Material World by Ed Conway Summary and Analysis

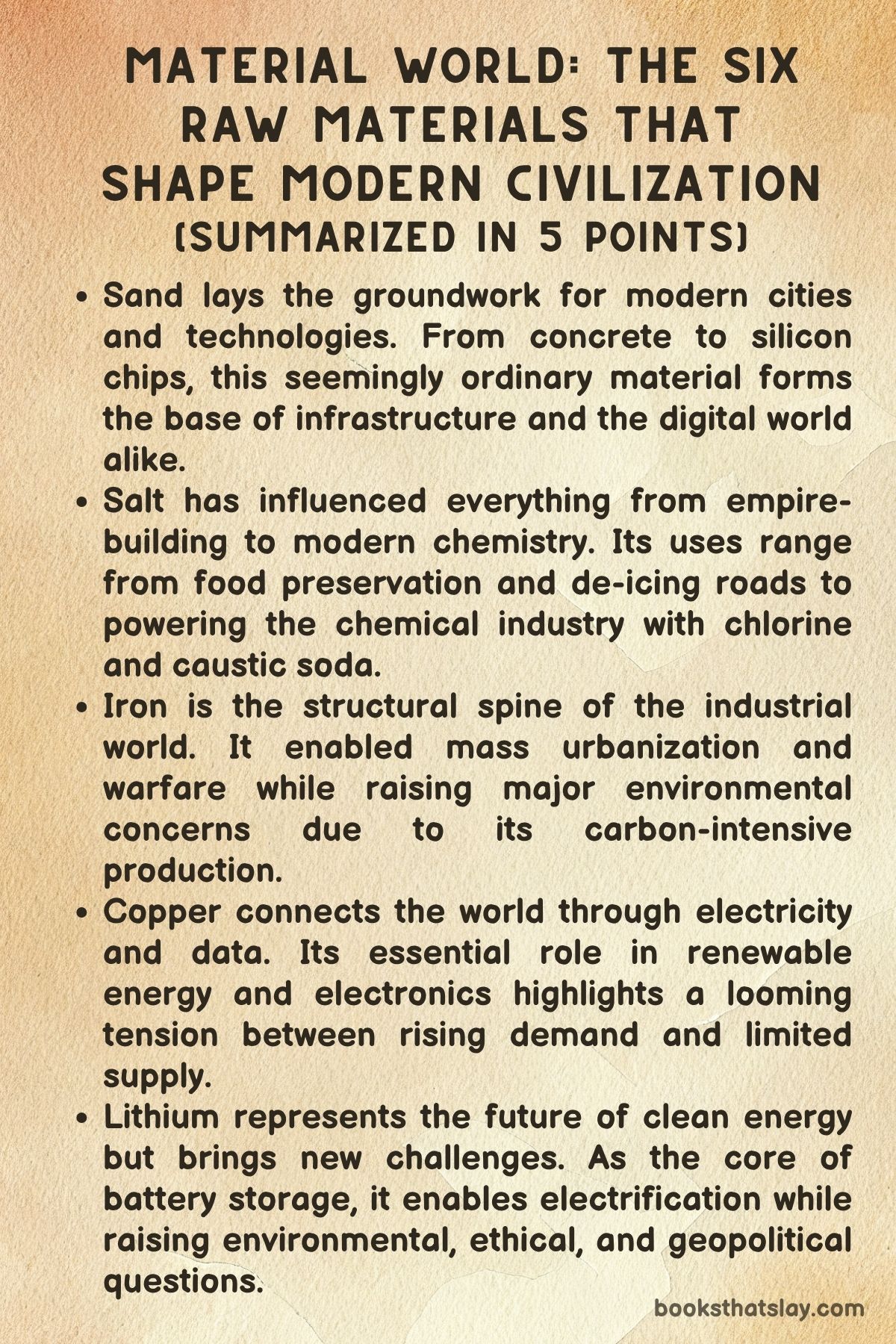

In Material World, Ed Conway explores how six elemental raw materials—sand, salt, iron, copper, oil, and lithium—form the physical and economic bedrock of modern life. While these substances often go unnoticed, they are everywhere: in our homes, technologies, cities, and food systems.

