Despite their differences, Sam’s writing, which was born out of his early experiences, reflects a blend of the influences from both his brother and his upbringing, even as he distanced himself from the constraints that Orion’s life represented.

Clara Clemens

Clara Clemens, the daughter of Mark Twain and Livy, had a complicated relationship with her father in his later years. After Livy’s death, Clara became a source of support for Twain, though their relationship was not without its challenges.

Clara, who had her own emotional burdens, struggled to cope with her mother’s passing and the impact of her father’s personal losses. Twain, who had been distant from Clara in earlier years, relied on her more heavily as his health declined.

Their interactions were marked by a sense of mutual need, as Twain leaned on Clara for emotional support while grappling with his grief and isolation. Clara’s emotional breakdown following Livy’s death added to Twain’s burdens, highlighting the fractured nature of their family in the wake of the loss.

Clara’s role as caretaker and confidante demonstrated her loyalty to her father, even as she struggled to cope with the complexities of their relationship and the family’s collective grief.

Isabel Lyon

Isabel Lyon was Mark Twain’s secretary and confidante in his later years. Twain initially trusted Isabel deeply, even allowing her to play a significant role in his personal and professional life.

However, their relationship took a dramatic turn when Twain discovered that Isabel had been embezzling funds, a betrayal that shattered his trust. Twain’s anger was not only directed at Isabel for her financial misconduct but also for her emotional manipulation, as she had exploited his vanity and self-absorption to gain his trust.

This personal betrayal exacerbated Twain’s growing isolation, and his writings from this period reflect his bitterness and sense of being deceived. Isabel’s relationship with Ralph Ashcroft, who had also worked for Twain, deepened the sense of personal betrayal, as Twain believed Ashcroft had turned Isabel into a thief.

The fallout from this betrayal led to strained relationships within Twain’s family, particularly with his daughter Jean. Twain’s sharp critiques of Isabel and Ashcroft in his writings, including the “Ashcroft-Lyon Manuscript,” revealed the extent of his emotional turmoil and his feeling of being manipulated.

Jean Clemens

Jean Clemens, Mark Twain’s youngest daughter, was a source of deep concern for her father due to her ongoing struggles with epilepsy. Twain’s relationship with Jean was marked by both love and guilt, as he often felt that he had failed to recognize her worth until it was too late.

Jean’s condition weighed heavily on Twain, who, despite his emotional turmoil, tried to provide her with support. However, the increasing challenges of managing her health and emotional well-being placed additional strain on Twain during his final years.

His guilt over his treatment of Jean, combined with the loss of Livy and the turmoil with Isabel Lyon, deepened his sense of regret and sorrow. Jean’s struggles, both physical and emotional, contributed to the sense of isolation and despair that Twain experienced in his final years, underscoring the personal losses that marked his later life.

Ralph Ashcroft

Ralph Ashcroft, a close associate of Isabel Lyon, played a significant role in the emotional unraveling of Mark Twain’s final years. Ashcroft’s involvement in the betrayal of Twain’s trust, particularly through his connection with Isabel, compounded the emotional damage Twain suffered.

Twain’s writings during this period are filled with scorn for Ashcroft, whom he viewed as a manipulator and opportunist. Ashcroft’s role in the financial and personal betrayal of Twain exacerbated the rift between Twain and his family, particularly with his daughter Jean.

The actions of Ashcroft and Isabel Lyon shattered Twain’s sense of security and contributed to his growing emotional isolation, as he struggled to come to terms with the betrayal that fractured his inner circle.

Themes

Personal Growth and the Search for Independence

Mark Twain’s early life, marked by a restless search for independence, is a defining feature of his personal and professional evolution. Born into a family with financial struggles, Twain was propelled by the desire to escape the constraints of his environment and to carve out a life on his own terms.

As a young man, he moved away from his family to work as a printer in different cities, and later ventured west in pursuit of fortune. It was in these early years of struggle, failure, and experimentation that he developed a sense of individuality that would later permeate his writing.

His early experiences working with his brother Orion in the printing business were fraught with tension, but they contributed to his evolving perspective on authority and self-reliance. His time as a silver prospector in Nevada not only helped him financially but also fueled his desire to explore new ideas and engage with a variety of people, which deeply influenced his work as a writer.

Through these journeys, both physical and intellectual, Twain honed his voice and began to identify the aspects of human nature that would shape his literary pursuits, setting the stage for the sharp social commentary that characterized much of his later work.

