Mask of the Deer Woman Summary, Characters and Themes

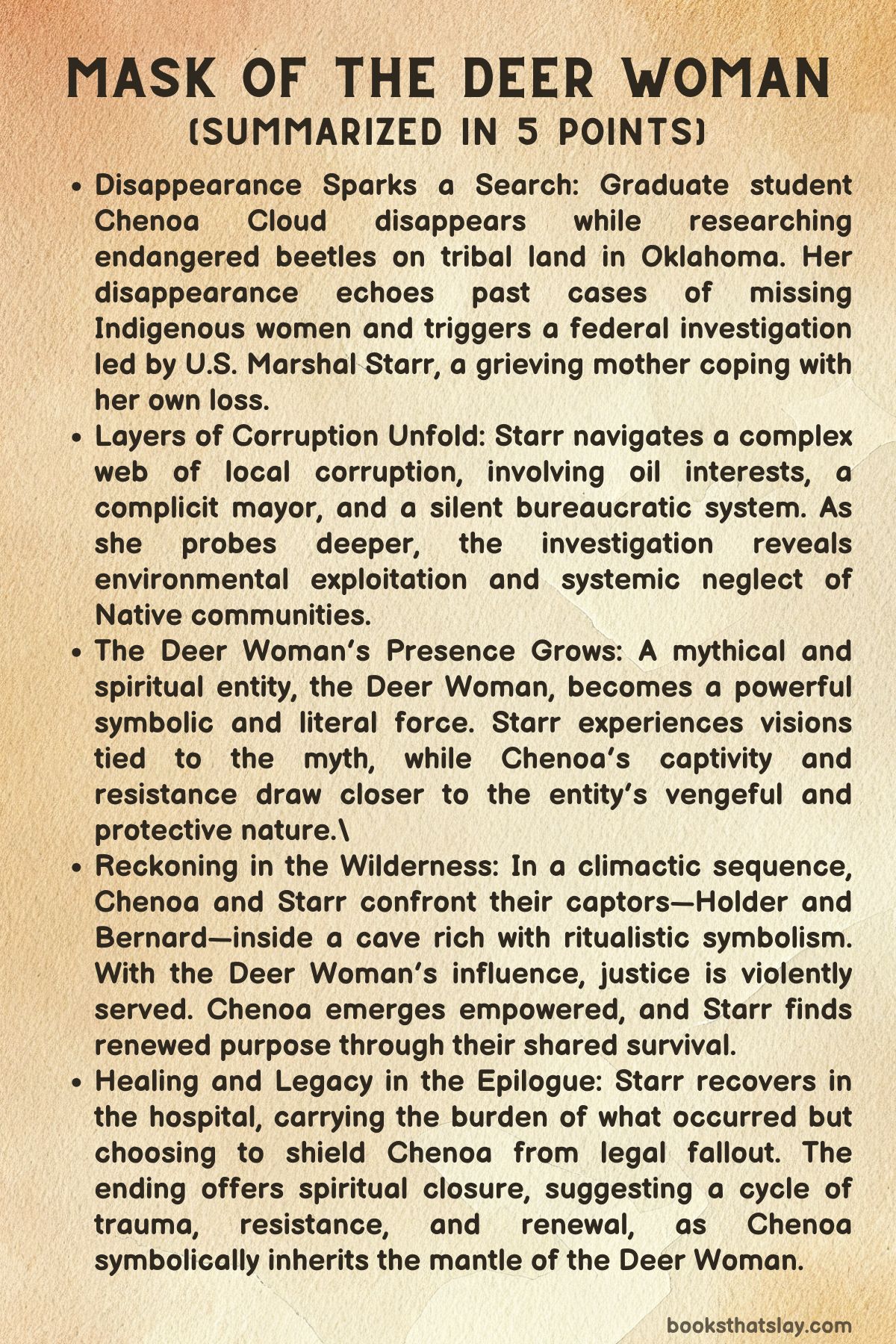

Mask of the Deer Woman by Laurie L Dove is a suspenseful and emotionally intense novel that explores the interconnection between violence against Indigenous women, spiritual tradition, environmental preservation, and personal trauma. Set on the Saliquaw reservation in Oklahoma, it follows tribal marshal Carrie Starr, a former Chicago cop haunted by personal tragedy, as she investigates the disappearance of Chenoa Cloud, a young Indigenous woman researching an endangered beetle that threatens corporate fracking interests.