Conway’s approach is grounded in real-world reporting—traveling to mines, factories, salt flats, and oil fields—to show how global supply chains, ecological costs, and geopolitical battles are intimately tied to these substances. The book is a compelling reminder that the modern world isn’t powered only by software or finance, but by tangible matter extracted, moved, and refined on an immense scale.

Summary

The book opens with sand, the most consumed solid material on Earth. Sand might seem trivial, but it is essential for making concrete, glass, and silicon chips.

Conway describes visiting the Great Sand Sea in Egypt, where a meteor strike created Libyan desert glass—an early example of how natural processes can produce incredibly pure silica. From ancient artifacts to skyscrapers, sand’s role has grown dramatically.

Modern cities like Dubai are constructed from concrete that relies on sand, and countries like Singapore import it to expand their territory. However, this high demand has triggered ecological and political issues, including the rise of illegal sand mining that devastates ecosystems and destabilizes river systems.

In tech, sand is transformed into glass for fiber optics and pure silicon for semiconductors. This makes it foundational to the digital age.

Next is salt, a mineral historically central to human health and civilization. Salt was once so valuable it was traded for gold and even used as currency.

Empires taxed it heavily, and rebellions—from the French Revolution to Gandhi’s Salt March—were sparked by control over this essential resource. Salt also revolutionized the chemical industry through electrolysis, producing chlorine and caustic soda used in everything from water purification to PVC and pharmaceuticals.

Despite being cheap today, salt’s industrial relevance is vast—used in de-icing roads, preserving food, and making glass and paper. The section highlights how something chemically simple can be woven into complex systems of health, industry, and state power.

The third material, iron, is the structural heart of civilization. Conway explains how iron and its alloy, steel, have underpinned wars, empires, and modern infrastructure.

The ability to produce steel at scale once defined global power. He takes readers into a blast furnace, describing the intense process of converting iron ore, coke, and limestone into molten steel.

Cities, bridges, cars, and appliances all depend on this process. However, steel production is carbon-intensive, contributing over 7% of global CO₂ emissions.

Conway discusses emerging “green steel” technologies that use hydrogen instead of coal, but notes the cost and scale challenges involved. Still, iron remains central to national identity and development, even as the world transitions to cleaner materials.

Copper is the next focus—less visible than iron, but just as essential. It conducts electricity and heat efficiently, making it the circulatory system of the modern world.

Copper was the first metal humans worked with, and alloying it with tin created bronze, which drove early civilizations. Today, copper is critical for electrification, especially in wind turbines, electric vehicles, and power grids.

But mining copper is extremely resource-intensive, with vast pits dug for small yields. Environmental and social concerns loom large, especially in places like Chile, which supplies nearly a third of global copper.

China’s dominance in refining and supply chains adds another layer of strategic importance. Copper remains a linchpin of both technological advancement and geopolitical maneuvering.

Oil, the fifth material, is both a blessing and a burden. Its discovery and extraction reshaped the 20th century, fueling wars, economies, and entire lifestyles.

Conway illustrates oil’s reach—from gasoline to fertilizers, plastics, and pharmaceuticals. Infrastructure like pipelines and supertankers create a hidden web of supply.

Even as the world embraces renewables, oil remains embedded in supply chains, construction, and manufacturing. Paradoxically, the transition to green tech may increase short-term oil demand.

The environmental damage is significant—oil is a major emitter of greenhouse gases and pollutes ecosystems through spills and refining waste. Yet phasing it out requires a complete overhaul of modern infrastructure and habits.

Finally, lithium emerges as the hopeful but problematic future. It powers rechargeable batteries used in electric vehicles, smartphones, and solar storage systems.

Conway explores its extraction in South America’s salt flats, where brine is evaporated in enormous ponds. This method consumes large amounts of water and impacts local Indigenous communities.

The global race to secure lithium supplies is intensifying, with China controlling much of the refining process. Battery recycling is still in its infancy, and demand is expected to multiply.

Lithium is essential for decarbonization but raises new challenges about resource use, equity, and environmental sustainability. It is the cornerstone of the green revolution, but one that comes with high costs and trade-offs.