Humor as a Vehicle for Social Critique

Throughout Mark Twain’s career, humor served not just as entertainment but as a profound method for critiquing societal norms and human behavior. His sharp wit, often laced with satire, became a tool for exposing the absurdities and injustices of his time.

Twain’s humor was deeply connected to his personal experiences, including his observations of the cultural landscape of the Gilded Age. His critical eye was particularly aimed at the contradictions within American society, from the rapid industrialization that led to increased wealth inequality, to the persistent racial prejudices of the time.

Twain’s humor often allowed him to mask deeper critiques of religion, morality, and social conventions. Works such as The War Prayer and Huckleberry Finn illustrate how Twain could employ humor to criticize everything from religious hypocrisy to the institution of slavery.

His ability to blend comedy with commentary made his works both accessible and deeply impactful, inviting readers to laugh while also confronting the uncomfortable truths about the human condition. Twain’s use of humor was not merely for comedic relief but as a lens through which he could explore the dark and complex realities of the world around him.

The Weight of Personal Loss and Grief

The latter part of Mark Twain’s life was marked by profound personal loss, which deeply affected his emotional and psychological state. Twain’s relationship with his wife, Olivia “Livy” Clemens, was a source of great joy, but as her health deteriorated, it became a major source of grief for him.

Twain’s attempts to care for Livy during her long illness highlighted his vulnerability and his inability to control the inevitable course of her condition. The death of their daughter Susy, followed by Livy’s passing, left Twain emotionally devastated.

His grief was compounded by feelings of guilt and regret, as he questioned his role in their suffering. This sense of helplessness was reflected in his strained emotional state and physical health.

Even as Twain struggled with bronchitis and personal health problems, he found solace in his writing, using it as an outlet to process his grief. However, his personal losses took a toll on his humor, as the biting wit he was known for was often overshadowed by a sense of deep sorrow.

His personal pain became a critical part of his later works, including his critiques of life, religion, and society, where the themes of loss and disillusionment were more pronounced. Twain’s reflections on loss and grief were raw and unfiltered, painting a portrait of a man wrestling with his own emotions while trying to maintain his public persona as a humorist.

The Complexity of Relationships and Betrayal

Mark Twain’s personal life was filled with complexities, particularly in his relationships with those closest to him. The betrayal he felt at the hands of Isabel Lyon, his secretary, and Ralph Ashcroft, her accomplice, was one of the most tumultuous episodes in his final years.

Twain, who had trusted Isabel with his personal and financial matters, was devastated to discover that she had been embezzling funds from him. This betrayal was not just financial, but deeply personal, as Twain had allowed Isabel into his private life, even depending on her for emotional support after the death of his wife.

His anger and disillusionment with Isabel and Ashcroft were palpable in his writings, where he portrayed them as scheming and deceitful individuals who had exploited his trust for their gain. This sense of betrayal intensified the emotional strain he was already experiencing from the loss of his wife and daughter.

The breakdown of his relationship with Isabel further isolated Twain, leaving him vulnerable to feelings of abandonment. The conflict with Isabel and Ashcroft underscored the complicated nature of Twain’s relationships, where deep trust was often followed by profound disappointment.

This theme of betrayal, both personal and financial, played a significant role in Twain’s final years, coloring his interactions with those around him and impacting his emotional well-being.

The Struggle with Mortality and Legacy

As Mark Twain’s health began to decline in his later years, he confronted the reality of his mortality in a more profound way. His physical ailments, including his struggles with angina pectoris and bronchitis, were accompanied by a growing sense of disillusionment with the world around him.

His reflections on religion, particularly in works like Letters from the Earth, revealed his skepticism toward the traditional views of God and the afterlife. Twain’s biting critiques of religious institutions and his views on death and the human condition reflected a man who was grappling with his own mortality and questioning the meaning of life.

His humor, once a tool for societal critique, now became an outlet for expressing his despair and bitterness. Twain’s growing sense of isolation was also influenced by the loss of his family members, as well as the collapse of his personal relationships.

The death of his wife and daughter left Twain feeling disconnected from the world, and his health continued to deteriorate, leading him to question his place in the world and the legacy he would leave behind. Despite his public persona as a humorist, Twain’s later years were filled with a profound sense of loss and regret, as he grappled with the impermanence of life and the inevitability of death.

His passing in 1910, just as Halley’s Comet made its return, served as a fitting end to the life of a man whose journey had been marked by both great achievements and deep personal struggles. Twain’s reflections on his own mortality left a lasting impression on his readers, solidifying his legacy as a writer who captured the complexities of the human experience with both humor and sorrow.