As the investigation deepens, the story unfolds through layers of myth and reality, asking profound questions about justice, belonging, and the cost of truth in a world shaped by grief and resistance.

Summary

On the Saliquaw reservation in Oklahoma, Chenoa Cloud, a Native graduate student studying the endangered American burying beetle, ventures alone into the wilderness, hoping to gather critical ecological data. Her goal is twofold: secure the protection of the beetle’s habitat through new conservation legislation and halt the oil industry’s encroachment on tribal land.

Her disappearance ignites alarm, especially among her family and those aware of how her work threatens powerful interests. The memory of other missing Native women looms large, and Chenoa’s absence becomes both a personal and political crisis.

Enter Carrie Starr, a weary, traumatized ex-Chicago cop recently appointed as the tribal marshal. Still grieving the loss of her daughter Quinn and exiled from her former life, Starr arrives on the reservation expecting a quiet, detached assignment.

However, she’s pulled into Chenoa’s case by Odeina Cloud, Chenoa’s mother, and soon begins encountering strange and unsettling signs—a mask hanging in a tree, hushed talk of the Deer Woman, and flickers of something not easily explained. Starr initially tries to dismiss these warnings, but as clues mount, she is forced to confront forces both human and mythic.

Meanwhile, Horace-Wayne Holder, a land speculator allied with Blackstream Oil, is determined to push through a fracking deal on land that may harbor endangered species. Holder’s schemes are threatened by Chenoa’s research.

In a world where ecological science collides with Indigenous sovereignty and corporate greed, Chenoa’s knowledge becomes dangerous. Holder’s desire to silence her intertwines with local political maneuverings, including a tribal council meeting where economic promises clash with cultural preservation.

The meeting ends with Blackstream’s proposal being approved, though it reveals a deep schism in the community.

As Starr’s investigation deepens, she crosses paths with Junior Echo, a troubled local man with a painful past and strange tales of a horned doe. Junior’s cryptic recollections, tied to folklore about the Deer Woman—a figure of justice and vengeance—begin to mirror Starr’s own disoriented sense of reality.

The story intensifies when Starr discovers a body near Crawl Canyon, initially mistaken for Chenoa but later identified as Sherry Ann Awiakta, another young woman from the community. The scene is marked by disturbing clues: charred remains, a scorched ring of earth, and an antler placed nearby.

Starr struggles with the trauma this death triggers, especially as it echoes her own experience with Quinn. At Odeina Cloud’s trailer, Lucy Cloud makes an enigmatic comment suggesting Starr once lived among them—a revelation that unsettles her already fragile understanding of identity and memory.

As she attempts to hold the investigation together, Starr finds herself increasingly surrounded by both personal grief and supernatural signs. She battles bureaucratic obstacles, emotional fatigue, and the weight of cultural history that resists rational categorization.

Sherry Ann’s autopsy reveals strange patterns—two different weapons, soil in her mouth, and signs that she was unconscious before being burned. The local power structure begins to show cracks.

Bernard, the seemingly mild-mannered city manager, is shown to be conducting a quiet audit of financial irregularities tied to Mayor Taylor, further complicating the community’s internal tensions.

Starr delivers the death notification to Sherry Ann’s family under harrowing circumstances, swerving off the road to avoid a deer and stumbling into an abandoned house. There, she uncovers what may be more blood evidence.

The investigation becomes increasingly entwined with the past as Chief Byrd shares that his daughter Loxie disappeared years ago under eerily similar conditions. He suspects Junior may hold knowledge about the disappearances, though nothing is proven.