In conclusion, Material World underscores a sobering truth. The modern world is not built from code or ideas alone, but from the materials we dig from the ground—each with a story, a cost, and a consequence.

The Six Elements

Sand

Sand emerges as a paradoxical character—omnipresent yet underappreciated. In Material World, Conway presents it as the silent architect of the modern world, shaping cities, technologies, and global trade routes.

Sand’s humble appearance belies its power. It builds skyscrapers through concrete, enables vision and science through glass, and connects continents through fiber-optic cables.

Yet this character is also exploited and endangered. It is hunted by illegal mafias and dredged from coastlines, leaving behind ecological damage.

Sand is presented as both a creator and a victim. It is essential but finite, mundane but magical.

Salt

Salt plays the role of a seasoned elder, deeply intertwined with the history of humanity. It is an ancient, almost mythical figure that has witnessed the rise and fall of empires.

From powering trade routes in the Sahara to sparking revolts against taxation in France and India, salt carries a weight of historical consequence. It is both a literal life-giver—essential for human survival—and a transformative force, catalyzing the birth of the modern chemical industry.

Through Material World, salt becomes a wise, almost spiritual figure. Its influence, though quiet in modern consciousness, remains deeply embedded in every aspect of industrial and biological life.

Iron

Iron is characterized as the rugged, reliable workhorse of civilization. It is a masculine, militaristic figure—strong, powerful, and foundational.

From blacksmiths forging swords to modern blast furnaces pouring molten steel, iron represents both the violence and vitality of progress. Conway’s iron is not just a material but a measure of national strength and industrial sovereignty.

Its journey from war to skyscrapers makes it a symbol of both destruction and development. Iron is also a problematic character in the modern world, emitting vast amounts of CO₂ and struggling to reinvent itself in a green future.

Copper

Copper plays the role of the quiet genius, often overlooked but central to every function. If iron is the bones of modern civilization, copper is its nerves—conducting electricity, enabling communication, and making connectivity possible.

From ancient tools to the arteries of the internet, copper has evolved with humanity. It is always essential but rarely in the spotlight.

Conway portrays copper as a figure under stress. It is demanded by green technology but trapped in an environmentally damaging and geopolitically fraught supply chain.

Like a savant under pressure, copper must now support a booming renewable infrastructure without breaking.

Oil

Oil is the dominant, almost tyrannical character in Conway’s narrative. It is charismatic, addictive, and all-encompassing—at once a life-giver and a destroyer.

Oil fuels economies, powers wars, and lies at the heart of consumer abundance. But it also casts a long, dark shadow: climate change, pollution, and geopolitical instability follow in its wake.

Conway presents oil as a king in decline. Its rule has been absolute for over a century but now faces existential threats from renewable challengers.

Yet, in a cruel twist, the road to a greener world is still paved—at least in the short term—with oil.

Lithium

Lithium is a complex, morally ambiguous protagonist of the future. It is the youngest character in Conway’s cast but perhaps the most consequential.

Lightweight and full of potential, lithium is the key to decarbonization. It enables the battery-powered technologies that promise to reduce our dependence on fossil fuels.

However, this character is also ethically conflicted. Its extraction depletes water sources, displaces Indigenous communities, and raises new forms of imperialism.

Lithium is a reluctant hero, burdened by the expectations of a planet in crisis. It is caught in old extractive patterns and asked to lead a revolution.

Conway treats lithium not as a flawless solution but as a character in a moral quandary. Can it lead us forward without replicating the sins of the past?

Analysis of the Key Themes Explored

Material Foundations of Civilization

At the core of Material World is the assertion that human civilization is materially grounded. Our societal, political, and technological progress is deeply tied to the manipulation of natural substances.

Each of the six materials—sand, salt, iron, copper, oil, and lithium—represents a structural pillar of modern life. These are not passive elements; they are active agents in human advancement.

The book explains how the control, refinement, and application of materials have shaped empires, enabled global commerce, transformed science, and underwritten our modern comforts. For example, the rise of cities was fueled by sand (for concrete and glass), while global dominance in the 20th century depended on oil infrastructure.