Byrd also reveals his reluctant support of the oil deal as a pragmatic choice for the tribe’s survival.

Starr interrogates Junior further and discovers a hidden shed where he has created a mosaic ceiling from bottle glass—an unexpected haven of beauty and spiritual reflection. This moment shifts Starr’s perception of Junior and deepens the story’s emotional and cultural resonance.

It’s not just a murder mystery but a community struggling to hold onto its humanity amid trauma, neglect, and environmental assault.

The final act is marked by a furious storm, physical peril, and spiritual reckoning. Starr treks into the wilderness alone, following a map drawn by Chenoa that leads her to an area marked “Manitou,” believed to be the beetle colony’s site.

Simultaneously, Holder and Mayor Taylor pursue their own ends. Their alliance shatters when Holder murders the mayor, sensing betrayal.

Meanwhile, Bernard is exposed as a serial killer, having used the reservation’s caves as burial sites for his victims—including Chief Byrd’s daughter and Sherry Ann. Chenoa, held captive by Bernard, is hidden deep in these caves.

Starr finds herself captured and wounded inside the caves, hallucinating or perhaps communing with the Deer Woman. The figure guides her spiritually and physically.

Chenoa, too, draws on the Deer Woman’s spirit and manages to kill Bernard, possibly using supernatural force, as antlers again appear as symbols of justice and transformation. Starr, near death, tells Chenoa to place the blame for Bernard and Holder’s deaths on her, hoping to protect Chenoa and ensure justice is served, even at her own expense.

Starr survives but is left physically and emotionally wrecked. In the hospital, she finds few visitors but gains a quiet sense of clarity.

Watching birds from her window, she begins to understand freedom and belonging differently—not as an escape from the past but as an acceptance of it. With this realization, she leaves the hospital without fanfare, returning to the reservation.

In her Bronco, the ghost or memory of her daughter Quinn appears beside her. Quinn’s presence is not one of horror but of peace, symbolizing that Starr’s path of grief has come full circle.

The novel closes with Starr driving back into the heart of a community she now recognizes as her own. Between the earthly and the spiritual, the real and the mythical, she finds her place—fractured, uncertain, but determined.

Mask of the Deer Woman ends not with tidy resolution but with a vision of resilience born from pain, mystery, and the enduring power of ancestral strength.

Characters

Chenoa Cloud

Chenoa Cloud serves as both the spiritual and narrative catalyst of Mask of The Deer Woman. A young Indigenous woman and graduate student, she represents the confluence of modern scientific pursuit and ancestral reverence.

Her passion for ecological preservation, particularly her quest to locate the endangered American burying beetle, is deeply rooted in both personal redemption and communal responsibility. Chenoa is not merely a researcher; she is a vessel for historical trauma, cultural reclamation, and environmental guardianship.

Her disappearance sets off the central mystery, but even in absence, her presence looms large—as symbol, threat, and hope. The tension between her scientific work and the looming fracking project underscores her role as a disruptor of systemic violence.

Moreover, Chenoa’s connection to the Deer Woman legend, which she ultimately channels in the final act of the story, transforms her into a mythic figure—one who transcends victimhood and asserts ancestral justice. Her emergence from captivity and her decisive actions affirm her evolution from scholar to avenger, offering a redemptive inversion of the “missing woman” narrative.

Carrie Starr

Marshal Carrie Starr is the haunted heart of Mask of The Deer Woman, a woman balancing on the edge of duty, despair, and spiritual reckoning. Once a Chicago police officer undone by personal tragedy and institutional failure, she arrives on the reservation as a reluctant outsider—cynical, traumatized, and armed with a thin veneer of professionalism masking her unresolved grief over her daughter Quinn’s death.

Starr’s investigation into Chenoa’s disappearance and Sherry Ann’s murder becomes not only a procedural effort but also an intensely personal pilgrimage. As she uncovers layers of violence against Indigenous women, her own buried past—her time on the rez as a child, her father’s betrayal, and her feelings of cultural dislocation—resurfaces.