Unlike abstract economic theories or digital revolutions, this view insists on physicality. Every byte transmitted, every building erected, every food preserved, every vehicle powered—is possible because of these materials.

Material World is a call to see the invisible. It urges recognition of how everyday items—from the glass of our smartphones to the concrete beneath our feet—are modern extensions of ancient material practices refined at industrial scale.

The author challenges the reader to recognize civilization not just as a web of ideas and systems, but as an accumulation of mined, extracted, and manufactured matter that we rarely acknowledge but entirely depend on.

The Price of Progress

One of the most powerful themes is the cost of modern development—not in currency, but in ecological destruction, human exploitation, and geopolitical tension.

Conway unpacks how progress is often celebrated for what it creates while ignoring what it destroys or displaces. This tension is consistent across all the materials discussed.

The global use of sand for concrete and land reclamation leads to erosion, ecological collapse, and the rise of sand mafias. Lithium extraction, promoted as a green solution, devastates Indigenous lands and depletes scarce water resources in South America.

The steel and oil industries have driven immense economic growth and geopolitical power, but at the expense of staggering CO₂ emissions and toxic waste. This cost is not distributed equally.

Often, the richest societies benefit from the final product, while the poorest regions bear the burdens of extraction and pollution. The author refuses to romanticize innovation without acknowledging the full lifecycle of materials—from origin to obsolescence.

Progress is not a straight line toward improvement but a complex equation of trade-offs, often hidden from public view. This forces the reader to reconsider terms like “sustainability” and “green technology,” which are frequently disconnected from the physical and social consequences of the materials involved.

Resource Control and Power

Material World presents the strategic control of raw materials as a defining force in global power dynamics. Each material has served not only as a resource but as a lever of dominance.

Salt taxes contributed to revolutions. Oil fields fueled wars and redrew borders. Steel production determined industrial superiority.

Today, lithium and copper serve the same function in the emerging energy economy. The control over these resources has increasingly become a matter of national security.

China’s dominance in lithium processing is a modern echo of British coal supremacy or American oil dominance in the 20th century. The United States’ effort to reshore supply chains reflects awareness of material vulnerability.

Throughout history, the ability to control a material supply chain has translated directly into political leverage. Whether it be Rome’s grip on salt roads or the U.S.’s postwar oil power, resources shape global affairs.

The geopolitics of materials are subtle but deeply consequential. Resources are not merely economic inputs—they are geopolitical instruments whose accessibility can determine the fate of entire regions.

Environmental Contradictions of Green Technology

A particularly compelling theme is the paradox embedded in the transition to green technology. While lithium, copper, and rare earth metals are hailed as saviors for the climate crisis, their extraction and refinement often perpetuate environmental degradation.

Solar panels, wind turbines, and EVs require vast amounts of copper and lithium. These must be mined through processes that consume energy, destroy ecosystems, and displace communities.

To build a decarbonized world, we may need to double down on extractive industries—at least in the short term. This contradiction raises a moral question.

Can we solve a crisis of overconsumption by consuming differently, or are we simply shifting the burden? The book suggests that a green revolution without reform of material systems is an illusion.

Even battery recycling is unequipped to deal with the coming flood of lithium-ion waste. This theme critiques techno-optimism and urges a holistic perspective.

Decarbonization is not just a technical challenge but a material one. Solving it will require confronting uncomfortable truths about energy, inequality, and the limits of substitution.

Invisibility of Everyday Infrastructure

One of the strengths of Material World is its effort to highlight how the most important materials in our lives are largely invisible.

Despite shaping everything from skyscrapers to smartphones, materials like sand and copper rarely feature in policy debates, education, or media. The infrastructures of modernity are so well-hidden that people assume their presence without ever questioning their origin.

Roads are made of oil derivatives. Water flows through copper pipes. Salt keeps winter streets passable. These facts are so embedded in daily life that they become invisible.

This invisibility is not accidental. It is rooted in economic abstraction, corporate secrecy, and public disinterest.

Societies often overlook supply vulnerabilities until disruption strikes. Conway pushes readers to become materially literate.

The future will belong to those who understand not just software and systems, but substance. Civilization is not built on code or capital alone, but on atoms processed at scale.