Her eventual vision of the Deer Woman and her ability to act upon spiritual intuition rather than just rational deduction signify her transformation. Starr’s brutal journey through the wilderness, both literal and emotional, brings her to the edge of death, yet also to the cusp of spiritual healing.

By novel’s end, she is not only a law enforcer but a bridge between two worlds: settler and Indigenous, corporeal and spectral, broken and reborn.

Odeina Cloud

Odeina Cloud, Chenoa’s mother, is a quiet force in the novel—a figure of enduring maternal strength, grief, and wisdom. Unlike Starr’s visceral and chaotic emotional expressions, Odeina represents a steady, grief-hardened resolve.

Her urgency in mobilizing Starr to take her daughter’s disappearance seriously speaks to the often-dismissed concerns of Native women when their children go missing. Odeina embodies a generational burden of loss and neglect but channels it into action rather than despair.

Her interactions with Starr also reveal subtle critiques of outsider authority and the limitations of formal justice systems when applied to Indigenous realities. Though she occupies less narrative space, her role is vital—serving as both a mother in mourning and a keeper of memory and truth.

Junior Echo

Junior Echo is one of the novel’s most complex and compelling characters, initially introduced as a drunken, troubled man but slowly revealed as a haunted, grief-stricken individual with deep roots in the community and ties to Starr’s forgotten childhood. His recollection of killing a supernatural deer in his youth and the subsequent belief that he is cursed encapsulates the novel’s central themes of guilt, ancestral consequence, and spiritual reckoning.

Junior’s transformation from a perceived suspect to a figure of empathy unfolds gradually, revealing his artistic soul, manifested in the creation of a luminous bottle-glass ceiling. This act of beauty and reverence positions him as a man capable of redemption and mourning.

Through Junior, the narrative interrogates stereotypes about Indigenous masculinity and alcoholism, offering instead a portrait of quiet grief and misunderstood kindness.

Horace-Wayne Holder

Holder represents the ruthless capitalist engine of the novel, a land speculator whose allegiance to Blackstream Oil makes him the face of environmental and moral degradation. His disdain for the community and willingness to dispose of anyone—especially Chenoa—who threatens his interests exposes the violent lengths corporate interests will go to protect their profits.

Holder’s character lacks the moral ambiguity of others; he is unapologetically self-serving and paranoid, and his eventual murder of Mayor Taylor illustrates his spiral into desperation and power-lust. As a narrative device, Holder functions as a physical embodiment of settler colonialism’s most dangerous impulses—extraction, exploitation, and erasure.

Bernard

Bernard is perhaps the most disturbing character in Mask of The Deer Woman, a seemingly innocuous figure who is ultimately revealed to be a serial killer preying on Indigenous women. His dual role as a city administrator and murderer underscores the horror of bureaucratic indifference disguising predatory intent.

The revelation that he has used the reservation’s caves as a killing ground for years deepens the novel’s commentary on how systemic neglect allows violence to fester unseen. Bernard’s calm demeanor masks an insidious pathology, and his death at Chenoa’s hands is both a triumph of survival and a chilling assertion of vengeance.

He stands as the novel’s darkest commentary on the silent, often invisible menace lurking behind institutional façades.

Mayor Helen Taylor

Mayor Taylor is a secondary but symbolically important character, representing the bureaucratic face of environmental devastation and political corruption. While not as overtly violent as Holder or Bernard, her complicity and willingness to broker destructive deals for personal and political gain reveal the dangers of transactional governance in marginalized communities.

Her ultimate betrayal of Holder and subsequent murder mark her as a failed manipulator, one who underestimates the forces—both human and spiritual—arrayed against her.

Chief Byrd

Chief Byrd is a deeply conflicted figure, straddling the moral tightrope between community loyalty and political pragmatism. Having lost his daughter Loxie to the same epidemic of disappearance and murder afflicting the community, he is a man marked by quiet sorrow.

Yet, his decision to support the oil deal—framed as a desperate bid for economic survival—places him at odds with preservationists like Chenoa and even with his own grief. His character raises difficult questions about leadership under constraint and the compromises Indigenous leaders are often forced to make under the pressures of poverty, legacy, and hope.

Sherry Ann Awiakta

Though her presence is largely posthumous, Sherry Ann Awiakta becomes a powerful symbol in the novel—a stand-in for countless Indigenous women whose lives end in silence and whose deaths go unavenged. Her return to the rez before her murder speaks to a yearning for belonging, and her death—ritualistic, brutal, and covered in silt—catalyzes Starr’s deeper involvement in the case.

Sherry Ann’s body becomes a site of convergence for themes of violence, neglect, and sacred vengeance, making her death a spiritual and political turning point in the narrative.

Shane “Minkey” Minkle

Minkey is a somewhat ambiguous figure, a man sent to assist Starr but whose motivations remain murky. His presence hints at broader networks of interference and misdirection, particularly from municipal powers like Mayor Taylor.

Whether he is an inept bureaucrat or a subtly sinister plant is never entirely clarified, but his character adds to the pervasive atmosphere of distrust, confusion, and hidden agendas that permeate the narrative. He underscores how even those who seem peripheral may play roles in maintaining harmful systems or enabling negligence.

Themes

Violence Against Indigenous Women and Institutional Neglect

The recurring presence of missing and murdered Indigenous women throughout Mask of The Deer Woman forms the story’s most devastating throughline, highlighting both the deeply personal losses suffered by families and the systemic indifference that surrounds their disappearances. Chenoa Cloud’s vanishing sets this pattern into motion, but it’s clear from the beginning that she is not an isolated case.

The novel repeatedly emphasizes that the crisis is widespread and long-running, with names listed like a mournful litany during Chenoa’s trek and cold case files cluttering Starr’s workspace. These are women whose lives were diminished not only by the violence committed against them but by the inadequate investigations, the silence, and the bureaucracy that followed.

The presence of kaolin in the mouths of both Sherry Ann Awiakta and another decade-old victim implies a serial predator preying specifically on Native women, further cementing the reality that these girls are targeted, vulnerable, and unprotected. Carrie Starr’s struggle to pursue these cases while under threat of dismissal encapsulates the bureaucratic failure that compounds the tragedy.

The narrative doesn’t allow readers to look away from the societal and institutional refusal to protect Indigenous women or to value their lives equally. It shows how that refusal reverberates through every character touched by loss—from grieving parents to overworked tribal law enforcement—painting a grim, unresolved portrait of a national epidemic cloaked in political silence and spiritual grief.

Environmental Destruction and Exploitation

Set against the backdrop of Oklahoma’s Saliquaw reservation, the land is not merely a setting in Mask of The Deer Woman—it is a living, threatened character whose fate is entangled with both the survival of the community and the motivations of the novel’s antagonists. The endangered American burying beetle becomes a symbol of fragile resistance, holding the power to stop fracking operations that promise economic revival at the cost of environmental ruin.

Chenoa’s mission to document the beetle colony becomes more than academic; it becomes a quiet act of rebellion against centuries of land theft and corporate exploitation. Her disappearance is directly tied to the threat she poses to the oil deal, and her silencing mirrors the extractionist logic that treats both the land and its people as expendable.

Meanwhile, figures like Holder and Mayor Taylor embody the collusion between corrupt local government and big oil interests, willing to obscure evidence and even murder to advance their financial stakes. The fracking debate—voiced in cacophony at tribal meetings—divides the reservation between those desperate for financial relief and those committed to cultural and ecological preservation.

The beetles, as ancient recyclers of decay, offer metaphorical commentary on the cycles of death and renewal, highlighting how environmental collapse is not a future threat but a current trauma. As Starr ventures into the wilderness, following maps drawn by a missing girl and encountering signs of ecological imbalance, the natural world becomes a battleground for justice, memory, and survival.

Trauma, Grief, and Maternal Loss

Carrie Starr’s character is profoundly shaped by personal trauma—the death of her daughter Quinn looms over every decision, every nightmare, every flash of rage or numbing silence. Her emotional dislocation is paralleled by her physical alienation from both her past and the Saliquaw community she reluctantly joins.

Yet, through her investigation and eventual connection with Odeina Cloud and the mothers of the lost girls, she begins to forge a link not just to her own grief, but to a shared, cultural mourning that deepens the narrative’s emotional resonance. Maternal loss is not exclusive to Starr; it is a collective wound for many characters.

Odeina’s search for Chenoa, Chief Byrd’s quiet sorrow for his missing daughter Loxie, and even Junior’s guilt for the deaths that followed his boyhood encounter with Deer Woman all reflect the wide net of pain cast by generational loss. These characters are not defined solely by their suffering, but they are shaped by it—haunted and motivated in different ways.

Grief in the novel becomes both debilitating and galvanizing, pushing characters toward justice while also threatening to consume them. The spiritual appearances of Quinn and Deer Woman further blur the line between the living and the dead, suggesting that the lost are never truly gone—they linger, as memories, visions, guides, or warnings.

The novel refuses closure and instead examines how mourning can manifest as obsession, hallucination, paralysis, or resistance, making trauma a force that binds characters together across divides of identity, allegiance, and morality.

Cultural Disconnection and Identity

Carrie Starr’s mixed heritage and estrangement from the reservation allow the novel to explore how identity can be a fractured, contested terrain. She is at once insider and outsider, Native and white, victim and enforcer.

Her struggle to belong—mirrored in her constant self-doubt and visible discomfort—acts as a lens for examining the tension between personal identity and communal expectation. Starr’s past, long buried under denial and silence, is reawakened when Lucy Cloud informs her that she once lived with them, cared for by Junior.

This revelation repositions Starr within the community, though not without complexity. Her journey becomes not just a procedural one, but an existential reckoning with heritage, responsibility, and the meaning of home.

Other characters, too, confront questions of cultural disconnection. Junior Echo’s shame and belief in his curse suggest an internalized judgment shaped by old stories and unresolved guilt.

Chenoa, in contrast, represents a newer generation trying to connect science, activism, and ancestral knowledge. Her work with the beetles is deeply tied to place, tradition, and future vision.

The spiritual manifestations—especially Deer Woman—represent a form of cultural return, where myth asserts itself as truth and identity reclaims space in both the physical and psychic realms. This theme underscores how colonization, generational trauma, and poverty have severed people from their roots, and how the path to healing might require both confrontation with the past and embrace of what endures: language, spirit, story, and land.

Justice, Myth, and the Sacred

The tension between justice and vengeance is dramatized through the figure of Deer Woman, a spectral presence that haunts the margins of the novel and eventually emerges as a guiding force in the climax. For Starr, who arrives on the reservation with a Chicago cop’s understanding of justice—evidence, arrest, confession—the shape of accountability is transformed by the rez’s spiritual realities and cultural narratives.

The legal system fails to serve Indigenous communities, and Mask of The Deer Woman shows how justice must often be sought outside its confines. Bernard’s crimes against Indigenous girls go undetected for years despite patterns and clues.

Starr’s own hands are tied by jurisdictional limits and bureaucratic deadlines. But it is Deer Woman—through Chenoa and the land—that delivers ultimate judgment.

The sacred in this novel does not operate at a distance; it intervenes, possesses, transforms. The mask is not just a costume but a conduit, and the antlers are not just symbols but weapons.

This merging of spiritual myth with corporeal reality underscores a worldview where justice can be mystical, where the ancestors speak through animals and symbols, and where the wronged are never without their champions. The cave confrontation, steeped in dread and fever-dream clarity, affirms that some reckonings are beyond human courts.

Chenoa and Starr both become vessels of this sacred reckoning, collapsing the boundaries between victim, protector, and spirit. The final return of Starr to the hospital, her encounter with Quinn’s ghost, and her drive back to the rez signal that justice in this world is not a final act but an ongoing balancing of memory, pain, and belief.